Chapter 31

Mitral Stenosis, Mitral Regurgitation, and Mitral Valve Prolapse

1. What is the usual cause of mitral stenosis (MS)?

2. What is the pathophysiology of MS?

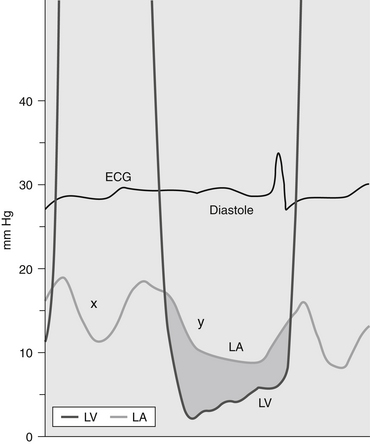

MS inhibits the normal free flow of blood from left atrium (LA) to left ventricle (LV) in diastole. Normally, diastolic LA and LV pressures equalize shortly after mitral valve opening. In MS, the stenotic valve impedes LA emptying, inducing a diastolic gradient between LA and LV (Fig. 31-1). Elevated LA pressure is referred to the lungs, where it causes pulmonary congestion. Simultaneously, impaired LA emptying reduces LV filling, limiting cardiac output. Thus, the combination of increased LA pressure and decreased cardiac output produce the syndrome of heart failure. Because increased LA pressure increases pulmonary pressure, the right ventricle (RV) becomes pressure overloaded, eventually leading to RV failure.

Figure 31-1 Pressure gradient in a patient with mitral stenosis. The pressure in the left atrium (LA) exceeds the pressure in the left ventricle (LV) during diastole, producing a diastolic pressure gradient (shaded area). (Modified from Bashore TM: Invasive cardiology: principles and techniques, Philadelphia, 1990, BC Decker, p. 264.) ECG, Electrocardiogram.

3. What are the typical symptoms of MS?

4. What are the signs of MS at physical examination?

5. How is the diagnosis of MS made?

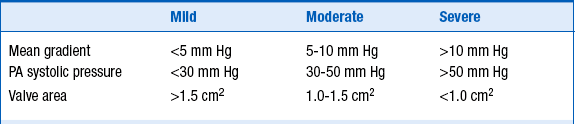

Today, however, the echocardiogram is key to the diagnosis because it images the mitral valve so well. The valve is thickened and there is impaired opening of the mitral leaflets (Fig. 31-2). The LA is almost always enlarged. Valve area can be determined from direct visualization and planimetry of the mitral orifice, from Doppler assessment of the transvalvular gradient, and from measuring the delay in LA emptying. Pulmonary pressure, LV function, and RV function are also evaluated. In general, the main criteria for severe MS follow below. The severity of MS is estimated using the criteria given in Table 31-1.

TABLE 31-1

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC CRITERIA FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF THE SEVERITY OF MITRAL STENOSIS

Modified from Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al: ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. J Amer Coll Cardiol 48:e1-e148, 2006.

Figure 31-2 Two-dimensional echocardiogram of the parasternal long-axis view during diastole of a patient with mitral stenosis. The mitral valve leaflets are thickened and have the typical hockey-stick appearance (arrow). Note also that the left atrium (LA) is enlarged. LV, Left ventricle; RV, right ventricle. (Modified from Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.)

6. Is there effective medical management for MS?

7. What is the definitive management for severe MS?

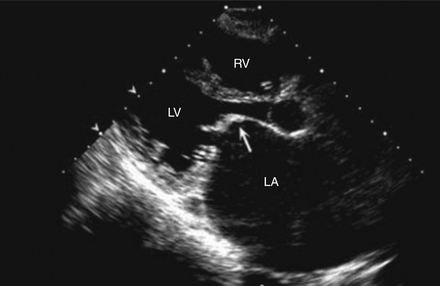

If symptoms cannot be controlled easily medically or if asymptomatic pulmonary hypertension develops, this mechanical lesion must be treated by mechanical relief of the stenosis, because either condition worsens MS prognosis. In most cases, mitral balloon valvotomy is the preferred therapy. In this procedure, a balloon is passed percutaneously from the femoral vein across the atrial septum (by needle puncture) through the mitral valve, where it is inflated (Fig. 31-3). Balloon inflation ruptures the adhesions at the commissures caused by the rheumatic process, allowing as much as doubling of the mitral valve area and normalizing cardiac output, LA pressure, and PA pressure, in turn, relieving symptoms.

Figure 31-3 Percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy (BMV) for mitral stenosis using the Inoue technique. A, The catheter is advanced into the left atrium via the transseptal technique and guided antegrade across the mitral orifice. As the balloon is inflated, its distal portion expands first and is pulled back so that it fits snugly against the orifice. With further inflation, the proximal portion of the balloon expands to center the balloon within the stenotic orifice (left, arrowheads). Further inflation expands the central waist portion of the balloon (right), resulting in commissural splitting and enlargement of the orifice. B, Successful BMV results in significant increase in mitral valve area, as reflected by reduction in the diastolic pressure gradient between left ventricle (LV) and pulmonary capillary wedge (PCW) pressure, as indicated by the shaded area. (From Delabays A, Goy JJ: Images in clinical medicine: percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty, N Engl J Med 345:e4, 2001.)

Criteria have been established to determine whether balloon valvotomy should be performed or the patient referred for surgery. These four criteria are valve mobility, subvalvular thickening, leaflet thickening, and degree of valvular calcification. In addition to these characteristics, the degree of mitral regurgitation (MR) is assessed, because balloon valvotomy can worsen the degree of mitral regurgitation. Balloon valvotomy is ineffective when mitral annular calcification is the cause of MS.

Class I indications for percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy include the following:

Symptomatic (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class II to IV) patients with moderate to severe MS with favorable valve characteristics, in the absence of LA thrombus or moderate to severe MR (class I; level of evidence A)

Symptomatic (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class II to IV) patients with moderate to severe MS with favorable valve characteristics, in the absence of LA thrombus or moderate to severe MR (class I; level of evidence A)

Asymptomatic patients with moderate to severe MS and pulmonary hypertension (PA systolic pressure greater than 50 mm Hg at rest or more than 60 mm Hg with exercise) and valve morphology favorable for balloon valvotomy, in the absence of LA thrombus or moderate to severe MR (class I; level of evidence C)

Asymptomatic patients with moderate to severe MS and pulmonary hypertension (PA systolic pressure greater than 50 mm Hg at rest or more than 60 mm Hg with exercise) and valve morphology favorable for balloon valvotomy, in the absence of LA thrombus or moderate to severe MR (class I; level of evidence C)

9. How does primary MR affect the LV?

10. What are the other effects of primary MR on the heart and lungs?

11. What are the clues to MR on physical examination?

12. How is the diagnosis of MR confirmed?

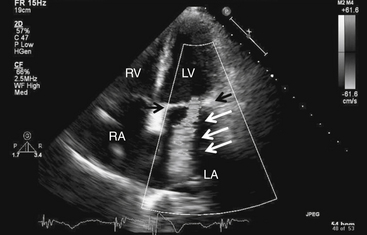

Although both the chest radiograph and the electrocardiogram (ECG) may indicate LV enlargement, as with other valvular heart diseases, echocardiography is the diagnostic modality of choice (Fig. 31-4). It demonstrates LA and LV size and volume, allows assessment of LV function and PA pressure, and can reliably quantify the amount of MR present.

Figure 31-4 Mitral regurgitation. Apical four-chamber view with color Doppler revealing severe mitral regurgitation (white arrows). Black arrows point to the mitral valve. Note that in actuality, the regurgitant jet is displayed in color, corresponding to the flow of blood. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

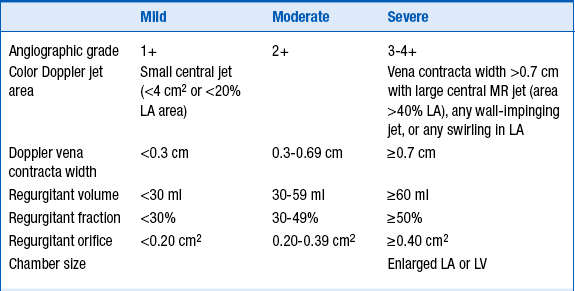

Severity of MR is established using the criteria in Table 31-2. Magnetic resonance imaging may be used to establish or confirm the severity of MR and its attendant volume overload.

TABLE 31-2

ANGIOGRAPHIC AND ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC CRITERIA FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF THE SEVERITY OF MITRAL REGURGITATION

LA, Left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MR, mitral regurgitation.

Modified from Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al: ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. J Amer Coll Cardiol 48:e1-e148, 2006.

13. Are there effective medical therapies for chronic primary MR?

14. What is the definitive therapy for primary MR, and when should it be employed?

Because the onset of symptoms worsens prognosis for patients with MR, mitral valve repair should be performed at that time. However, some patients fail to develop symptoms even though LV dysfunction has ensued. To guard against permanent LV dysfunction, mitral surgery should be performed before ejection fraction falls to 60% or less, or before the LV can no longer contract to an end-systolic dimension of 40 mm. The onset of atrial fibrillation or pulmonary hypertension is also an indication for surgery. It should be noted that not all mitral valves can be repaired. In such cases, mitral valve replacement is performed.

Class 1 indications for mitral valve repair or replacement include the following:

Development or presence of NYHA class II to IV symptoms in patients with chronic severe MR in the absence of severe LV dysfunction (ejection fraction less than 30% or end-systolic dimension greater than 55 mm)

Development or presence of NYHA class II to IV symptoms in patients with chronic severe MR in the absence of severe LV dysfunction (ejection fraction less than 30% or end-systolic dimension greater than 55 mm)

Asymptomatic patients with chronic severe MR and mild to moderate LV dysfunction (ejection fraction of 30%-60% or end-systolic dimension 40 mm or more)

Asymptomatic patients with chronic severe MR and mild to moderate LV dysfunction (ejection fraction of 30%-60% or end-systolic dimension 40 mm or more)

15. How is secondary MR managed?

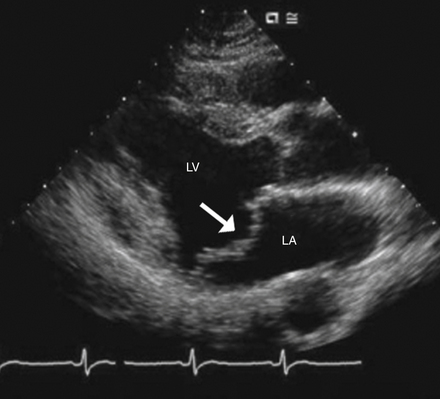

16. What is mitral valve prolapse?

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is the condition in which there is systolic billowing of one or both mitral leaflets into the LA (Fig. 31-5), with or without resulting MR. It is usually diagnosed by echocardiography, according to established criteria (valve prolapse of 2 mm or more beyond the mitral annulus, as seen in the parasternal long-axis view). Its prevalence is 1% to 2.5%.

Figure 31-5 Mitral valve prolapse. The mitral leaflets prolapse across the plain of the mitral valve, into the left atrium (arrow). LA, Left atrium; LV, left ventricle. (Modified from Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.)

17. What is the classic auscultatory finding in MVP?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Bonow, R.O., Carabello, B.A., Chatterjee, K., et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:e1–e148.

2. Carabello, B.A. The pathophysiology of mitral regurgitation. J Heart Valve Dis. 2000;9:600–608.

3. Carabello, B.A. Modern management of mitral stenosis. Circulation. 2005;112:432–437.

4. Carabello, B.A. The current therapy for mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:319–326.

5. Gaasch W.H.: Overview of the Management of Chronic Mitral Regurgitation. In Basow, DS, editor: UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013, UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-management-of-chronic-mitral-regurgitation. Accessed March 26, 2013.

6. Feldman, T., Foster, E., Glower, D.D., et al. Percutaneous repair or surgery for mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1395–1406.

7. Hanson, I. Mitral regurgitation. Available at http://www.emedicine.com. Accessed March 26, 2013

8. CM Otto, Pathophysiology and Clinical Features of Mitral Stenosis. In Basow, DS, editor: UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013, UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathophysiology-clinical-features-and-evaluation-of-mitral-stenosis. Accessed March 26, 2013.

9. Dima, C. Mitral stenosis. Available at http://www.emedicine.com. Accessed March 26, 2013

10. Vahanian, A., Baumgartner, H., Bax, J., et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease: the Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:230–268.