Chapter 215 Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Complications

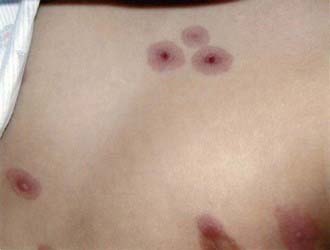

Complications are unusual. Despite the reportedly rare isolation of M. pneumoniae from nonrespiratory sites such as joints, pleural fluid, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the availability of PCR to detect specific segments of M. pneumoniae DNA has led to increasing identification of M. pneumoniae in nonrespiratory sites, particularly the central nervous system (CNS). Nonrespiratory illness can therefore involve direct invasion with M. pneumoniae or can involve autoimmune mechanisms, which is reflected by the frequency with which human antigens cross react with M. pneumoniae. Patients with or without respiratory symptoms can manifest illness involving the skin, CNS, blood, heart, gastrointestinal tract, and joints. Skin lesions include a variety of exanthemas, most notably maculopapular rashes, erythema multiforme, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). M. pneumoniae is the most common infectious agent identified as a cause of SJS, which usually develops 3-21 days after initial respiratory symptoms, lasts <14 days, and is rarely associated with severe complications (Figs. 215-1 and 215-2). M. pneumoniae has been linked to an atypical SJS with oral mucositis but absence of rash.

Figure 215-1 Lip changes found in Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection.

Atkinson TP, Balish MF, Waites KB. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathogenesis and laboratory detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:956-973.

Chig-Yung C, Chiang L-M, Chen T-P. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicated by necrotizing pneumonitis with massive pleural effusion. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:275-277.

Christie LJ, Honarmand S, Talkington DF, et al. Pediatric encephalitis: what is the role of Mycoplasma pneumoniae? Pediatrics. 2007;120:305-313.

Defilippi A, Silvestri M, Tacchella A. Epidemiology and clinical features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children. Resp Med. 2008;102:1762-1768.

Korppi M, Heiskanen-Kosma T, Kleemola M. Incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in children caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae: serological results of a prospective, population-based study in primary health care. Respirology. 2004;9:109-114.

Krause DC, Balish MF. Cellular engineering in a minimal microbe: structure and assembly of the terminal organelle of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:917-924.

Li X, Atkinson P, Hagood J, et al. Emerging macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumonia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:693-696.

Michelow IC, Olsen K, Lozano J, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:701-707.

Ravin KA, Rappaport LD, Zucherbraun NS, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a case series. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1002-e1005.

Waites KB, Talkington DF. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:697-728.

Walter ND, Grant GB, Bandy U, et al. Community outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: school-based cluster of neurologic disease associated with household transmission of respiratory illness. J Infect Dis. 2008;98:1365-1374.

Wang ND, Grant GB, Bandy U, et al. Community outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: school-based cluster of neurologic disease associated with household transmission of respiratory illness. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1365-1374.

Wang RS, Wang SY, Hsieh KS, et al. Necrotizing pneumonitis caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae in pediatric patients: report of five cases and review of literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:564-567.

Yang J, Hooper WC, Phillips DJ, et al. Cytokines in Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:157-168.