CHAPTER 49 Multiple Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

Multiple meningiomas are defined as two or more meningiomas detected simultaneously at different intracranial locations in the same patient. While the incidence was initially reported as 1% to 2% of meningioma cases by Cushing and Eisenhardt, the figures increased to 10.5%1 with the clinical application of computed tomography (CT) and 20% with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).2 As multiplicity in meningiomas is not uncommon, multiple meningiomas not only offer a challenging clinical decision making process but also provide an invaluable opportunity in neuroscience to probe the mechanisms of tumorigenesis.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The “multiple meningiomas” concept can be traced back to 1889; Anfimov and Blumenau are credited for the first report on the presence of more than one meningioma in a patient without phacomatosis.3–5 In 1938, Cushing and Eisenhardt6 used the term “multiple meningiomas” to refer to “something more than one meningioma and less than a diffusion in the absence of stigmata of Von Recklinghausen’s disease.” Although this description was clear enough to differentiate “meningiomatosis” and “multiple meningiomas,” both terms have been used interchangeably.7 Discussions in the following years aimed mainly to establish a valid terminology to distinguish true multiplicity distinct from those associated with various other tumors in neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2).8–11 Insofar as the descriptions were based solely on clinical observations without radiologic and genetic support, it remained elusive whether true multiple meningiomas exist as a separate disease entity or represent one end of the spectrum of NF2.5 From then, technical advancements influenced the meningioma concept in several ways. The advent of modern neuroimaging has resulted in changing concepts for meningiomas in terms of treatment planning and assessment, natural course, and incidence. Multiple meningiomas, as mentioned earlier, have been detected in much higher proportions, and the same conceptual discussions regarding meningiomas in general began to appear from different centers. On the other hand, evolution of genetic studies extending to intracranial tumor biology led to meningiomas becoming an attractive subject for cytogenetic and molecular genetics analyses. Within this context, multiple meningiomas are expected to provide important insights into the mechanisms of meningioma tumorigenesis.12

PATHOGENESIS

Numerous publications have described alterations in the NF2 gene (both in patients with and without NF2), which predispose individuals to nervous system tumors, including schwannomas, meningiomas, and ependymomas.13–23 There are two rare familial conditions (NF2 and meningiomatosis), both inherited as autosomal-dominant traits, that predispose patients to developing meningiomas. Rarely, these tumors may occur after either low-dose radiotherapy, as was once administered for tinea capitis, or after high-dose radiotherapy for head and neck malignancies. In both instances, long delays of more than 10 years occur between the administration of radiotherapy and meningioma occurrence and, not infrequently, multifocal tumors develop.24–28

Apart from various triggering factors from trauma to radiation, there are enough data to accept that meningiomas occur due to gene-related alterations. Meningiomas were one of the first solid tumors in humans to be shown to have consistent chromosomal abnormalities. The first confirmed tumor-associated gene in meningioma is the NF2 gene located on chromosome 22q and 60% of sporadic meningiomas exhibit either mutations in NF2 or deletions in 22q.29 Deletions of the short arm of chromosome 1 are the second most frequent alteration detected on cytogenetic analysis of meningiomas, and abnormalities in other chromosomes and genes have also been implicated.12,30,31 Sporadic, NF2-associated, pediatric, and radiation-induced meningiomas all potentially having various genetic differences suggest that research on multiple meningiomas apart from those with NF2 can contribute to meningioma tumorigenesis and development.12 Current data indicate that meningioma initiation is closely linked to the inactivation of one or more members of the highly conserved protein 4.1 superfamily, including the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene product merlin/schwannomin, protein 4.IB (DAL-1) and protein 4.1R.32 Based on the cytogenetic and molecular genetic analyses on meningiomas, two mechanisms can be speculated for the development of multiple meningiomas. Either the tumors arise independently, or originate from a clonal population of common abnormal cells that then spread to other anatomic sites during their development.12,33 Polyclonal origin is supported by the findings that reveal different histologic subtypes and karyotypes in the same patient.34–36 On the other hand, convincing data also exist on monoclonal origin of multiple meningiomas. Stangl and colleagues,2 in their study on 12 cases of non-NF2 multiple meningioma cases, have demonstrated a majority of multiple meningiomas with NF2 gene mutations are of somatic and clonal origin; thus spread of tumor cells via cerebrospinal fluid is the most likely mechanism to account for the development of multiple meningiomas. Larson and colleagues,33 using polymerase chain reaction assays to detect the pattern of X chromosome inactivation, demonstrated 15 tumors resected in 4 patients with multiple meningiomas showed inactivation of the same X chromosome, suggesting that tumors arose from the same clone of cells.

PRESENTATION

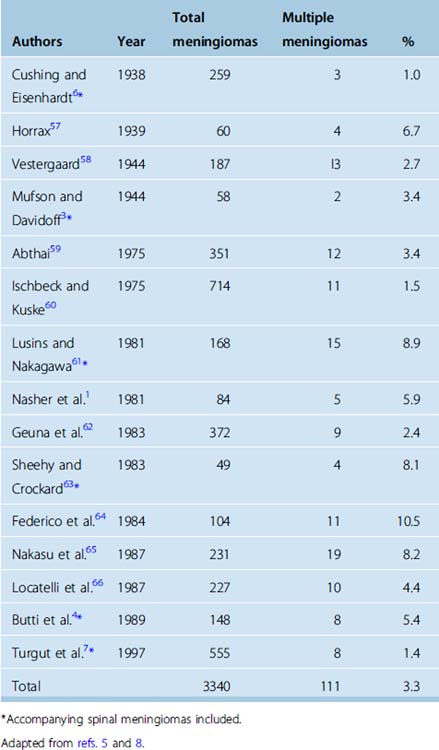

Before the introduction of modern neuroimaging technology, the incidence of multiple meningiomas was less than 2% in large series (Table 49-1). Most of the cases presented with signs and symptoms of a single intracranial tumor, due to the localization and the size, while the meningioma diagnosis would rely on the impression of the surgeon during surgery and finally on the histopathologic examination. Within these circumstances, multiplicity would be a concern only if associated meningiomas occurred in the vicinity of the primary tumor identified by the neurosurgeon. This scenario before the CT and MR era had several drawbacks. The reported incidence would be less than the actual, as “incidental” cases would be excluded. Those with locations distant from the primary symptomatic meningioma would also be elusive, as well demonstrated by Wood and colleagues37 in their 1957 monograph in which they reported a 16% incidence at autopsy. The lack of appropriate diagnosis from the beginning provoked another debate. Those detected within the vicinity after initial resection raise the question of recurrence, regrowth, or seeding versus unidentified multiplicity at the beginning. These speculations were resolved with modern neuroimaging; consecutive utilization of CT and MR in diagnosis brought the incidence of multiplicity to 20% in a recent series.2 Besides detection potential, MR especially enables better differentiation of meningiomatosis and NF2-associated disease from true multiple meningiomas.

The clinical presentation of meningiomas, as in all intracranial tumors, is dependent on tumor location. As with all slow-growing tumors, symptoms are usually subtle in nature and assumed to be long standing before a final diagnosis. Traditionally, a number of topographic anatomical tumor syndromes have been defined not necessarily specific to meningiomas.38 Review of the major published series on multiple meningiomas, most of them belonging to the CT era, do not distinguish any specific pathognomic features similar to single meningioma series.1,4,34,39 Most of the symptoms belong to a single meningioma specific to its’ size or localization rather than multiplicity. At present, easy access to highly specific noninvasive neuroimaging makes it possible to detect intracranial slow-growing masses such as meningiomas well before any long-lasting symptoms appear, unless focal symptoms such as seizure, diplopia, or tinnitus are the initial complaint. In this context, future series most probably will have much higher rates of both single or multiple meningiomas incidentally detected, compared to present series. Comparison of published patient data of meningioma series with multiple meningiomas reveals two major discrepancies. Multiple meningiomas are more common in females, and this predominance seems to be greater in multiple meningiomas than in meningiomas in general.7 Second, average age at presentation is younger in multiple meningioma cases.1,5,39 This might be suggestive for both indication of different genetic background of multiplicity, or simply unrecognized NF2 cases, misinterpreted as spontaneous meningiomas.

IMAGING

CT has been a revolutionary method in detecting multiple meningiomas and contributed greatly to present knowledge, probably more than to detection of single-mass lesions of the brain. Besides the obvious increase in the incidence of multiple meningiomas in published series after its introduction, CT has provided invaluable information in differentiating meningiomas from other multiple masses. Imaging of meningiomas via CT has several advantages compared to other intracranial masses; their specific, extra-axial localization and ultimate relationship to dura makes it possible to exclude most of the remaining mass lesions.38 In the presence of multiple mass lesions, the spectrum of disease is further reduced to metastatic disease, infection, or multicentric glial tumors where CT properties easy rule out the possibilities other than meningiomas. Nevertheless, CT has its limitations; small accompanying tumors, especially at the cranial base, may be overlooked in the presence of the primary tumor and multiplicity and meningiomatosis may be impossible to differentiate alone with CT scanning.1

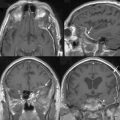

The gold standard in diagnosing, monitoring, and evaluating response to treatment of meningiomas is MR. Apart from diagnosis, ongoing research on different MR sequences aims to distinguish different structural pathologic variations contributing to biologic behavior. Signal properties, modes of enhancement, neighboring neural tissue reaction, vascularity of meningiomas have been subject to numerous articles and accumulating data along with advancing diagnostic capacity of MR technology will provide more accurate preoperative data on the behavior of different meningiomas.38,40 Unfortunately there have been no published data on MR characteristics of multiple meningiomas. Comparing preoperative data MR data to cytogenetic and molecular findings of multiple meningiomas may contribute to our knowledge on their origin and behavior.

PATHOLOGY

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), various pathologic subtypes of meningioma are compiled under a three-tiered system comprising three grades; meningioma, atypical meningioma, and anaplastic meningioma.31,38 The natural course and behavior of a given meningioma is currently believed to be dictated according to which grade it belongs, rather than its histopathologic subtype as well as the extent of resection. Although no significant correlation has been demonstrated between the histopathologic subtype and behavior, more aggressive characteristics have been displayed among special groups such as those with NF2 association, pediatric meningiomas and radiation induced meningiomas.31,41–44 On the other hand, limited data on the nonhereditary multiple meningioma cases fail to demonstrate any specific diversity in histopathologic distribution compared to ordinary meningiomas.7,34,38,45 In most of the published series, it has been acknowledged that multiple meningiomas are histologically benign and a poor prognosis is attributed to the higher number of surgical interventions and localization at critical areas rather than recurrences.1,4,11

DECISION MAKING IN MULTIPLE MENINGIOMAS

The best treatment option for a benign brain tumor is total removal without causing any morbidity. Intracranial meningiomas are no exception; craniotomy and removal of a meningioma and its dural base became the preferred treatment for symptomatic patients during the past 80 years.46 It has been well established that the amount of resection directly correlates with recurrence and outcome.47–49 Although a great proportion of meningiomas can be removed safely, attempted complete resection of some tumors either large or associated closely with critical neural or vascular structures may result with considerable morbidity and even mortality despite of advanced imaging and meticulous microsurgical techniques. The treatment strategy of the meningiomas has gone through a major transformation with accumulated data and evidence as well as advanced neuroimaging techniques. The generally benign nature of the disease weighed against the morbidity and altered quality of life with the attempted total resection has been one of the major dilemmas of neurologic surgery. Moreover, the increased amount of incidental meningiomas detected with advanced neuroimaging, when coupled with a relatively high number of asymptomatic meningiomas found at autopsy series, further raised questions on natural history and management of incidental meningiomas. Data from several studies exploring the growth rate of incidental meningiomas revealed 10% to 30% of the diagnoses were incidental and asymptomatic and 0 to 10% showed progression at an average follow-up of 6 months to 15 years, indicating many small incidentally discovered intracranial meningiomas may be observed expectantly.38 Eventually it is reasonable to accept each meningioma case as a separate disease with different natural history, different risks and thus requiring individual protocols for management.

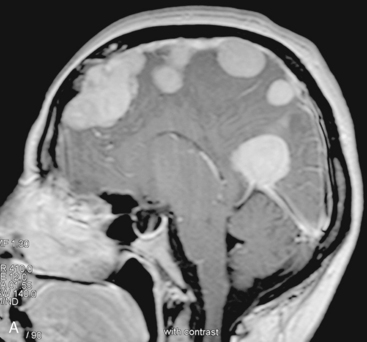

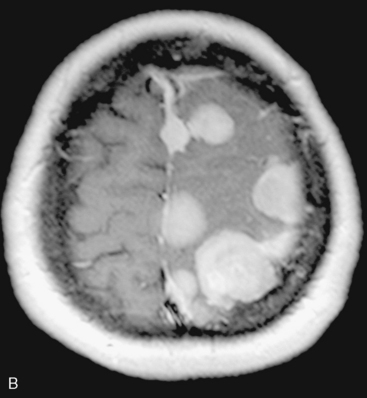

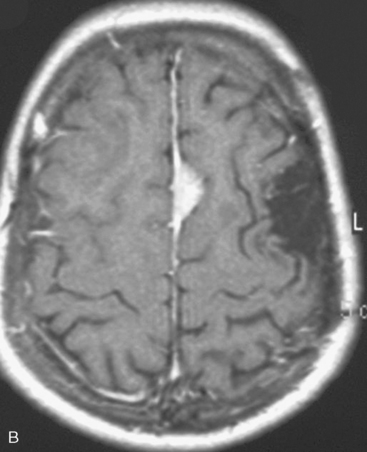

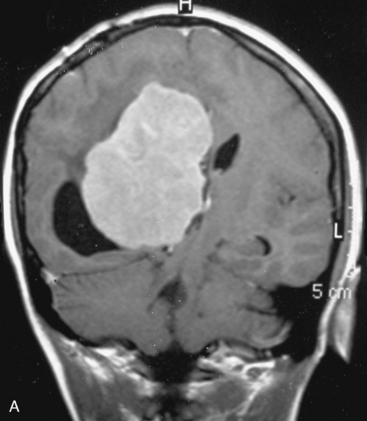

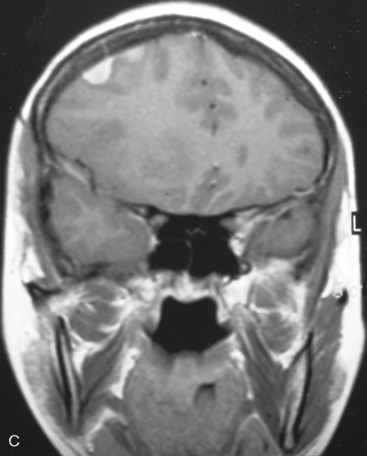

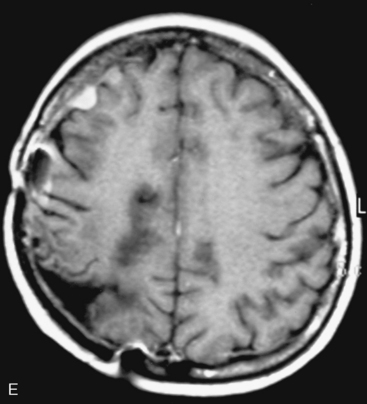

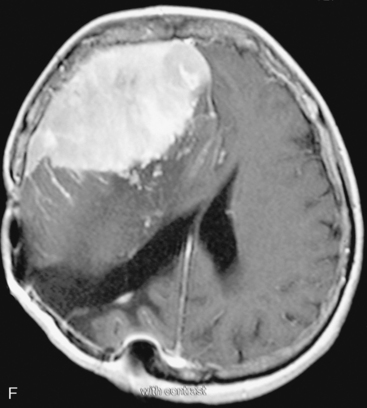

In the presence of multiplicity, it is rational to differentiate meningiomatosis and obvious NF2 cases as separate diseases, although it is not always possible to draw definitive borders with meningiomatosis and spontaneous multiple meningiomas despite advanced imaging and clinical information (Fig. 49-1). Moreover, in particular cases, it may be impossible to exclude the possibility of forme fruste NF2 from sporadic forms. It is not also clear how to consider meningiomas that appear at distant locations after primary excision of a single meningioma, whether they represent seeding from the primary focus or unidentified multiplicity at initial diagnosis. Apart from those with clinical genetical background like NF2 or meningiomatosis and a certain subset of cases with inconsistencies for definitive classification, there is no solid evidence that multiple meningiomas have behavior patterns distinct from single meningioma cases. It is also not very well established how to classify and approach various clinical presentations in case of multiplicity. As with single meningiomas, in most instances, multiple meningiomas are either diagnosed based on suspicion due to localization related symptoms or incidentally during neuroimaging. Especially, in those with remote localizations, the symptoms are most probably related to the meningioma which is either large, or close to vulnerable neural tissue like motor area, visual pathways, or cerebellopontine angle. The treatment algorithm is thus designed accordingly, the first step determining the meningioma responsible for the symptoms. The surgical decision is no different than for single meningiomas on that particular location. The decision of surgical intervention, apart from multiplicity, depends on age, medical condition, and tumor size and associated symptoms. Removal of the additional meningioma(s) should be reviewed separately, depending on the ease of access, and proximity to the primary lesion, all compared to the risk of the added morbidity of prolonged surgery. Cases excluded at the initial surgery can be either approached in a separate session after a reasonable interval or treated as incidental and asymptomatic meningiomas (Fig. 49-2).

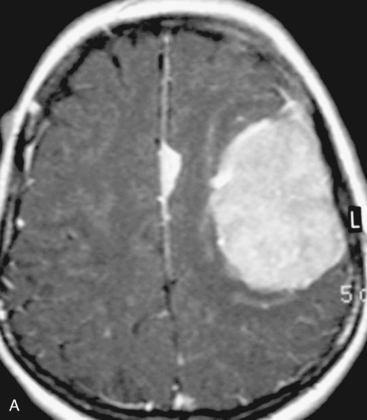

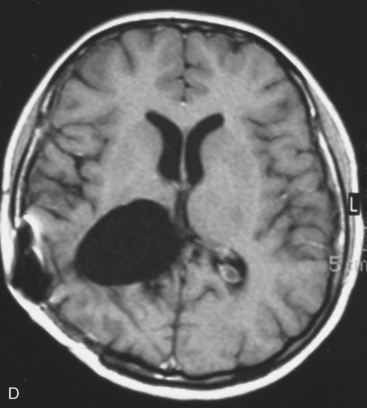

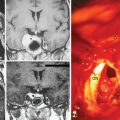

There are several options for multiple meningiomas, either detected incidentally or remaining unresected at previous surgery(s). Observation with sequential imaging can be reserved for small meningiomas at relatively less hazardous locations (Fig. 49-3). In elderly patients or high-risk patients who undergo surgery with residual tumors are increasingly being treated with stereotactic radiotherapy.38 Preliminary reported data appear promising, and this modality can be adapted to unresected multiple meningiomas as well as to residual or recurrent tumor at the primary resection site.

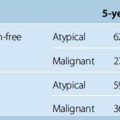

The use of stereotactic radiotherapy with the linear accelerator, Leksell Gamma Knife®, or CyberKnife®, has been used for small recurrent or partially resected tumors as well as primary therapy in surgically inaccessible tumors or in poor surgical candidates.49–51 No study has yet been reported on the role of radiosurgery for multiple meningiomas incidentally detected or intentionally followed as asymptomatic counterparts of resected tumor.52 However, Kano and colleagues published 12 patients with 30 atypical or anaplastic meningiomas. Tumor control rate was 29.4% in the group treated with less than 20 Gy and 63.1% in the group treated with 20 Gy.53 It is reasonable to accept that especially for those with incomplete resections or recurrences, single or fractionated focused radiation should replace conventional radiotherapy in multiple meningiomas. Kollová and co-workers have published the most recent study on radiosurgery for meningiomas. They described their experience in treating 325 benign intracranial meningiomas. Patients were treated with a median marginal dose of 12.6 Gy by using a median of six isocenters. After a median follow-up of 60 months, the 5-year local control was excellent at 97.9%.54 Malik and colleagues treated 309 intracranial meningiomas with either primary (136 tumors) or adjuvant (173 tumors) radiosurgery. The median margin dose was 20 Gy. Although this approach led to a low complication rate of 3%, it gave a 5-year local control of only 87% for benign tumors.55

Deciding between follow-up and prophylactic irradiation for those who are asymptomatic but amenable to resection is highly controversial. However, Condra and colleagues found a 70% rate of tumor progression after subtotal resection without fractionated radiation therapy.52 Kondziolka and colleagues reported 972 patients with intracranial meningiomas treated by Gamma Knife radiosurgery. They separated the patients according to their pathologic grades and reported an overall control rate for all intracranial meningiomas. Tumor control rate for meningiomas (WHO grade I) was 93%, but for patients with WHO grade II to III tumors, control rates were 50% and 17%.56 Future data on the efficacy in disease control as well as side effects of radiosurgery in single meningioma treatment will certainly contribute to management of multiple meningiomas, as well. Although multiple meningiomas would be a perfect target for possible chemotherapeutic treatments such as gene therapy using viral vectors, biological response modifiers, and agents aiming the molecules involved in cell growth, current trials of chemotherapeutic and hormonal agents for disease control in recurrent and aggressive meningiomas do not seem to have a role at this time.

[1] Nasher H.C., Grote W., Lohr E., Gerhardt L. Multiple meningiomas: clinical and computed tomography observations. Neuroradiology. 1981;21:259-263.

[2] Stangl A.P., Wellenreuther R., Lenartz D., et al. Clonality of multiple meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:853-858.

[3] Mufson J.A., Davidoff L. Multiple meningiomas. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1944;1:45-57.

[4] Butti G., Assietti R., Casalone R., Paoletti P. Multiple meningiomas: A clinical, surgical and cytogenetic analysis. Surg Neurol. 1989;31:255-260.

[5] Eljamel M.S., Foy P.M. Multiple meningiomas and their relation to neurofibromatosis. Review of the literature and report of seven cases. Surg Neurol. 1989;32:131-136.

[6] Cushing H., Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas: Their classification, regional behavior, life history, and surgical end results. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas, 1938.

[7] Turgut M., Palaoglu S., Ozcan O.E., et al. Multiple meningiomas of the central nervous system without the stigmata of neurofibromatosis. Clinical and therapeutic study. Neurosurg Rev. 1997;20:117-123.

[8] Gaist G., Piazza G. Meningiomas in two members of the same family (with no evidence of neurofibromatosis. J Neurosurg. 1959;16:110-113.

[9] Ischebec K.V. Proceedings: Multiple meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1975;31:278.

[10] Levin P., Gross S.W., Malis I., et al. Multiple intracranial meningiomas. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1964;119:1085-1090.

[11] List C.F. Multiple meningiomas: Removal of four tumours from the region of foramen magnum and upper cervical region of the cord. Asch Neurol Psychiatry. 1943;50:335-341.

[12] Zhu J.J., Maruyama T., Jacoby L.B., et al. Clonal analysis of a case of multiple meningiomas using multiple molecular genetic approaches: pathology case report. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:409-416.

[13] Bourn D., Carter S.A., Mason S., et al. Germline mutations in the neurofibromatosis type 2 tumor suppressor gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:813-816.

[14] Lekanne Deprez R.H., Bianchi A.B., Groen N.A., et al. Frequent NF2 gene transcript mutations in sporadic meningiomas and vestibular schwannomas. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54:1022-1029.

[15] MacCollin M., Ramesh V., Jacoby L.B., et al. Mutational analysis of patients with neurofibromatosis 2. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:314-320.

[16] Twist E.C., Ruttledge M.H., Rousseau M., et al. The neurofibromatosis type 2 gene is inactivated in schwannomas. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:147-151.

[17] Ruttledge M.H., Sarrazin J., Rangaratnam S., et al. Evidence for the complete inactivation of the NF2 gene in the majority of sporadic meningiomas. Nat Genet. 1994;6:180-184.

[18] Papi L., De Vitis L.R., Vitelli F., et al. Somatic mutations in the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene in sporadic meningiomas. Hum Genet. 1995;95:347-351.

[19] Mérel P., Hoang-Xuan K., Sanson M., et al. Screening for germline mutations in the NF2 gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;12:117-127.

[20] Welling D.B., Guida M., Goll F., et al. Mutational spectrum in the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene in sporadic and familial schwannomas. Hum Genet. 1996;98:189-193.

[21] Jacoby L.B., Jones D., Davis K., et al. Molecular analysis of the NF2 tumor-suppressor gene in schwannomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:1293-1302.

[22] Zucman-Rossi J., Legoix P., Der Sarkissian H., et al. NF2 gene in neurofibromatosis type 2 patients. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:2095-2101.

[23] Ikeda T., Hashimoto S., Fukushige S., et al. Comparative genomic hybridization and mutation analyses of sporadic schwannomas. J Neurooncol. 2005;72:225-230.

[24] Ruttledge M.H., Rouleau G.A. Role of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene in the development of tumors of the nervous system. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:E6.

[25] Ruttledge M.H., Andermann A.A., Phelan C.M., et al. Type of mutation in the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene (NF2) frequently determines severity of disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:331-342.

[26] Bagrodia S., Cerione R.A. Pak to the future. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:350-355.

[27] Kluwe L., Beyer S., Baser M.E., et al. Identification of NF2 germline mutations and comparison with neurofibromatosis phenotypes. Hum Genet. 1996;98:534-538.

[28] Lindblom A., Ruttledge M., Collins V.P., et al. Chromosomal deletions in anaplastic meningiomas suggest multiple regions outside chromosome 22 as important in tumor progression. Int J Cancer. 1994;56:354-357.

[29] Ng H.K., Lau K.M., Tse J.Y.M., et al. Combined molecular genetic studies of 22q and neurofibromatosis type 2 gene in CNS tumors. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:764-773.

[30] Ragel B.T., Jensen R.L. Molecular genetics of meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:E9.

[31] Jarbo C., Mathiesen T., Dumanski J.P. Comprehensive genetic and epigenetic analysis of sporadic meningioma for macro-mutations on 22q and micro-mutations within the NF2 locus. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:16.

[32] Perry A., Gutmann D.H., Reifenberger G. Molecular pathogenesis of meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2004;70:183-202.

[33] Larson J.J., Tew J.M.Jr, Simon M., Menon A.G. Evidence for clonal spread in the development of multiple meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:705-709.

[34] Butti G., Assietti R., Casalone R., Paoletti P. Multiple meningiomas: A clinical, surgical, and cytogenetic analysis. Surg Neurol. 1989;31:255-260.

[35] Ronne M., Poulsgard L. A case of meningioma with multiclonal origin. Anticancer Res. 1990;10:539-542.

[36] Koh Y.C., Yoo H., Whang G.C., et al. Multiple meningiomas of different pathological features: case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2001;8:40-43.

[37] Wood N.W., White R.W., Kernohan J.W. One hundred intracranial meningiomas found incidentally at necropsy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1957;16:337-340.

[38] Rockhill J., Mrugala M., Chamberlain M.C. Intracranial meningiomas: an overview of diagnosis and treatment. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E1.

[39] Andrioli G.C., Rigobello L., Iob I., Casentini L. Multiple meningiomas. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg). 1981;24:67-69.

[40] Gasparetto E.L., Leite C.C., Lucato L.T., et al. Intracranial meningiomas: Magnetic resonance imaging findings in 78 cases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2007;65:610-614.

[41] Biegel J.A., Parmiter A.H., Sutton L.N., et al. Abnormalities of chromosome 22 in pediatric meningiomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;9:81-87.

[42] Perry A., Giannini C., Raghavan R., et al. Aggressive phenotypic and genotypic features in pediatric and NF2-associated meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 53 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:994-1003.

[43] Sadetzki S., Flint-Richter P., Ben-Tal T., et al. Radiation-induced meningioma: a descriptive study of 253 cases. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:1078-1082.

[44] Zattara-Cannoni H., Roll P., Figarella-Branger D., et al. Cytogenetic study of six cases of radiation-induced meningiomas. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001;126:81-84.

[45] Domenicucci M., Santoro A., D’Osvaldo D.H., et al. Multiple intracranial meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:834-835.

[46] Newman S.A. Meningiomas: a quest for the optimum therapy. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:191-194.

[47] Jääskeläinen J. Seemingly complete removal of histologically benign intracranial meningioma: late recurrence rate and factors predicting recurrence in 657 patients. A multivariate analysis. Surg Neurol. 1986;26:261-269.

[48] Mirimanoff R.O., Dosoretz D.E., Linggood R.M., et al. Meningioma: analysis of recurrence and progression following neurosurgical resection. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:18-24.

[49] Kondziolka D., Lunsford D., Coffey R.J., Flickinger J.C. Stereotactic radiosurgery of meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:552-559.

[50] Goldsmith B.J., Wara W.M., Wilson C.B., Larson D.A. Postoperative irradiation for subtotally resected meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:195-201.

[51] Lunsford D.L. Contemporary management of meningiomas: radiation therapy as an adjuvant and radiosurgery as an alternative to surgical removal? J Neurosurg. 1994;80:187-190.

[52] Condra K.S., Buatti J.M., Mendenhall W.M., et al. Benign meningiomas: Primary treatment selection affects survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:427-436.

[53] Kano H., Takahashi J.A., Katsuki T., et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for atypical and anaplastic meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2007;84:41-47.

[54] Kollová A., Liscák R., Novotny J.Jr, et al. Gamma Knife surgery for benign meningioma. J Neurosurg. 2007;10:325-336.

[55] Malik I., Rowe J.G., Walton L., et al. The use of stereotactic radiosurgery in the management of meningiomas. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19:13-20.

[56] Kondziolka D., Mathieu D., Lunsford L.D., et al. Radiosurgery as definitive management of intracranial meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:53-58.

[57] Horrax G. Meningiomas of the brain. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1939;41:140-157.

[58] Vestergaard E. Multiple intracranial meningiomas. Acta Psychiatr Belg. 1944;13:389-411.

[59] Abtahi H. Multiple meningiomas. Acta Neurochir. 1975;31:279.

[60] Ischebeck H., Kuske V. Proceedings: Multiple meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1975;31:278-279.

[61] Lusins J.O., Nakagawa H. Multiple meningiomas evaluated by computed tomography. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:137-141.

[62] Geuna E., Pappada G., Regalia F., et al. Multiple meningiomas, report of 9 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wein). 1983;68:33-43.

[63] Sheehy J.P., Crockard H.A. Multiple meningiomas: a long term review. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:1-5.

[64] Federico F., D’Aprile P., Lorusso A., Belsanti M., Carella A. Multiple meningiomas diagnosed by computed tomography. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1984;5:295-298.

[65] Nakasu S., Hirano A., Shimura T., Llena J.F. Incidental meningiomas in autopsy study. Surg Neurol. 1987;27:319-322.

[66] Locatelli D., Bottoni A., Uggetti C., Gozzoli L. Multiple meningiomas evaluated by computed tomography. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg). 1987;30:8-10.