Chapter 188 Moraxella catarrhalis

Clinical Manifestations

Acute Otitis Media

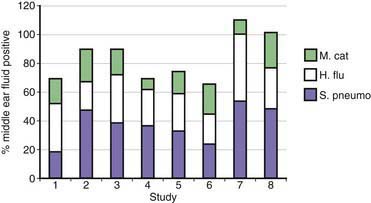

Approximately 80% of children have one or more episodes of otitis media by age 3 yr. Otitis media is the most common reason for which children receive antibiotics. On the basis of culture of middle ear fluid obtained by tympanocentesis, the predominant causes of acute otitis media are S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis (Fig. 188-1). Overall, M. catarrhalis causes 15-20% of cases of otitis media. The distribution of the causative agents of otitis media is changing as a result of widespread administration of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, with a relative increase in H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis.

Treatment

A proportion of cases of M. catarrhalis otitis media resolve spontaneously. Treatment of otitis media is empirical, and clinicians are advised to follow guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics (Chapter 632).

Deshpande LM, Sader HS, Fritsche TR, Jones RN. Contemporary prevalence of BRO beta-lactamases in Moraxella catarrhalis: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (North America, 1997 to 2004). J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3775-3777.

Hall-Stoodley L, Hu FZ, Gieseke A, et al. Direct detection of bacterial biofilms on the middle-ear mucosa of children with chronic otitis media. JAMA. 2006;296:202-211.

Heiniger N, Spaniol V, Troller R, et al. A reservoir of Moraxella catarrhalis in human pharyngeal lymphoid tissue. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1080-1087.

Murphy TF, Paramswaran GI. Moraxella catarrhalis, a human respiratory tract pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:124-131.

Revai K, McCormick DP, Patel J, et al. Effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on nasopharyngeal bacterial colonization during acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1823-1829.

Ruckdeschel EA, Kirkham C, Lesse AJ, et al. Mining the Moraxella catarrhalis genome: identification of potential vaccine antigens expressed during human infection. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1599-1607.

Slevogt H, Seybold J, Tiwari KN, et al. Moraxella catarrhalis is internalized in respiratory epithelial cells by a trigger-like mechanism and initiates a TLR2- and partly NOD1-dependent inflammatory immune response. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:694-707.

Tan TT, Riesbeck K. Current progress of adhesins as vaccine candidates for Moraxella catarrhalis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007;6:949-956.

Verhaegh SJ, Streefland A, Dewnarain JK, et al. Age-related genotypic and phenotypic differences in Moraxella catarrhalis isolates from children and adults presenting with respiratory disease in 2001–2002. Microbiology. 2008;154:1178-1184.

Wirth T, Morelli G, Kusecek B, et al. The rise and spread of a new pathogen: seroresistant Moraxella catarrhalis. Genome Res. 2007;17:1647-1656.