46 Multiple Sclerosis

Pathology

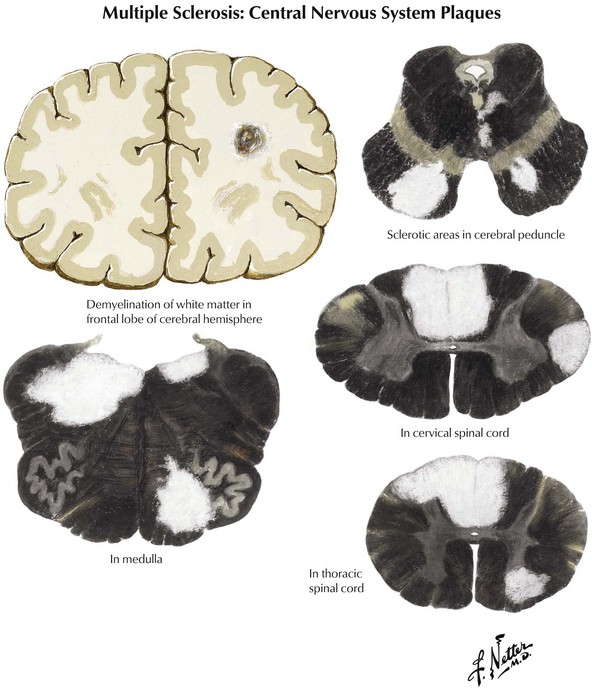

Coronal brain sections reveal changes similar to those noted on MRI, where variously sized MS plaques are apparent. Recently acquired lesions are pink and soft, whereas chronic MS lesions are gray, translucent, and firm (Fig. 46-1). It is often difficult to correlate the multiple lesions found at autopsy or by MRI throughout the neuraxis with a patient’s history. Sometimes classic MS plaques exist in patients who were never clinically suspected of harboring it.

Clinical Subtypes

Differential Diagnosis

Ocular

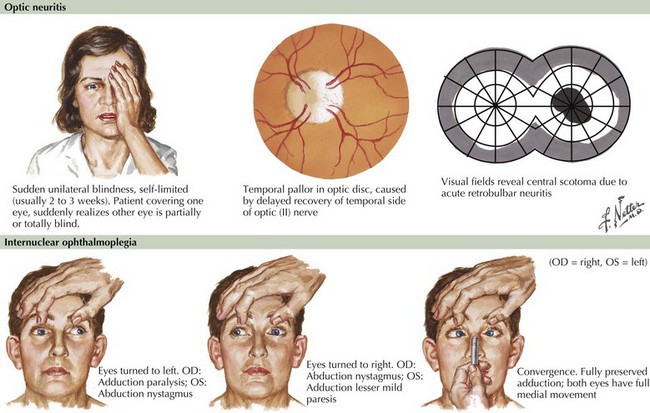

Blurred vision, likely a manifestation of acute optic neuritis, is a very common initial symptoms of MS. This may have great variability in degree from gross total unilateral blindness to a subtle change in visual acuity. Vision changes may also be related to a poorly expressed diplopia secondary to an INO, one of the most common neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations of MS (Fig. 46-2). In the first instance, the differential diagnosis includes any process affecting the retina or cornea, and in the second, the diplopia may be related to a pseudo-INO, mimicking MS. This is typical of myasthenia gravis. Sometimes a true INO secondary to a stroke may occur in older hypertensive patients.

When temporally associated with a myelopathy, this clinical presentation is referred to as Devic syndrome, or neuromyelitis optica (NMO). This is a humorally mediated autoimmune demyelinating disorder that is immunologically distinct from MS. It is characterized by an autoantibody that recognizes aquaporin 4 (AQP4), a water channel expressed on astrocyte podocytes. NMO may sometimes have a poorer prognosis than MS although on occasion it is more acutely responsive to immunosuppression or chemotherapy. This Devic syndrome does not typically benefit from first-line long-term MS disease modifiers (Chapter 47).

Inner Ear or Cerebellum

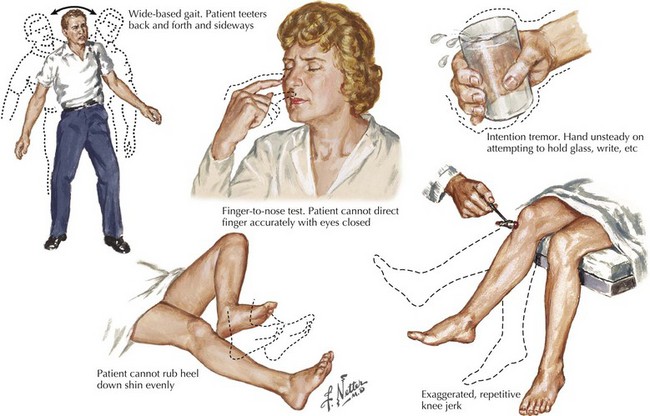

A vague feeling of unsteadiness, dizziness, and sometimes a whirling vertigo with nausea are frequent symptoms of MS. Precise definition of exactly what patients mean by “dizzy” is essential. Frequently, patients are in fact reporting a sense of dysequilibrium likely representing cerebellar dysfunction and less commonly reflecting vestibular pathways. Such patients typically demonstrate a broad-based gait, various signs of dysmetria, a tremor not seen in patients with a primary vestibular lesion, and often vertical nystagmus (Fig. 46-3).

Myelopathies

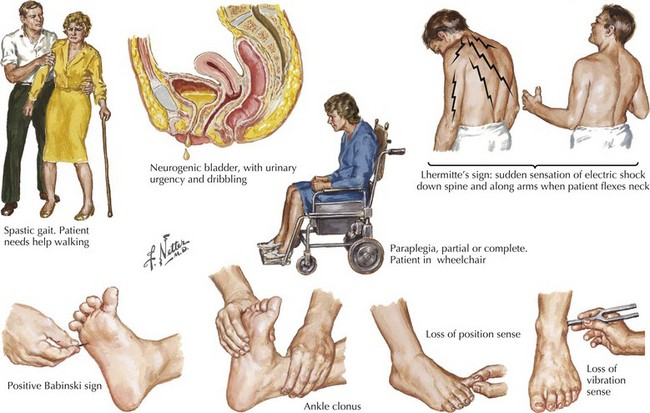

Sensations of tingling, tightness, pins and needles, and electric shocks are common MS symptoms. Relatively early in the disease course, some of these patients report an electric shock–like sensation that usually radiates down the back or arms, occurring spontaneously when the patient bends his or her neck. This is known as Lhermitte’s sign (Fig. 46-4). This most commonly occurs with MS patients but often the patient does not report this per se. Rather the skilled examiner is trained to ask about such as it is pathognomonic and indicative of spinal posterior column dysfunction. Lhermitte’s sign can be reported with almost any form of spinal cord disease, including spondylosis with significant cervical spinal stenosis, a space-occupying lesion, vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency, or copper deficiency syndromes, especially in individuals who have had major gastrectomies or unusual diets, such as excess zinc that blocks copper absorption.

Clinical Vignette

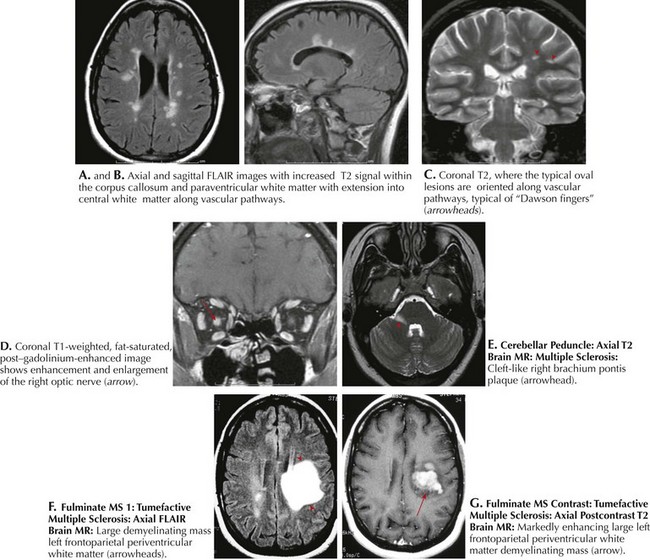

Occasionally an acute focal cerebral lesion may be the presenting sign of MS leading the clinician to suspect that the patient has a glioblastoma multiforme, the most malignant of brain tumors. Fortunately, stereotactic biopsy occasionally demonstrates a rare monofocal form of MS, monofocal acute inflammatory demyelination (MAID) (Fig. 46-5). This can mimic a primary brain tumor or abscess. It is a rare and unique demyelinating disorder that may herald, or be superimposed on, more typical MS or may be seemingly unassociated with MS. MAID usually affects the cerebral hemispheres, and its clinical and radiologic features suggest a brain tumor. In contrast, an acute myelitis or optic neuritis is a more common example of a monofocal demyelinating process. Patients with the “cerebral form” of demyelinating disease have symptoms atypical for MS, including an acute hemiplegia, hemisensory complaints, and visual field deficits. Less common symptoms include headaches, seizures, aphasia, an alteration in level of consciousness, and cognitive or psychiatric manifestations.

Rarely, patients with a similar acute clinical presentation have multifocal CNS lesions, diagnosed as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) (Chapter 47). ADEM usually has widespread or multifocal MRI abnormalities.

Neuromuscular Transmission Defects

Like MS, myasthenia gravis tends to occur in young women. It is characterized by combinations of intermittent visual difficulties, particularly diplopia often referred to by the patient as blurring, dysarthria, and fatigue, symptoms that also occur in MS. Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), a presynaptic autoimmune, often paraneoplastic, disorder, also may cause intermittent weakness, bulbar signs, and fatigue (Chapter 70), mimicking the fatigue or nonspecific tiredness that are so commonly presenting signs of MS.

Conversion Hysteria

All too often, patients eventually diagnosed with MS do not have any definitive findings on their initial neurologic examination. This often leads the initial and unsuspecting physician into a common and sad differential diagnostic error. One must take great care not to falsely apply diagnostic significance to various situational anxieties such as occupational stresses, marital discord, or financial worries as being emotional precipitants for ill-defined clinical presentations and suggest that the patient has a somatoform disorder (Chapter 26). Conversion hysteria must always be a diagnosis of exclusion. This relatively rare disorder frequently occurs in young adults, particularly women, within the setting of poorly articulated psychologic stress, sometimes related to sexual abuse such as incest.

Diagnostic Approach

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

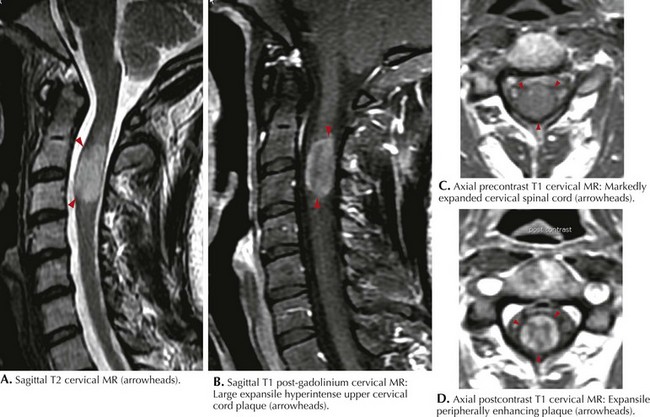

Classic MRI findings are typified by multiple well-demarcated ovoid plaques whose long axis are situated perpendicularly along callososeptal interfaces and demonstrate a perivenular extension within the corpus callosum (Dawson fingers). Furthermore, plaques have a propensity for the periventricular and subcortical white matter, middle cerebellar peduncle, pons, or medulla (see Fig. 46-5). Within the spinal cord per se, white matter lesions can involve any part of the many afferent or efferent tracts, particularly the dorsal columns. At times the lesion can be so large that it mimics an intramedullary tumor as characterized by a large expansile hyperintense upper cervical cord plaque as seen in Figure 46-6. MRI has unequivocally replaced CSF analysis, the oldest methodology, as well as various forms of evoked neurophysiologic potentials, as the primary diagnostic methodology.

MRI of the spinal cord may be particularly useful in substantiating a diagnosis (see Fig. 46-6). In clinically suspicious cases with normal or equivocal brain MRI, spinal cord lesions can be compelling, even without symptoms referable to the spinal cord. Spinal cord lesions, however, are sometimes not as easily identified because of the constraints of motion artifact. The increased availability of 3-Tesla magnets in the coming years will add further image refinement, particularly with primary spinal forms of MS.

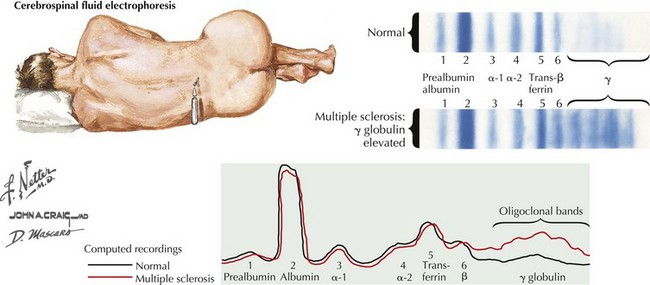

Cerebrospinal Fluid

The typical CSF profile of a patient with MS is summarized in Figure 46-7. The white blood cell count is typically normal, with less than 6 mononuclear cells/mm3 being present; however, occasionally one may see MS patients with up to 50 lymphocytes per cubic millimeter. This usually does not exceed 25 cells/mm3. Lymphocyte counts greater than 100/mm3 must arouse suspicion of other inflammatory or even neoplastic processes. Given the expectation of subtle, if any, pleocytosis, it is paramount to strive for an atraumatic tap. The number of cells present may correlate with enhancing MRI lesions and thus with disease activity. However, there is no apparent correlation between cell count and T2 lesion burden. The CSF glucose level is normal, appropriate to the generally benign cell counts.

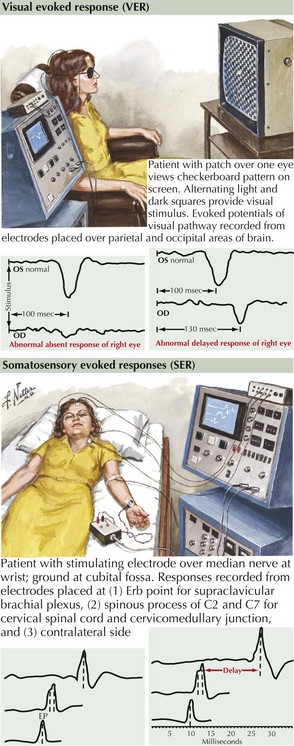

Evoked Potentials

With VERs, a peripheral stimulus, typically a reversing high-contrast checkerboard pattern, provides a means to study the integrity of the visual system. The response latencies can yield objective data regarding the ability of the nervous system to transmit impulses efficiently from the optic nerve to the occipital cortex. If there is a unilateral absence or delay, one can conclude that there is slowing in conduction between the retina and the optic chiasm (Fig. 46-8). This is typical for a unilateral optic neuritis. It is particularly helpful as even if the patient totally regains his or her vision, the remyelination is not perfect; thus a marker is left for future reference. When bilateral changes are present with the potentials delayed, attenuated, or blocked because of a prior instance of CNS demyelination, one cannot precisely localize the lesion to the optic nerve as the lesion could be any place in the visual pathway.

Multiple Sclerosis Diagnostic Criteria

Although MRI provides a superb diagnostic testing modality, it always needs to be accompanied by an appropriate clinical setting to make an unequivocal diagnosis of MS. Clinicians utilize a set of consensus criteria that continually evolve as new technological advances become available. Clinical history and examination were the mainstays of diagnosis in 1965 when Schumacher et al. issued the first widely used criteria for MS; these required that five of six of the conditions shown in Box 46-1 be met before making a clinically definite diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

These preserved the traditional requirement of multiple attacks of disease separated in time and space. Additionally, these new criteria provided for consideration of MRI and CSF findings when only one objective MRI lesion is found, only a single clinical attack has occurred, or when disease progression is insidious. The McDonald Diagnostic Criteria were revised in 2005 to incorporate the growing role of MR imaging for making a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis as well as to foster early treatment without sacrificing sensitivity and specificity (Box 46-2).

Box 46-2 McDonald Criteria for Diagnosis of MS

Management And Therapy

Comi G, Filippi M, Barkhof L, et al. Effect of early interferon treatment on conversion to definite multiple sclerosis: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1576-1582.

European Study Group on Interferon beta-1b in Secondary Progressive MS. Placebo-controlled multicentre randomized trial of interferon beta-1b in treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998;352:1491-1497.

Fletcher SG, Castro-Borrero W, Remington G, et al. Sexual dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis: a multidisciplinary approach to evaluation and management. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6:96-107. An important review of particular importance to any MS patient with spinal cord dysfunction

Goodin DS, Cohen BA, O’Connor P, et al. Assessment: the use of natalizumab (Tysabri) for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2008;71:766-773.

Guo S, Bozkaya D, Ward A, et al. Treating relapsing multiple sclerosis with subcutaneous versus intramuscular interferon-beta-1a: modelling the clinical and economic implications. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(1):39-53. This study provides a useful cost analysis comparing effectiveness of two of the most common preparations of interferon beta-a

Hartung HP. New cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after treatment with natalizumab. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:28-31.

Kappos L, Pohlman CH, Freedman MS, et al. Treatment with interferon beta 1-b delays conversion to clinically definite and McDonald MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. Neurology. 2006;67(7):1242-1249.

Kumar N, McEvoy K, Ahlskog JE. Myelopathy due to copper deficiency following gastrointestinal surgery. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1782-1785.

Lassmann H. Axonal and neuronal pathology in multiple sclerosis: What have we learnt from animal models. Exp Neurol. 2009 Oct 17. [Epub ahead of print]. A review of the increasingly recognized importance of axonal damage in the early pathophysiology of MS

Lovblad KO, Anzalone N, Dorfler A, et al. MR imaging in multiple sclerosis: review and recommendations for current practice. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009 Dec 17. Epub ahead of print

Pohlman CH, O’Connor PW, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(9):899-910.

Pohlman CH, Reingold SC, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(6):840-846.

Swanton JK, Fernando KT, Dalton CM, et al. Early MRI in optic neuritis: The risk for disability. Neurology. 2009;72:542-550. This is an important prospective analysis of the risk of development of clinically active MS among a cohort of newly diagnosed optic neuritis patients