Muscle disease

Primary muscle disease is relatively uncommon (prevalence 12 per 100 000) and may be inherited or acquired. This is an area in neurology where the recent rapid developments in molecular genetics are providing new insights into the molecular basis of muscle disease. This is also leading to developments in the classification of muscle disease, for example the channelopathies.

Inherited diseases include the following:

Progressive muscular dystrophies causing progressive weakness. The patterns of inheritance, age of onset, patterns of muscular involvement and prognoses differ according to type.

Progressive muscular dystrophies causing progressive weakness. The patterns of inheritance, age of onset, patterns of muscular involvement and prognoses differ according to type. Metabolic myopathies may produce progressive deficits, e.g. most mitochondrial myopathies, or intermittent, particularly exertional symptoms, e.g. McArdle’s disease.

Metabolic myopathies may produce progressive deficits, e.g. most mitochondrial myopathies, or intermittent, particularly exertional symptoms, e.g. McArdle’s disease. Non-progressive congenital myopathies present at various ages and may be mild to severe. Examples include central core, myotubular and nemaline myopathies. All are rare.

Non-progressive congenital myopathies present at various ages and may be mild to severe. Examples include central core, myotubular and nemaline myopathies. All are rare. Myotonic syndromes are characterized by impaired muscle relaxation after contraction, sometimes with muscle weakness.

Myotonic syndromes are characterized by impaired muscle relaxation after contraction, sometimes with muscle weakness. Syndromes of episodic weakness or periodic paralysis due to disorders of ion channels in the muscle membranes.

Syndromes of episodic weakness or periodic paralysis due to disorders of ion channels in the muscle membranes.Muscular dystrophies

Boys with DMD develop weakness of the lower limb girdle by the age of 3–6 years. They adopt the Gower manoeuvre to rise from lying (Fig. 1). Weakness then spreads to other muscle groups in the legs and arms. There may be characteristic rubbery enlargement (pseudohypertrophy) of the calf muscles and 30% have a low IQ. Untreated, most are wheelchair-bound by the age of 12 years and die from respiratory complications by the age of 25 years.

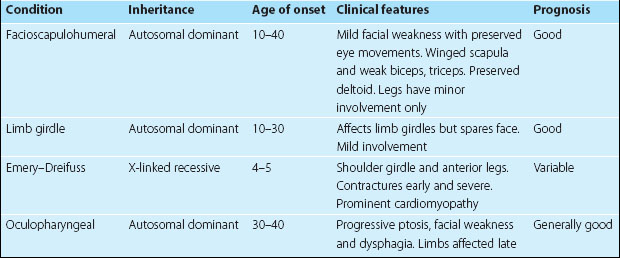

Investigations include muscle creatine kinase (CK), which is highly elevated, and muscle biopsy, which shows no fibres staining for dystrophin. An ECG is often abnormal. Treatment is supportive, especially prevention of complications, including respiratory infection and contractures. Steroids may slow the progression and respiratory support can prolong survival. Genetic treatments and stem cell implants have yet to provide benefit. BMD follows a milder course with an onset at age 5–45 years; there is also calf pseudohypertrophy and a highly elevated CK, 20–200 times normal. Other dystrophies are described in Table 1; some have been identified as affecting proteins closely linked with dystrophin.

Metabolic myopathies

Myotonic syndromes

Dystrophia myotonica is the most common cause (prevalence 2 per 100 000). It is an autosomal dominant disorder of a muscle protein kinase, with variable severity and age of onset and a progressive course, whose genetic basis has been elucidated recently. Patients present with muscle cramps triggered by cold, weakness of the hands or difficulty releasing their grip. There is a characteristic facial appearance with frontal balding, severe temporalis and sternomastoid muscle wasting, bilateral ptosis and facial weakness giving an expressionless, myopathic facies. Limb weakness is worst distally in the hands and feet and there is usually areflexia. The patient cannot suddenly open a clenched fist or release the hand from a handshake. Complications of myotonic dystrophy include cardiac conduction abnormalities and impaired respiratory drive, which may be life-threatening, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, cataracts, male infertility, bowel dysmotility and mental retardation. Myotonia may be improved by phenytoin, procainamide or quinine.

Acquired muscle disease

This usually presents with progressive proximal weakness. It is usually secondary to metabolic disturbance (Box 1), inflammatory disease, infection or toxins. Many are treatable.

Polymyositis

Polymyositis is the most common inflammatory muscle disease in adults (prevalence 6 per 100 000), especially in women aged 30–60 years. Proximal limb, trunk, neck, pharyngeal and oesophageal muscles may all be involved. The onset is usually subacute or chronic but occasionally acute. Muscles may be painful or tender. CK is usually markedly elevated and EMG often shows myopathic changes with increased spontaneous activity (p. 35). The diagnosis is confirmed by demonstrating inflammatory changes on muscle biopsy. Treatment is with corticosteroids and immunosuppression, most commonly with azathioprine. CK is a marker of disease activity to regulate treatment, which may be long term, and prognosis is good.

Dermatomyositis

This occurs mainly in children, in which similar myositis is combined with a purple ‘heliotrope’ rash around the eyes and a linear red rash over the knuckles and proximal phalanges: ‘Gottron’s papules’ (Fig. 2). Polymyositis and dermatomyositis may occur in isolation or as part of a more widespread collagen–vascular disease. Sarcoidosis or polyarteritis nodosa may produce a similar clinical picture. There is an increased relative risk of neoplasia in both polymyositis (9%) and dermatomyositis (15%) compared with the general population. Lymphoma and ovarian carcinoma are particularly associated.

Acute myopathy

This may be autoimmune, due to viral or parasitic infections, drugs, trauma, burns and snake venoms (see Box 1). There may be massive muscle damage with myoglobinaemia and myoglobinuria, causing acute renal tubular necrosis. Rhabdomyolisis may also occur after excessive muscle use: prolonged marches, status epilepticus and neuroleptic malignant syndrome (p. 121).