Chapter 15 Nasal Reconstruction

INTRODUCTION

The nose occupies a prominent position of visual attention in the central face. When examining a face, observers spend a large amount of gaze time on the eyes and on the nose.1 The visual scrutiny of the nose emphasizes the obvious need to offer nasal reconstructive procedures that do more than simply “fill a hole.” The normal nose is a pyramidal structure with its apex in the glabella and its broad, freely mobile base between the eyes and mouth. Although anchored proximally to the face through rigid bony connections, at its distal aspects, the nose is a malleable soft tissue construct comprised of mucosa, cartilage, muscle, subcutaneous tissue, and skin. The underlying architectural support for the distal nose is characterized by an interconnecting arrangement of flat and curved cartilages, and the particular size and shape of these cartilages is what is chiefly responsible for the wide diversity of noses that can still be appreciated as “normal.” When skin is draped over the underlying bony and cartilaginous framework of the nose, a visually complicated facial feature begins to emerge.

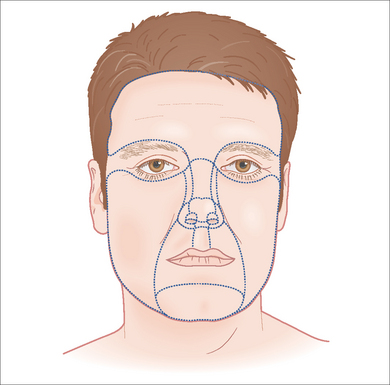

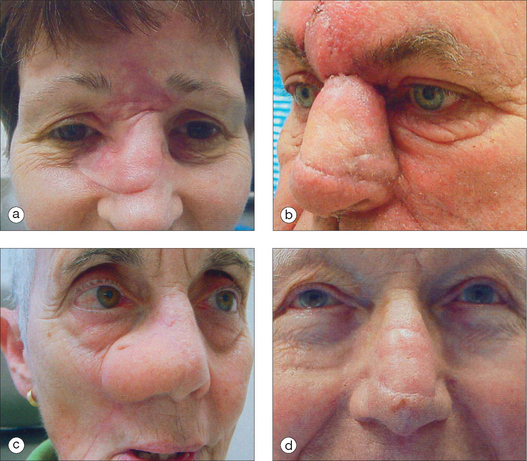

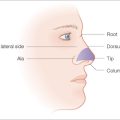

To succeed in nasal reconstruction, the surgeon must first realize how the various visually distinct areas of the nose contribute to the nose’s overall appearance. In general, the face can be divided into aesthetic units, areas in which the skin has its own unique color, texture, porosity, and surface contour. On the face, these aesthetic units are often broad areas of tissue bounded by naturally occurring landmarks. For example, the forehead, as defined by the anterior hairline, the brows, and the bilateral zygomatic arches, is a single visual unit. On the nose, however, the arrangement of aesthetic units becomes much more complicated. Although on casual inspection the nose might seem to represent a single large feature, the nose is much more properly conceived to represent an intricate arrangement of concave and convex surfaces separated by predictable ridges and valleys. These aesthetic units of the nose are exactly symmetrical, and any surgical introduction of asymmetry has dramatic influence on the nose’s final appearance. The division of the nose into aesthetic subunits (Figure 15.1) has great relevance in the success of all nasal repairs. Surgical procedures that attempt to recreate the proper nasal topography and strive to place incision lines along naturally occurring boundaries are generally much more aesthetically successful than procedures that simply cover a wound without attention suitably placed on the aesthetic subtleties that define the normal nose’s topography2 (Figures 15.2, 15.3, and 15.4).

In addition to realizing that the nose is a facial feature with great topographic visual complexity, the dermatologic surgeon should also understand that the nose, in distinction to many other areas of the face, has areas in which the thickness, malleability, and sebaceous gland density of the skin varies tremendously. The nose is typically divided into areas in which the skin is thin, loose, forgiving, compliant, and relatively less sebaceous (the areas of the dorsum, sidewalls, soft triangles, and columella) and areas in which the skin is more adherent, less flexible, thicker, and more sebaceous (the areas of the nasal supratip, tip, and alae).3 Unfortunately, the distribution of these varying skin types (Figure 15.5) is not nearly as predictable as the arrangement of the nasal aesthetic subunits, and the surgeon therefore needs to assess the locations of these varying skin types prior to designing an operative procedure, as thick, sebaceous skin can have a great tendency to distort alar symmetry as it is moved distally. Additionally, if deeper distal defects are filled with the thinner skin of the proximal nose, volume replenishment will not be sufficient, and the important contours of the nose will not be appropriately restored.

After critically assessing the nose’s normal topography and tissue availability, the physician should then be well prepared to begin conceptualizing nasal reconstructive procedures. Nasal wounds can vary tremendously in size, depth, and location. Extensive nasal wounds should be approached with great caution, as the deeper architectural support elements of the nose serve to protect the nose’s important roles in olfaction, phonation, and respiration. If full-thickness nasal wounds are produced upon tumor removal, the complexity of the operative procedures required to repair the wound dramatically increases because internal nasal lining, rigid structural support, and aesthetically proper skin coverage must all be supplied in order to functionally and aesthetically reconstruct the nose. Prior to placing any consideration on the aesthetic coverage of nasal wounds, the surgeon should be prepared to address the functional losses that tumor extirpation might have introduced. The nose must have protected patency for proper functioning, and the distal nasal margins must therefore be appropriately braced with rigid cartilage grafts if the depth of tumor excision has been great enough to produce alar flaccidity (Figure 15.6). If the rigidity of the ala is not restored prior to covering the wound, the weight of any flap will simply exacerbate the alar collapse, and the inevitable contraction that accompanies any wound healing will add further distortion to the unsupported alar margin as the flap matures.

Following adequate tumor removal, repair alternatives are considered based on the size, complexity, and location of the surgical wound. The proper selection of nasal reconstructive techniques begins, then, with an assessment of the wound’s characteristics. One of the most important variables in categorizing the nasal wound is the wound’s location. In the shadowed areas of the alar grooves and the medial canthus, select wounds can be allowed to heal by second intention (Figure 15.7). In general, wounds amenable to second intention healing are small (less that 1 cm in diameter), shallow, located within concave areas, and located at a significant distance (0.5 cm or greater) from the mobile alar margin.4 In other areas of the nose (particularly in convex areas), the selection of second intention healing as a wound management strategy often produces anatomic distortion, contour irregularities, and aesthetically inferior scars (Figure 15.8). If the nasal wound is not located within shadowed alar groove or medial canthus, it is likely not ideally suited for healing by second intention (unless the wound is very small). To begin selecting a nasal repair alternative, the location of the wound should be noted in reference to the quality and availability of the surrounding skin. On the proximal nasal dorsum and sidewalls, there is often sufficient laxity to allow primary closure of small wounds. Because of the compliance of the relatively nonsebaceous skin in these areas, small local flaps can also be created from adjacent tissues. If wounds located along the proximal nasal dorsum or sidewalls are broader, skin grafts can occasionally be useful. Although in general skin grafts are poor aesthetic matches for nasal skin, the relatively nonsebaceous skin of the more proximal nose is better suited for a graft repair than the sebaceous skin of the nasal alae and tip.

Distal nasal wounds offer significant reconstructive challenges. The distal skin of the nose is thick and sebaceous, and wounds in such skin are very difficult to manage without relying upon more complicated reconstructive techniques. Second intention healing of full-thickness wounds over the thickly skinned areas of convexity on the distal nose produces scars that are rarely cosmetically acceptable. Skin grafts, when used to repair defects on the thick sebaceous skin of the nasal tip, often appear relatively shiny and slick, and the grafts commonly fail to offer sufficient volume replenishment (Figure 15.9). For that reason, wounds in distal, thickly skinned areas of the nose frequently demand flap repairs to restore the nose’s delicate contour. Often, distal nasal wounds can be repaired with flaps harvested from the looser, more available nasal skin located immediately proximal to the wound. This allows the unique skin of the nose to be appropriately rearranged. If, however, the surgical wound on the nose is too large to cover with donated skin from the areas of remaining nasal skin proximal to the wound, flaps from the adjacent forehead or cheek can be designed.

The size of the surgical wound also has important ramifications on the success of any nasal reconstructive procedure. As mentioned, small partial-thickness nasal wounds can occasionally be allowed to simply granulate. Wounds up to 1 cm in diameter can often be closed primarily, even when the wounds are located in difficult areas such as the nasal tip (provided there is sufficient adjacent tissue laxity). More complicated wounds understandably require larger reconstructive efforts. If the large wound is shallow (soft tissue remains in the wound’s bed), a skin graft is occasionally the most proper repair alternative. If the larger nasal wound has significant depth (to the subcutaneous tissue or to the underlying cartilage or bone), a flap repair is usually a more palatable reconstructive alternative. Regardless of the size of the wound, the wound should be examined from the aesthetic subunit perspective. If the wound already involves a significant proportion of any aesthetic subunit of the nose, consideration should be given to expanding the wound (sacrificing adjacent normal skin) until the aesthetic subunit boundaries are encountered.2 Doing so will favorably place the incision lines in areas of lowest cosmetic burden.

After the surgical wound has been adequately characterized, repair alternatives can be considered. No surgical reconstructive procedure should be contemplated before an absolute determination of the adequacy of tumor removal, as persistent tumor buried under a graft or flap may be clinically unrecognizable for several disastrous years. The Mohs micrographic surgical technique offers unrivaled success in the treatment of many cutaneous tumors5 and has important tissue conservation abilities.6 For that reason, many primary and recurrent/persistent nasal tumors are ideally excised with the Mohs technique before the resulting wounds are repaired.

RECONSTRUCTIVE OPTIONS

Primary Closure

The layered linear repair (primary closure) is occasionally an ideal reconstructive solution for smaller nasal wounds located along the nasal sidewalls, within the alar groove, or directly centered on the nasal tip (Figure 15.10). All linear closures have wound closure tensions oriented perpendicularly to the long axis of the wound, and on the nose, these wound closure tensions can introduce dramatic nasal asymmetry if broader nasal wounds are selected for closure, particularly on thickly skinned sebaceous noses with little tissue laxity. For that reason, only small (<1 cm) and shallow (no disruption of the underlying architectural framework of the nose) wounds are appropriately selected for primary closure.

Along the proximal nasal sidewalls, a properly oriented linear closure will point toward the medial canthus, as the relaxed skin tension lines in this area are obliquely oriented. If wounds greater than 1 cm in diameter along the proximal sidewalls are closed linearly, however, the obliquely oriented wound closure tensions will typically result in an undesirable ipsilateral alar elevation. In the area of the central nasal tip, small wounds can be directly closed in a vertically oriented linear manner.7 In order to prevent the introduction of very distracting alar asymmetry, the surgical defect should be located in the midline. Before excising the dog-ear redundancies that accompany the linear closure of any circular defect, the surgeon should make certain that the thick, adherent skin of the distal nose has sufficient laxity to allow closure of the distal nasal wound under minimal wound closure tensions. If the wound is closed under inappropriately elevated tension, wound edge ischemia (and the resulting unaesthetic scarring) will result. If wound closure tensions are too high, significant deformity of the nasal dorsum will also be apparent on a profile view. These elevated wound closure tensions will result in an anatomically incorrect indentation, often in the area of the nasal supratip. Higher wound closure tensions also produce an artificial “flared” appearance to the nasal alae. If the degree of alar lift associated with the vertical closure of nasal tip wounds is minor and symmetric, the cosmetic penalty will be small. Greater degrees of alar distortion can produce an acutely angled, sharp, “beak-like” distal nasal deformity.

When performing any linear closure on the nose, care should be taken to avoid producing dog-ear redundancies at the ends of the elliptical closure, as the shadowing that such redundancies produce can be particularly distracting on the nose. For that reason, the length-to-width ratio of linear closures on the nose should be at least 4:1.7 After the dog-ear redundancies adjacent to the wound are excised, the wound is widely undermined in the plane immediately above the paired nasal cartilages. Wide and deep undermining is required in order to minimize wound closure tensions, and the wound should be subsequently closed in a layered manner in order to produce a less apparent scar. Wound edge eversion is particularly important on the distal nose, where the bulky sebaceous lobules tend to produce invagination of the wound’s edges. Meticulously placed subcutaneous-buried vertical mattress sutures help achieve wound edge eversion and displace tension from the wound edges.

Skin Grafts

Because there is a general lack of abundant available donor tissue on the nose, the temptation to cover many nasal wounds with skin grafts can be quite high. Skin grafting techniques, described in greater detail elsewhere in this text, are certainly inherently less complicated endeavors than the design and execution of many nasal flaps, where tissue motion and wound tensions need to be predicted very accurately if anatomic distortion is to be avoided. To be certain, skin grafts have an important role in the reconstruction of select nasal defects. In general, though, the grafts’ inabilities to offer significant volume replenishment limit their utility to exquisitely shallow nasal wounds (Figure 15.9). Skin grafts are also more unpredictable in their eventual aesthetic outcomes than properly executed flaps, and grafts that do not share similar color and texture characteristics with the surrounding nasal skin are typically quite noticeable.

Not surprisingly, skin grafts are less apparent on the thinner, less sebaceous skin of the nose. As such, skin grafts are acceptable reconstructive options for relatively shallow wounds located in the thinned skin zones of the columella and soft triangles and along the nasal dorsum and sidewalls (where greater tissue abundance typically allows more appropriate flap repair options). If appropriately matched donor skin can be identified, skin grafts can be a viable repair option for small and shallow wounds even in the more sebaceous areas of the nasal alae and tip (Figures 15.11 and 15.12). Since the potential textural mismatch of a skin graft when applied to such thicker nasal skin is often glaringly apparent, judicious selection of donor skin is advised. To minimize the size of the skin graft, Burow’s grafts (where the superior portion of the nasal wound is closed in a linear manner and the redundancy removed upon closure of this area is donated to the distal aspect of the wound as a full-thickness skin graft) are also occasionally useful8 (Figure 15.13). Because of potential textural mismatches and because of skin grafts’ limited ability to offer sufficient volume replenishment for deeper nasal wounds, flaps are generally superior reconstructive options for a considerable number of significant nasal defects.

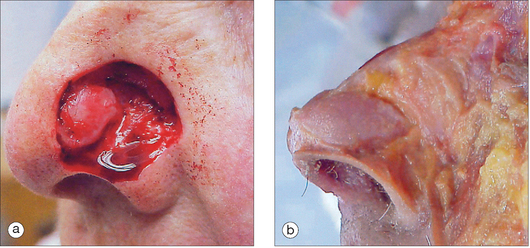

Donor sites for full-thickness skin grafts used in nasal reconstruction could possibly include any hairless area of skin. An ideal skin graft site would offer skin of color, texture, and thickness similar to that of the nose. Additionally, the desirable skin graft donor site would be located in an area of low aesthetic attention. Common donor sites for skin grafts used in nasal reconstruction include the preauricular cheek, the postauricular sulcus, the clavicular area of the chest, and, perhaps most importantly, the concha. All skin graft donor sites have advantages and disadvantages. Preauricular grafts have been historically championed as ideal nasal repair options since the donor area is easily accessible and has been sun exposed. Unfortunately, preauricular skin is generally thinner and much less sebaceous than the skin of the nasal tip and alae. Despite expert surgical technique, scars at preauricular donor sites can also occasionally be visible, and some degree of facial asymmetry can also be introduced. Additionally, in male patients, the harvesting of skin grafts from the preauricular area moves hair bearing skin much closer to the ear, and the tragus can be frustratingly cut during shaving. Postauricular skin can be used as a skin graft donor site, but the photo-protected, less sebaceous skin in this area is uncommonly an ideal match for the exposed, thick, sebaceous skin of the nose. Skin of the supraclavicular chest can be useful for larger wounds on the nose, but this skin’s quality is particularly variable. In some patients, this skin is quite atrophic and inappropriate for the repair of nasal wounds, and in some patients, the thick dermis of the skin in this area makes grafting challenging. Skin grafts harvested from this area also demonstrate a common tendency to heal with distracting pigmentary changes. For these reasons, the skin of the conchal bowl is often an ideal site for the harvesting of skin grafts used in nasal repairs. Because the skin of the concha has been shown to have sebaceous lobules with densities and sizes similar to the thicker skin of the distal nose,9 this skin offers superior donor opportunities. Conchal grafts of up to 2 cm in diameter can be quickly harvested from the cavum and cymba concha, and the perichondrium underlying the skin can be retained in order to offer thicker grafts that nonetheless routinely survive. The donor site of the conchal graft is allowed to heal by second intention, and the cartilage is routinely perforated in order to allow the postauricular skin to more easily cover the exposed conchal cartilage. Such manipulation of the conchal cartilage, though traditionally feared to increase the likelihood of potentially disastrous infectious chondritis, has not been shown to increase the probabilities of concerning postoperative complications.10

Regardless of the graft’s donor site, the success of skin grafting techniques actually depends more on the qualities of the recipient bed than on the characteristics of the donor tissue. Recipient sites that have predictably poor perfusion (because of the patient’s exposed cartilage or bone, associated vascular disease, tobacco abuse,11 previous radiation therapy, anemia, or a host of other concomitant medical issues) rarely promote ideal graft results. Even if the graft survives, the relatively poor initial perfusion rarely allows the graft to offer an ideal aesthetic repair. Despite the inherently poor perfusion of cartilage, small, thin cartilage batten grafts can be used to support the alar margin prior to covering the exposed wound with a skin graft if care is taken to appropriately tack the skin graft around the cartilage graft and to ensure that the majority of the graft is in direct contact with a well-perfused wound bed.3 Cartilage batten grafts should be occasionally taped and thinned superiorly to minimize the risk of a noticeable contour drop-off at the edge of the underlying cartilage graft. Care should be taken to debride the recipient site of any detritus (including electrocautery char), and the graft should be secured with peripheral and basting sutures. Because tie-over bolster sutures have been shown to offer no significant benefit to smaller grafts,12 they are not typically required for the relatively small grafts used in nasal repair.

In addition to split- and full-thickness skin grafts, composite grafts are occasionally useful in nasal reconstruction. Composite grafts are grafts that contain an element other than skin and subcutaneous tissue. On the nose, the most commonly utilized composite grafts are cartilage-containing grafts harvested from various donor sites on the ear. Although composite grafts have opportunities to restore contour to deeper surgical wounds, particularly along the alar rim (Figure 15.14), composite grafts are often less desirable reconstructive options than suitably designed flaps. The harvesting of inherently thick composite grafts can cause aesthetic concerns at the donor site, and the presence of cartilage within the grafts increase the grafts’ metabolic demands, and therefore their failure rates. In addition, composite grafts can be subject to significant shrinkage in the later postoperative period, and it is not uncommon for composite grafts along the alar margin to heal with noticeable “notch” deformities.

Flap Reconstruction of the Nose

Cutaneous flaps offer multiple advantages in the reconstruction of nasal wounds. When properly designed and executed, flaps are safe and predictable reconstructive options for wounds that should not be allowed to heal by second intention or cannot be closed in a simpler linear manner. In distinction to skin grafts, cutaneous flaps offer the ability to cover deep and complicated nasal wounds with tissue that has a similar color, texture, and thickness to the adjacent nasal skin. Because the perfusion of a well-designed flap is protected, the survival rates of flaps typically exceed the survival rates of both split- and full-thickness skin grafts.13 The protected perfusion of a flap also allows the survival of integrated reconstructive elements such as autologous cartilage grafts.

Despite their impressive utility, cutaneous flaps do possess several distinct disadvantages. The geometric design of nasal flaps demands an intricate knowledge of the biomechanical properties of skin and the principles of tissue movement. Flaps created without attention to proper design have great ability to introduce nasal distortion that can be difficult (and frequently impossible) to correct. Additionally, the creation of nasal flaps demands the introduction of occasionally long incision lines on the face, and unless expert surgical technique is utilized, the aesthetic appearance of the flap’s lengthy scars can be distracting. Finally, because nasal flaps frequently require large amounts of undermining, the potential for introducing surgical morbidity is greater than with simpler reconstructive alternatives.

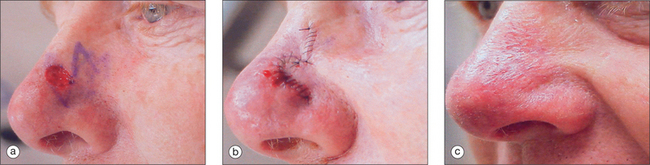

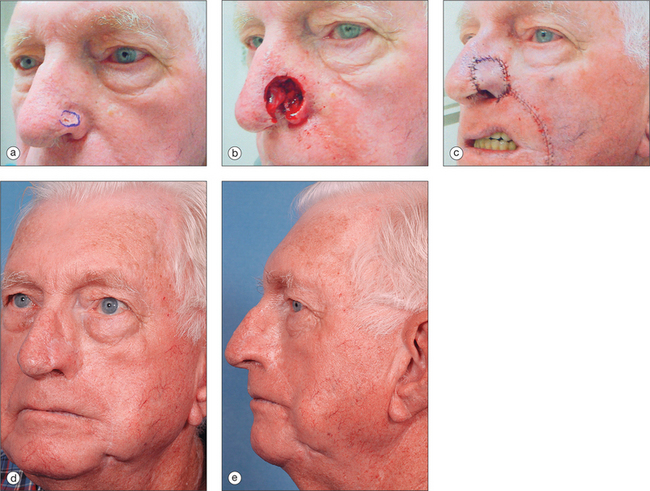

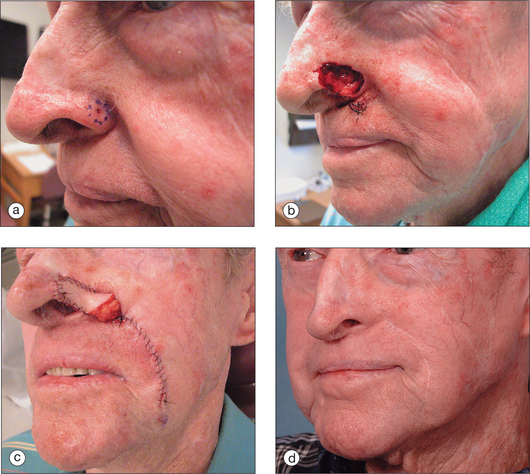

Advancement Flaps

Additionally, such traditional advancement flaps nearly always also depend upon secondary motion around the primary defect’s location in order to close the wound. Such secondary motion typically causes undesirable distal nasal deformation and asymmetry. Advancement flaps can be quite successful, however, in the repair of nasal wounds of medium size (1–2 cm) when the wounds are located on the lateral nasal sidewall and supratip. Such flaps, based on the richly perfused nasalis musculature that covers the entire lateral nose, are viable and uncomplicated repair alternatives (Figures 15.15 and 15.16). The incision lines of this advancement flap are favorably placed along the alar grove and the proximal melolabial crease. As the flap is advanced medially, care must be taken to accurately excise the superior dog-ear redundancy that results from flap motion, to excise a crescent of tissue along the alar groove to prevent ipsilateral alar depression, and to place tacking sutures in the area of the nasofacial groove in order to prevent an unaesthetic “bridging” of this normally shadowed concavity. Like all tacking sutures placed in facial flaps, the deep bite of the suture should attempt to capture the underlying tissue in the area of the piriform aperture, and the superficial bite of the tacking suture should be placed longitudinally along the axis of the flap in order to prevent the introduction of unnecessary ischemia. Additionally, tacking sutures should be placed deep enough within the leading edge of the flap so that an unaesthetic “dimple” in the skin’s surface is not created.

Figure 15.16 This schematic drawing illustrates the type of advancement flap depicted in Figure 15.14. Although the inferior incision line of the flap is logically placed within the alar groove, as the flap is advanced, simple suturing of the flap to the existing secondary defect would result in predictable depression of the lateral aspect of the ipsilateral ala. Instead, a curved redundancy is removed along the flap’s edge, and the location of the entire alar groove remains protected. Because the flap is richly perfused, this excision along the flap’s margin does not compromise the flap’s viability.

The island pedicle flap can be conceptualized as a simple V–Y advancement flap. The island pedicle flap is an attractive repair option for deeper wounds of the face because the flap’s centrally located thick, muscular pedicle produces a flap nearly impervious to ischemia. For this reason, the island pedicle flap is useful for critically located facial wounds, particularly when factors such as exposed cartilage/bone or a history of previous radiation therapy would predict potential ischemia with other reconstructive alternatives. For nasal reconstruction, the island pedicle flap has potential utility for deeper wounds located along the lateral nasal sidewalls and for select wounds along the lateral nasal tip. The flap is particularly useful when the inferior limb of the flap can be placed along the alar groove14 (Figure 15.17). Although the island pedicle flap has been touted as a reconstructive option for a far greater range of nasal wounds,15 the secondary motion inherently associated with the island pedicle flap’s creation often leads to unacceptable distortion of the nasal tip or ala.16 Regardless of the undermining strategy used to provide flap motion, care must be taken with the island pedicle flap to anticipate secondary motion at the flap’s recipient site (the primary defect) and to also account for the secondary motion required to close the flap’s donor site as the flap advances. Along the nose, motion at the primary defect can produce distracting asymmetry, and the motion at the flap’s donor site can often create additional deformity. The utility of the island pedicle flap is also occasionally limited by the fact that distal nasal skin is thick and sebaceous, and this skin, especially when used to create the inherently bulky island pedicle flap, can depress the alar tip or ala as the flap advances into place.

In addition to the traditional island pedicle flap, in which a central, muscle-containing pedicle nourishes the flap, there are also many previously described variants of the island pedicle flap (including bipedicle flaps with central undermining17 and flaps that move along a single lateral muscular “hinge”18). A particularly valuable variant of the island pedicle is the buried or tunneled flap useful in reconstructing deeper wounds near the nasal vestibule. The flap originates in the sebaceous skin along the melolabial fold, and the flap, once adequately mobilized, is tunneled under the cutaneous portion of the upper lip, where it is brought into the surgical defect under minimal tension (Figure 15.18).

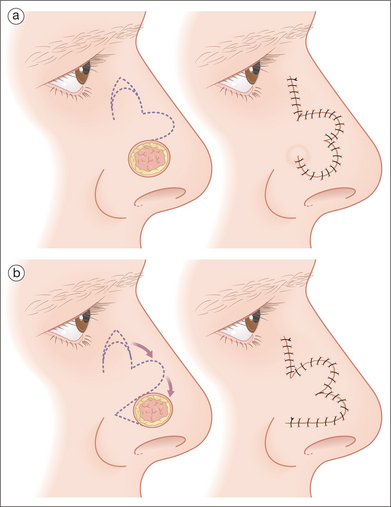

Rotation Flaps

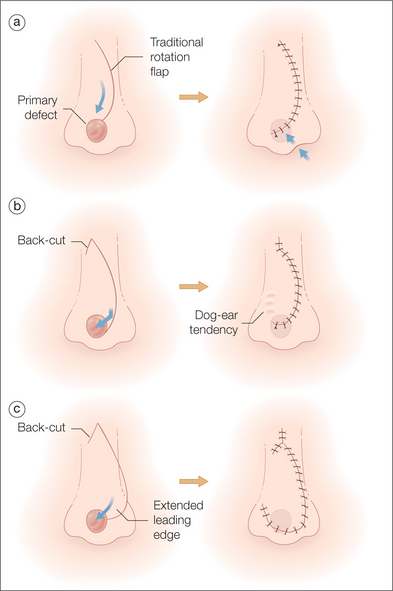

Rotation flaps are conceptually simplistic flaps that utilize a curved incision to liberate a flap of skin that rotates to cover a primary defect. As the rotation flap moves into the surgical defect, a small dog-ear redundancy may develop near the flap’s pivot point. Additionally, the typically circular primary defect also develops a redundancy upon flap motion that must be properly addressed and triangulated if appropriate flap contour is to be achieved. In order to minimize the tension on the rotation flap and to reduce the secondary motion inevitably associated with the flap’s creation, rotation flaps typically require incisions much longer than would usually be required with the creation of many other types of cutaneous flaps. Because long incision lines on the nose are often undesirable and because the secondary motion required to close rotation flaps’ donor sites can be associated with the production of significant nasal distortion, traditional rotation flaps are useful for only a small percentage of nasal defects. Wounds located distally near the alar groove can be occasionally repaired with a hemi-nasal rotation flap, where the dog-ear redundancy near the primary defect can be excised along the alar groove (Figure 15.19).

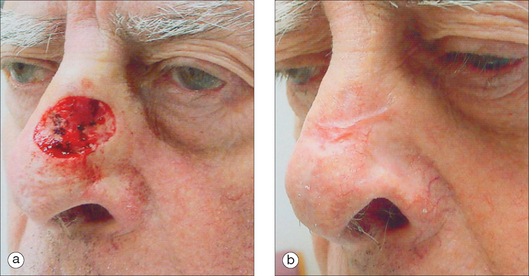

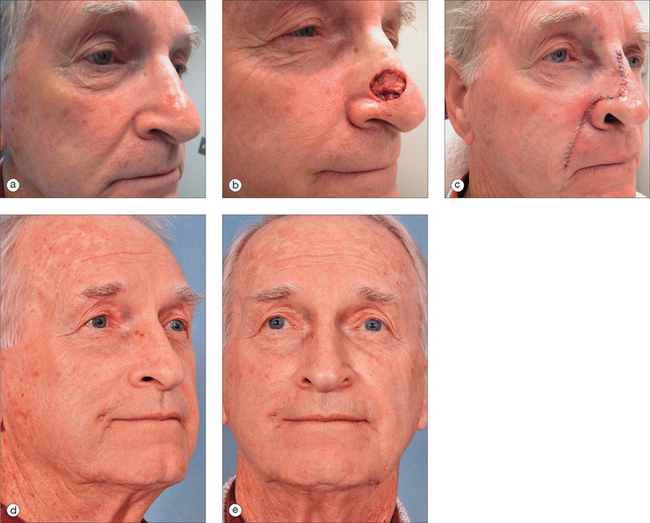

The rotation flap that has the greatest utility in nasal reconstruction is the dorsal nasal rotation flap, a flap originally described by Rieger in 1967.19 The proper use of the flap depends entirely upon the mastering of rotation flap concepts, and the utility of the flap has been traditionally underestimated because of a failure to appropriately modify the flap’s design to reflect the nuances of proper rotation flap creation. The dorsal nasal flap is typically used for deeper distal nasal defects greater than 1.5 cm in diameter (Figure 15.20). For smaller nasal wounds, there are typically other flap reconstructive options that have shorter incision lines, less complicated designs, and fewer undermining requirements. The wound ideally suited for the dorsal nasal flap is a moderately sized wound located on the central nasal tip or supratip. Distally located wounds (along the alar rim, for example) are more difficult to repair with the flap without introducing alar asymmetry. To minimize the tension on the flap and to reduce the likelihood that the secondary motion around the flap’s donor site along the nasal sidewall will be associated with significant distortion, the length of the arc of the flap must be generous. As such, the flap is nearly always required to extend into the area of the glabella. Of course, longer incision lines create the possibility of dramatic flap visibility if improper surgical technique is utilized.

In addition to a lengthy arc, the dorsal nasal flap should have an extended leading edge in order to reduce the possibility of nasal distortion produced when the flap undergoes some degree of relative “shortening” as the flap rotates distally20 (Figure 15.21). If unaccounted for, this shortening (associated with the flap’s pivotal restraint21) will produce elevation of the ipsilateral alar margin, and this design problem, frequently visible in examples in reconstructive texts, accounts for the traditional admonitions that the flap produces less than aesthetically ideal results. If the dorsal nasal flap has sufficient length and an extended leading edge to compensate for the inevitable flap tethering that occurs around the pivot point, the flap can extend to even very distal nasal defects without producing significant tip asymmetry. In addition to proper design, the dorsal nasal flap must also be skillfully executed in order to achieve acceptable results. Like with all nasal flaps, the dorsal nasal flap should be carefully incised, liberally undermined, and closed in a layered manner to ensure success. Because the Rieger flap requires that the entire skin and subcutaneous tissue of the nose rotate under minimal tension to reach distal surgical defects, the proper undermining of the flap is essential. The flap and the surrounding tissue should be generously undermined for the entire distance of the nose. When undermining and thinning the flap, the surgeon should take care to preserve the dorsal nasal flap’s perfusion, which is largely based on the highly anastomotic network of vessels present in the area of the medial canthus. Undermining the dorsal nasal flap, like undermining of all nasal flaps, at the level of the perichondrium increases flap vascularity, minimizes bleeding, liberates the flap by releasing the fascial connections of the subcutaneous tissue to the underlying cartilage, and promotes more aesthetic scars.22 Additionally, because the skin of the glabella is typically thick and relatively sebaceous, this area of the flap must be thinned, as the medial canthal skin that receives this portion of the flap is typically very thin-skinned, and the inherent mismatch in contour is often quite visible and cosmetically unacceptable if not compensated for during the repair.

Transposition Flaps

There are several transposition flaps that serve as reliable alternatives to reconstruct even complicated nasal wounds. The prototypical transposition flap is the rhombic flap, a simple design in which a triangulated flap is used to cover an adjacent wound.23 Although transposition flaps are conceptually more difficult to envision than simpler advancement and rotation flaps, their use on the nose can be very appropriate when proper cases are selected.

The rhombic flap has its greatest utility in the repair of surgical wounds located on the proximal nose and the nasal sidewall. The flap is an ideal choice to harvest the looser skin of the proximal sidewall and dorsum to cover wounds located more distally, where the tissue immediately adjacent to the wound might not be sufficiently mobile (Figure 15.22). Because the incision lines of the single-lobe transposition flap are shorter and less complicated than the incision lines of other transposition flaps such as the bilobed flap, there is a tendency to attempt to use the simple rhombic flap for very distal nasal tip or alar wounds. This is nearly always unsuccessful, as the thick skin of the more proximal nasal tip tends to depress the alar margin as it moves inferiorly. Also, the donor site of these distally located flaps, located within thickly sebaceous nasal skin, cannot be closed without dramatically increasing the likelihood of producing significant deformity. For these reasons, the use of the simple rhombic flap is nearly always limited to the repair of wounds located along the nasal dorsum or nasal sidewalls or in the area of the glabella.24

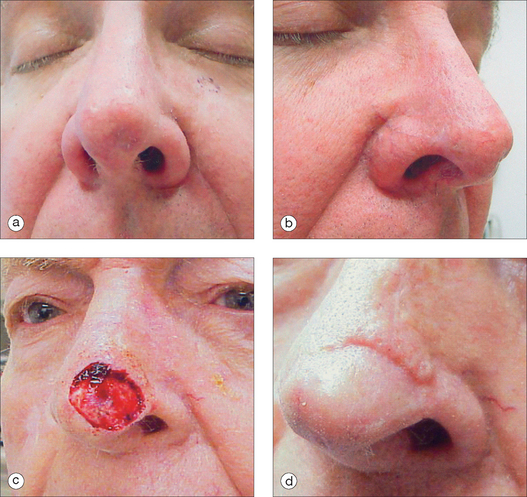

The bilobed flap, initially described by Esser in 1918,25 was of limited use until Zitelli introduced significant improvements in the flap’s design in 198926 (Figure 15.23). Even though the bilobed flap does not follow relaxed skin tension lines and does not repair the nose using the subunit principle, the flap does offer an ability to transpose sebaceous skin onto the nasal tip without producing alar asymmetry (Figure 15.24). The design of the bilobed flap is an intricate arrangement of adjacent rounded flaps that rely upon the availability of tissue along the nasal dorsum. In order to prevent alar distortion, careful attention should be placed on the magnitude and direction of the flap’s Burow’s triangle excision, on the location and sizing of the primary and secondary lobes, and on the utilization of meticulous operative technique.

In order to prevent unwanted secondary motion around the primary defect along the distal nose, the flap’s primary lobe should be roughly equal in size to the primary defect. Similarly, the secondary lobe of the flap should be almost equally sized with the primary lobe in order to reduce the likelihood of unaesthetic alar elevation.27 Attention should also be placed on the exact arrangement of the lobes’ origination points, as small amounts of secondary motion required to close the operative defects can produce significant amounts of nasal distortion. Despite the complexity of the bilobed flap’s design, the flap, once mastered, is an impressively predictable reconstructive choice for nasal tip defects.

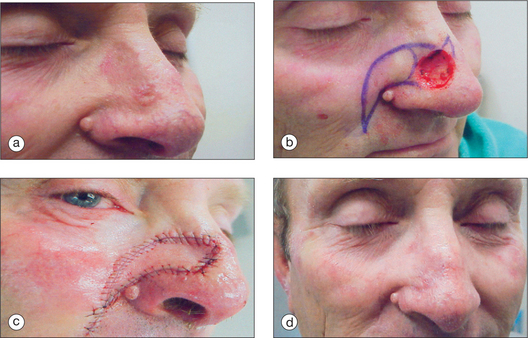

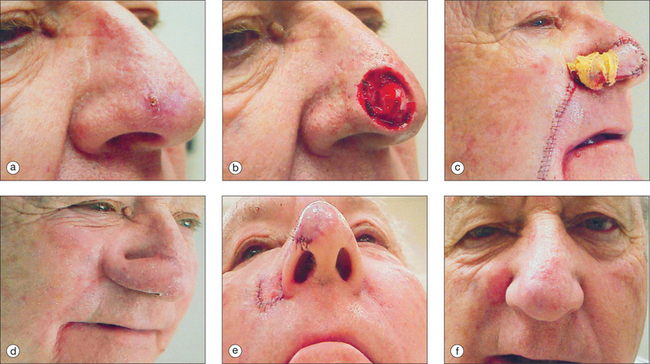

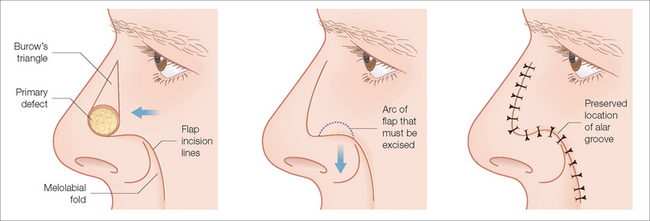

The nasolabial (or, more properly, the melolabial) transposition flap is another traditional flap used to repair nasal defects (Figure 15.25). This flap relies on the color and textural similarities between the sebaceous skin of the lateral nasal ala and the available skin of the melolabial crease. The flap offers a one-step reconstruction of surgical defects in the areas of the nasal ala and the very lateral portions of the nasal tip.28 The donor morbidity of the flap can be minimal given the flap’s origin directly within the melolabial crease. Additionally, the thickness of the flap can be easily manipulated, and the flap can be used to cover even deeper wounds along the distal nose. Because the flap relies upon the redundancy of vasculature in the areas of the medial cheek and medial canthus, the flap is uncommonly subject to ischemia.29

Because the melolabial flap is particularly prone to developing the trapdoor deformity, careful attention should be placed on strategies to prevent this complication, which frequently turns the flap into a finger-like protuberance along the distal nose30 (Figure 15.26). The most important strategy to avoid the production of a flap redundancy is to avoid oversizing the flap—either in width or in thickness.31 Additionally, deep tacking sutures should anchor the flap at the flap’s pivot near the junction of the cheek and nose and along the flap’s undersurface in the area of the former alar groove. Although it may be possible to recreate the medial aspect of the alar groove in some patients, tacking techniques seldom offer appropriate recreation of the lateral aspect of the groove.

In addition to the traditional version of the melolabial flap, the flap can also be modified to reconstruct even full-thickness wounds along the lateral alar margin. One particularly valuable variation of the melolabial fold involves folding the flap onto itself in order to provide both internal lining and external coverage in the repair of challenging full-thickness alar wounds32 (Figure 15.27).

Interpolation Flaps

Interpolation flaps are pedicled flaps that cover nasal wounds by transferring tissue from areas not immediately adjacent to the primary defect across relatively large expanses of intervening normal skin. These flaps offer unparalleled opportunities to repair difficult nasal wounds, but their use is limited by the fact that the flaps require two surgical procedures (flap pedicle creation and flap separation/insertion) that are typically separated by a several-week period of flap attachment, during which the patient must contend with an unsightly flap appearance. Despite this obvious disadvantage, pedicled flaps offer great utility in the repair of larger nasal wounds, especially when local tissue is insufficiently available to create single-staged random pattern cutaneous flaps from the remaining nasal or cheek skin.

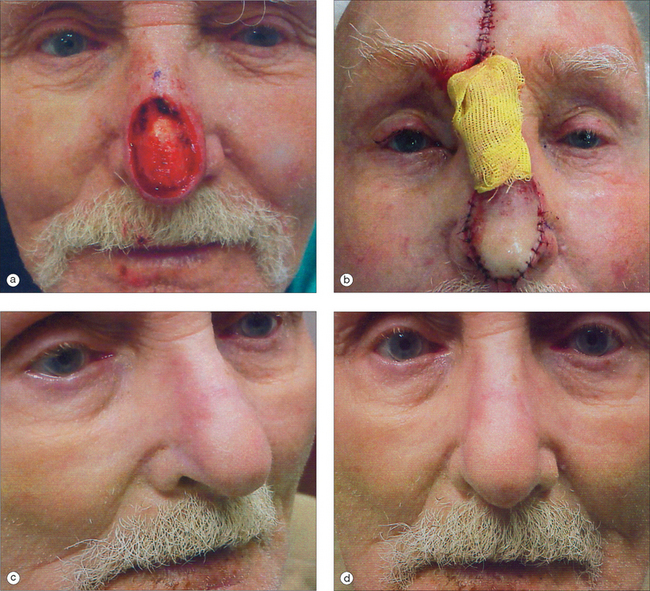

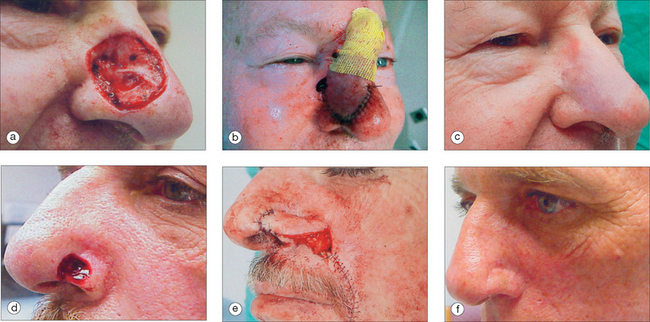

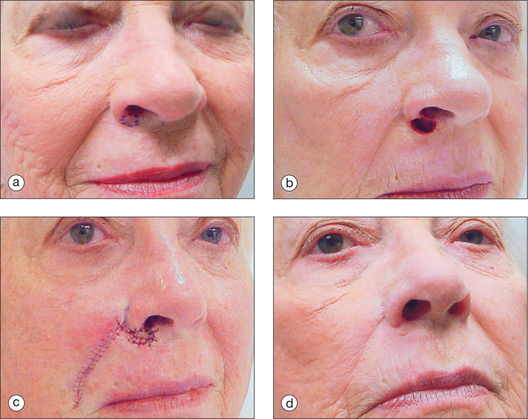

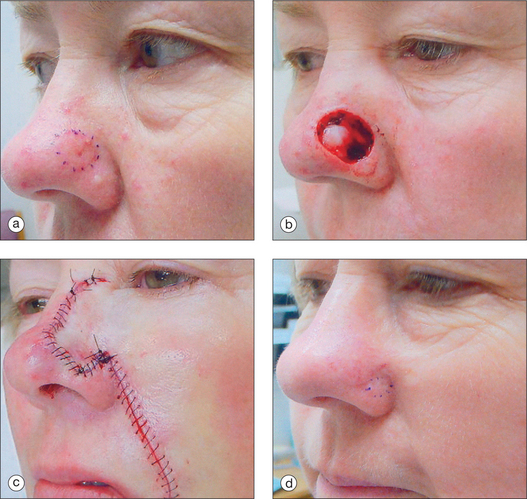

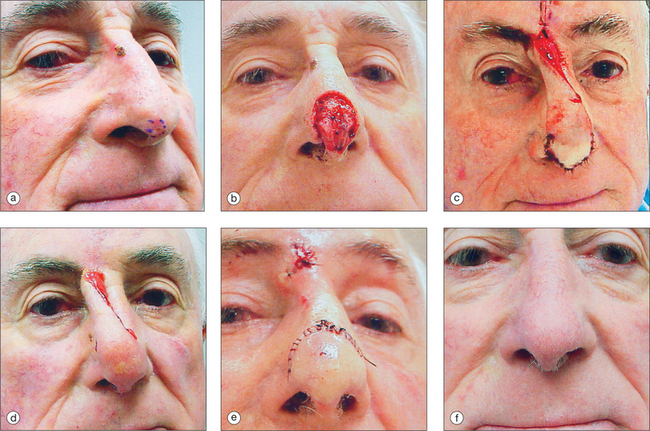

The pedicled melolabial (nasolabial) flap is a particularly valuable flap for reconstructing difficult wounds of the distal nose (Figure 15.28). Similar to the traditional (single-step) melolabial flap, this flap’s donor site is relatively hidden within the melolabial crease on the medial cheek. Wounds particularly well-suited for this interpolated flap repair are deeper wounds of the ala (Figure 15.29). Because the pedicled melolabial flap remains temporarily attached to its donor site on the medial cheek, the flap is not required to transpose over the remaining alar groove in order to cover the wound. Thus, this pedicled melolabial flap is particularly valuable in reconstructing alar wounds in which the alar groove has been largely spared (Figures 15.4d–f). This pedicled flap is also very useful in reconstructing difficult to reach areas of the nose such as the very medial aspect of the alar rim in the columella or the area of the soft triangle.

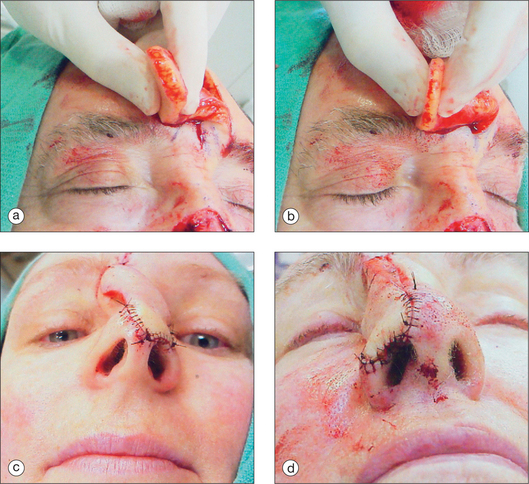

The donor site of the flap is placed within the melolabial fold, and a cotton sponge is used to ensure that the flap will reach the nasal defect because the flap undergoes predictable “shortening” as the flap rotates into the surgical defect. Although the flap is distally thinned to nearly dermis in order to prevent a globular appearance to the flap, the proximal portion of the pedicled flap is deeply undermined so that the highly perfused medial cheek musculature supports the vascular demands of the flap.33 The flap is sutured under minimal tension. If minor degrees of alar or columella distortion are apparent, they typically resolve when the flap is separated (Figure 15.30). At the time of flap separation, traditionally performed at three weeks after the flap’s creation, the flap is severed and thinned to match to the contour of the nose. The donor site in the medial cheek can be linearly inserted as a continuation of the newly created melolabial fold or inserted as a small U-shaped closure at the proximal end of the fold. The latter approach may be preferable in patients with deeper melolabial folds, as the shadowing of the fold will likely be preserved at least in this proximal portion of the donor site.

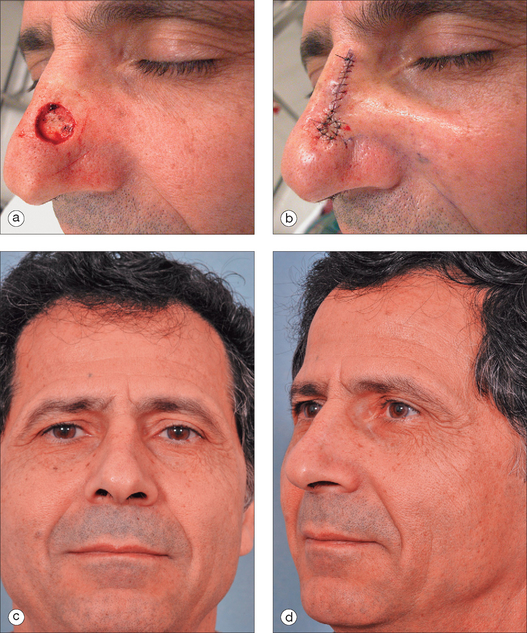

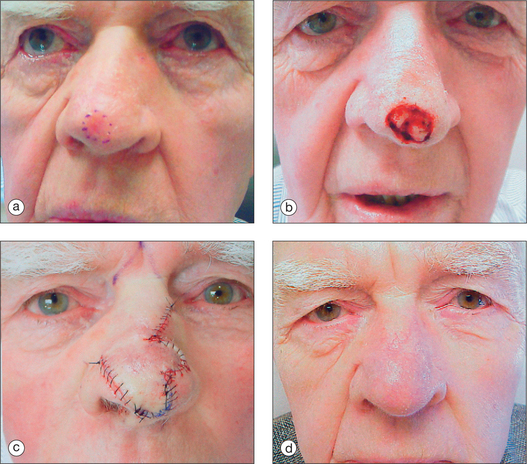

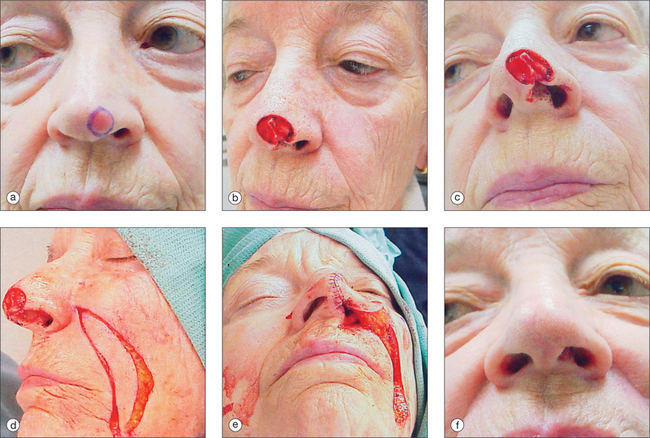

Perhaps the most versatile of the pedicled flaps used to reconstruct more challenging wounds of the nose is the paramedian forehead flap, an axial patterned flap designed around the predictable location of the supratrochlear artery. Because the visual significance of the forehead is minuscule when compared to the aesthetic prominence of the nose, even large areas of the forehead can be sacrificed to cover complicated nasal wounds (Figure 15.31). The forehead flap’s advantages include its ability to reach nearly any area of the nose (regardless of the size of the wound), its luxurious vascular supply and relative immunity to ischemia, and the similarity in color and texture between forehead and nasal skin. The forehead flap, a viable reconstructive option for most larger nasal wounds, has several potential disadvantages. Besides the obvious need to place a relatively large donor wound on the forehead and the need to perform a second surgical procedure to separate and insert the flap, the forehead flap is also limited by the tendency for the flap to undergo a trapdoor deformation as the flap matures. For that reason, the design and execution of the forehead flap are particularly important. If proper design and technique are not used, it is quite possible for the forehead flap to appear as an undefined spherical “blob” rather than as a normal nasal tip.

The forehead flap is ideal for nasal wounds that lack suitable random pattern nasal flap solutions. Because the forehead flap’s perfusion is so predictably protected, the flap is particularly appropriate for deeper wounds that also require the introduction of relatively avascular structural elements such as cartilage. If alar flaccidity has introduced functional concerns, plans should obviously be made to reconstruct the rigidity and flexibility of the distal nose in addition to designing skin coverage. If the wound involves a majority of any aesthetic subunit of the nose, consideration should be given toward enlarging the size of the primary defect until the borders of the adjacent aesthetic subunits have been reached2 (Figure 15.32). Placing the incision lines of the flap along theses boundaries will often improve the aesthetic subtlety of the flap’s final appearance. Even if the flap does not replace the entire aesthetic subunit, aesthetically appropriate results can be achieved if the color and texture of the flap offer a suitable match to the adjacent skin.34 After the defect has been evaluated, a three-dimensional model of the missing nasal tissue is constructed from the foil of a suture package, using the contralateral nose as a model in the case of unilateral nasal wounds. The approximate location of the supratrochlear artery is located using the corrugator fold near the medial brow. Although a Doppler device can confirm the location of the artery, the artery’s location is so predictable that an exact confirmation of the artery’s location is typically unnecessary. The flap should be constructed with a pedicle width of no greater than 1.5 cm. Larger widths would seemingly offer greater assurance that the surgeon has appropriately included the nourishing artery within the flap’s base, but this greater pedicle width actually causes difficulty in rotating the flap under minimal tension. The flap should extend far enough superiorly on the forehead so that the flap can reach the nasal defect under essentially no tension. Rather than extend the flap into the hair-bearing scalp, the surgeon can gain additional flap length by safely extending the flap’s origin below the bony orbital margin. At the origin of the flap, the supratrochlear artery is located between the frontalis and the corrugator musculature, and care should be taken with flap undermining to preserve the narrow artery’s integrity. As the supratrochlear artery courses up the forehead, the artery becomes nearly subdermal in location.35

If the forehead flap is not thinned at its distal margin, the skin of the forehead will nearly always be thicker than the missing skin and soft tissue of the distal nose. Placing this untrimmed flap onto the nose will therefore result in a globular, amorphous mass rather than the delicate arrangement of convexities and concavities that defines the appearance of the normal nose (Figure 15.33). Thinning the flap, however, comes at a price; such thinning inevitably threatens the flap’s perfusion to some degree. Flap thinning should there-fore be undertaken with great care, particularly in smokers, for whom the risks of flap necrosis are higher. During the initial flap transfer, the distal 1.5–2 cm of the forehead flap can typically be thinned to nearly the underlying dermis, leaving only a thin layer of residual subcutaneous fat. This produces a flap whose thickness is very close to the thickness of distal nasal skin, and the thinning produces a flap that is essentially random patterned at its insertion point. After a period of delay (traditionally three weeks), the flap is separated from its glabellar attachment and inserted onto the nose. At this time the more superior aspects of the flap that were not aggressively thinned during the original flap creation can be now appropriately sculpted. Because the skin of the proximal nose is thinner than the sebaceous skin of the nasal tip, thinning of the flap along the nasal dorsum and sidewalls is especially important (Figure 15.32). On occasion, the pedicle of the forehead flap is allowed to remain attached, and the flap is lifted off of the wound bed while keeping both the proximal pedicle and the distal insertion intact. The flap can be very aggressively thinned at this point since the perfusion is quite redundant, and the flap is subsequently separated at three weeks after this interim revision procedure.36 This interim thinning procedure can eliminate the occasional need to perform a sculpting procedure 6–12 months after the original reconstructive procedure in order to restore proper contour to the nose.

COMPLICATIONS

All surgical procedures have risk, and nasal reconstructive procedures are certainly fraught with potential complications if appropriate reconstructive alternatives are not carefully selected, designed, and executed. Like with any cutaneous surgical procedure, complications such as bleeding and wound infection occasionally accompany nasal repairs. These complications can usually be minimized or avoided if proper operative care is utilized. Functional complications such as alar collapse can occur if the reconstructive procedure addresses only the nose’s skin coverage and not its underlying structural support. For this reason, it is imperative to properly assess the need to reintroduce structural rigidity (with the use of cartilage grafts)37 prior to repairing deeper nasal wounds with weighty flaps. In addition to functional difficulties, many nasal repairs, particularly flap procedures, can introduce significant alar asymmetry if the nuances of flap motion are not fully understood. Flap and skin graft necrosis can also occur with many nasal repair options, but tissue necrosis does not seem to be apparent with greater frequency on the nose than at any other facial location. Indeed, the liberally perfused underlying musculature of the nose nourishes both skin grafts and flaps quite readily, and ischemic complications in nasal reconstructive surgery are quite uncommon if expert technique is utilized. Two complications seen in nasal reconstructive surgery with a greater frequency than at other facial sites include the presence of very visible incision lines and the development of the trapdoor (or pin-cushioned) deformity.

The presence of visible incision lines with nasal repairs is simply a reflection of the nose’s aesthetic prominence in the central face and the fact that sebaceous, thick skin, regardless of site, tends to heal with more inverted, visible incision lines. For this reason, particular attention should be placed upon placing nasal incision lines along aesthetic boundaries, using layered closures to minimize the tension on the overlying epidermis, and promoting appropriate wound edge eversion with proper suture technique.38 Elective laser resurfacing or dermabrasion of nasal repairs can often minimize the appearance of prominent incision lines,35 but even gently performed resurfacing procedures can introduce undesirable pigmentary and textural changes to the skin.

The trapdoor deformation of nasal flaps typically begins at three to six weeks after a reconstructive procedure. The deformity is characterized by the development of a protuberant, globular-appearing flap, and the deformity is likely due to the centrifugal contraction of plate-like scar tissue under the nascent repair.39 To prevent the trapdoor deformation of nasal flaps, the cutaneous surgeon should undermine the nasal recipient site liberally,30 thin flaps generously, and, perhaps most importantly, avoid oversizing flaps.31 If the trapdoor deformity develops, intralesional injections of corticosteroids can usually be quite effective.

If nasal reconstructive procedures are aesthetically or functionally unsuccessful, surgical revision procedures can certainly be offered. The most expertly performed revision procedure, however, cannot compare with the proper initial performance of the reconstructive procedure, and the surgeon should therefore be advised to design and perform nasal reconstructive procedures that leave little need for later revision. If the most well-intentioned repair nonetheless fails, revision techniques (dermabrasion, flap “sculpting,” z-plasty reorientations of scars, introduction of structural elements such as cartilage, flaps, and grafts to correct alar notching, etc.) can certainly be contemplated. The surgeon is cautioned, however, that such repair options can be much more difficult to perform than the original reconstructive procedure and that the results from such repairs are often less than ideal.

1 Burget GC, Menick FJ. Aesthetics, visual perception, and surgical judgment. In: Burget GC, Menick FJ, editors. Aesthetic reconstruction of the nose. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1994:1-55.

2 Burget GC, Menick FJ. Sub-unit principle in nasal reconstruction. Plas Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:239-247.

3 Burget GC, Menick FJ. Repair of small surface defects. In: Burget GC, Menick FJ, editors. Aesthetic reconstruction of the nose. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1994:117-156.

4 Zitelli JA. Wound healing by first and second intention. In: Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH, editors. Dermatologic surgery. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1996:101-130.

5 Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL. Long term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: Implications for patient follow-up care. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:315-328.

6 Bumstead RM, Ceilly RI. Auricular malignant neoplasms. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108:225-231.

7 Cook J, Zitelli JA. Primary closure for midline defects of the nose: A simple approach to reconstruction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:508-510.

8 Zitelli JA. Burow’s grafts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:271-279.

9 Rohrer TE, Dzubow LM. Conchal bowl skin grafting in nasal tip reconstruction: clinical and histologic evaluation. J Amer Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:476-481.

10 Kaplan A, Cook JL. The incidences of chondritis and perichondritis associated with the surgical manipulation of auricular cartilage. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:58-62.

11 Goldminz G, Bennett RG. Cigarette smoking and flap and full-thickness graft necrosis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1012-1015.

12 Davenport M, Daly J, Harvey I, Griffiths RW. The bolus tie-over “pressure” dressing in the management of full-thickness skin grafts: Is it necessary? Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:28-32.

13 Cook JL, Perone J. A prospective analysis of complications associated with Mohs’ micrographic surgery. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:143-152.

14 Rybka FJ. Reconstruction of the nasal tip using nasalis myocutaneous sliding flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71:40-48.

15 Papadopoulos DJ, Trinei FA. Superiorly based island pedicle flap with bilevel undermining for nasal tip and supratip reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:530-536.

16 Burget GC. Commentary on the bipedicle nasalis musculocutaneous flap. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:916-917.

17 Millman B, Klingensmith M. The island rotation flap: a better alternative for nasal tip repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1293-1297.

18 Hairston BR, Nguyen TH. Innovations in the island pedicle flap for facial reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:378-385.

19 Rieger RA. A local flap for repair of the nasal tip. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 1967;40:147-149.

20 Dzubow LM. Dorsal nasal flaps. In: Baker SR, Swanson NA, editors. Local flaps in facial reconstruction. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1995:225-246.

21 Dzubow LM. The dynamics of flap movement: Effect of pivotal restraint on flap rotation and transposition. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:1348-1353.

22 Tardy ME. Topographic anatomy and landmarks. In: Tardy ME, editor. Surgical anatomy of the nose. New York: Raven Press; 1990:1-23.

23 Limberg AA. Design of local flaps. In: Gibson T, editor. Modern trends in plastic surgery. London: Butterworth; 1966:38-61.

24 Field LM. The glabellar transposition “banner” flap. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:376-379.

25 Esser JSF. Gestielte locale Nasenplastik mit zweiplifgem Lappen, Deckung des sekundaren Defektes vom ersten Zipfel durch den zweiten. Dtsch Z Chir. 1918;143:385-390.

26 Zitelli JA. The bilobed flap for nasal reconstruction. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:957-959.

27 Cook JL. A review of the bilobed flap’s design with particular emphasis on the minimization of alar displacement. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:354-362.

28 Zitelli JA. The nasolabial flap as a single-stage procedure. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1445-1448.

29 Lindsey WH. The reliability of the melolabial flap for alar reconstruction. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:33-37.

30 Koranda FC, Webster RC. Trapdoor effect in nasolabial flaps. Causes and corrections. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111:421-424.

31 Field LM. The nasolabial flap—a definitive reappraisal. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:429-436.

32 Spear SL, Kroll SS, Romm S. A new twist to the nasolabial flap for reconstruction of lateral alar defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:915-920.

33 Fosko SW, Dzubow LM. Nasal reconstruction with the cheek island pedicle flap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:580-587.

34 Singh DJ, Bartlett SP. Aesthetic considerations in nasal reconstruction and the role of modified nasal subunits. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:639-648.

35 Yarborough JMJr. Ablation of facial scars by programmed dermabrasion. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:292-294.

36 Menick FJ. A 10-year experience in nasal reconstruction with the three-staged forehead flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1839-1855.

37 Byrd DR, Otley CC, Nguyen TH. Alar batten cartilage grafting in nasal reconstruction: functional and cosmetic results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:833-836.

38 Zitelli JA, Moy RL. Buried vertical mattress suture. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:17-19.

39 Hosokawa K, Susuki T, Kikui T, et al. Sheet of scar causes trapdoor deformity: a hypothesis. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;25:134-135.