73 Myasthenia Gravis

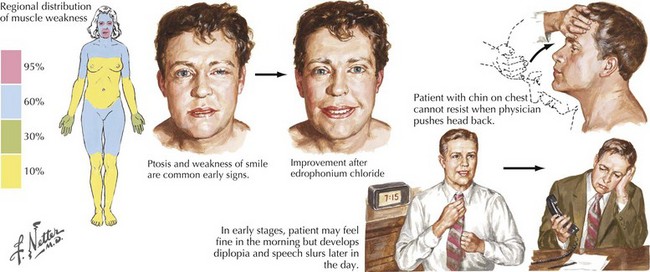

This vignette is typical of a myasthenia gravis (MG) patient with fatigable and fluctuating muscle weakness. MG almost always begins with ocular muscle weakness manifesting as ptosis, dysconjugate gaze, and eye closure weakness (Fig. 73-1). The symptoms of MG often spread to involve “bulbar” muscles, causing fatigable and fluctuating dysarthria, chewing weakness, and dysphagia. Respiratory, neck, and limb muscles can also become weak. An autoimmune basis for MG has been recognized since 1960. Overall, women are more commonly affected. Peaks of onset are seen in women in the second and third decades and for men in the fifth and sixth decades. The overall prevalence, estimated at 1 per 10,000, has increased over the past 40 years because of improved recognition, treatment, and survival.

Etiology And Pathogenesis

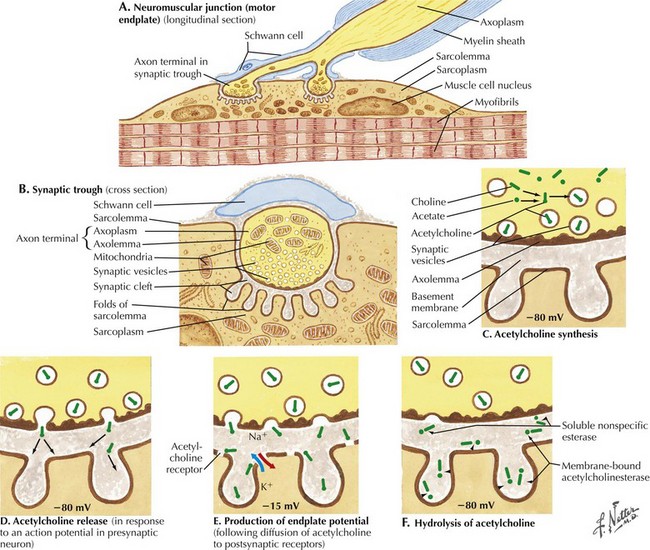

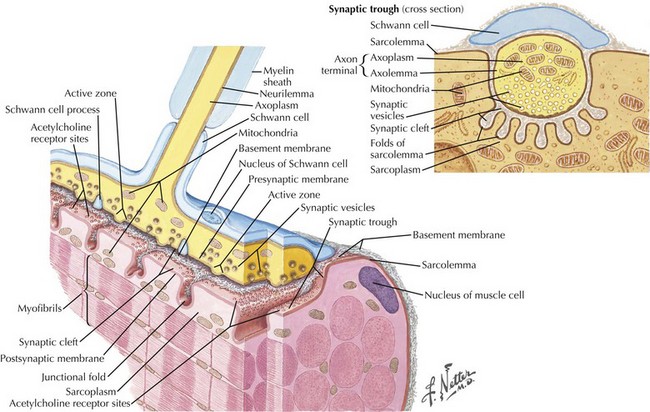

The most common cause of acquired MG is the abnormal development of antibodies to immunogenic regions (epitopes) on or around the nicotinic AChR of the postsynaptic endplate region at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) (Figs. 73-2 and 73-3). These AChR antibodies trigger immune-mediated degradation of the AChRs and their adjacent postsynaptic membrane. The loss of large numbers of functional AChRs decreases the number of muscle fibers that can depolarize during motor nerve terminal activation, resulting in a decreased generation of muscle fiber action potentials and subsequent muscle fiber contraction. Blocking of neuromuscular transmission causes clinical weakness when it affects large numbers of fibers.

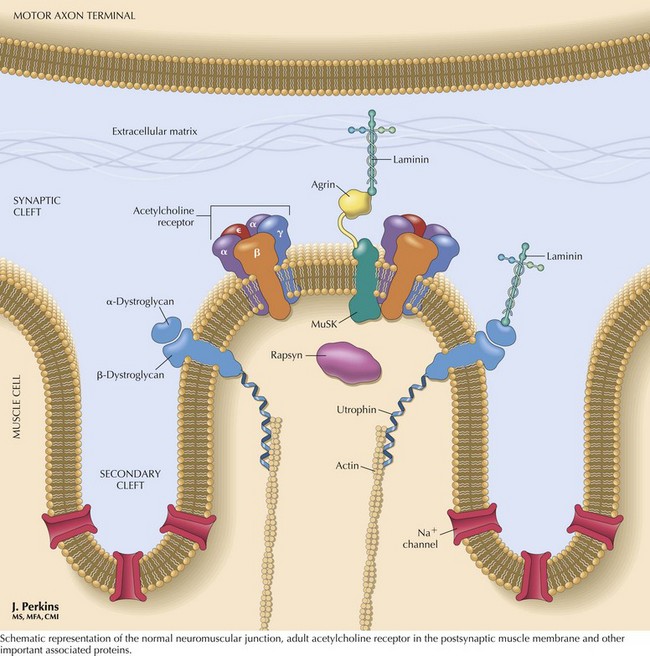

The nicotinic AChR contains five subunits arranged radially around a transmembrane ion channel (Fig. 73-4). The antibodies generated in MG are usually directed against the alpha subunit of the AChR. These antibodies may bind at or near the acetylcholine-binding site, directly preventing acetylcholine binding, or may alter receptor function through other mechanisms, such as increased receptor degradation or complement-mediated receptor lysis.

Clinical Presentation

Myasthenia gravis is typically classified as ocular, generalized, neonatal, congenital, or drug-induced. At presentation, weakness is confined to the ocular muscles in 80% of patients. Within 1–2 years, more generalized weakness develops in 85–90% of these individuals (see Fig. 73-1). In those few patients with primary ocular MG in whom bulbar or generalized weakness do not develop during the first 2 years, further progression to generalized MG is significantly less likely although it may occur as late as 8–10 years later (these patients are classified as having ocular MG).

Diagnostic Approach

The patient’s history and examination are the most important information directing one to a diagnosis of MG. Ancillary testing is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Assays for antibodies to AChR are positive in approximately 85% of patients with generalized MG. Individuals with purely ocular MG have an approximately 50% incidence of positive AChR antibodies. Another 7% of patients with generalized MG have antibodies to muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) (see Fig. 73-4). The remaining 8% of patients with generalized MG are classified as having “seronegative” generalized MG; that is, MG without a known accompanying autoantibody.

Computed tomographic or MR imaging of the mediastinum is an important diagnostic test in suspected MG. Ten to 15% of MG patients have thymomas; these may be benign (75–90%) or malignant thymic tumors (Fig. 73-5). Of those patients not having thymomas, 70% have thymic lymphoid follicular hyperplasia. Anti–striational muscle antibodies are present in 90% of patients with myasthenia and thymoma.

Management And Prognosis

Before the mid-1930s, there were no treatments for MG, and consequently the mortality rate for MG was approximately as high as 70%. The discovery and widespread use of anticholinesterase therapy (e.g., pyridostigmine) in the 1930s resulted in a dramatic reduction in mortality rate to approximately 30%. The anticholinesterase therapies work by decreasing the rate of breakdown of acetylcholine at the NMJ (Fig. 73-6). Pyridostigmine (e.g., Mestinon) is generally started at 30–60 mg orally every 6–8 hours. The dosage is titrated depending on the clinical response of the patient. Doses of more than 120 mg every 3–4 hours may cause cholinergic crisis, with paradoxically increased weakness (sometimes to a marked degree), increased salivation, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and muscle fasciculations. Anticholinesterase therapy, however, does not treat the basic pathophysiologic process (i.e., autoimmunity), and thus, most patients with generalized MG require some form of immunosuppressive therapy.

Briemberg HR. Neuromuscular diseases in pregnancy. Seminars Neurology. 2007;27:460-466.

Grob D, Brunner N, Namba T, Pagala M. Lifetime course of myasthenia gravis. Muscle and Nerve. 2008;37:141-149.

Hilton-Jones D. When the patient fails to respond to treatment: myasthenia gravis. Practical Neurol. 2007;7:405-411.

Luchanok U, Kaminski HJ. Ocular myasthenia: diagnostic and treatment recommendations and the evidence base. Current Opinions Neurol. 2008;21:8-15.

Mahadeva B, Phillips LH, Juel VC. Autoimmune disorders of neuromuscular transmission. Seminars in Neurology. 2008;28:212-227.