CHAPTER 34 MYOCLONUS

The term myoclonus originates from report of a case by Friedreich in 1881 with the title of “paramyoclonus multiplex.” The patient was a 50-year-old man manifesting involuntary small muscle jerks mostly in the resting state. Myoclonus is defined as involuntary shocklike movements associated with sudden contraction of skeletal muscles (positive myoclonus), sudden interruption of the ongoing muscle contraction (negative myoclonus), or a combination of the two.

CLASSIFICATION

Myoclonus can originate from either the central nervous system or the peripheral nervous system, but most of myoclonic jerks occur in association with disorders of the central nervous system.1 It can originate from the motor cortex, brainstem, and spinal cord, and there are some other forms of myoclonus whose source has not been clarified completely (Table 34-1). Cortical myoclonus occurs either spontaneously or through a reflex mechanism in response to external stimulus (cortical reflex myoclonus). Epilepsia partialis continua is a focal, continuous form of cortical myoclonus, usually involving the distal part of the upper or lower limb. Cortical myoclonus is often epileptic in nature and thus is also called epileptic myoclonus. Palatal tremor, reticular reflex myoclonus, and startle syndrome are known to originate from brainstem structures. There are two forms in spinal myoclonus: segmental and propriospinal. Periodic myoclonus and dystonic myoclonus are easily recognized from their unique clinical features, but their underlying mechanisms have not been elucidated precisely.

CLINICAL FEATURES

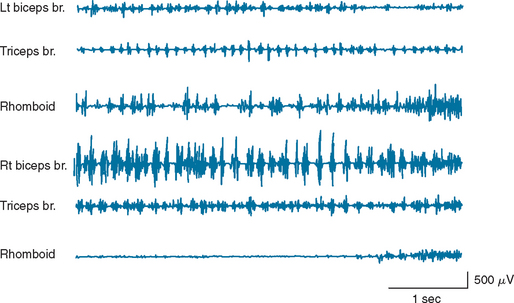

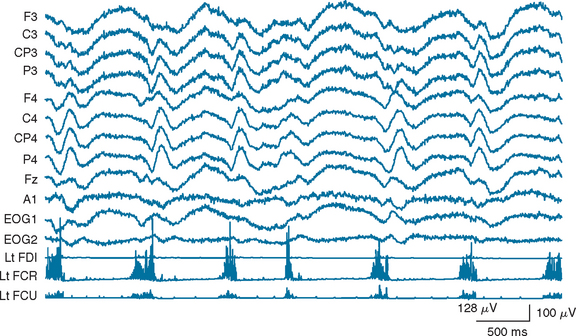

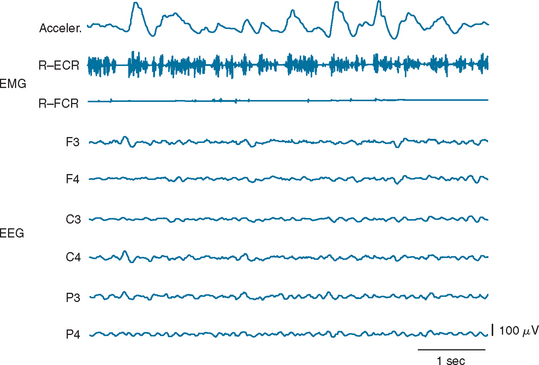

Cortical myoclonus appears as brisk, shocklike movements involving fingers, hands, arms, facial muscles, and/or legs, and sometimes trunk muscles, independently (Fig. 34-1). When hand intrinsic muscles are involved, it appears as small twitches of each individual finger or a group of fingers. When, in contrast, proximal muscles of an extremity are involved, it appears as big jerks. When the jerks rapidly spread from proximal to distal muscles of an extremity, it appears as if the whole extremity is involved almost simultaneously. Moreover, a jerk of one hand can be followed by another jerk in the other hand by a very short time interval: in fact, as short as 10 milliseconds, corresponding to the transcallosal conduction time. In this case, it appears as if both upper extremities are almost simultaneously involved. Cortical myoclonus appears rhythmic when it repeats in the same muscle groups at a fast rate (7 to 8 Hz), and thus it often resembles tremor (cortical tremor) (Fig. 34-2). Rhythmic cortical myoclonus is commonly seen in corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, familial adult myoclonic epilepsy, postanoxic myoclonus, and Angelman’s syndrome.

Cortical myoclonus sometimes manifests as negative myoclonus, which is caused by sudden interruption of the ongoing muscle contraction (silent period of the electromyogram [EMG]). Most of the negative myoclonus are either immediately preceded or immediately followed by abrupt muscle contraction (positive myoclonus), but on occasion, the isolated form of negative myoclonus is seen. Thus, the pure negative myoclonus can be easily overlooked unless the extremity is examined during sustained muscle contraction: for example, while the wrists are kept in an extended posture. When the trunk muscles are suddenly involved by negative myoclonus, the patient may fall down abruptly (drop attack). On occasion, negative myoclonus is induced by somatosensory or photic stimulus through a transcortical reflex mechanism (cortical reflex negative myoclonus).

Palatal tremor used to be called palatal myoclonus, but the name was changed after the first International Congress of Movement Disorders, held in Washington, D.C., in 1990, because of the lack of shocklike features and its resemblance to tremor, especially when other skeletal muscles are also involved. Essential palatal tremor is characterized by repetitive elevation of the soft palate at a rate of 2 to 3 Hz, often associated with ear click. Familial cases of essential palatal tremor have been reported. The movement may be associated with repetitive, brisk muscle contractions of other cranial muscles, which are approximately synchronous with the palatal movement. Symptomatic palatal tremor consists of rhythmic vertical oscillation of the soft palate and is frequently associated with rhythmic vertical oscillation of eyes (ocular myoclonus). This condition is commonly associated with organic lesions of brainstem or cerebellum and often involves other cranial and extremity muscles. In this condition, the movement of extremities is not very shocklike and may resemble real tremor. This form of palatal tremor may be persistent even during sleep.

Underlying mechanisms have not been disclosed for other kinds of myoclonus, including periodic myoclonus and dystonic myoclonus. There are two representative forms of periodic myoclonus; one seen in CJD and the other seen in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Periodic myoclonus seen in CJD is quasi-periodic repetition of shocklike, quasi-synchronous jerks involving extremities and facial muscles at a rate of about 1 Hz. It might shift from one extremity to others and continue during sleep, although the rate and the periodicity might change from time to time. It is often associated with periodic synchronous discharge (PSD) on electroencephalographic (EEG) recording, but there is no fixed time relationship between PSD and periodic myoclonus in this condition (Fig. 34-3).

UNDERLYING DISEASES

Myoclonus can be caused by a number of different diseases. Representative diseases causing cortical myoclonus are listed in Table 34-2. Progressive myoclonus epilepsy is a group of diseases manifesting postural/action myoclonus and generalized convulsive seizures. Most of them are hereditary, and gene abnormalities have been identified for many of these diseases (Table 34-3).2 Among other diseases, postanoxic myoclonus (Lance-Adams syndrome) is most commonly encountered. In this condition, myoclonus develops in patients who survived the acute phase of anoxic encephalopathy, and it is often refractory to various drug treatments. Most jerks are of cortical origin, although reticular reflex myoclonus has been described in this condition. In contrast with progressive myoclonus epilepsy, generalized convulsive seizures are rather rare in this condition.

TABLE 34-3 Major Forms of Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy and Their Gene Abnormality

| Disorder | Locus/Chromosome | Gene Product |

|---|---|---|

| Unverricht-Lundborg disease | EPM1/21q22.3 | Cystatin B |

| Lafora’s disease | EPM2A/6q24 | Laforin (dual-specificity phosphatase) |

| EPM2B/6p22.3 | Malin | |

| MERRF | MTTK/mtDNA | tRNALys |

| Sialidosis | NEU1/6p21 | Neuraminidase 1 |

| DRPLA | DRPLA/12p13 | Atrophin 1 |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis | ||

| Infantile | CLN1/1p32 | Palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 |

| Late infantile | CLN2/11p15 | Tripeptidyl peptidase 1 |

| Juvenile | CLN3/16p12 | CLN3 (membrane protein of unknown function) |

DRPLA, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy; MERFF, myoclonic epilepsy associated with ragged-red fibers.

Modified from Lehesjoki A-E: Molecular background of progressive myoclonus epilepsy. EMBO J 2003; 22:3473-3478, with help from Dr. Lehesjoki.

It is noteworthy that cortical myoclonus can be present in metabolic encephalopathy, such as the disease caused by uremia. Thus, this condition is not necessarily associated with organic brain lesions and is reversible when the underlying cause is successfully treated. In relation to this, hepatic encephalopathy characteristically shows rhythmic negative myoclonus (asterixis), although the mechanism of this condition is not known.

Many drugs can cause myoclonus as a side effect (drug-induced myoclonus). Myoclonus of this category is often of negative form, associated with the EMG silent period (Fig. 34-4). Thus, whenever negative myoclonus develops in a patient who takes anticonvulsants, this possibility has to be considered. In other words, some cases of negative myoclonus in patients with cortical myoclonus may be, in fact, a side effect of anticonvulsants that they are taking. The physiological mechanisms underlying drug-induced myoclonus may not be homogeneous. It is most likely that some of them may be of cortical origin and the others subcortical.

PHYSIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS

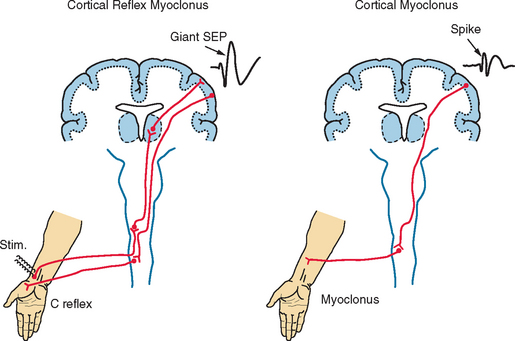

As far as cortical myoclonus is concerned, its physiological mechanisms have been elucidated to some extent. This is because most activities of the sensorimotor cortex are remarkably exaggerated in this condition, which makes it easier to assess those activities physiologically by EEG or magnetoencephalographic recording from the head surface. Cortical myoclonus is characterized by increased excitability of the primary motor cortex, extreme enhancement of cortical response to somatosensory stimulus, and enhanced long-loop, transcortical reflex (Fig. 34-5). When a part of the primary motor cortex is suddenly involved by epileptic activity, the muscles innervated by that particular cortical area show sudden contraction at a latency of about 20 milliseconds for a hand and 40 milliseconds for a foot. The cortical activity related to myoclonus may be actually recognized as a spike on EEG recording. In this condition, the somatosensory cortex reacts to tactile or proprioceptive input with magnitude of 10 times or more in comparison with the physiological reaction. This activity can be recorded as an enormously enhanced (giant) somatosensory evoked potential (SEP). Furthermore, tapping of a hand, for example, elicits reflex muscle contraction in that hand at a latency of about 45 milliseconds. This response can be recorded as an EMG response (long-loop reflex or C reflex) through the use of the surface electrodes.

LABORATORY TESTS

The main laboratory test is aimed at confirming and classifying the myoclonus and understanding its pathophysiology, by using a battery of electrophysiological tests (Table 34-4).3,4 The most essential test for any kind of myoclonus is the EMG recording of myoclonic jerks with the surface electrodes. In order to find the distribution and spread of myoclonus, it is more effective to record simultaneously from as many muscles as possible. This is also useful for finding the most appropriate muscle for carrying out other physiological studies as described later. For recording EMG from a large muscle, a pair of disk electrodes are placed on the skin overlying the muscle belly about 3 cm apart from each other; for recording from a small muscle such as hand intrinsic muscles, one electrode is placed over the muscle, and the other electrode on the skin covering the adjacent bone. A band-pass filter of 30 to 1000 Hz is adequate. Application of low-frequency filter (high-pass filter) is mainly for eliminating movement artifacts.

| Technique | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Surface electromyography | Confirmation of myoclonus and its classification |

| EEG-EMG polygraphy | To know the relationship with cortical activity |

| Jerk-locked back averaging of electroencephalogram | Detection of myoclonus-related cortical activity, and to know its temporal and spatial relationship to myoclonus |

| Somatosensory evoked potential (SEP) | To confirm giant SEPs |

| Long-loop reflex | To confirm the reflex nature of myoclonus |

EEG, electroencephalogram; EMG, electromyogram.

Cortical myoclonus is associated with an EMG discharge of abrupt onset and of short duration, lasting less than 50 milliseconds (see Fig. 34-1). Usually, agonist and antagonist muscles contract simultaneously. The contraction may spread from proximal to distal muscles at the speed of about 50 m/second, which corresponds approximately to the conduction velocity of α motor fibers. In case of hand myoclonus, it may be seen in the homologous muscles of the contralateral upper extremity 10 to 15 milliseconds later.

Simultaneous EEG recording with the surface EMG is especially useful for the confirmation of cortical myoclonus. EEG recording is accomplished by placing electrodes in accordance with the International 10-20 System recommendations. Referential derivation with ipsilateral earlobe reference or bipolar derivation is used. Usually a band-pass filter of 1 to 500 Hz is used. When the number of EEG channels, the recording time, or both are limited, EEG may be recorded from a limited number of electrodes: for example, from C3, Cz, and C4 of the International 10-20 System in reference to the ipsilateral earlobe. Demonstration of spikes or multiple spikes on EEG is highly suggestive of the cortical origin of myoclonus. The spikes may or may not be associated with myoclonic jerks (see Fig. 34-1). Absence of EEG spikes, however, does not rule out the cortical myoclonus, because small spikes may not be detected by the scalp recording as a result of attenuation of the electric potential by the skull. Demonstration of PSD is almost pathognomonic of either CJD or subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, depending on the waveform. EEG findings similar to the CJD type of PSD are sometimes encountered in anoxic encephalopathy, but PSD in this condition is not persistent.

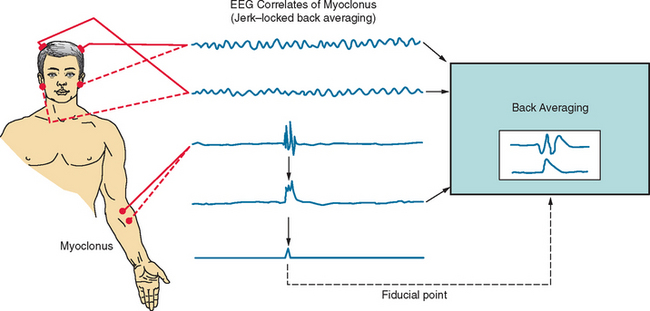

The technique of jerk-locked back averaging can be used for detecting spikes associated with myoclonus that are not detectable on the conventional EEG-EMG polygraph and for investigating the time and spatial relationship between the EEG spikes and myoclonus. EEG and EMG are recorded simultaneously, just as for the conventional polygraph, and the onset of EMG discharges associated with myoclonus is used as a fiducial point for back averaging the EEG (Fig. 34-6). The EMG may be rectified to avoid the canceling effect of averaging, and integrated. The onset of the rectified, integrated EMG waveform is used as a fiducial point for back averaging, as well as for obtaining the averaged EMG waveforms. Averaging of 100 sweeps is usually sufficient, but it is important to confirm the reproducibility of the results. In order to obtain a record of high quality, it is important to choose the most appropriate muscle for obtaining the fiducial point, to distinguish the myoclonic discharges from the background EMG activities, and to avoid artifacts such as head movements. When the myoclonic jerks occur infrequently in the resting condition, passive or active movement of the corresponding limb might help increase the number of jerks. In case of hand myoclonus, the positive peak or the onset of the negative peak of the EEG spike precedes the myoclonus by 20 milliseconds, on average, and it is localized to the central region of the contralateral head.

SEPs are recorded by stimulating the median nerve at wrist by electric shock of 0.2 to 0.3 milliseconds duration with the stimulus intensity 10% above the motor threshold delivered at a frequency of 1 Hz. Averaging of 100 sweeps is usually sufficient, but it is important to confirm the reproducibility of the results. The initial peak of the cortical SEP, N20/P20, is not significantly enlarged, but the subsequent peaks (P25, N30/P30, N35) are extremely enlarged in the majority of patients with cortical reflex myoclonus.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL

The rat model of posthypoxic myoclonus has been extensively studied by Truong’s group.5 They observed auditory stimulus-induced myoclonus in the rats that survived the acute stage of coma and seizures caused by mechanically induced cardiac arrest. The myoclonus was thought to be of brainstem origin, but in contrast to startle response, the acoustic reflex myoclonus did not show habituation. It was maximal about 4 days after the anoxic insult, and it subsided in 3 to 4 weeks.

TREATMENT

Symptomatic treatment of cortical myoclonus is achieved by anticonvulsants such as clonazepam, sodium valproate, and, on occasion, primidone to a variable degree, depending on the patient (Table 34-5). In addition, piracetam or levetiracetam may be effective for cortical myoclonus. This can be given either in combination with those anticonvulsants or alone. L-5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) has been reported to be effective, especially for posthypoxic myoclonus. Other forms of myoclonus also respond to clonazepam.

| Drug | Initial Dosage | Maintenance Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Clonazepam | 0.5-1.0 mg/day | 2-6 mg/day |

| Sodium valproate | 200 mg/day | 600-1200 mg/day |

| Piracetam | 12g/day | 12-21g/day |

| Levetiracetam | 1000 mg/day | 3000 mg/day |

| Primidone | 125 mg/day | 375-750 mg/day |

| L-5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) | 100 mg/day | 500-1500 mg/day |

Prepared with help from Dr. Akio Ikeda.

Caviness JN, Brown P. Myoclonus: current concepts and recent advances. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:598-607.

Lehesjoki A-E. Molecular background of progressive myoclonus epilepsy. EMBO J. 2003;22:3473-3478.

Shibasaki H, Hallett M. Electrophysiological studies of myoclonus. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:157-174.

Shibasaki Shibasaki H: Myoclonus and startle syndromes. In Jankovic J, Tolosa E, eds: Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. In press.

Truong DD, Kirby M, Kanthasamy A, et al. Posthypoxic myoclonus animal models. In: Fahn S, Frucht SJ, Truong DD, et al, editors. Advances in Neurology, vol 89: Myoclonus and Paroxysmal Dyskinesias. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:295-306.

1 Caviness JN, Brown P. Myoclonus: current concepts and recent advances. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:598-607.

2 Lehesjoki A-E. Molecular background of progressive myoclonus epilepsy. EMBO J. 2003;22:3473-3478.

3 Shibasaki H, Hallett M. Electrophysiological studies of myoclonus. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:157-174.

4 Shibasaki H: Myoclonus and startle syndromes. In Jankovic J, Tolosa E, eds: Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. In press.

5 Truong DD, Kirby M, Kanthasamy A, et al. Posthypoxic myoclonus animal models. In: Fahn S, Frucht SJ, Truong DD, et al, editors. Advances in Neurology, vol 89: Myoclonus and Paroxysmal Dyskinesias. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:295-306.