Musculoskeletal disorders

Features of musculoskeletal disorders in children are:

• Although musculoskeletal presentations are common and often benign and self-limiting, they can be caused by a serious underlying condition such as infection, malignancy or non-accidental injury

• Many concerns of parents about their children’s posture are variations of normal alignment in the growing skeleton

• Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common cause of chronic arthritis in children.

Assessment of the musculoskeletal system

This should, as a minimum, include the pGALS (paediatric Gait, Arms, Legs, Spine) screen (see p. 25) to identify and localise musculoskeletal problems; any suggestion of a musculoskeletal problem should be followed by more detailed regional musculoskeletal examination (called pREMS, see p. 26).

Variations of normal posture

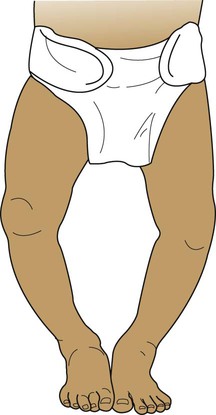

Bow legs (genu varum)

The normal toddler has a broad base gait. Many children evolve leg alignment with initially a degree of bowing of the tibiae, causing the knees to be wide apart – best observed while the child is standing with the feet together (Fig. 26.1). A pathological cause of bow legs is rickets; check for the presence of other clinical features (see Ch. 11). Severe progressive and often unilateral bow legs is a feature of Blount disease (infantile tibia vara), an uncommon condition predominantly seen in Afro-Caribbean children. Radiographs are characteristic with beaking of the proximal medial tibial epiphysis.

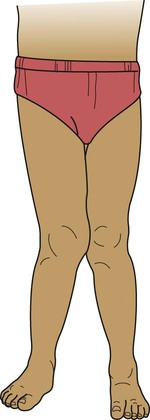

Flat feet (pes planus)

Toddlers learning to walk usually have flat feet due to flatness of the medial longitudinal arch and the presence of a fat pad which disappears as the child gets older (Fig. 26.3). An arch can usually be demonstrated on standing on tiptoe or by passively extending the big toe. Marked flat feet is common in hypermobility. A fixed flat foot, often painful, presenting in older children, may indicate a congenital tarsal coalition and requires an orthopaedic opinion. Symptomatic flat feet are often helped with footwear advice and, occasionally, an arch support may be required.

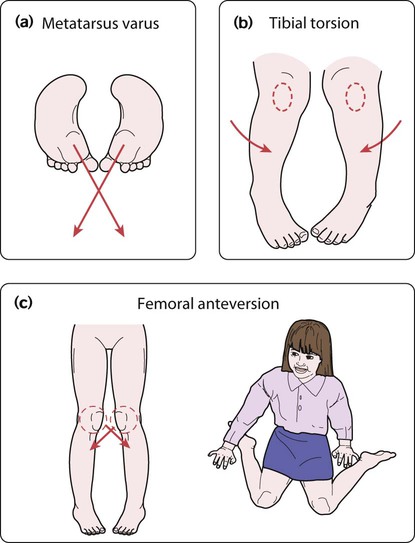

In-toeing and out-toeing

There are three main causes of in-toeing:

• Metatarsus varus (Fig. 26.4a) – an adduction deformity of a highly mobile forefoot

• Medial tibial torsion (Fig. 26.4b) – at the lower leg, when the tibia is laterally rotated less than normal in relation to the femur

• Persistent anteversion of the femoral neck (Fig. 26.4c) – at the hip, when the femoral neck is twisted forward more than normal.

The clinical features are described in Box 26.1.

Out-toeing is uncommon but may occur in infants between 6 and 12 months of age.

When bilateral, it is often due to lateral rotation of the hips and resolves spontaneously.

Abnormal posture

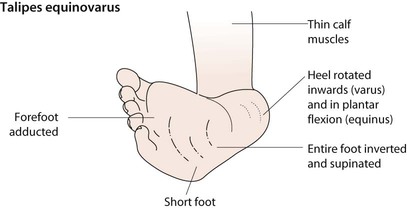

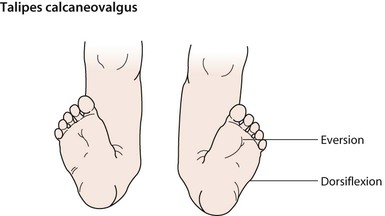

Talipes equinovarus (clubfoot)

Talipes equinovarus is a complex abnormality (Figs 26.5, 26.6). The entire foot is inverted and supinated, the forefoot adducted and the heel is rotated inwards and in plantar flexion. The affected foot is shorter and the calf muscles thinner than normal. The position of the foot is fixed, cannot be corrected completely and is often bilateral. The birth prevalence is 1 per 1000 live births, affects predominantly males (2 : 1), can be familial and is usually idiopathic. However, it may also be secondary to oligohydramnios during pregnancy, a feature of a malformation syndrome or of a neuromuscular disorder such as spina bifida. There is an association with developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH).

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

This is a spectrum of disorders ranging from dysplasia to subluxation through to frank dislocation of the hip. Early detection is important as it usually responds to conservative treatment; late diagnosis is usually associated with hip dysplasia, which requires complex treatment often including surgery. Neonatal screening is performed as part of the routine examination of the newborn (see Fig. 9.15), checking if the hip can be dislocated posteriorly out of the acetabulum (Barlow manoeuvre) or can be relocated back into the acetabulum on abduction (Ortolani manoeuvre). These tests are repeated at routine surveillance at 8 weeks of age. Thereafter, presentation of the condition is usually with a limp or abnormal gait. It may be identified from asymmetry of skinfolds around the hip, limited abduction of the hip or shortening of the affected leg.

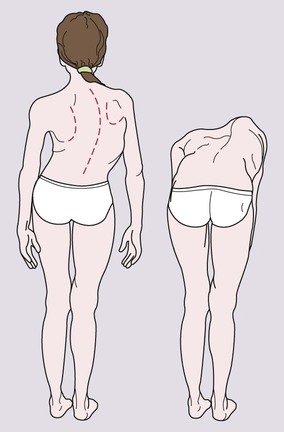

Scoliosis

Scoliosis is a lateral curvature in the frontal plane of the spine.

• Idiopathic. The most common, either early onset (<5 years old) or, most often, late onset, mainly girls 10–14 years of age during their pubertal growth spurt

• Congenital. From a congenital structural defect of the spine, e.g. hemivertebra, spina bifida, syndromes (e.g. VACTERL association – Vertebral, Anorectal, Cardiac, Tracheo-oEsophageal, Renal and Limb anomalies).

• Secondary. Related to other disorders such as neuromuscular imbalance (e.g. cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy); disorders of bone such as neurofibromatosis or of connective tissues such as Marfan syndrome, or leg length discrepancy, e.g. due to arthritis of one knee in JIA.

Examination should start with inspection of the child’s back while standing up straight. In mild scoliosis, there may be irregular skin creases and difference in shoulder height. The scoliosis can be identified on examining the child’s back when bent forward (Fig. 26.8). If the scoliosis disappears on forward bending, it is postural although leg lengths should be checked.

The painful limb, knee and back

Hypermobility

Older children or adolescents with hypermobility may complain of musculoskeletal pain mainly confined to the lower limbs, often worse after exercise. Joint swelling is usually absent or is transient. Hypermobility may be generalised or limited to peripheral joints (such as hands and feet). There is symmetrical hyperextension of the thumbs and fingers that can be hyperextended onto the forearms (Fig. 26.9), elbows and knees can be hyperextended beyond 10°, and palms can be placed flat on the floor with knees straight. Lower limb findings associated with hypermobility are hyperextensibility of the knee joint and flat feet with normal arches on tiptoe, which are over-pronated secondary to ankle hypermobility.

Acute-onset limb pain

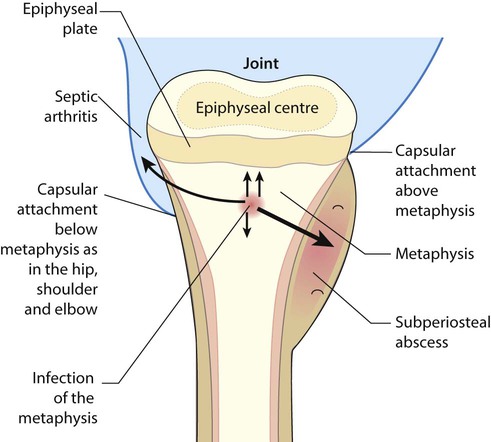

Osteomyelitis

In osteomyelitis, there is infection of the metaphysis of long bones. The most common sites are the distal femur and proximal tibia, but any bone may be affected (Fig. 26.10). It is usually due to haematogenous spread of the pathogen, but may arise by direct spread from an infected wound. The skin is swollen directly over the affected site. Where the joint capsule is inserted distal to the epiphyseal plate, as in the hip, osteomyelitis may spread to cause septic arthritis. Most infections are caused by Staphylococcus aureus, but other pathogens include Streptococcus and Haemophilus influenzae if not immunised. In sickle cell anaemia, there is an increased risk of staphylococcal and salmonella osteomyelitis. Infection may be from tuberculosis; although rare in the UK, it needs to be considered, especially in the immunodeficient child.

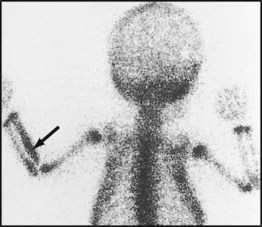

Investigation

Blood cultures are usually positive and the white blood count and acute-phase reactants are raised. X-rays are initially normal, other than showing soft tissue swelling; it takes 7–10 days for subperiosteal new bone formation and localised bone rarefaction to become visible. Ultrasound may show periosteal elevation at presentation. MRI allows identification of infection in the bone (subperiosteal pus and purulent debris in the bone) and differentiation of bone from soft tissue infection. Radionuclide bone scan (Fig. 26.11) may be helpful if the site of infection is unclear. The X-ray changes of chronic osteomyelitis are shown in Figure 26.12.

Limp

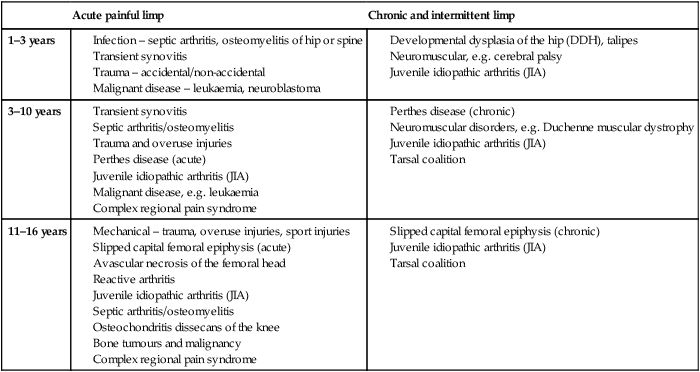

Limp can be divided into acute painful limp and chronic or intermittent limp, where pain may or may not be the presenting feature, and by age (Table 26.1).

Table 26.1

| Acute painful limp | Chronic and intermittent limp | |

| 1–3 years |

Transient synovitis (‘irritable hip’)

It can be difficult to differentiate transient synovitis from early septic arthritis of the hip joint (Table 26.2), and if there is any suspicion of septic arthritis, joint aspiration and blood cultures are mandatory.

Table 26.2

Contrast in clinical features of transient synovitis and septic arthritis of the hip

| Transient synovitis | Septic arthritis | |

| Onset | Acute limp, non-weight bearing | Acute onset, non-weight bearing |

| Fever | Mild/absent | Moderate/high |

| Child’s appearance | Child often looks well | Child looks ill |

| Hip movement | Comfortable at rest, limited internal rotation and pain on movement | Hip held flexed; severe pain at rest and worse on any attempt to move joint |

| White cell count | Normal | Normal/high |

| Acute-phase reactant/ESR | Slight increase/normal | Raised |

| Ultrasound | Fluid in joint | Fluid in joint |

| Radiograph | Normal | Normal/widened joint space |

| Management | Rest, analgesia | Joint aspiration, usually under ultrasound guidance Prolonged antibiotics, rest and analgesia |

| Course | Resolves <1 week, approx 3% develop Perthes disease | Progressive and severe joint damage if not treated |

Perthes disease

This is an avascular necrosis of the capital femoral epiphysis of the femoral head due to interruption of the blood supply, followed by revascularisation and reossification over 18–36 months. It mainly affects boys (male : female ratio of 5 : 1) of 5–10 years of age. Presentation is insidious, with the onset of a limp, or hip or knee pain. The condition may initially be mistaken for transient synovitis. It is bilateral in 10–20%. If suspected, X-ray of both hips (including frog views) should be requested; early signs of Perthes include increased density in the femoral head, which subsequently becomes fragmented and irregular (Fig. 26.13).

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE)

Results in displacement of the epiphysis of the femoral head postero-inferiorly requiring prompt treatment in order to prevent avascular necrosis. It is most common at 10–15 years of age during the adolescent growth spurt, particularly in obese boys and is bilateral in 20%. There is an association with metabolic endocrine abnormalities, e.g. hypothyroidism and hypogonadism. Presentation is with a limp or hip pain, which may be referred to the knee. The onset may be acute, following minor trauma or insidious. Examination shows restricted abduction and internal rotation of the hip. Diagnosis is confirmed on X-ray (Fig. 26.14), and a frog lateral view should also be requested. Management is surgical, usually with pin fixation in situ.

Arthritis

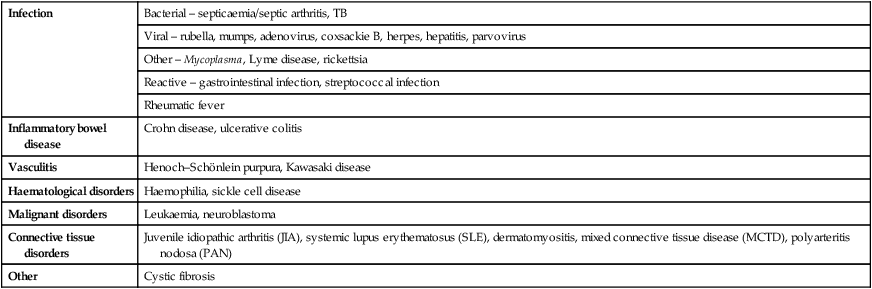

The causes of polyarthritis are listed in Table 26.3.

Table 26.3

| Infection | Bacterial – septicaemia/septic arthritis, TB |

| Viral – rubella, mumps, adenovirus, coxsackie B, herpes, hepatitis, parvovirus | |

| Other – Mycoplasma, Lyme disease, rickettsia | |

| Reactive – gastrointestinal infection, streptococcal infection | |

| Rheumatic fever | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis |

| Vasculitis | Henoch–Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease |

| Haematological disorders | Haemophilia, sickle cell disease |

| Malignant disorders | Leukaemia, neuroblastoma |

| Connective tissue disorders | Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis, mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) |

| Other | Cystic fibrosis |

Septic arthritis

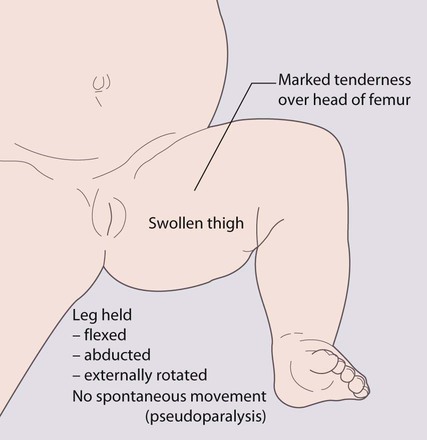

Presentation

This is usually with an erythematous, warm, acutely tender joint, with a reduced range of movement, in an acutely unwell, febrile child. Infants often hold the limb still (pseudoparesis, pseudoparalysis) and cry if it is moved. A joint effusion may be detectable in peripheral joints. In osteomyelitis, although a sympathetic joint effusion may be present, the tenderness is over the bone, but in up to 15% there is coexistent septic arthritis. The diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip can be particularly difficult in toddlers, as the joint is well covered by subcutaneous fat (Fig. 26.15). Initial presentation may be with a limp or pain referred to the knee.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)

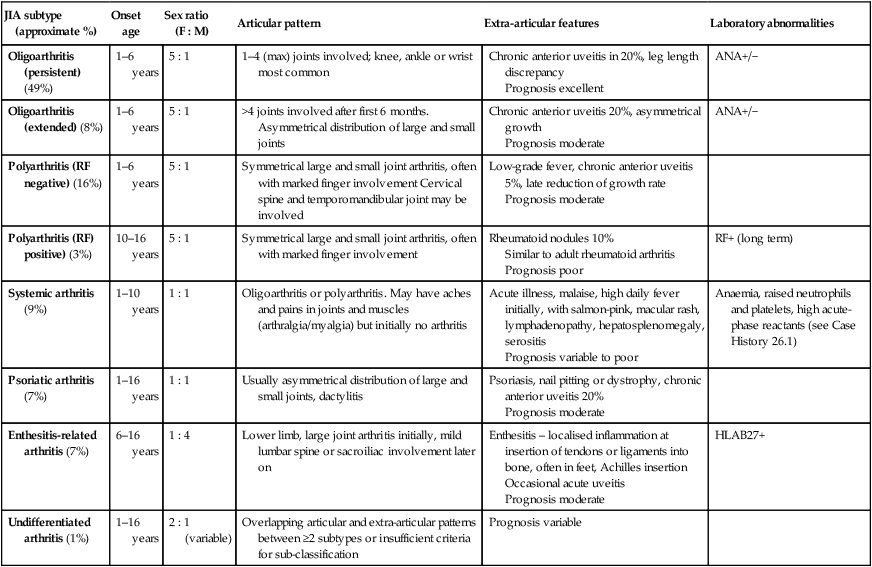

There are at least seven different subtypes of JIA. Its classification is clinical and based on the number of joints affected in the first 6 months, as polyarthritis (more than four joints) (Fig. 26.16) and oligoarthritis (up to and including four joints) or systemic (with fever and rash). Psoriatic arthritis and enthesitis are further subtypes. Subtyping is further classified according to the presence of rheumatoid factor and HLA B27 tissue type. The subtypes and their clinical features are shown in Table 26.4.

Table 26.4

Classification and clinical features of JIA (juvenile idiopathic arthritis)

| JIA subtype (approximate %) | Onset age | Sex ratio (F : M) | Articular pattern | Extra-articular features | Laboratory abnormalities |

| Oligoarthritis (persistent) (49%) | 1–6 years | 5 : 1 | 1–4 (max) joints involved; knee, ankle or wrist most common | Chronic anterior uveitis in 20%, leg length discrepancy Prognosis excellent |

ANA+/− |

| Oligoarthritis (extended) (8%) | 1–6 years | 5 : 1 | >4 joints involved after first 6 months. Asymmetrical distribution of large and small joints | Chronic anterior uveitis 20%, asymmetrical growth Prognosis moderate |

ANA+/− |

| Polyarthritis (RF negative) (16%) | 1–6 years | 5 : 1 | Symmetrical large and small joint arthritis, often with marked finger involvement Cervical spine and temporomandibular joint may be involved | Low-grade fever, chronic anterior uveitis 5%, late reduction of growth rate Prognosis moderate |

|

| Polyarthritis (RF) positive) (3%) | 10–16 years | 5 : 1 | Symmetrical large and small joint arthritis, often with marked finger involvement | Rheumatoid nodules 10% Similar to adult rheumatoid arthritis Prognosis poor |

RF+ (long term) |

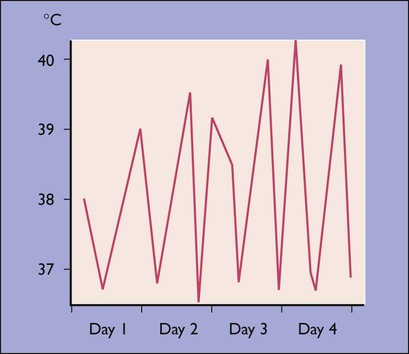

| Systemic arthritis (9%) | 1–10 years | 1 : 1 | Oligoarthritis or polyarthritis. May have aches and pains in joints and muscles (arthralgia/myalgia) but initially no arthritis | Acute illness, malaise, high daily fever initially, with salmon-pink, macular rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, serositis Prognosis variable to poor |

Anaemia, raised neutrophils and platelets, high acute-phase reactants (see Case History 26.1) |

| Psoriatic arthritis (7%) | 1–16 years | 1 : 1 | Usually asymmetrical distribution of large and small joints, dactylitis | Psoriasis, nail pitting or dystrophy, chronic anterior uveitis 20% Prognosis moderate |

|

| Enthesitis-related arthritis (7%) | 6–16 years | 1 : 4 | Lower limb, large joint arthritis initially, mild lumbar spine or sacroiliac involvement later on | Enthesitis – localised inflammation at insertion of tendons or ligaments into bone, often in feet, Achilles insertion Occasional acute uveitis Prognosis moderate |

HLAB27+ |

| Undifferentiated arthritis (1%) | 1–16 years | 2 : 1 (variable) | Overlapping articular and extra-articular patterns between ≥2 subtypes or insufficient criteria for sub-classification | Prognosis variable |

If systemic features are present, sepsis and malignancy must always be considered.

Complications

Growth failure

This may be generalised from anorexia, chronic disease and systemic corticosteroid therapy (Fig. 26.17). May also be localised overgrowth such as leg length discrepancy due to prolonged active knee synovitis and undergrowth, such as micrognathia, usually seen in long-standing or suboptimally treated arthritis due to premature fusion of epiphyses.

Management

• NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and analgesics – do not modify disease but help relieve symptoms during flares

• Joint injections, increasingly under ultrasound guidance – effective, first-line treatment for oligoarticular JIA; in polyarticular disease multiple joint injections are used as bridging agent when starting methotrexate. Often requires sedation or inhaled anaesthesia (Entonox)

• Methotrexate – early use reduces joint damage. Effective in approximately 70% with polyarthritis, less effective in systemic features of JIA. It is given as weekly dose (tablet, liquid or injection) and regular blood monitoring is required (for abnormal liver function and bone-marrow suppression). Nausea is common.

• Systemic corticosteroids – avoided if possible, to minimise risk of growth suppression and osteoporosis. Pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone often used for severe polyarthritis as an induction agent. May be life-saving for severe systemic arthritis or macrophage activation syndrome.

• Cytokine modulators (‘biologics’) and other immunotherapies – Many agents (e.g. anti-TNF alpha, IL-1, CTLA-4 or IL-6) now available and useful in severe disease refractory to methotrexate. Costly and given under strict national guidance with registries for long-term surveillance. T-cell depletion coupled with autologous haematopoetic stem cell rescue (bone marrow transplant) is an option for refractory disease.

Juvenile dermatomyositis

Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDMS) is rare. It usually begins insidiously with malaise, progressive weakness (often difficulty climbing stairs) and facial rash with erythema over the bridge of the nose and malar areas and a violaceous (heliotropic) discoloration of the eyelids (see Fig. 27.10). The skin over the metacarpal and proximal interphalangeal joints may be hypertrophic and pink, and the nailfold capillaries may be dilated and tortuous. Muscle pain is a common, if non-specific, symptom and arthritis is present in 30%. Respiratory failure and aspiration pneumonia may be life-threatening. The condition is described further in Chapter 27.

Genetic skeletal conditions

Achondroplasia

Inheritance is autosomal dominant, but about 50% are new mutations. Clinical features are short stature from marked shortening of the limbs, a large head, frontal bossing and depression of the nasal bridge (see Fig. 11.10). The hands are short and broad. A marked lumbar lordosis develops. Hydrocephalus sometimes occurs.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (brittle bone disease)

In the most common form (type I), which is autosomal dominant, there are fractures during childhood (Fig. 26.19a) and a blue appearance to the sclerae (Fig. 26.19b) and some develop hearing loss. Treatment with bisphosphonates reduces fracture rates. The prognosis is variable. Fractures require splinting to minimise joint deformity.

There is a severe, lethal form (type II) with multiple fractures already present before birth (Fig. 26.20). Many affected infants are stillborn. Inheritance is variable but mostly autosomal dominant or due to new mutations. In other types, scleral discoloration may be minimal.