9 Nausea and vomiting

Case

A 21-year-old university student consults because of episodic nausea and vomiting. In between attacks, he is well. However, approximately every 2 months he will experience worsening nausea preceding violent vomiting episodes that can last for 3–5 days. The vomiting has been so severe that he has presented to casualty where intravenous injections of antiemetics have been given. There is mild abdominal pain associated with the nausea and vomiting at times. His bowel habit has been normal. He denies any neurological symptoms. He has had a history of occasional migraine-type headaches, but has otherwise been in excellent health. He has not been taking any regular medications. He has already seen a gastroenterologist who performed an upper endoscopy that was normal and a small bowel x-ray that was normal. Screening blood tests (including electrolytes, liver function tests and a blood count) have all been normal.

Physiology of Vomiting

With the onset of nausea, there will be accompanying autonomic discharge of variable severity. This results in intense salivation, bradycardia, sweating, pallor and hypotension. The normal electrical activity of the stomach may become slow, fast or fluctuate wildly with nausea. It is unclear whether the same neural pathways that mediate vomiting also mediate nausea.

History

Nausea and vomiting are non-specific symptoms and may occur in many diseases. Box 9.1 lists the important causes of nausea and vomiting. When taking the targeted history, it is key to differentiate between vomiting, regurgitation and rumination.

The character of the vomit is useful to document. Undigested food in the vomit may occur from oesophageal disorders (e.g. achalasia or Zenker’s diverticulum). Gastric outlet obstruction may result in partially digested food, free of bile. In small bowel obstruction, the vomitus is usually bile stained. Faecal vomiting indicates distal small bowel obstruction or a gastrocolonic fistula.

The presence of other gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain or diarrhoea suggests a primary gastrointestinal disease. In the presence of significant weight loss with nausea and vomiting, consideration needs to be given to a gastrointestinal tract malignancy, intestinal obstruction or an eating disorder. An adolescent female with a history of repeated bouts of vomiting immediately after meals, particularly after binge eating, may have anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa; accompanying weight loss, fear of gaining weight, impaired body image, amenorrhoea and binge eating should be asked about. The vomiting is generally self-induced; laxatives, diuretics and vigorous exercise may also be used to prevent weight gain (Ch 17).

Investigation

Investigation is undertaken to:

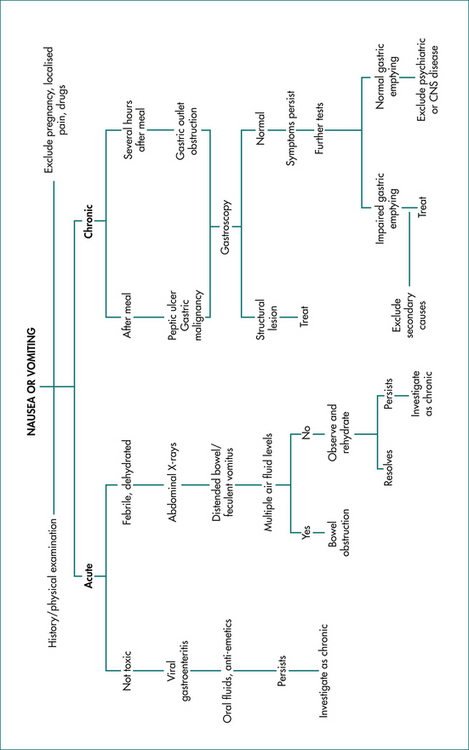

A suggested management algorithm for chronic nausea and vomiting is shown in Figure 9.1. Supine and upright abdominal x-rays will document small bowel obstruction, although in 20% of cases partial small bowel obstruction can be missed with plain films. Upper endoscopy will exclude gastric outlet obstruction and significant gastroduodenal disease, such as peptic ulcer. If small-bowel follow-through fails to reveal evidence of obstruction, which can occur with a partial lesion, an enteroclysis (where barium and methylcellulose are infused into the proximal intestine via a nasojejunal tube in order to provide double-contrast pictures) or computed tomography enterography can be useful. If there is any suggestion of lower bowel obstruction, barium enema or colonoscopy should be undertaken.

Consequences of Nausea and Vomiting

Chronic nausea and vomiting significantly impair quality of life, and warrants appropriate therapy.

Important Diseases that may cause Nausea and Vomiting

Gastric and intestinal obstruction

The nature of vomiting and associated symptoms caused by intestinal obstruction depends on the level of the gut involved as well as the rapidity with which the obstruction occurs (Ch 4). Acute small bowel obstruction is more likely to be associated with severe pain compared with obstruction of a more insidious onset. Bile is almost always present in the vomitus when the obstruction is below the duodenal ampulla. The vomiting of partially digested food one to several hours after eating would suggest obstruction at the pylorus. Malignant obstruction of any form is usually accompanied by anorexia and weight loss. Complete obstruction of the stomach or duodenum usually results in the loss of large volumes of fluid in the vomitus (Ch 4).

Physical examination of the abdomen varies depending upon the cause of the obstruction. In pyloric obstruction, upper abdominal distension and a succussion splash may be observed. Generalised abdominal discomfort may be noted. Distended loops of bowel are observed with peristaltic rushes early in intestinal obstruction, but absent bowel sounds are noted later.

Infection

Acute viral gastroenteritis may result in vomiting. Bacterial gastroenteritis induces vomiting usually accompanied by fever and diarrhoea (see Ch 13). Nausea and vomiting, which occasionally may be prolonged and result in dehydration, may be prominent characteristics of acute viral hepatitis (Ch 24).

Psychiatric disease

Nausea and vomiting are prominent symptoms in eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (Ch 17). Panic attacks can also cause nausea. If nausea is not accompanied by anorexia or is associated with weight gain, an organic cause is rarely observed.

Conditioned reflexes

An offensive sight (e.g. blood) or unpleasant smell may result in immediate nausea and sometimes vomiting in susceptible people. Conditioning may occur in response to such sights or smells, so that nausea and vomiting is more easily precipitated by the same circumstances in the future. Such conditioning also applies to motion sickness and the vomiting induced by chemotherapy.

Principles of Treatment

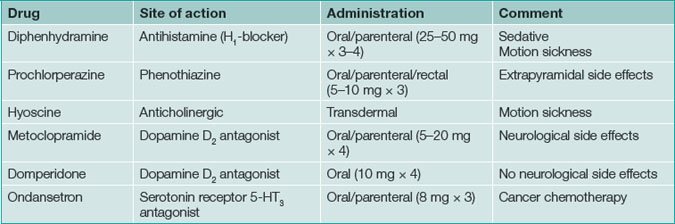

Dietary modification is particularly important if there is evidence of gastroparesis. Frequent small meals (six per day), a low-fat diet, avoidance of indigestible material to reduce the chance of bezoar formation and reduced fibre intake can all be useful. Splitting the ingestion of liquids and solids may reduce symptoms. Liquids are generally tolerated better than solids in this setting, and so the use of a blender or liquid formulas can be helpful. Medical therapy (Table 9.1) may be necessary.

Medical therapy

Prokinetic agents

Metoclopramide (5–20 mg four times a day) is a substituted benzamide, and is a dopamine D2-receptor antagonist. It has central antidopaminergic effects and stimulates cholinergic actions locally in the gut. It is associated with side effects including drowsiness, dystonia, parkinsonism and, rarely, cardiac arrhythmias or tardive dyskinesia (which can be irreversible despite ceasing the medication, particularly in the elderly). Metoclopramide is available both orally and parenterally. Domperidone is another substituted benzamide that poorly penetrates the central nervous system and so has fewer central side effects. It can cause cardiac arrhythmias and gynaecomastia (5%).

Specific Clinical Scenarios

Functional vomiting

This is a rare condition that has been defined by the Rome Foundation Committee (Box 9.2). If gastric emptying is delayed, it is important to exclude chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction as well as mechanical intestinal obstruction. No medications have established efficacy in this group, but anecdotally, tricyclic antidepressants seem to be of value and can be tried at a low dose, but may require full dose to be efficacious.

Key Points

Abell T.L., Bernstein R.K., Cutts T., et al. Treatment of gastroparesis: a multidisciplinary clinical review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:263-283.

Bai Y., Xu M.J., Yang X., et al. A systematic review on intrapyloric botulinum toxin injection for gastroparesis. Digestion. 2010;81(1):27-34.

Ma J., Rayner C.K., Jones K.L., et al. Diabetic gastroparesis: diagnosis and management. Drugs. 2009;69(8):971-986.

Parkman H.P., Camilleri M., Farrugia G., et al. Gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia: excerpts from the AGA/ANMS meeting. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(2):113-133.

Quigley E.M.M., Hasler W.L., Parkman H.P. AGA technical review on nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:263-286.

Soffer E., Abell T., Lin Z., et al. Review article: gastric electrical stimulation for gastroparesis—physiological foundations, technical aspects and clinical implications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(7):681-694.