chapter 14

Miscellaneous Neurological Disorders

The principal aim of this textbook has been to introduce simple concepts to help the ‘student of neurology’ understand the diagnostic process and to discuss the more common neurological problems encountered in everyday clinical practice. There are a number of conditions that are not common in everyday clinical practice, and yet no neurology textbook would be complete without at least some discussion of those entities. This chapter will discuss:

• assessment of patients with a depressed conscious state

• assessment of the confused or demented patient

• disorders of muscle and the neuromuscular junction

ASSESSMENT OF PATIENTS WITH A DEPRESSED CONSCIOUS STATE

The definitive text on this subject has been written by Fred Plum and Jeremy Posner in a superb text, entitled The Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma [1], that is required reading for every neurologist in training.

Essentially there are three patterns of a depressed conscious state:

1. Diffuse – consciousness is depressed in the absence of neurological signs. The main causes include:

• drugs (alcohol, opiates and sedatives)

• hypothermia (may cause coma if the temperature is less than 31°C), meningitis, encephalitis

• subarachnoid haemorrhage, acute hydrocephalus

• severe hypotension from any cause

• metabolic disturbances such as hypoxaemia, hepatic coma, hyponatraemia or hypernatraemia, hypercapnia

2. Cerebral hemisphere problems – the conscious state is depressed in the setting of a hemiparesis or hemiplegia. Conditions that produce a mass effect cause downward herniation of the brain through the tentorium and secondary compression of the brainstem. Such conditions include:

3. Diseases in the brainstem – the conscious state is depressed and there are abnormalities in the brainstem reflexes. These include:

• The airway is not obstructed.

• The patient is breathing adequately; if not, intubate them.

• The circulation, pulse and blood pressure and, if the patient is hypotensive, treat with appropriate fluids and if necessary pharmacological agents.

1. Look at the pupils. If they are pinpoint, administer naloxone. (Pontine haemorrhage and narcotic or barbiturate overdose result in pinpoint pupils.)

Neurological examination of patients in a depressed conscious state

Often patients are found unconscious and a detailed history is not possible.

• As much information as possible should be obtained from an eyewitness, if there is one, or from the person who found the patient.

• Attempt to establish when the patient was last seen well, as this helps to narrow down the time the patient may have been unconscious for.

• Have people check for empty bottles or a suicide note near where the patient was found, which indicate the possibility of a drug overdose.

• Question ambulance officers rather than rely on the ambulance report.

• Telephone relatives, neighbours or anybody who might be able to provide clues to the diagnosis.

• Ask about evidence to suggest trauma, e.g. overturned furniture, blood on the floor, syringes to suggest possible drug overdose from medications (e.g. insulin or hypoglycaemics) the patient takes.

• See if there is anything in the past medical history that may provide a clue.

The next step is to attempt to arouse the patient with verbal stimuli and, if it fails, painful stimuli (Figure 14.1). One of the most useful techniques is to pinch the skin on the medial aspect of the elbows and knees between your fingernails. A normal response is abduction of the limbs away from the painful stimulus; an abnormal response is adduction of the limbs towards the painful stimulus or extension of the limbs. Before testing the response to painful stimuli in front of the family, explain to them that it is the way to test when someone is unconscious. The family should also be warned that this technique may leave bruises.

The brainstem reflexes are then examined. The region tested is shown in brackets.

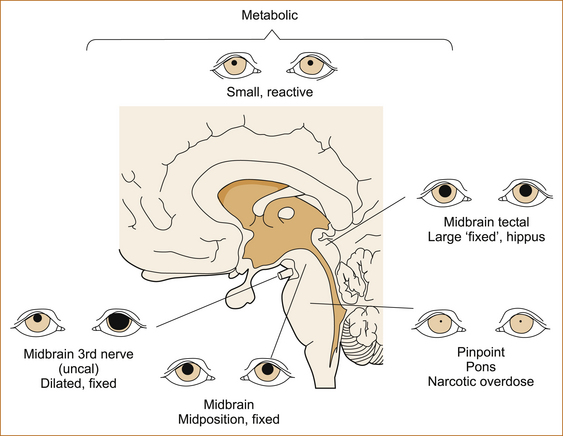

• The pupil responses – the afferent pathway is the 2nd nerve; the efferent pathway is the parasympathetic pathway on the surface of the 3rd nerve (midbrain and 3rd nerve)

• Doll’s eye reflexes – spontaneous and head movement-evoked eye movements (vertical eye movements = midbrain, horizontal eye movements = pons) (Figure 14.1)

• The corneal and nasal tickle reflexes – the afferent pathway is the 5th cranial nerve; the efferent pathway is the 7th nerve (pons) (Figure 14.1)

• The gag reflex – the afferent pathway is the 9th cranial nerve; the efferent pathway is the 10th cranial nerve (medulla)

Response to pain

Decorticate and decerebrate rigidity are two terms used to describe certain postures that may occur in the comatose patient and were formerly thought to provide localising value, although this is now in question. Decorticate rigidity refers to flexion of the elbows and wrists and supination of the arms and was said to indicate bilateral damage above (rostral) to the midbrain; decerebrate rigidity consists of extension of the elbows and wrists with pronation of the forearms indicating damage to the motor pathways in the midbrain or lower part (caudal) of the diencephalon (thalamus and hypothalamus). Similarly, the pattern of respiration is not of great localising value. For example, the cyclic breathing with periods of apnoea referred to as Cheyne–Stokes respiration can occur with bilateral hemisphere damage or metabolic suppression of the conscious state.

The pupil responses

The response of the pupils to a bright light is one of the most important aspects of the examination (see Figure 14.2). It may be necessary to use a magnifying glass to see slight reactions. The size of the pupil and the reaction to light are used to exclude or localise pathology in or affecting the midbrain and pons of the brainstem.

• Bilateral normal size (2.5–5mm) and reactive pupils:

• Unilateral dilated (> 6 mm) and non-reactive pupil + contralateral weakness:

• Compression of the ipsilateral 3rd cranial nerve with herniation due a mass lesion (tumour, haemorrhage, oedema related to a cerebral infarct) in the cerebral hemisphere

• Bilateral dilated and non-reactive pupils:

The eye movements

In normal patients the eyes may be divergent in sleep.

• Spontaneous movements of the eyes, referred to as ‘roving eyes’, exclude damage to the midbrain and pons.

• If the eyes are deviated to one side, this is either due to an ipsilateral hemisphere lesion, where the eyes look to the side of the lesion and away from the side of the paralysis, or alternatively may indicate pontine pathology, where the eyes look away from the side of the lesion and towards the side of the paralysis or hemiparesis. One exception to this rule is that with irritating hemisphere lesions the eyes may be deviated away from the side of the lesion and towards the side of the paralysis.

• Ocular bobbing indicates bilateral pontine damage, most often seen with basilar artery thrombosis. It consists of the absence of horizontal eye movements and a characteristic brisk downward movement of both eyes and then a slow upward movement to return to the normal position.

In the absence of these spontaneous ocular signs, the brainstem can be tested using the technique referred to as the oculocephalic reflex or doll’s eye test (see Figure 14.1C).

• The head is moved rapidly horizontally and then vertically while the movement of the eyes in the opposite direction to the movement of the head is observed.

• When the head is turned to the right, the eyes deviate fully left and vice versa.

• If the eye movement is full, i.e. the eyes move in the orbits to their full extent so that no sclera can be seen, this indicates that the brainstem is intact and therefore not the site of the pathology causing the impaired consciousness.

• If the eyes fail to move, this suggests damage to the ipsilateral brain stem nuclei.

• In patients with severe depression of the conscious state due to drug overdose, the oculocephalic reflexes may be abnormal and not indicate any structural damage to the brainstem. In this latter setting the pupils would usually be of normal size and react to light, something that would not occur in destructive brainstem lesions.

ASSESSMENT OF THE CONFUSED OR DEMENTED PATIENT

Confusion, delirium and dementia

CONFUSION AND DELIRIUM

Delirium is an acute and relatively sudden (developing over hours to days) decline in attention–focus, perception and cognition. The patient appears out of touch with their surroundings and is spontaneously producing evidence of this confusion, such as a lack of clear and orderly thought and behaviour, disorientation with muttering, restlessness, rambling and shouting (often offensively and continuously) with evidence of delusion and hallucinations. It is not synonymous with drowsiness and may occur without it. Other features of delirium can include: depression, memory problems, difficulty writing or finding words and disturbances of the sleep–wake cycle.

The International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition [2], defines delirium as:

• impairment of consciousness and attention;

• global disturbance of cognition (including illusions, hallucinations, delusions and disorientation);

neologisms (see Chapter 5, ‘The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum’) or non-dominant parietal lobe lesions with patients ‘lost in space’. A quick screening examination (if the patient can cooperate) with double simultaneous stimuli in the visual fields and asking the patient to hold their arms out could detect the visual inattention and parietal drift that would alert one to focal rather than diffuse brain pathology.

DEMENTIA

Potentially treatable causes of dementia include:

• vitamin B1 or vitamin B12 deficiency

• normal pressure hydrocephalus

• chronic infections or inflammation such as syphilis, meningitis related to tuberculosis, cryptococcus, sarcoidosis and the extremely rare entity of Whipple’s disease.

It is anticipated that future discoveries will lead to even more cases of treatable dementia.

Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s disease is the commonest cause of dementia and, at the time of writing this textbook, the definitive diagnosis still requires histopathological demonstration of sufficient numbers of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles and is therefore not usually possible in life. The risk of Alzheimer’s increases with advancing age and 20–40% of patients over the age of 85 will have Alzheimer’s disease. A positive family history is not uncommon. Patients with Down syndrome (trisomy 21) have an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease after the age of 40.

Most patients with Alzheimer’s disease will present with the insidious onset over many years of memory impairment, particularly short-term memory. As cognitive function declines the patient develops increasing difficulties with daily activities and it is this difficulty that differentiates mild cognitive impairment from true dementia. A reversal of the sleep cycle with patients sleeping during the day and wandering at night is not uncommon. Some patients with Alzheimer’s disease are unaware of their cognitive impairment and it is concerned relatives that urge them to seek medical attention. Patients may cope well in their home environment, but often the dementia is unmasked when they are admitted to hospital or when they travel and are placed in an unfamiliar environment. As the disease relentlessly progresses, patients become lost when they go for walks or when they are driving, and they have difficulty with finances, housekeeping, shopping and following instructions. Leaving the stove on is a common complaint. Walking becomes difficult and patients may develop a characteristic disorder of gait referred to as the apraxic gait (see Chapter 13, ‘Abnormal movements and difficulty walking due to central nervous system problems’). Language function deteriorates with difficulty naming objects, comprehension and then subsequently the development of aphasia. In advanced Alzheimer’s patients are no longer able to care for themselves in terms of dressing, bathing and feeding and eventually lose control of bladder and bowels.

Depression can present with many of the clinical features of dementia that resolve with treatment of the depression and this is referred to as ‘pseudodementia’. It is the intellectual impairment in patients with a primary psychiatric disorder, in which the features of intellectual abnormality resemble, at least in part, those of a neuropathologically induced cognitive deficit. These patients often complain of memory disturbance and yet are often able to recant the history of their ‘cognitive decline’ without much difficulty. The correct diagnosis may only reveal itself when the patient improves with treatment for depression. Reynolds et al [6] in a small study found that significantly greater pretreatment early morning awakening, higher ratings of psychological anxiety and more severe impairment of libido were features of pseudodementia whereas patients with dementia showed significantly more disorientation to time, greater difficulty finding their way about familiar streets or indoors and more impairment with dressing.

In very rare instances dementia may begin with focal neurological deficits [7–10] and a number of syndromes have been identified, such as posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), corticobasal syndrome (CBS), behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA) (or a mixed aphasia) and semantic dementia (SD). In some instances these patients will have the pathological features of Alzheimer’s disease. These focal syndromes may remain pure for many years before the subsequent appearance of other signs of dementia. The underlying neuropathology does not uniquely associate the clinical syndromes with distinctive patterns of pathological markers. A detailed discussion of these entities is beyond the scope of this textbook [7, 9, 10].

Rapidly progressive dementia (RPD): Rapidly progressive dementias can develop subacutely over months, weeks or even days and be quickly fatal. Prion disease (Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease) is the commonest cause, but some cases of frontotemporal dementia (FTD), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and progressive supranuclear palsy may sometimes present in a fulminant form with death occurring in less than 3 years [11].

Forgetfulness or early dementia: Forgetfulness or absent-mindedness is a feature of the ageing process. Most patients over the age of 70 complain of problems with memory and many patients seek medical attention concerned about the possibility of dementia. It can be very difficult in the early stages to differentiate between these two processes [12]. Episodic memory loss precedes widespread cognitive decline in early AD [13].

DISORDERS OF MUSCLE AND THE NEUROMUSCULAR JUNCTION

Diseases of muscle and conditions affecting the neuromuscular junction are very rare. For example, the prevalence of inflammatory muscle disease is estimated to be 1 in 100,000 and of myasthenia gravis is 8 in 100,000. A complete discussion of all disorders of muscle is well beyond the scope of this text and interested readers will find many excellent reviews, textbooks and websites [15–18].

• Muscle pain or myalgia, apart from (therapeutic) drug-induced muscle pain, is rare in muscle diseases and more often relates to rheumatological, psychiatric or orthopaedic disorders, although it may occur in patients with congenital or endocrine myopathies and myositis. It is important to question about the use of prescription and non-prescription medications when a patient presents with muscle pain.

For a recent review on drug-induced myopathies, refer to Klopstock [19].

• Fatigue is also a very non-specific symptom. Patients with depression, for example, often complain of fatigue; however, fatigue in the form of exercise intolerance may point to involvement of the neuromuscular junction with conditions such as myasthenia gravis and the Lambert–Eaton syndrome. Fatigue is also a prominent symptom in patients with motor neuron disease.

• Muscle cramps are seen with hyponatraemia, renal failure, hypothyroidism and many other conditions that affect peripheral nerves.

• Myotonia is the inability to relax a muscle after forced voluntary contraction, for example gripping an object with the hands. It is seen in some of the hereditary disorders of muscle such as myotonic dystrophy and Thompson’s disease as well as acquired disorders such as neuromyotonia (Isaac’s syndrome).

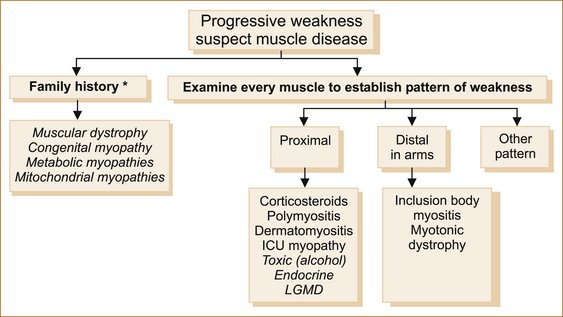

There are many approaches to patients with suspected muscle disease; one is shown in Figure 14.3.

FIGURE 14.3 An approach to patients with suspected muscle disease

Note: The uncommon diseases are in italics.

∗A ‘negative’ family history does not exclude inherited disorders of muscle. ‘Other’ pattern refers to patterns of weakness other than proximal or distal, for example fascioscapulohumeral.

ICU = intensive care unit; LGMD = limb-girdle muscular dystrophy

1. The initial step is to establish if there is a family history, as many diseases of muscle, such as the muscular dystrophies and the congenital, metabolic and mitochondrial myopathies, are inherited disorders of muscle and there will be another member of the family affected. It is important to remember that a negative family history does not exclude hereditary disorders of muscle. Some patients are so mildly affected that they are not aware of the problem or have not sought medical attention. This is not uncommon in patients with muscular dystrophy.

2. The age of onset can provide another clue, e.g. congenital myopathies may be present at birth, the muscular dystrophies often develop in the first few years of life and inclusion body myositis is predominantly seen in elderly patients.

3. Consider the rapidity of onset of the weakness. Many disorders of muscle, particularly the inherited disorders of muscle, develop gradually over many, many years; most of the acquired disorders of muscle, for example the inflammatory myopathies, on the other hand progress rapidly over months. Patients with congenital myopathies may not progress at all. Fluctuating weakness suggests disorders of the neuromuscular junction, such as myasthenia gravis and the Lambert–Eaton syndrome. Recurrent attacks of weakness are a feature of the periodic paralyses and certain glycolytic pathway disorders.

4. Define the pattern of weakness. Many conditions of muscle have been labelled according to the pattern of weakness, for example limb-girdle muscular dystrophy or fascioscapulohumeral dystrophy. This may be less important in the future. As the underlying genetic bases for the muscle diseases are defined, it is increasingly apparent that there is great variability in the phenotypic expression (the pattern of weakness), reflecting the severity of the underlying the genetic defect. For example, with mutations in the dysferlin gene, patients can present with the pattern of a limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, a distal anterior compartment myopathy or the classic Miyoshi myopathy with multifocal weakness and wasting [20]. The term ‘dysferlin deficient muscular dystrophy’ has replaced the term ‘Miyoshi myopathy’. The classification of the limb-girdle dystrophies continues to be revised on the basis of the elucidation of the underlying protein and genetic abnormalities [21]. In everyday clinical practice, other than a proximal muscle weakness, the ‘proximal myopathy’ that is probably the most common pattern and distal weakness in the forearms, most of the other disorders of muscle are extremely rare.

5. Look for associated phenomena that may help differentiate one condition from another.

• Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy

• Hepatomegaly: metabolic or alcoholic myopathies

• Central nervous system involvement may occur in patients with mitochondrial myopathies [15]

• Measure the creatinine kinase (CK). CK is elevated in most but not all disorders of muscle and in itself is not a particularly useful test to differentiate one disorder of muscle from another; however, a markedly elevated CK is seen with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and the dysferlinopathies.

• Thyroid function tests and electrolytes should be routine and parathyroid hormone and human immuno-deficiency virus (HIV) in selected cases.

• Inflammatory myopathies can be associated with connective tissue diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis; thus an antinuclear factor (ANF), double-stranded DNA and rheumatoid factor tests should be performed in these patients.

7. The urine should be examined for myoglobinuria in patients with exercise-induced muscle pain.

8. A forearm ischaemic lactate test is performed in patients suspected of having a metabolic myopathy; a less than threefold increase in the lactate is abnormal.

9. Perform nerve conduction studies and in particular electromyography. Nerve conduction studies are normal in patients with muscle disease (exceptions include mitochondrial disorders, myotonic dystrophy and inclusion body myositis). Electromyography (EMG) can confirm the presence of a myopathy with the demonstration of brief small amplitude polyphasic potentials (BSAPPs) and a full recruitment pattern with minimal effort; exclude other conditions such as motor neuron disease, peripheral neuropathy and disorders of the neuromuscular junction. Occasionally the nerve conduction studies and EMG can be completely normal in patients with muscle disease. The presence of fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves with the myopathic changes described above indicate a likely inflammatory myositis such as polymyositis, dermatomyositis or inclusion body myositis. The sound of a motorbike or dive bomber on EMG is seen with myotonia in myotonic and congenital muscular dystrophies.

10. Biopsy an affected muscle. This can be performed using an open biopsy procedure or a needle biopsy; the latter is less invasive and multiple samples can be taken but the size of the individual samples is small. It is important to remember that pathological changes may be focal and thus a normal biopsy does not exclude muscle disease. It is more rewarding to biopsy an affected muscle, but not one that is so severely affected that the likely pathology will be non-diagnostic end-stage muscle. It is also important not to biopsy a muscle at the site of EMG as the EMG needle will cause abnormal pathology. Increasingly sophisticated pathological methods, such as immunohistochemical staining with a panel of antibodies, quantitative analysis of proteins by western blotting and DNA analysis, are now a routine part of the pathological examination of muscle and help to determine the cause of muscle weakness in most patients.

Note: The unravelling of the genome is in some instances already replacing muscle biopsy with non-invasive molecular genetics studies in the hereditary muscle diseases [15, 22]. DNA analysis is becoming the gold standard for the diagnosis.

Muscle diseases causing distal weakness in the arms

Although there are many causes of distal weakness in the arms [16], myotonic dystrophy and inclusion body myositis are the two commonest conditions that result in distal weakness in the forearms. Some of the limb-girdle muscular dystrophies may involve distal as well as proximal weakness [21].

The inflammatory myopathies

POLYMYOSITIS AND DERMATOMYOSITIS

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis should be suspected in patients who develop weakness over a period of months. The weakness is symmetrical and affects proximal muscles in the limbs with weakness of shoulder abduction and hip flexion; associated neck flexion weakness is a clue to the diagnosis. Rarely, the bulbar (muscles innervated by the 9th, 10th and 12th cranial nerves) and respiratory muscles may be affected. Patients with dermatomyositis have characteristic skin changes such as the heliotrope rash resulting in violaceous discoloration of the eyelids, scaly erythema over the joints on the dorsal aspect of the hands, macular erythema on the posterior neck and shoulders or on the anterior neck and chest or a violaceous erythema associated with increased pigment and telangiectasia on the anterior neck, chest, posterior shoulders, back and buttocks.

INCLUSION BODY MYOSITIS

Inclusion body myositis (IBM) is a sporadic condition seen predominantly in patients over the age of 50. IBM has a pathognomonic pattern of weakness affecting the quadriceps muscle with severe weakness of knee extension resulting in frequent falls as the knees give way in addition to the distal weakness in the forearms and hands with weakness of flexion of the fingers. Hip flexion weakness is much less severe than the knee extension weakness. Dysphagia is common but involvement of the respiratory muscles is rare [31]. The muscle biopsy demonstrates inflammatory cells and vacuoles in muscle fibres.

Drug-induced myopathies

Side effects from the use of drugs are rare and occur in less than 0.5% of patients. They include muscle pain that can be mild and not require cessation of the drug or severe and associated with fatigue and elevation of the CK to more than 10 times the upper limit of normal (ULN). Other complications include a proximal muscle weakness or rhabdomyolysis which at times is fatal. Myopathy is more common in patients on multiple therapeutic agents and may relate to drug–drug interactions. Although the CK is usually elevated, a normal value does not exclude a drug-induced myopathy [33]. The myopathy may take months or even years to develop, and symptoms may persist for some time after cessation of the drug [34].

Statins, fibrates, antidepressants, antipsychotic drugs, benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers, corticosteroids, alcohol, cocaine, amphetamines, colchicines and heroin are some of the drugs that can produce myopathy including rhabdomyolysis.

Weakness and fatigue

MYASTHENIA GRAVIS AND LAMBERT–EATON SYNDROME

The two currently recognised disorders that affect the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) are myasthenia gravis [35] and the Lambert–Eaton syndrome, also referred to as the Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome [36]. Patients with myasthenia gravis observe that their weakness is exacerbated by exercise, whereas patients with the Lambert–Eaton syndrome complain of weakness and fatigue unrelated to exercise. Patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (motor neuron disease) may also complain of a significant exacerbation of weakness with exercise, but the severe fixed weakness, wasting and fasciculations seen in motor neuron disease are not seen in the disorders of the NMJ [37].

Both are immune-mediated disorders.1 Lambert–Eaton syndrome is often associated with malignancy, particularly small cell carcinoma of the lung [40], but may also occur as an autoimmune disease in the absence of malignancy [41]. Myasthenia gravis may be associated with a tumour of the thymus [42], either benign or malignant; this is more common in elderly patients and younger patients tend to have thymic hyperplasia or aplasia of the thymus.

Myasthenia gravis is classified as either ocular if it just affects the ocular muscles (including the eyelids) or generalised if it affects the facial, bulbar and limb muscles. The characteristic feature is the exacerbation of the weakness with exercise or prolonged use of the muscles. Variable ptosis (drooping of the eyelid) and variable diplopia with a mixture of horizontal and vertical diplopia at different times occur with ocular myasthenia gravis, although the occasional patient does not observe variable diplopia leading to the incorrect diagnosis of a 3rd, 4th or 6th nerve palsy or an internuclear ophthalmoplegia (a lesion of the median longitudinal fasciculus in the brainstem).2 The ocular muscles may also be affected in patients with generalised myasthenia gravis. Patients with generalised myasthenia may complain of difficulty holding their head up while watching television due to weakness of the extensor muscles of the neck, increasing dysarthria the more they speak; problems with chewing or swallowing food, again worse with prolonged chewing; increasing weakness leading to difficulty holding the arms up above the head when washing the hair or putting clothes on the clothes line. Patients have to rest momentarily before they can continue this activity. During the examination increasing degrees of ptosis and diplopia can be elicited by asking the patient to look up for a prolonged period of time; fatiguable weakness in the limbs can be elicited with repetitive exercise. A quick test in patients with suspected ocular myasthenia is to place ice on the eyelid and see the temporary resolution of the ptosis [43]. Changes in the degree of diplopia with the ice test should be interpreted with caution [44].

The reflexes are normal and are not influenced by exercise. There are a number of diagnostic tests for myasthenia gravis with variable sensitivity but high specificity (see Table 14.1).

TABLE 14.1

Sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic tests in myasthenia gravis

| Test | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) |

| Tensilon test [45] | 92 (83–100%) | 97 (91–100) |

| Ice test [43] | 95 (87–100) | 97 (90–100) |

| ACHR antibody∗ [46] | 54 (44–63) | 98 (96–100) |

| Repetitive nerve stimulation [47] | 26 (15–44) | 95 (94–100) |

| SFEMG [48] | 89 (83–95) | 88 (78–96) |

Note: These figures were calculated from the table in the article entitled ‘A systematic review of diagnostic studies in myasthenia gravis’ [49]. Benatar assessed the quality of the studies as well as the reported results of sensitivity and specificity. The individual figures from each of the studies quoted were summed and divided by the number of studies to obtain the sensitivity, specificity and 95% confidence intervals quoted in this table.

∗The figures for the ACHR antibody assay are at variance with the accepted figure of approximately 85% sensitivity [50] and the explanation for this is unclear.

THE TENSILON TEST: The tensilon (edrophonium hydrochloride) test demonstrates transient improvement lasting 30–60 seconds.

1. The patient should be pre-treated with atropine 600 μg to reduce the gastrointestinal side effects of the edrophonium hydrochloride.

2. 10 mg of edrophonium is mixed with 9 mL of normal saline (1 mg of edrophonium per mL).

3. Initially 2 mg is injected; if the patient fails to respond to 2 mg, the other 8 mg is injected.

4. Observe the patient for at least 3 minutes after the injection (longer in older patients due to a slower circulation time).

In some patients 2 mg is too much and in other patents 8 mg may be insufficient [51]. In normal patients the tensilon test does not produce any change in strength.

ACETYLCHOLINE RECEPTOR ANTIBODIES: Acetylcholine receptor (ACHR) antibodies are positive in 85% of patients with myasthenia gravis [50]. ACHR antibodies may be detected with repeat testing in some patients with myasthenia gravis in whom they are initially negative [52]. It is likely that further antibodies will be discovered in the sero-negative (the ACHR antibody negative) patients with myasthenia gravis.

Musk antibodies are an IgG antibody against the muscle-specific kinase (MuSK). The presence of antibodies against MuSK appears to define a subgroup of patients with sero-negative myasthenia gravis who have predominantly localised, in many cases bulbar, muscle weaknesses (face, tongue, pharynx etc) and reduced response to conventional immunosuppressive treatments [53].

Anti-titin antibodies may identify patients with a thymoma [39].

NERVE CONDUCTION STUDIES: Nerve conduction studies can differentiate between myasthenia gravis and Lambert–Eaton syndrome.

A repetitive stimulation study is where the nerve is stimulated at 3 per second for 8 impulses immediately before exercise, 20 seconds after sustained exercise and then at intervals of 1 minute for several minutes. The test may demonstrate a decremental response (the 5th response is of lower amplitude compared to the 1st response) in patients with myasthenia gravis and an incremental response in patients with the Lambert–Eaton syndrome.

CHRONIC FATIGUE OR POST-VIRAL FATIGUE SYNDROME

The post-viral fatigue syndrome is very common. It was initially described at the Royal Free Hospital [59] and was referred to as benign myalgic encephalomyelitis [60]. The aetiology remains obscure, although a similar syndrome of fatigue and depression is common following infectious mononucleosis [61], suggesting a possible viral aetiology and thus the term post-viral fatigue syndrome.

Although post-viral fatigue can occur in epidemics, it is usually sporadic. It occurs at any age but is more common in young and middle-aged females. The overwhelming complaint is one of severe fatigue with muscle aches and pains developing after a flu-like illness. Depression and excessive sleep are common, as are complaints of poor memory and difficulty concentrating [62].

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

Currently the diagnosis is based on the clinical features, the results of MRI, analysis of the cerebral spinal fluid and visual evoked potentials [63] (see Tables 14.2–14.4). These criteria have been modified on several occasions and are likely to change in the future. The diagnosis of MS can be very difficult as there are a number of conditions that can result in multifocal involvement of the central nervous system and thus mimic MS. These include central nervous system or systemic vasculitis including systemic lupus erythematosus, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, sarcoidosis, Wilson’s disease, paraneoplastic syndromes and central nervous system lymphoma.

TABLE 14.2

Primary tumours of the nervous system named according to their cell of origin

| Central nervous system | Cell of origin | Name of tumour |

| Astrocytes | Astrocytoma∗ | |

| Ependyma | Ependymoma∗ | |

| Oligodendrocytes | Oligodendrogliomas∗ | |

| Neuroectoderm | Medulloblastoma, pinealoblastoma | |

| Meninges | Meningioma | |

| Schwann cell | Neurofibroma | |

| Peripheral nervous system | ||

| Schwann cell | Neurofibroma | |

| Neuroectoderm | Ewing’s sarcoma |

Note: All these tumours can be either malignant or benign.

∗Astrocytomas, ependymomas and oligodendrogliomas are referred to as gliomas.

TABLE 14.3

Central nervous system paraneoplastic syndromes

| Clinical syndrome | Antibodies | Underlying malignancy |

| Carcinoma-associated retinopathy | Antirational | SCLC, melanoma, gynaecologic |

| Limbic encephalitis | Anti-Hu, anti-Ma2 | SCLC, testicular |

| Brainstem encephalitis | Anti-Ma1, anti-Ma2 | Lung, testicular |

| Encephalomyelitis | Anti-amphiphysin, anti-PCA-2, anti-CRMP5, ANNA-3, anti-NMDA-receptor | SCLC, breast, thymoma, ovarian |

| Cerebellar degeneration | Anti-Yo, anti-Hu, anti-Tr anti-Ma1, anti-mGluR1, anti-PCA-2, anti-CRMP5 | SCLC, ovarian, breast, bladder, Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| Opsoclonus–myoclonus | Anti-Ri | Ovarian, breast, bladder, lung |

| Chorea | Anti-CRMP5 (anti-CV2) | SCLC, breast, thymoma |

| Necrotising myelopathy | None identified | Not specific |

| Stiff-person syndrome | Anti-amphiphysin | SCLC, breast |

Compiled from Darnell and Posner [71], Dalmau [72] and Anderson and Barber [73]

TABLE 14.4

Peripheral nervous system paraneoplastic syndromes

| Clinical syndrome | Antibodies | Underlying malignancy |

| Dorsal root ganglionopathy | Anti-Hu, anti-CRMP5 (anti-CV2), ANNA-3 | Lung, SCLC, thymoma |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Anti-MAG | Waldenstrom’s |

| Autonomic neuropathy | Anti-Hu, anti-nicotinic AchR | SCLC, bladder, thyroid |

| Myasthenia gravis | AchR, anti-titin | Thymoma |

| Lambert–Eaton syndrome | Anti-VGCC, anti-PCA-2 | SCLC |

| Dermatomyositis | None identified | Ovarian, breast, lung |

| Necrotising myopathy | None identified | No specific neoplasm |

| Neuromyotonia | Anti-VGKC | SCLC, thymoma |

| Stiff-person syndrome | Anti-amphiphysin | SCLC, breast |

Compiled from Darnell and Posner [71], Dalmau [72], Rudnicki [74] and Anderson and Barber [73]

MS as it is currently defined is more common in women and in younger patients between the ages of 15 and 50, with a mean age of onset of 29–33 years. It can occur in children or in adults over the age of 50. There is probably a genetic predisposition [64]. The natural history is highly variable from the very benign, where it is accidentally discovered at autopsy in old age, to the very malignant with death within the first few years of onset. This variability makes it very difficult to assess therapeutic interventions. In general, at 10 years 50% of patients with MS will have a neurological deficit requiring the use of a cane to walk while 15% will be in a wheelchair [65].

Presentations of multiple sclerosis

Younger patients with the disease may present with a clinically isolated syndrome affecting the optic nerve, such as optic or retrobulbar neuritis, the spinal cord with transverse myelitis or involvement of the brainstem with vertigo and/or diplopia. The latter relates to involvement of the median longitudinal fasciculus resulting in an internuclear ophthalmoplegia. These episodes are usually self-limiting with resolving over several weeks. The presence of gadolinium-enhancing abnormalities or juxtacortical lesions on an MRI scan increases the risk of progression to clinically definite MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes.

When to suspect multiple sclerosis

OPTIC OR RETROBULBAR NEURITIS

Unilateral blurring of vision associated with pain on movement of the eye evolving over hours to days is a very typical initial presentation and represents optic or retrobulbar neuritis. As described in Chapter 4, ‘The cranial nerves and understanding the brainstem’, patients with optic neuritis will have markedly impaired visual acuity with a swollen optic disc and an afferent pupillary defect with or without impairment of colour vision, whereas patients with retrobulbar neuritis will have the same features but without the optic disc swelling.

TRANSVERSE MYELITIS

It is important to remember that transverse myelitis is a syndrome and not a diagnosis. Although MS is a common cause of transverse myelitis, transverse myelitis also occurs with infectious and post-infectious diseases, as a paraneoplastic phenomenon and in collagen vascular diseases. Patients with transverse myelitis and a normal MRI scan of the brain have a low risk of developing clinically definite MS [66].

NEUROMYELITIS OPTICA

The term neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is used to describe an entity where severe attacks of optic neuritis and transverse myelitis occur either simultaneously or in succession. Although a monophasic form exists, the tendency is for recurrent optic neuritis and transverse myelitis. The original description was of transverse myelitis with bilateral optic neuritis or bilateral retrobulbar neuritis. MS, systemic lupus erythematosus, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and Behçet’s can present with clinical features resembling NMO. Some authorities regard NMO as a distinct disorder separate from MS [67]. On MRI there are extensive longitudinal central spinal cord T2 lesions over several segments. Oligoclonal bands are usually negative in the cerebral spinal fluid and 70% will have a unique biomarker in the serum, the NMO-IgG or aquaporin [67]. In contrast, in patients with MS the spinal cord abnormality on MRI usually involves fewer than two segments, is asymmetrical and in the peripheral aspect of the spinal cord. Patients with NMO often succumb to respiratory failure. The pathogenesis of NMO is likely to be different to that of MS.

Investigation in suspected multiple sclerosis

MRI has revolutionised the management of patients with MS, both in terms of diagnosis and also as a surrogate endpoint in therapeutic trials. The current McDonald criteria [63] used for the diagnosis of MS rely heavily on the MRI scan findings. The criteria are given in Appendix I.

MALIGNANCY AND THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

Direct effects of malignancy

PRIMARY TUMOURS OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

Primary tumours of the nervous system can affect the brain, spinal cord or rarely the peripheral nervous system and they are named according to their cell of origin (see Table 14.2). Tumours can develop from:

Classifications of tumours of the nervous system, such as that of the World Health Organization [68, 69], will continue to evolve with new discoveries [70].

Primary central nervous system tumours declare themselves with seizures, headache or the development of a progressive focal neurological deficit. Gliomas can affect any part of the nervous system but are less common in the brainstem or spinal cord. They can infiltrate the corpus collosum, spreading to both hemispheres and forming a butterfly glioma, or they can infiltrate throughout the entire brain rather than forming a discrete mass and this is referred to as gliomatosis cerebri.

1. a direct result of the tumour (visual loss due to compression of the optic chiasm or optic nerves and headache)

2. destruction of the pituitary gland and loss of hormone function, in particular hypothyroidism and amenorrhoea

3. excess hormone secretion, e.g. growth hormone causing either gigantism or acromegaly or prolactin causing galactorrhoea.

Secondary tumours of the nervous system

In non-central nervous system malignancy the neurological manifestations may be the presenting symptom of that malignancy or they may develop in a patient with an established diagnosis. Any tumour can potentially metastasise to the brain, but the common ones are lung and breast, while the paired organs (thyroid, lung, breast, kidney and prostate) metastasise to the spinal column. Secondaries tend to occur in patients between the ages of 40 and 60. Spinal cord compression due to malignancy is discussed in Chapter 13, ‘Abnormal movements and difficulty walking due to central nervous system problems’.

Paraneoplastic syndromes

Paraneoplastic syndromes refer to neurological symptoms and signs in a patient with malignancy that are not the direct result of the tumour but rather an immune-mediated remote effect. Paraneoplastic syndromes are seen in both the central and peripheral nervous systems (see Tables 14.3 and 14.4). Similar clinical syndromes mediated by antibodies may also be seen in the absence of malignancy. Anti-neuronal antibodies that react with the underlying tumour and the target cells within the central nervous system can be detected [71–74].

These neurological syndromes are very severe, often disabling and sometimes fatal. They can develop rapidly over days but more commonly weeks to a few months. The neurological symptoms and signs often but not invariably precede the diagnosis of malignancy for months and sometimes years; in other patients they may herald a recurrence of the tumour. The malignancy may initially elude detection, despite extensive investigations and be diagnosed some time later. It is thought that effective antitumour immunity is associated with autoimmune brain disease [71, 75–81]. Increasing numbers of antibodies are being recognised and the type of malignancy can vary considerably; the ones listed in the tables are the more common (see Tables 14.3 and 14.4). It is now recognised that pure presentations of these syndromes are the exception rather than the rule and it is not uncommon for a patient with malignancy and paraneoplastic phenomena to have multifocal symptoms and signs.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is able to detect malignancy even in patients where a CT scan is negative. In patients with paraneoplastic syndromes, PET scanning has a sensitivity and specificity of 80% and 67%, respectively [82].

Self-examination, mammography, ultrasound, MRI and a new modality termed elasticity imaging are all used to detect breast cancer [83].

Complications of therapy

COMPLICATIONS OF CHEMOTHERAPY

The most common side effect of chemotherapeutic agents is peripheral neuropathy [84, 85]. The neuropathy is dose-dependent, develops gradually and increases in severity with subsequent doses. It is almost invariably a length-dependent peripheral neuropathy in which patients develop a distal sensory loss in the lower limbs with or without distal weakness. Very rarely the autonomic nervous system may be affected, for example with vincristine. Oxaliplatin has been reported to cause an acute reversible peripheral neuropathy developing within hours of commencing intravenous therapy [86]. Improvement often but not invariably occurs if no further doses are given, although this may be unavoidable in order to treat the malignancy. Peripheral neuropathy is seen with many of the currently employed chemotherapeutic agents, including thalidomide and an analogue of thalidomide, lenalidomide, the vinca alkaloids (vincristine and vinblastine), platinum compounds (cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin), the taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel) and cytarabine.

Cognitive decline may occur with chemotherapy and is referred to as ‘chemobrain’ [85].

COMPLICATIONS OF INTRATHECAL THERAPY

Occasionally drugs, for example methotrexate and cytarabine, are administered via the intrathecal route (into the cerebral spinal fluid via a lumbar puncture). This route of administration can be complicated by chemical meningitis, myelopathy (spinal cord involvement) or seizures Multifocal leucoencephalopathy has been reported with capecitabine [87]. The inadvertent intrathecal administration of vincristine causes a severe myelopathy with tetraplegia that is often fatal [88].

COMPLICATIONS OF RADIOTHERAPY

The neurological complications of radiotherapy can be divided into early and delayed [89]. The early complications are usually mild and transient whereas the delayed complications are often progressive and disabling. Complications occur when central nervous system tumours are irradiated or as a result of incidental damage when the radiation is applied to soft tissue tumours adjacent to the nervous system. The site of the neurological complications will relate directly to the site of radiotherapy. Necrosis resulting in swelling and a mass effect may occur with radiation to the brain. The onset of symptoms usually commences 1–3 years after therapy but may begin as early as 3 months or be delayed for as long as 12 years. The symptoms and signs relate to the mass. At times it can be difficult to differentiate between recurrent tumour and radiation necrosis. Radiation necrosis-induced masses may also, like tumours, enhance with contrast on a CT scan of the brain. Careful correlation with the sight of maximum irradiation may sometimes help to differentiate recurrent tumour from radiation necrosis. MR spectroscopy or computer-assisted stereotactic biopsy is used to differentiate tumour recurrence from radiation necrosis [90, 91].

Non-reversible radiation myelopathy can occur acutely, with paraplegia or quadriplegia evolving over days and is thought to relate to arterial occlusion [92]. This acute form of myelopathy is very rare and more common is the chronic progressive myelopathy developing within 1 year, although it may occur as early as 4 months or as late as 13 years after radiation. The patient develops ascending sensory loss and weakness often associated with sphincter disturbance. The symptoms and signs are usually bilateral but may be unilateral. The myelopathy progresses over months, often to severe disability. An MRI scan demonstrates swelling of the spinal cord, focal contrast enhancement, low signal over several segments on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images [93, 94].

There is little effective treatment for radiation damage to the nervous system. Treatment with corticosteroids, surgery or antioxidants is often ineffective and the role of anticoagulation remains unclear [95, 96].

INFECTIONS OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

Meningitis, which is one of the more common infections of the nervous system, has already been discussed in Chapter 9, ‘Headache and facial pain’. Central nervous system infections, particularly opportunistic infections, are more common in immunocompromised patients such as patients with HIV or those on immunosuppressive therapy. A complete discussion of central nervous system infections is beyond the scope of this book.

Encephalitis

Encephalitis literally means inflammation of the brain. Many patients also have associated meningitis and often the term meningo-encephalitis is used. A complete review is beyond the scope of this book. It can occur in HIV, related to malignancy, as a paraneoplastic a phenomena (Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis) or secondary to viral infection. Viral encephalitis can occur either in epidemics (e.g. Murray–Valley or Japanese encephalitis) or it can be sporadic with the commonest cause being herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE). The essential clinical features are fever, confusion, focal or generalised seizures, focal neurological signs, signs of meningism and often impairment of consciousness.

HERPES SIMPLEX ENCEPHALITIS

Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) is seen sporadically and is probably the commonest form of encephalitis encountered in clinical practice. Left untreated it can either be fatal or result in a devastating neurological deficit, in particular with regards to memory. Untreated the mortality approaches 70% and only 10% of patients can return to a normal life [97]. The advent of effective therapy (see below) has reduced mortality to approximately 20% [97], although rates as low as 7% have been reported [98]. A poor outcome still occurs in 30–40% of patients [98].

Approach to immunocompromised patients with disorders of the central nervous system

Human (HIV) or acquired immune deficiency (AIDS) virus results in severe immune deficiency, but immune deficiency is more commonly seen in patients with malignancy on chemotherapy and with immune-mediated disorders such as vasculitis treated with immunosuppressants. In addition to the typical complications seen in patients who are immunocompromised, HIV also results in a variety of peripheral nervous system complications, in particular a painful peripheral neuropathy, a vacuolar myelopathy and an inflammatory myopathy [106]. Direct invasion of the virus into the central nervous system results in the AIDS dementia complex[107]. These are beyond the scope of this book; please refer to the book entitled AIDS and the Nervous System by Rosenblum, Levy and Bredesen (New York: Raven Press; 1998). In particular Chapter 19 of that book contains excellent algorithms to aid in the management of patients with AIDS and neurological symptoms.

MRI and stereotactic biopsy is the approach to patients with mass lesions who are alert, while open biopsy and decompression is necessary if there is imminent herniation. Analysis of CSF, MRI and empirical treatment for toxoplasmosis is the approach if there are multiple lesions and the patient is alert and stable.

REFERENCES

1. Plum, F., Posner, J.B. Diagnosis of stupor and coma, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1972. [286].

2. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 2003, 10th Revision. 2007. Available: http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/ (14 Dec 2009).

3. Mayo-Smith, M.F., et al. Management of alcohol withdrawal delirium: An evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(13):1405–1412.

4. Attard, A., Ranjith, G., aylor, D. Delirium and its treatment. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(8):631–644.

5. Lonergan, E., et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2009. [CD006379].

6. Reynolds, C.F., 3rd., et al. Bedside differentiation of depressive pseudodementia from dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(9):1099–1103.

7. Kertesz, A. Clinical features and diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2009;24:140–148.

8. Alladi, S., et al. Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 10):2636–2645.

9. Mesulam, M.M. Primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(4):425–432.

10. Petersen, R.C. Focal dementia syndromes: In search of the gold standard. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(4):421–423.

11. Geschwind, M.D., et al. Rapidly progressive dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(1):97–108.

12. Pokorski, R.J. Differentiating age-related memory loss from early dementia. J Insur Med. 2002;34(2):100–113.

13. Linn, R.T., et al. The ‘preclinical phase’ of probable Alzheimer’s disease: A 13-year prospective study of the Framingham cohort. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(5):485–490.

14. Meyer, J.S., Huang, J., Chowdhury, M.H. MRI confirms mild cognitive impairments prodromal for Alzheimer’s, vascular and Parkinson–Lewy body dementias. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257(1–2):97–104.

15. Jackson CE. A clinical approach to muscle diseases. Semin Neurol 2008 Apr. Available: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/572269 (28 Feb 2009).

16. Washington University. Myopathy and neuromuscular junction disorders: Differential diagnosis. Available: http://neuromuscular.wustl.edu/maltbrain.html (3 Jul 2009).

17. Karpati, G., Hilton-Jones, D., Griggs, R.D. Disorders of voluntary muscle, 7th edn. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

18. Mendell, J.R. Approach to the patient with muscle disease. In: Hauser S.L., ed. Harrison’s neurology in clinical medicine. San Francisco: McGraw–Hill, 2006.

19. Klopstock, T. Drug-induced myopathies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21(5):590–595.

20. Klinge, L., et al. New aspects on patients affected by dysferlin deficient muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 14 Jun 2009. [[Epub ahead of print]].

21. Norwood, F., et al. EFNS guideline on diagnosis and management of limb girdle muscular dystrophies. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(12):1305–1312.

22. Hilton-Jones, D., Kissel, J.T. The examination and investigation of the patient with muscle disease. In: Karpati G., Hilton-Jones D., Griggs R., eds. Disorders of voluntary muscle. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001:349–373.

23. Moxley, R.T., 3rd., et al. Practice parameter: Corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne dystrophy: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2005;64(1):13–20.

24. Choy, E.H., et al. Immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory treatment for dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2005. [CD003643].

25. Wiendl, H. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: Current and future therapeutic options. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5(4):548–557.

26. Fries, J.F., et al. Cyclophosphamide therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus and polymyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 1973;16(2):154–162.

27. Vencovsky, J., et al. Cyclosporine A versus methotrexate in the treatment of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2000;29(2):95–102.

28. Miller, F.W., et al. Controlled trial of plasma exchange and leukapheresis in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(21):1380–1384.

29. Dalakas, M.C., et al. A controlled trial of high-dose intravenous immune globulin infusions as treatment for dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(27):1993–2000.

30. Elovaara, I., et al. EFNS guidelines for the use of intravenous immunoglobulin in treatment of neurological diseases: EFNS task force on the use of intravenous immunoglobulin in treatment of neurological diseases. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(9):893–908.

31. Oldfors, A., Lindberg, C. Diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment of inclusion body myositis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18(5):497–503.

32. Greenberg, S.A. Inclusion body myositis: Review of recent literature. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009;9(1):83–89.

33. Phillips, P.S., et al. Statin-associated myopathy with normal creatine kinase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(7):581–585.

34. Sailler, L., et al. Increased exposure to statins in patients developing chronic muscle diseases: A 2-year retrospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(5):614–619.

35. Willis, T. De anima brutorum. Oxford: Oxonii Theatro Sheldoniano; 1672. [404–407].

36. Eaton, L.M., Lambert, E.H. Electromyography and electric stimulation of nerves in diseases of motor unit: Observations on myasthenic syndrome associated with malignant tumors. J Am Med Assoc. 1957;163(13):1117–1124.

37. Mulder, D.W., Lambert, E.H., Eaton, L.M. Myasthenic syndrome in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1959;9:627–631.

38. Hoch, W., et al. Auto-antibodies to the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK in patients with myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Nat Med. 2001;7(3):365–368.

39. Aarli, J.A., et al. Patients with myasthenia gravis and thymoma have in their sera IgG autoantibodies against titin. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;82(2):284–288.

40. Kennedy, W.R., Jimenez-Pabon, E. The myasthenic syndrome associated with small cell carcinoma of the lung (Eaton–Lambert syndrome). Neurology. 1968;18(8):757–766.

41. Gutmann, L., et al. The Eaton–Lambert syndrome and autoimmune disorders. Am J Med. 1972;53(3):354–356.

42. Ackerman, L.V., et al. Thymoma in a case of myasthenia gravis. Mo Med. 1949;46(4):270–272.

43. Sethi, K.D., Rivner, M.H., Swift, T.R. Ice pack test for myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 1987;37(8):1383–1385.

44. Larner, A.J., Thomas, D.J. Can myasthenia gravis be diagnosed with the ‘ice pack test’? A cautionary note. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76(893):162–163.

45. Osserman, K.E., Kaplan, L.I. Rapid diagnostic test for myasthenia gravis: Increased muscle strength, without fasciculations, after intravenous administration of edrophonium (tensilon) chloride. JAMA. 1952;150(4):265–268.

46. Aharonov, A., et al. Humoral antibodies to acetylcholine receptor in patients with myasthenia gravis. Lancet. 1975;2(7930):340–342.

47. Schwartz, M.S., Stalberg, E. Single fibre electromyographic studies in myasthenia gravis with repetitive nerve stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975;38(7):678–682.

48. Stalberg, E., Ekstedt, J., Broman, A. Neuromuscular transmission in myasthenia gravis studied with single fibre electromyography. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1974;37(5):540–547.

49. Benatar, M. A systematic review of diagnostic studies in myasthenia gravis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16(7):459–467.

50. Vincent, A., et al. Antibodies in myasthenia gravis and related disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;998:324–335.

51. Osserman, K.E., Genkins, G. Critical reappraisal of the use of edrophonium (tensilon) chloride tests in myasthenia gravis and significance of clinical classification. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1966;135(1):312–334.

52. Vincent, A., Newsom-Davis, J. Acetylcholine receptor antibody as a diagnostic test for myasthenia gravis: Results in 153 validated cases and 2967 diagnostic assays. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48(12):1246–1252.

53. Vincent, A., et al. Seronegative generalised myasthenia gravis: Clinical features, antibodies, and their targets. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(2):99–106.

54. Sonett, J.R., Jaretzki, A., 3rd. Thymectomy for nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis: A critical analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1132:315–328.

55. Walker, M.B. Treatment of myasthenia gravis with physostigmine. Lancet. 1934;1:1200–1201.

56. Schneider-Gold, C., et al. Corticosteroids for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2005. [CD002828].

57. Hart, I.K., Sathasivam, S., Sharshar, T. Immunosuppressive agents for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2007. [CD005224].

58. Maddison, P., Newsom-Davis, J. Treatment for Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2003. [CD003279].

59. Ramsay, A.M., O’Sullivan, E. Encephalomyelitis simulating poliomyelitis. Lancet. 1956;270(6926):761–764.

60. Galpine, J.F., Brady, C. Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis. Lancet. 1957;272(6972):757–758.

61. Petersen, I., et al. Risk and predictors of fatigue after infectious mononucleosis in a large primary-care cohort. Q J Med. 2006;99(1):49–55.

62. Behan, P.O., Bakheit, A.M. Clinical spectrum of postviral fatigue syndrome. Br Med Bull. 1991;47(4):793–808.

63. Polman, C.H., et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria”. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(6):840–846.

64. Ebers, G.C., et al. A population-based study of multiple sclerosis in twins. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(26):1638–1642.

65. Courtney, A.M., et al. Multiple sclerosis. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(2):451–476. [ix–x].

66. Scott, T.F., Kassab, S.L., Singh, S. Acute partial transverse myelitis with normal cerebral magnetic resonance imaging: Transition rate to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(4):373–377.

67. Weinshenker, B.G. Neuromyelitis optica is distinct from multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(6):899–901.

68. Brat, D.J., et al. Surgical neuropathology update: A review of changes introduced by the WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system, 4th edn. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132(6):993–1007.

69. Louis, D.N., et al. WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system, 4th edn. Lyon: France: IARC Press; 2007.

70. Rousseau, A., Mokhtari, K., Duyckaerts, C. The 2007 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system – what has changed? Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21(6):720–727.

71. Darnell, R.B., Posner, J.B. Paraneoplastic syndromes involving the nervous system. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(16):1543–1554.

72. Dalmau, J., et al. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: Case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(12):1091–1098.

73. Anderson, N.E., Barber, P.A. Limbic encephalitis – a review. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15(9):961–971.

74. Rudnicki, S.A., Dalmau, J. Paraneoplastic syndromes of the spinal cord, nerve, and muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23(12):1800–1818.

75. Posner, J.B., Dalmau, J. Paraneoplastic syndromes. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9(5):723–729.

76. Bennett, J.L., et al. Neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations of a paraneoplastic syndrome and testicular carcinoma. Neurology. 1999;52(4):864–867.

77. Saiz, A., et al. Anti-Hu-associated brainstem encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(4):404–407.

78. Chiang, Y.Z., Tjon Tan, K., Hart, I.K. Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2009;70(3):168–169.

79. Duddy, M.E., Baker, M.R. Stiff person syndrome. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2009;26:147–165.

80. Ferreyra, H.A., et al. Management of autoimmune retinopathies with immunosuppression. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(4):390–397.

81. Mehta, S.H., Morgan, J.C., Sethi, K.D. Paraneoplastic movement disorders. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009;9(4):285–291.

82. Hadjivassiliou, M., et al. PET scan in clinically suspected paraneoplastic neurological syndromes: A 6-year prospective study in a regional neuroscience unit. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;119(3):186–193.

83. Sarvazyan, A., et al. Cost-effective screening for breast cancer worldwide: Current state and future directions. Breast Cancer. 2008;1:91–99.

84. Young, D.F. Neurological complications of cancer chemotherapy. In: Silverstein A., ed. Neurological complications of therapy. New York: Futura Publishing; 1982:57–113.

85. Kannarkat, G., Lasher, E.E., Schiff, D. Neurologic complications of chemotherapy agents. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20(6):719–725.

86. Grolleau, F., et al. A possible explanation for a neurotoxic effect of the anticancer agent oxaliplatin on neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85(5):2293–2297.

87. Jabbour, E., et al. Neurologic complications associated with intrathecal liposomal cytarabine given prophylactically in combination with high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine to patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109(8):3214–3218.

88. Schochet, S.S., Jr., Lampert, P.W., Earle, K.M. Neuronal changes induced by intrathecal vincristine sulfate. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1968;27(4):645–658.

89. Berger, P.S. Neurological complications of radiotherapy. In: Silverstein A., ed. Neurological complications of therapy. New York: Futura Publishing; 1982:137–185.

90. Schlemmer, H.P., et al. Differentiation of radiation necrosis from tumor progression using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuroradiology. 2002;44(3):216–222.

91. Forsyth, P.A., et al. Radiation necrosis or glioma recurrence: Is computer-assisted stereotactic biopsy useful? J Neurosurg. 1995;82(3):436–444.

92. Di Chiro, G., Herdt, J.R. Angiographic demonstration of spinal cord arterial occlusion in postradiation myelomalacia. Radiology. 1973;106(2):317–319.

93. de Toffol, B., et al. Chronic cervical radiation myelopathy diagnosed by MRI. J Neuroradiol. 1989;16(3):251–253.

94. Wang, P.Y., Shen, W.C., Jan, J.S. Serial MRI changes in radiation myelopathy. Neuroradiology. 1995;37(5):374–377.

95. Glantz, M.J., et al. Treatment of radiation-induced nervous system injury with heparin and warfarin. Neurology. 1994;44(11):2020–2027.

96. Happold, C., et al. Anticoagulation for radiation-induced neurotoxicity revisited. J Neurooncol. 2008;90(3):357–362.

97. Herpes simplex encephalitis. Lancet, 1986. [1(8480):535–536].

98. Shoji, H. Can we predict a prolonged course and intractable cases of herpes simplex encephalitis? Intern Med. 2009;48(4):177–178.

99. Dutt, M.K., Johnston, I.D. Computed tomography and EEG in herpes simplex encephalitis: Their value in diagnosis and prognosis. Arch Neurol. 1982;39(2):99–102.

100. Schroth, G., et al. Early diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis by MRI. Neurology. 1987;37(2):179–183.

101. Al-Shekhlee, A., Kocharian, N., Suarez, J.J. Re-evaluating the diagnostic methods in herpes simplex encephalitis. Herpes. 2006;13(1):17–19.

102. Domingues, R.B., et al. Diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis by magnetic resonance imaging and polymerase chain reaction assay of cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol Sci. 1998;157(2):148–153.

103. Whitley, R.J., Roizman, B. Herpes simplex virus infections. Lancet. 2001;357(9267):1513–1518.

104. Kamei, S., et al. Evaluation of combination therapy using aciclovir and corticosteroid in adult patients with herpes simplex virus encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(11):1544–1549.

105. Openshaw, H., Cantin, E.M. Corticosteroids in herpes simplex virus encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(11):1469.

106. Price, R.W. Neurological complications of HIV infection. Lancet. 1996;348(9025):445–452.

107. Clifford, D.B. AIDS dementia. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86(3):537–550. [vi].

1In the majority of patients with myasthenia gravis, antibodies are directed against the acetylcholine receptor, although in recent years other antibodies have been identified [38, 39]. The Lambert–Eaton syndrome is due to antibodies directed against the P/Q-type calcium channels at the motor nerve terminals.