Chapter 31 MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN

General Discussion

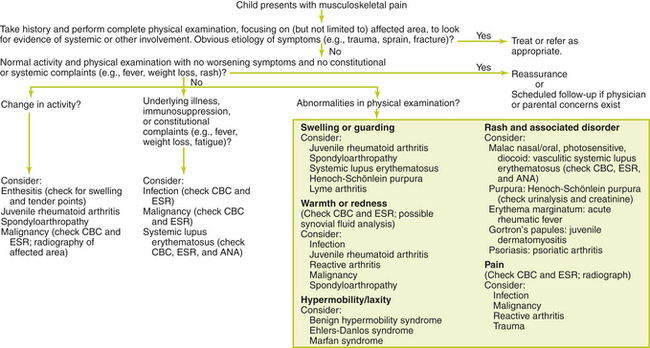

Musculoskeletal pain during childhood can be difficult for children to characterize. Most causes of acute musculoskeletal pain in children are easy to identify, but the cause of chronic musculoskeletal pain or pain that has associated systemic symptoms can be more difficult to diagnose (see Figure 31-1). Nonrheumatic causes of musculoskeletal pain are much more common than rheumatic causes.

Causes of Musculoskeletal Pain

Key Physical Findings

Suggested Work-up

| Complete blood count (CBC) | To evaluate for leukocytosis (infection, leukemia, or inflammatory conditions). White blood cells (WBCs) may be normal in up to 66% of children with leukemia in the initial evaluation of chronic joint pain. |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein | To evaluate for inflammation or infection. May be normal or elevated with arthritis. A discordant ESR and platelet count is worrisome for malignancy. |

| Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) | To evaluate for SLE, juvenile RA, and vasculitis. May be positive in up to 40% of healthy children. Titers greater than 1:320 are more likely to represent inflammatory diseases. |

| Rheumatoid factor | To evaluate for juvenile RA. 70% sensitivity and 82% specificity for RA, but has low positive predictive value in the primary care setting |

| Plain radiographs | May be helpful in diagnosing fractures, bone tumors, and chronic osteomyelitis |

| Blood culture | If an infectious etiology is suspected |

| Joint aspiration and examination of the synovial fluid (cell count and differential, gram stain, glucose, protein, aerobic and anaerobic cultures) | For a child with monoarthritis, who should be considered to have septic arthritis until it is ruled out |

Additional Work-up

| Lactate dehydrogenase | May be helpful when malignancy is suspected as elevated levels may indicate malignancy |

| Antistreptolysin-O (ASO) titer | If a recent streptococcal infection is suspected as the cause of arthritis |

| Lyme antibody titer | If Lyme disease is suspected |

| Anti-double-stranded DNA | To evaluate for SLE |

| HLA-B27 genotype | May be useful in the diagnosis of spondyloarthropathy. Should be considered if there is a family history of inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, or spondyloarthropathy. |

| cANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody) | To confirm a diagnosis of Wegener granulomatosis |

| Urinalysis and creatinine | If Henoch-Schönlein purpura is suspected |

| Synovial biopsy | May be necessary for the child with chronic monoarticular joint pain in whom a definitive diagnosis cannot be made after a thorough evaluation |

| Computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | May be helpful in diagnosing malignancy, inflammatory conditions, and cartilage abnormalities |

| Technetium bone scan | May be helpful in differentiating septic arthritis from osteomyelitis. May also be useful when the source of the patient’s pain is not clear after the clinical examination and initial evaluation. |

| Ultrasonography | May be useful in identifying and quantifying a joint effusion, especially in deeper joints such as the hips. Also may be used to guide needle aspiration of these joints. |

| Echocardiography | If pericarditis or carditis is suspected |

1. Babyn P., Doria A.S. Radiologic investigation of rheumatic diseases. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:373–411.

2. Frank G., Mahoney H.M., Eppes S.C. Musculoskeletal infections in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:1083–1106.

3. Frick S.L. Evaluation of the child who has hip pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37:133–140.

4. Gutierrez K. Bone and joint infections in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:779–794.

5. Junnila J.L., Cartwright V.W. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in children: Part I: initial evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:115–122.

6. Junnila J.L., Cartwright V.W. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in children: Part II: rheumatic causes. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:115–122.

7. Ravelli A., Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767–778.

8. Tuten H.R., Gabos P.G., Kumar S.J., Harter G.D. The limping child: a manifestation of acute leukemia. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:625–629.