Miscellaneous Cervical Neoplasms

Epithelial Tumors

Adenoid Basal Carcinoma (Adenoid Basal Epithelioma)

Definition

Adenoid basal carcinoma (adenoid basal epithelioma) is composed of bland, uniform, basaloid cells arranged in nests with a variable amount of glandular and squamous differentiation.1 Based on their favorable outcome, there is a proposal to designate this tumor as ‘epithelioma,’ rather than carcinoma.1,2

General Features

Adenoid basal carcinoma (epithelioma) accounts for less than 1% of cervical cancers and usually develops in postmenopausal women with a median age of 66.5 years and a wide age range, from 19 to 91 years.2,3 Most patients are asymptomatic and the tumor is frequently an incidental finding in a surgical specimen obtained after the diagnosis of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion on a Pap smear. In rare cases, patients can complain of vaginal bleeding, hematuria, or dysuria.1,2 The tumor appears to arise from reserve cells and is usually associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) 16.2

Pathology

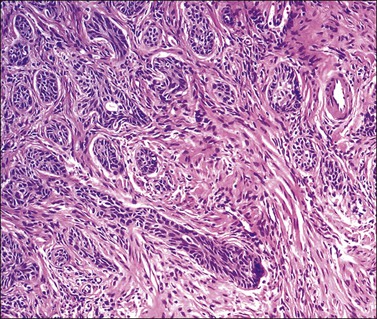

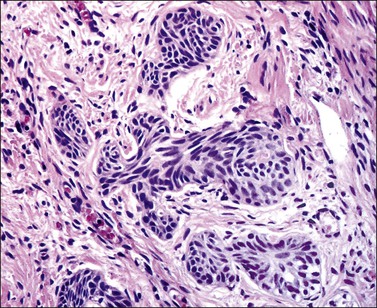

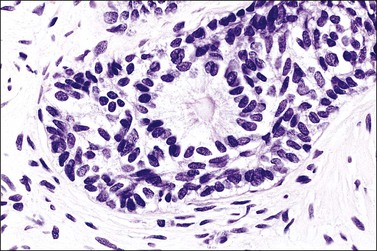

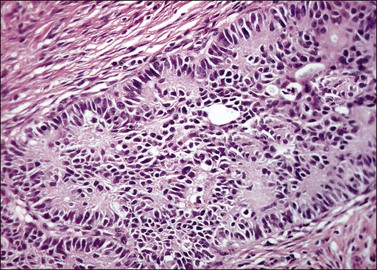

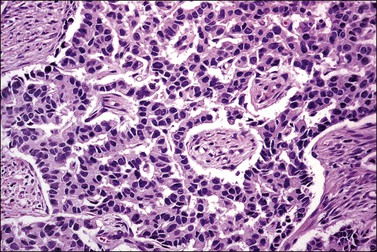

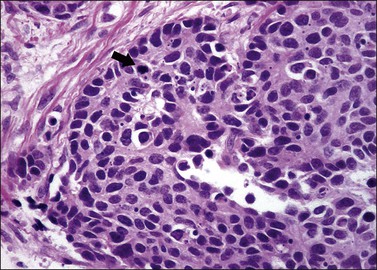

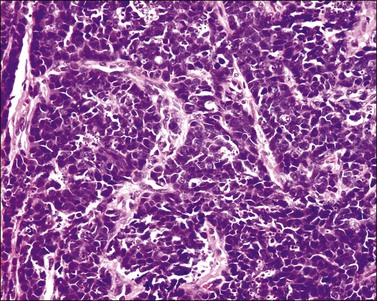

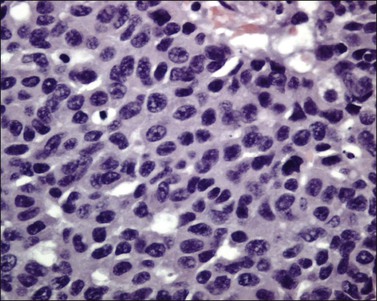

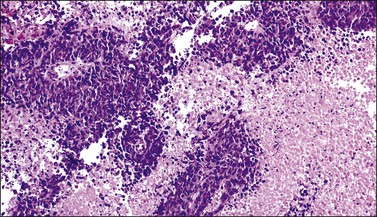

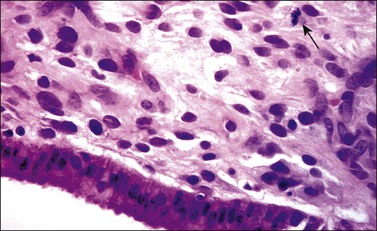

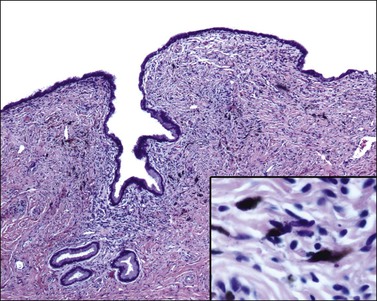

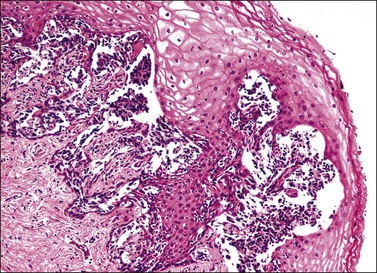

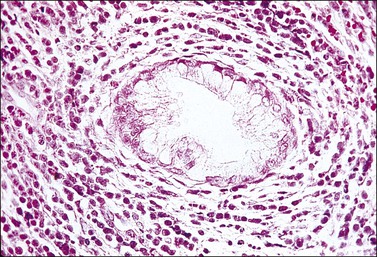

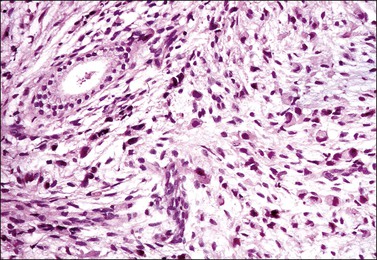

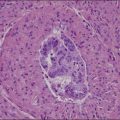

Grossly, the tumor is usually invisible; however, induration, erosion, ulceration, and abnormalities of the cervical mucosa have been described in rare cases.2 Adenoid basal carcinoma (epithelioma) is composed of multiple, small, round to oval nests of bland, uniform, basaloid cells with peripheral palisading (Figures 13.1 and 13.2). The tumor nests are haphazardly distributed in the cervical stroma without eliciting a desmoplastic response although focal edema and mild chronic inflammation may be seen.1 The tumor typically does not reach the surface of the endocervical canal; however, occasionally it appears in continuity with an overlying dysplastic squamous epithelium.4 Clearing of the cytoplasm due to the accumulation of glycogen may be seen.5 There is a variable degree of glandular and squamous differentiation (Figure 13.3). The former is characterized by the presence of columnar or cuboidal cells with bland nuclei surrounding a distinct lumen while the latter shows bland squamous cells in the center of the nests with preservation of a peripheral rim of basaloid cells. Occasionally, a cribriform pattern can be noted. The mitotic index is usually low, although it may vary from 0 to 9 mitoses per 10 high power fields (HPFs). There is no necrosis or lymphovascular or perineural invasion.1,4 Although the tumor is typically associated with a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, rarely, it can be associated with a superficially or frankly invasive squamous carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, or carcinosarcoma.3–6

Immunohistochemistry

Adenoid basal carcinoma (epithelioma) is usually immunoreactive for keratin AE1/AE3, CK902 (against cytokeratin 8 and 18), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CAM 5.2, p16, p53, and p63. S-100 can be positive in a few cases.2 A limited number of cases of adenoid basal carcinoma (epithelioma) has been tested for CD117 (c-kit) and found to be negative.7

Differential Diagnosis

Squamous carcinoma can represent a diagnostic difficulty since adenoid basal carcinoma (epithelioma) can have florid squamous metaplasia with marked expansion of the tumor nests, thus mimicking an invasive squamous carcinoma. In addition, focal dysplastic changes can be noted in the areas of squamous metaplasia. Recognition of a residual rim of bland basaloid cells, which can be highlighted with the use of CAM 5.2 immunoreaction, will facilitate the proper identification of adenoid basal carcinoma (epithelioma) with extensive squamous metaplasia.3

Basaloid squamous carcinoma, a rare type of cervical tumor, usually produces a symptomatic tumor mass.8 Microscopically, this tumor is composed of moderately pleomorphic, basaloid cells arranged in nests and cords. There is also peripheral palisading. Mitotic activity and necrosis are conspicuous. Larger cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm as well as a cribriform pattern can be seen. Hyalinization or myxoid change of the stroma is also common.9

Clinical Behavior and Management

Morphologically pure adenoid basal carcinomas (epitheliomas) behave in a benign fashion without metastases to lymph nodes or other sites, local recurrences, or death.2,3 Microscopic examination of the entire tumor is necessary to exclude the presence of an associated neoplasm that could have an adverse impact on the prognosis. Cases of morphologically pure adenoid basal carcinoma (epithelioma) are treated with a loop electrosurgical excision procedure or cold knife cone with negative margins. In cases where the neoplasm extends to the margins, a comment should be included in the report about the possible association with another tumor type that could affect the prognosis.

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

General Features

This tumor is rare and mostly seen in postmenopausal women (mean age, 72 years),4 but it is occasionally detected in younger women in the third or fourth decades of life.10,11 Uterine bleeding is the most common presentation with a rare case diagnosed incidentally.4 This neoplasm appears to originate from reserve cells and is usually associated with HPV 16.5,12

Pathology Features

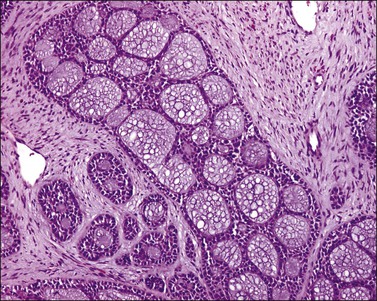

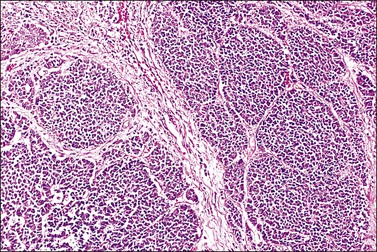

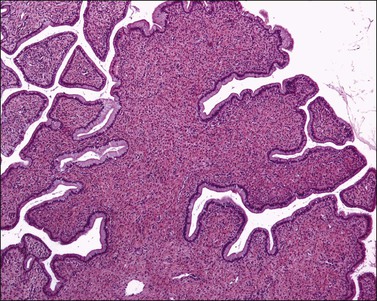

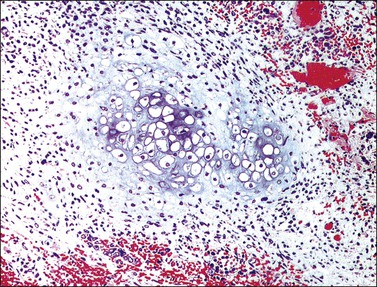

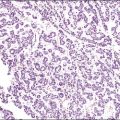

The tumor has a variable appearance from small polypoid lesions to large exophytic, friable masses or deeply invasive endophytic tumors.4 Microscopically, it is composed of mildly pleomorphic basaloid cells arranged in nests, sheets, cords, and trabeculae. Clear cell changes may be present.5 A distinct cribriform pattern containing either an amorphous hyaline eosinophilic basement membrane-like material or basophilic mucinous or eosinophilic secretion is usually seen (Figure 13.4). Mitotic activity is variable, ranging from scanty to very high.4,5 Necrosis is often present and extensive. Stromal changes are typically prominent, ranging from hyalinization to myxoid or fibroblastic change. The solid variant lacks the typical cribriform pattern, but the tumor is recognized by the presence of abundant periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive basement membrane material around the tumor cells that grow in solid nests, cords, and trabeculae.13 Small foci of squamous differentiation may be seen. Adenoid cystic carcinoma can be associated with adenoid basal carcinoma (epithelioma), in situ or invasive squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, or adenocarcinoma.5,11 Adenoid cystic carcinoma tends to involve lymphovascular spaces and develops lymph node metastasis early.11

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor cells are reactive for wide spectrum cytokeratin (CK), CAM 5.2, and EMA. S-100 protein reactivity occurs in some cases5 while others are unreactive or just focally and weakly reactive.4,13 A rare case of cervical adenoid cystic carcinoma has been tested for CD117 (c-kit) and was found to be strongly reactive in approximately 5% of the cells. This finding does not compare with the common expression of CD117 (c-kit) in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands, which is seen in 80–100% of cases.7

Clinical Behavior and Management

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is an aggressive tumor. In one series, nearly half of the patients died of local recurrence or metastatic disease within 8 months to 8 years of diagnosis.4 Treatment options include radiotherapy, surgery, surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy, or chemotherapy.11

Neuroendocrine Tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors of the uterine cervix are rare.14 According to the nomenclature system proposed in 1997 by the College of American Pathologists and the National Cancer Institute, they are classified as typical (classic) carcinoid tumors, atypical carcinoid tumors, small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas.15 These tumors may originate from cells containing neuroendocrine granules, seen in 20% of normal cervices, or from reserve cells.16–18

Additionally, an association with HPV 18 or 16 has been described in atypical carcinoids, small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.17,18,20–22

Typical (Classic) Carcinoid Tumor

The least common of the neuroendocrine tumors14,17 is composed of uniform cells forming nests, trabeculae, cords, or glands. The chromatin is finely granular. Mitoses are rare (at the most 3 mitoses per 10 HPFs) and there is no necrosis (Figure 13.5).23 Immunohistochemical studies show that the tumor cells are positive for neuroendocrine markers such as neuron-specific enolase, CD56, chromogranin, or synaptophysin.

Atypical Carcinoid Tumor

The second least common of the neuroendocrine tumors14,17 is distinguished from the typical (classic) carcinoid on the basis of a mitotic index above 3 mitoses per 10 HPFs (but fewer than 10 mitoses per 10 HPFs) and/or necrosis, usually comedo-type (Figures 13.6 and 13.7).23 Immunohistochemical studies show that the tumor cells are positive for the neuroendocrine markers listed above. Similarly to the typical carcinoid tumor, the experience with atypical carcinoid tumor of the cervix is limited. Therefore, its behavior and optimal treatment are undetermined.

Small Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma

General Features

This tumor accounts for less than 5% of the cervical carcinomas;24 however, it represents the most frequent neuroendocrine neoplasm of the uterine cervix.14 Patients’ ages range from 20 to 87 years (mean, 45 years).19,24,25 Vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom followed by pain.25,26 A rare case has been detected in an abnormal Pap smear.27 Occasionally, patients have developed paraneoplastic syndromes, including Cushing’s syndrome, hypoglycemia, inappropriate antidiuretic hormone production, carcinoid syndrome, and Eaton–Lambert syndrome.19,27–29 Most tumors are International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I or II.19,24,25

Pathology

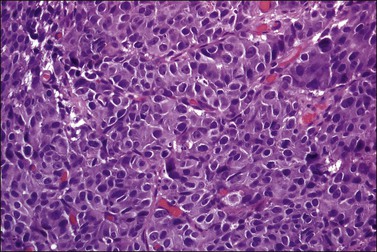

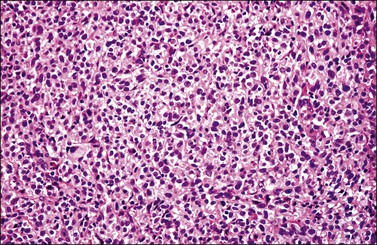

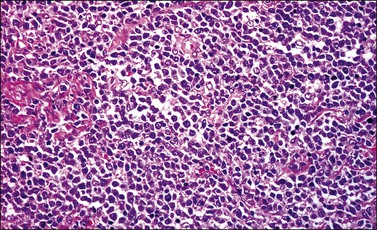

Tumors range in size from 1 to 10 cm.24 A rare case has presented in a normal-appearing cervix.27 Microscopically, small cell carcinoma is composed of oval or spindled cells with scanty cytoplasm, dark nuclei, and no apparent nucleoli. The cells are arranged in nests, trabeculae, and cords (Figures 13.8 and 13.9). Focal gland formation can be noted. There are numerous mitoses and apoptotic bodies. Molding of the nuclei, crush artifact, and necrosis are common. Occasionally, deposition of hematoxylin-stained material around vessels walls (Azzopardi phenomenon) is seen. Lymphovascular invasion is commonly seen. Associated large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, in situ or invasive squamous cell carcinoma, or adenocarcinoma may be found.26,27

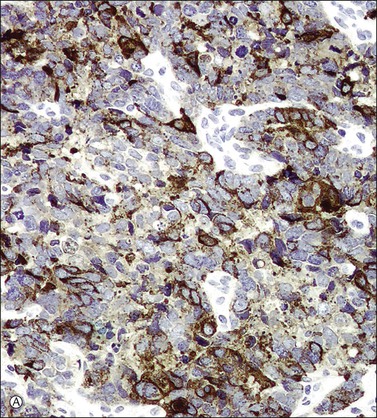

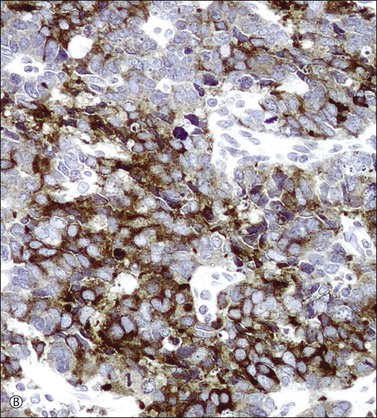

Immunohistochemical Studies

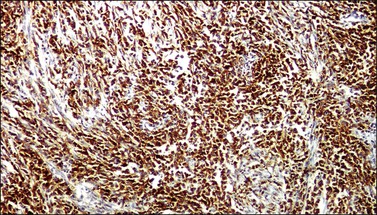

In most cases, the tumor cells express at least one neuroendocrine marker, such as synaptophysin, chromogranin, NSE, or CD5624,30,31 (Figure 13.10A and B). The tumor cells are diffusely positive for p16.32 Up to 87% of the cases are reactive for TTF-1. In addition, the tumor cells may react for keratin 20, neurofilament, and CD99.32 There are conflicting reports on the expression of c-kit in these tumors. Whereas in one study up to 43% of the tumors expressed c-kit,33 only one tumor of another series expressed c-kit diffusely.34

Differential Diagnosis

Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinomas can be composed of small cells with scanty cytoplasm resembling a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. However, squamous carcinoma typically lacks the abundant apoptotic bodies, nuclear molding, and crush artifact that are commonly seen in small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. The use of neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56 will facilitate the correct diagnosis as small cell carcinoma should be positive for at least one of these markers. It should be noted that markers traditionally used to prove squamous differentiation (i.e., p63 and CK 5/6) can be positive in neuroendocrine carcinomas.32,35

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor can share histologic and immunohistochemical features with small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Molecular studies for HPV together with CD99, keratin, and neuroendocrine marker immunoreactions are required to ascertain the correct diagnosis as cervical neuroendocrine carcinomas are HPV associated whereas primitive neuroectodermal tumors are not.32

Clinical Behavior and Management

Small cell carcinoma is an aggressive neoplasm that tends to develop widespread metastases (i.e., bone, liver, lung, lymph nodes, and soft tissue) and has an overall 5 year survival rate of only 29%. Patients with early stage disease are treated with radical hysterectomy. In addition, adjuvant cisplatinum and etoposide-based chemotherapy and radiotherapy are used for distant and local control of the disease. Patients with advanced stage disease are treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy.24

Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma

General Features

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is the second most common type of neuroendocrine tumor of the uterine cervix and accounts for 0.6% of the invasive cervical carcinomas.14,17,36 The mean age of patients is 37 years (age range, 21–75 years).36 The most common symptom is vaginal bleeding, but some tumors are detected as a result of an abnormal Pap smear. The tumors are usually FIGO stage I or II.16,36,37

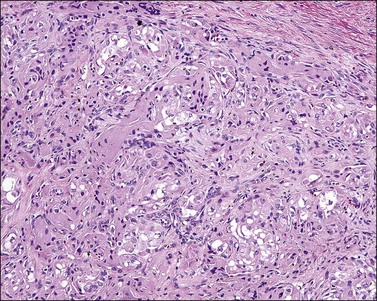

Pathology

The tumor is usually polypoid or exophytic, although it may be ill defined and not even grossly visible. The tumor can be up to 6 cm in greatest dimension and shows a variable cut surface, ranging from tan-brown to yellow-gray or white, with areas of hemorrhage or necrosis.16,37 Microscopically, the tumor cells have a moderate or abundant amount of cytoplasm, moderately or markedly atypical nuclei with vesicular or finely granular chromatin, and visible nucleoli (Figure 13.11). They are arranged in nests, trabeculae, or solid sheets. Glandular formation can be seen (Figure 13.12). The mitotic index is high (more than 10 mitoses per 10 HPFs). Geographic necrosis and lymphovascular invasion are typically present (Figure 13.13). The tumor can be associated with adenocarcinoma in situ, invasive adenocarcinoma (mucinous or endometrioid type), and small cell carcinoma.16,17,37,38

Immunohistochemistry

All tumors express at least one neuroendocrine marker, such as synaptophysin, chromogranin, or CD56. All cases are reactive for p16. The tumor cells can also express TTF-1, p63, keratin 20, neurofilament, and CD99.16,32

Differential Diagnosis

Adenocarcinoma may be erroneously diagnosed due to the presence of focal glandular differentiation in large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, or the association with either an adenocarcinoma in situ or invasive adenocarcinoma. Attention to the architectural patterns (i.e., insular or trabecular) and the presence of geographic necrosis as well as the use of neuroendocrine markers will allow the proper diagnosis. It is important to bear in mind that focal expression of neuroendocrine markers can be seen in an otherwise typical adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma of the uterine cervix.16

Clinical Behavior and Management

The outcome for patients with large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is poor. Survival across all stages is dismal with 67% of patients dying of disease. Intra-abdominal/intrapelvic and distant metastasis, including liver, kidney, adrenal gland, lymph nodes, lung, bone, and brain, are usually seen.16,36,37 Treatment includes surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy.36

Biphasic Tumors

Adenofibroma

This rare neoplasm is composed of benign glands embedded in a fibromatous stroma. The glands are lined by columnar or cuboidal epithelium with endocervical or endometrioid differentiation. The stroma shows no atypia or condensation around the glands, and the mitotic index is very low (<2 mitoses per 10 HPFs;39 Figure 13.14). The tumor does not invade into the cervical stroma.40 A confident diagnosis of adenofibroma requires the examination of the entire lesion to rule out the more common adenosarcoma; therefore, the diagnosis of adenofibroma cannot be made on curetted material or biopsy.41

Adenomyoma

This uncommon biphasic tumor is composed of benign glands admixed with a variable amount of smooth muscle and fibrous tissue. Patients range in age from 21 to 55 years (mean, 40 years) and, although usually asymptomatic, can present with vaginal bleeding or discharge. The tumors are well circumscribed, frequently polypoid, and range in size from 2.5 to 8.0 cm. Most are found in the upper cervical canal with a rare case arising in its lower end. The tumor glands are usually lined by endocervical epithelium. However, a few glands can be lined by endometrioid or tubal epithelium. The glands range from regular, small, round to oval to irregular and dilated with papillary infoldings. A vague lobular pattern is usually present. Atypia is not found in the epithelial or the stromal component. Less than 1 mitosis per 10 HPFs is seen in the epithelial component whereas the stromal component lacks mitotic activity. Cytoplasmic CEA immunoreaction can be focally detected in the glandular epithelium.42 The differential diagnosis includes: (1) minimal deviation adenocarcinoma, endocervical type (adenoma malignum), an ill-defined tumor that grossly expands the cervical wall and contains numerous glands, haphazardly distributed in the cervical stroma with at least focal desmoplasia, cytologic atypia, and lymphovascular invasion; (2) adenosarcoma, which shows minimal or no smooth muscle differentiation, intracystic or surface papillary stromal projections, and at least focal periglandular stromal condensation, stromal atypia, and 2 or more mitoses per 10 HPFs; or (3) endocervicosis, which lacks the smooth muscle stroma, lobular organization, and gross circumscription seen in adenomyoma.

Adenosarcoma

Pathology

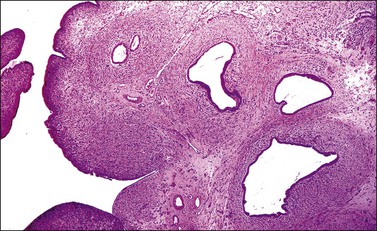

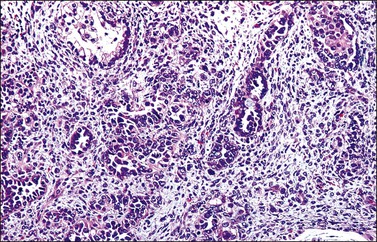

Cervical adenosarcomas range in size from 1.5 to 20 cm and usually have a polypoid configuration. Most are solitary but may be multiple.43,44 Characteristically, they show relatively bland, occasionally atypical, glands intermixed with a low-grade homologous sarcoma. A leaf-like pattern due to growth of the stromal component into dilated glands and/or the tumor surface is characteristic. Most cases show a distinctive band of hypercellular stroma surrounding the glandular epithelium (periglandular cuffing). It has been stated that the diagnosis of adenosarcoma requires one or more of the following findings: marked nuclear atypia of the stromal cells; 2 or more stromal mitoses per 10 HPFs; and stromal hypercellularity, usually forming periglandular cuffs.39 However, most cases display at least two of these features (Figures 13.15 and 13.16). Usually, the epithelial component is endocervical type with focal squamous metaplasia, although endometrioid or tubal-type epithelia may be seen. In nearly all cases, there is focal epithelial atypia. The glandular epithelial cells show irregularly shaped abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and enlarged nuclei. By definition, however, these features are insufficient to diagnose adenocarcinoma. Occasionally, the sarcomatous component shows heterologous elements in the form of skeletal muscle, cartilage, lipoblasts, or bone.43,44 A minority of cases show ‘sarcomatous overgrowth,’ defined as the presence of sarcoma occupying at least 25% of the tumor volume and frequently high grade.39 From a prognostic viewpoint, finding sarcomatous overgrowth is important since it indicates potential aggressive behavior.45 In fact, in our experience, foci of high-grade sarcoma even representing <25% of the tumor may also indicate an aggressive behavior.

Immunohistochemistry

Adenosarcomas with sarcomatous overgrowth often show strong immunoreaction for Ki-67 and p53 and loss of CD10 and progesterone receptor immunoexpression. Immunoreactivity for these markers is similar in classic adenosarcomas and adenofibromas.41

Differential Diagnosis

Adenofibromas are composed of benign epithelial and stromal components, and, particularly, lack hypercellularity, nuclear atypia, or mitotic activity in the stroma. As discussed in Chapter 20, many pathologists doubt adenofibromas even exist or can be diagnosed with certainty, since adenosarcomas may appear histologically so well differentiated, and yet may behave aggressively. We recommend a low threshold in the diagnosis of adenosarcomas when pathologic doubt exists or there is a clinical history of ‘recurrent polyps.’

Clinical Management and Prognosis

Cervical adenosarcomas are usually treated by hysterectomy. If less than hysterectomy is done in a young patient willing to preserve fertility, close and reliable follow-up is mandatory. Local resection of a polypoid adenosarcoma followed by recurrence in the corpus several years postoperatively has been fatal.41 Adjuvant radiotherapy may be considered in cases with invasion into the cervical wall. Cases with sarcomatous overgrowth should be treated like other high-grade sarcomas of the uterus.39

Carcinosarcoma (Malignant Mixed Müllerian Tumor)

Carcinosarcoma consists of admixed but distinct malignant epithelial and stromal elements (Figures 13.17 and 13.18). It is rarely found in the cervix.46 Most patients are elderly (mean age, 60 years), but the tumor may develop in children and the very old.46–48 HPV 16 has been identified in a few cases.46 The most common symptoms at presentation are vaginal bleeding or spotting, with an occasional asymptomatic case being detected by a cervical smear. Grossly, the tumor is generally polypoid and ranges in size from 1 to 10 cm. Microscopically, the epithelial component may be an endometrioid adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basaloid squamous carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, or adenoid basal carcinoma, while the mesenchymal component may be homologous (fibrosarcoma, endometrial stromal sarcoma, high-grade spindle cell sarcoma) or heterologous (rhabdomyosarcoma, chondrosarcoma). The differential diagnosis includes adenosarcoma, as discussed above, and sarcomatoid carcinoma. Most cases present with FIGO stage I disease.46–48 Although the experience with cervical carcinosarcomas is limited, prognosis seems to be better than that of similar tumors of the corpus.46,47

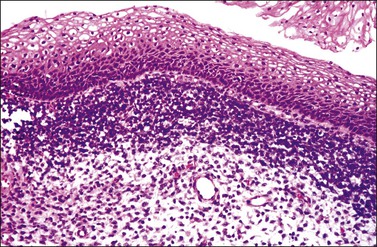

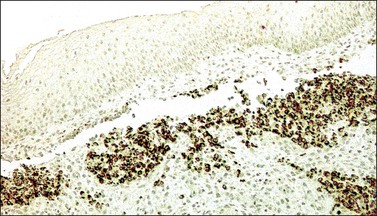

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma with classic botryoid features is the most common sarcoma of the uterine cervix.49 It mostly affects young women aged 12–26 years (average, 18 years).50 However, it is occasionally seen in older patients, up to 58 years of age.51 The most common symptom is vaginal bleeding. In some cases, a mass protrudes through the introitus or the tumor is detected during a routine gynecologic examination. Grossly, the tumors are polypoid and measure 2–10 cm in size.50 Microscopically, they show a ‘cambium layer,’ i.e., a subepithelial condensation of embryonal rhabdomyoblasts (Figure 13.19). The tumor cells vary in appearance, ranging from small cells to cells with definitive rhabdomyoblastic differentiation.50 The cells are usually reactive for desmin (Figure 13.20), myo-D1, and myogenin. However, nuclear staining for myo-D1 and myogenin may be absent or sparse in some embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas.52 The prognosis of cervical sarcoma botryoides is more favorable than that of other types of rhabdomyosarcoma. Surgery, including fertility-sparing procedures in selected cases, combined with chemotherapy is the treatment of choice.53

Smooth Muscle Tumors (Leiomyoma and Leiomyosarcoma)

Leiomyomas are uncommon in the uterine cervix.54 They are usually an incidental finding and may occur in all the variants that have been described in the uterine corpus. Cervical leiomyosarcomas are also uncommon. They occur in perimenopausal or postmenopausal women, with a rare case seen in a pediatric patient. These tumors are usually large.49 They can be spindle cell (conventional) type, epithelioid, or myxoid. The diagnostic criteria to distinguish these malignant tumors from their benign counterparts are those used for smooth muscle tumors of the corpus; thus, the diagnosis of conventional (spindle cell) leiomyosarcoma is based on the presence of two of the three following features: (1) diffuse severe nuclear atypia, (2) coagulative tumor cell necrosis, and (3) a mitotic index of ≥10 mitoses per 10 HPFs.55 In contrast, the diagnostic criteria for epithelioid leiomyosarcomas are not well established. These tumors usually show a combination of nuclear atypia (either grade 2 or 3) and a mitotic index of at least 4 mitoses per 10 HPFs.56 Myxoid leiomyosarcomas are frequently large tumors with infiltrative margins, mild to moderate nuclear atypia, and very few mitoses. Tumor necrosis may or may not be present.57,58 Since the experience with cervical leiomyosarcoma is limited, no specific therapy has been recommended.

Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor

This tumor, also known as ‘malignant schwannoma,’ ‘neurogenic sarcoma,’ or ‘neurofibrosarcoma,’ is composed of cells of the peripheral nerve sheath. Eight cases have been reported in the cervix. Patients ranged in age from 25 to 73 years (mean, 50 years) and had no history of neurofibromatosis. The tumors were polypoid, measured 3–4 cm, and were composed of atypical and mitotically active spindle cells arranged in a herringbone, nodular, or storiform patterns. Epithelioid as well as pigmented areas have been described. This tumor has a variable expression of S-100 and is negative for desmin, myoglobin, and actin. Three of the four cases with available follow-up of 1–2 years were free of disease, while one patient developed abdominal metastases less than 2 years after diagnosis.49

Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor/Ewing Sarcoma

This is a primitive round cell tumor showing varying degrees of neuroectodermal differentiation. Ten cases arising in the uterine cervix have been reported. Patients ranged in age from 21 to 51 years. Vaginal bleeding was the most common symptom. The tumor ranged from 5 to 7 cm. Most patients with localized disease at presentation were free of disease after an average follow-up of 19 months. Treatment included surgery with neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy.49

Alveolar Soft Part Sarcoma

This is a tumor of uncertain origin composed of uniform, large cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm arranged in alveolar and/or solid nests (Figure 13.21). The patients range in age from 8 to 39 years (mean, 29.9 years). Vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom, although some cases can be incidental findings. Grossly, the tumor is well circumscribed and ranges from 0.2 to 4 cm in size. Mitotic activity is usually low. A rare case has metastasized to a pelvic lymph node. Most patients have been treated with hysterectomy, with a few patients treated with radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Although experience with alveolar soft part sarcomas of the cervix is limited, they seem to have a better prognosis than their soft tissue counterparts. So far, no pulmonary or brain metastases or death has been reported.49

Blue Nevus

Cervical blue nevus of the common type is seen mostly in patients in their fifth or sixth decades of life as an incidental finding. Grossly, it consists of single or multiple, 0.1–0.4 mm, blue to gray macules located in the endocervix. Microscopically, it shows slender, wavy, and dendritic melanin-containing cells arranged in irregular clusters in the superficial cervical stroma (Figure 13.22). These cells are S-100 positive. A rare case of cellular blue nevus has been reported in the cervix.59

Malignant Melanoma

Malignant melanomas arising in the cervix are exceptionally rare.60 While the age range is wide (19–78 years), most women are postmenopausal.61 The most common symptom is vaginal bleeding. Occasional tumors are detected during routine clinical examination by cervical smear or the discovery of a distant metastasis.61,62

Pathology

The tumors are usually polypoid and red, brown, gray, black, or blue. Frequently, they are ulcerated. About 25% of cases are amelanotic. The neoplastic cells are usually epithelioid or spindle (Figure 13.23). Intranuclear inclusions and multinucleated tumor giant cells are common. Occasional variants include desmoplastic melanoma63 and a clear cell type with polygonal cells that contain glycogen and mimic those of clear cell carcinoma.64 Criteria that favor a primary cervical origin include the presence of a junctional component (Figure 13.24), melanosis in the squamous or glandular epithelium, and absence of a primary or regressed melanoma elsewhere, especially in the skin, uveal tract, and other mucosal sites.61

Immunohistochemistry

The tumor cells are always reactive for either S-100 protein or HMB45, or both.61,63,65

Clinical Behavior and Management

Most cases of cervical melanoma present with FIGO stage I or II tumors. Malignant melanomas are aggressive tumors. The 5 year survival rates for patients with stage I, II, and III/IV tumors are 25%, 14%, and 0%, respectively. The mean overall survival rate for all cervical melanomas is 2.4 years.61 There is no standard treatment for melanoma of the cervix. However, treatment with radical hysterectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, and partial vaginectomy with or without adjuvant radiation therapy has been recommended.66

Lymphoma and Leukemia

General Features

Most cases of lymphoma or leukemia involving the uterine cervix represent a manifestation of widespread disease. Occasionally, however, lymphomas arise in the cervix and most are diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The second most common type is follicular lymphoma.67–69 Much more rare are cases of mantle cell lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma of the nasal type, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma.68–72 Although occurring over a wide age range (20–80 years), cervical lymphomas are predominantly seen in premenopausal women (median age, 41 years). Bleeding is the most common symptom, although occasionally atypical lymphoid cells on a routine cervical smear have led to detection.70

Pathology: Macroscopic Features

The cervix is typically diffusely enlarged and barrel shaped70 (Figure 13.25), and often appears as a polyp or a tumor mass. Only rarely is the mucosa abnormal due to tumor ulceration. The tumor cut surface is usually fleshy, rubbery, or firm, and homogeneous or white to tan (Figure 13.26). Focal necrosis or hemorrhage may be seen. Granulocytic sarcomas may give a green color when freshly cut, thus the term ‘chloroma.’

Pathology: Microscopic Features

Most cases extend deep into the wall. In diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, neoplastic cells separate or surround endocervical glands without destroying the endocervical or squamous epithelium. Characteristically, a collagenous stroma separates the tumor from the ectocervical epithelium. The neoplastic cells are moderate to large, mostly rounded, with slightly pleomorphic nuclei, containing vesicular chromatin, small nucleoli, and numerous mitoses (Figures 13.27 and 13.28). Follicular lymphomas tend to infiltrate along the blood vessel walls at the periphery of the tumor.70

Pathology: Immunohistochemical Features

• A screening panel consisting of CD3, CD20, CD45, and keratin is useful to ascertain whether the tumor is a B-cell lymphoma (CD20+) (Figure 13.29), T-cell lymphoma (CD3+), granulocytic sarcoma (only CD45+), or carcinoma (keratin).

• In lymphomas composed of small cells, a panel consisting of CD5, CD10, cyclin D1, CD23, bcl-2, and bcl-6 helps to distinguish follicular lymphoma (CD10+, bcl-6+, bcl-2+) from follicular hyperplasia (bcl-2−), or chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CD5+, CD23−, cyclin D1+).

• For B-cell proliferations with large or intermediate cells or blasts, reactivity for CD10, CD79a, cyclin D1, bcl-6, Ki-67, T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (TdT), Epstein–Barr virus-latent membrane protein (EBV–LMP), and EBNA2 suggests precursor B-acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (CD79a+, CD10±, TdT±), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (CD10±, bcl-6±, Ki-67 reactivity in >90% of nuclei), blastic variant of mantle cell lymphoma (cyclin D1+), and Burkitt lymphoma (CD10+, TdT−, Ki-67 reactivity in >99% of nuclei).

• CD15 and CD30 are necessary to confirm the diagnosis of classic Hodgkin lymphoma and CD57 for the lymphocyte-predominant variant.

• The uncommon NK/T-cell neoplasms are better defined with antibodies to CD30 and ALK1 (anaplastic large cell lymphoma), CD1a and TdT, and TIA-1 and EBV antigens (cytotoxic T-cells and nasal-type NK cell tumors).

• To diagnose granulocytic sarcoma, testing with myeloperoxidase, CD4, CD68, and CD117 is required.70

Differential Diagnosis

Patients with a lymphoma-like lesion tend to be in the fourth decade of life, and experience bleeding and pelvic pain. Although a cervical mass is usually absent, erosion, erythema, bleeding at touch, nodularity, or a friable exophytic growth may be seen. Some patients have had the Epstein–Barr virus.73 Commonly, the infiltrate is superficial, rarely extending deeper than the endocervical glands. The infiltrate may be diffuse or nodular and contains a mixture of mature lymphocytes, polyclonal plasma cells, and polymorphonuclear cells with numerous mitoses. Immunohistochemically, B-cells predominate and the plasma cells exhibit polyclonality. Rare cases have monoclonal B-cells by polymerase chain reaction. A cervical cone may be necessary to rule out the presence of deep invasion.70

Primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) may cause diagnostic difficulties and attention to features such as the presence of fibrillary material and rosettes, as well as the use of immunomarkers such as synaptophysin, facilitate the diagnosis. CD99 is not specific for PNETs as it may often be detected in lymphoblastic lymphomas.70

Metastatic Tumors to the Cervix

Secondary involvement of the uterine cervix is commonly seen as a result of contiguous spread from carcinoma arising in the endometrium.74 Metastases to the uterine cervix are infrequent.75,76 In decreasing order of frequency, the primary sites of the metastatic tumors are ovaries, large bowel, stomach, breast, and kidneys. Occasionally, tumors arising in the lungs, pancreaticobiliary tract, and fallopian tubes, as well as appendiceal carcinoids, mesotheliomas, or melanomas may metastasize to the cervix.74,75 Metastases to the cervix are usually detected after the primary tumor has been diagnosed; however, they may be the initial presentation of the tumor. In certain cases, the disease is discovered after an abnormal Pap smear.74 Pathologic features that raise the possibility of metastatic tumor include extensive signet ring cells (Figure 13.30), a permeative growth pattern without destruction of the endocervical glands, multinodular growth, Indian file pattern, absence of an in situ component, predominant involvement of the outer cervical wall, numerous psammoma bodies, prominent lymphovascular involvement, extensive dirty necrosis, and a low mitotic activity in an invasive adenocarcinoma involving the cervix.74,77 Noticeably, some metastatic tumors may extend to the surface of the endocervical mucosa mimicking an in situ component. The use of immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization for high-risk HPV, and clinical correlation will allow a correct diagnosis.

Other Types of Cervical Neoplasms

Cases of neurilemmoma (schwannoma), neurofibromatosis, lipoma, liposarcoma, perivascular epithelioid cell tumor, angiosarcomas, undifferentiated sarcoma, and endometrial stromal sarcoma have been described in the uterine cervix.49,78–82

References

1. Brainard, JA, Hart, WR. Adenoid basal epitheliomas of the uterine cervix: a reevaluation of distinctive cervical basaloid lesions currently classified as adenoid basal carcinoma and adenoid basal hyperplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22:965–975.

2. Russell, MJ, Fadare, O. Adenoid basal lesions of the uterine cervix: evolving terminology and clinicopathological concepts. Diagn Pathol. 2006; 1:18.

3. Hart, WR. Symposium part II: special types of adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002; 21:327–346.

4. Ferry, JA, Scully, RE. ‘Adenoid cystic’ carcinoma and adenoid basal carcinoma of the uterine cervix. A study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988; 12:134–144.

5. Grayson, W, Taylor, LF, Cooper, K. Adenoid cystic and adenoid basal carcinoma of the uterine cervix: comparative morphologic, mucin, and immunohistochemical profile of two rare neoplasms of putative ‘reserve cell’ origin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999; 23:448–458.

6. Parwani, AV, Smith Sehdev, AE, Kurman, RJ, et al. Cervical adenoid basal tumors comprised of adenoid basal epithelioma associated with various types of invasive carcinoma: clinicopathologic features, human papillomavirus DNA detection, and P16 expression. Hum Pathol. 2005; 36:82–90.

7. Chen, TD, Chuang, HC, Lee, LY. Adenoid basal carcinoma of the uterine cervix: clinicopathologic features of 12 cases with reference to CD117 expression. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2012; 31:25–32.

8. Kwon, YS, Kim, YM, Choi, GW, et al. Pure basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2009; 24:542–545.

9. Banks, ER, Frierson, HF, Jr., Mills, SE, et al. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 40 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992; 16:939–946.

10. King, LA, Talledo, OE, Gallup, DG, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the cervix in women under age 40. Gynecol Oncol. 1989; 32:26–30.

11. Koyfman, SA, Abidi, A, Ravichandran, P, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2005; 99:477–480.

12. Grayson, W, Taylor, L, Cooper, K. Detection of integrated high risk human papillomavirus in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J Clin Pathol. 1996; 49:805–809.

13. Albores-Saavedra, J, Manivel, C, Mora, A, et al. The solid variant of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1992; 11:2–10.

14. McCusker, ME, Cote, TR, Clegg, LX, et al. Endocrine tumors of the uterine cervix: incidence, demographics, and survival with comparison to squamous cell carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2003; 88:333–339.

15. Albores-Saavedra, J, Gersell, D, Gilks, CB, et al. Terminology of endocrine tumors of the uterine cervix: results of a workshop sponsored by the College of American Pathologists and the National Cancer Institute. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997; 121:34–39.

16. Gilks, CB, Young, RH, Gersell, DJ, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine [corrected] carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997; 21:905–914.

17. Mannion, C, Park, WS, Man, YG, et al. Endocrine tumors of the cervix: morphologic assessment, expression of human papillomavirus, and evaluation for loss of heterozygosity on 1p,3p, 11q, and 17p. Cancer. 1998; 83:1391–1400.

18. Stoler, MH, Mills, SE, Gersell, DJ, et al. Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix. A human papillomavirus type 18-associated cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991; 15:28–32.

19. Abeler, VM, Holm, R, Nesland, JM, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the cervix. A clinicopathologic study of 26 patients. Cancer. 1994; 73:672–677.

20. Ambros, RA, Park, JS, Shah, KV, et al. Evaluation of histologic, morphometric, and immunohistochemical criteria in the differential diagnosis of small cell carcinomas of the cervix with particular reference to human papillomavirus types 16 and 18. Mod Pathol. 1991; 4:586–593.

21. Grayson, W, Rhemtula, HA, Taylor, LF, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus in large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a study of 12 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2002; 55:108–114.

22. Wistuba, II, Thomas, B, Behrens, C, et al. Molecular abnormalities associated with endocrine tumors of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1999; 72:3–9.

23. Moran, CA, Suster, S, Coppola, D, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the lung: a critical analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009; 131:206–221.

24. Viswanathan, AN, Deavers, MT, Jhingran, A, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: outcome and patterns of recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2004; 93:27–33.

25. Cohen, JG, Kapp, DS, Shin, JY, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the cervix: treatment and survival outcomes of 188 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 203(4):347e341–6.

26. Conner, MG, Richter, H, Moran, CA, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the cervix: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 23 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002; 6:345–348.

27. Gersell, DJ, Mazoujian, G, Mutch, DG, et al. Small-cell undifferentiated carcinoma of the cervix. A clinicopathologic, ultrastructural, and immunocytochemical study of 15 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988; 12:684–698.

28. Ishibashi-Ueda, H, Imakita, M, Yutani, C, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Mod Pathol. 1996; 9:397–400.

29. Seckl, MJ, Mulholland, PJ, Bishop, AE, et al. Hypoglycemia due to an insulin-secreting small-cell carcinoma of the cervix. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:733–736.

30. Straughn, JM, Jr., Richter, HE, Conner, MG, et al. Predictors of outcome in small cell carcinoma of the cervix. A case series. Gynecol Oncol. 2001; 83:216–220.

31. Zivanovic, O, Leitao, MM, Jr., Park, KJ, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: Analysis of outcome, recurrence pattern and the impact of platinum-based combination chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2009; 112:590–593.

32. McCluggage, WG, Kennedy, K, Busam, KJ. An immunohistochemical study of cervical neuroendocrine carcinomas: Neoplasms that are commonly TTF1 positive and which may express CK20 and P63. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010; 34:525–532.

33. Ohwada, M, Wada, T, Saga, Y, et al. C-kit overexpression in neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2006; 27:53–55.

34. Wang, HL, Lu, DW. Overexpression of c-kit protein is an infrequent event in small cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix. Mod Pathol. 2004; 17:732–738.

35. Serrano, MF, El-Mofty, SK, Gnepp, DR, et al. Utility of high molecular weight cytokeratins, but not p63, in the differential diagnosis of neuroendocrine and basaloid carcinomas of the head and neck. Hum Pathol. 2008; 39:591–598.

36. Embry, JR, Kelly, MG, Post, MD, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: prognostic factors and survival advantage with platinum chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2011; 120:444–448.

37. Sato, Y, Shimamoto, T, Amada, S, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathological study of six cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2003; 22:226–230.

38. Yun, K, Cho, NP, Glassford, GN. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a report of a case with coexisting cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and human papillomavirus 16. Pathology. 1999; 31:158–161.

39. Clement, PB, Scully, RE. Mullerian adenosarcoma of the uterus: a clinicopathologic analysis of 100 cases with a review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1990; 21:363–381.

40. Zaloudek, CJ, Norris, HJ. Adenofibroma and adenosarcoma of the uterus: a clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Cancer. 1981; 48:354–366.

41. Gallardo, A, Prat, J. Mullerian adenosarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 55 cases challenging the existence of adenofibroma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009; 33:278–288.

42. Gilks, CB, Young, RH, Clement, PB, et al. Adenomyomas of the uterine cervix of endocervical type: a report of ten cases of a benign cervical tumor that may be confused with adenoma malignum [corrected]. Mod Pathol. 1996; 9:220–224.

43. Jones, MW, Lefkowitz, M. Adenosarcoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathological study of 12 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1995; 14:223–229.

44. Kerner, H, Lichtig, C. Mullerian adenosarcoma presenting as cervical polyps: a report of seven cases and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 1993; 81:655–659.

45. Clement, PB. Mullerian adenosarcomas of the uterus with sarcomatous overgrowth. A clinicopathological analysis of 10 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989; 13:28–38.

46. Grayson, W, Taylor, LF, Cooper, K. Carcinosarcoma of the uterine cervix: a report of eight cases with immunohistochemical analysis and evaluation of human papillomavirus status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001; 25:338–347.

47. Clement, PB, Zubovits, JT, Young, RH, et al. Malignant mullerian mixed tumors of the uterine cervix: a report of nine cases of a neoplasm with morphology often different from its counterpart in the corpus. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1998; 17:211–222.

48. Sharma, NK, Sorosky, JI, Bender, D, et al. Malignant mixed mullerian tumor (MMMT) of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2005; 97:442–445.

49. Fadare, O. Uncommon sarcomas of the uterine cervix: a review of selected entities. Diagn Pathol. 2006; 1:30.

50. Daya, DA, Scully, RE. Sarcoma botryoides of the uterine cervix in young women: a clinicopathological study of 13 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 1988; 29:290–304.

51. Ferguson, SE, Gerald, W, Barakat, RR, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rhabdomyosarcoma of gynecologic origin in adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007; 31:382–389.

52. Riedlinger, WF, Kozakewich, HP, Vargas, SO. Myogenic markers in the evaluation of embryonal botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma of the female genital tract. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2005; 8:427–434.

53. Karaman, E, Akbayir, O, Kocaturk, Y, et al. Successful treatment of a very rare case: locally treated cervical rhabdomyosarcoma. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011; 284:1019–1022.

54. Tiltman, AJ. Leiomyomas of the uterine cervix: a study of frequency. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1998; 17:231–234.

55. Bell, SW, Kempson, RL, Hendrickson, MR. Problematic uterine smooth muscle neoplasms. A clinicopathologic study of 213 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994; 18:535–558.

56. Prayson, RA, Goldblum, JR, Hart, WR. Epithelioid smooth-muscle tumors of the uterus: a clinicopathologic study of 18 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997; 21:383–391.

57. Atkins, K, Bell, S, Kempson, R, Hendrickson, MR. Myxoid smooth muscle neoplasm of the uterus. Mod Pathol. 2001; 14:772.

58. Kindelberger, D, Hollowell, M, Otis, C, et al. Myxoid leiomyosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of ten cases. Mod Pathol. 2002; 20:203A.

59. Craddock, KJ, Bandarchi, B, Khalifa, MA. Blue nevi of the Mullerian tract: case series and review of the literature. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007; 11:284–289.

60. DeMatos, P, Tyler, D, Seigler, HF. Mucosal melanoma of the female genitalia: a clinicopathologic study of forty-three cases at Duke University Medical Center. Surgery. 1998; 124:38–48.

61. Clark, KC, Butz, WR, Hapke, MR. Primary malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: case report with world literature review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1999; 18:265–273.

62. Cantuaria, G, Angioli, R, Nahmias, J, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1999; 75:170–174.

63. Ishikura, H, Kojo, T, Ichimura, H, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: a rare primary malignancy in the uterus mimicking a sarcoma. Histopathology. 1998; 33:93–94.

64. Furuya, M, Shimizu, M, Nishihara, H, et al. Clear cell variant of malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2001; 80:409–412.

65. Kristiansen, SB, Anderson, R, Cohen, DM. Primary malignant melanoma of the cervix and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1992; 47:398–403.

66. Sugiyama, VE, Chan, JK, Kapp, DS. Management of melanomas of the female genital tract. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008; 20:565–569.

67. Au, WY, Chan, BC, Chung, LP, et al. Primary B-cell lymphoma and lymphoma-like lesions of the uterine cervix. Am J Hematol. 2003; 73:176–179.

68. Kosari, F, Daneshbod, Y, Parwaresch, R, et al. Lymphomas of the female genital tract: a study of 186 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:1512–1520.

69. Vang, R, Medeiros, JL, Ha, CS, Deavers, M. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving the uterus: a clinicopathologic analysis of 26 cases. Mod Pathol. 2000; 13:19–28.

70. Lagoo, AS, Robboy, SJ. Lymphoma of the female genital tract: current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006; 25:1–21.

71. Mhawech, P, Medeiros, LJ, Bueso-Ramos, C, et al. Natural killer-cell lymphoma involving the gynecologic tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000; 124:1510–1513.

72. Pomares Arias, E, Payeras Mas, M, Conchillo Armendariz, MA, et al. Linfoma difuso de células T de cervix uterino: una localización inusual de un tumor poco frecuente. An Med Interna. 2000; 17:432–433.

73. Hachisuga, T, Ookuma, Y, Fukuda, K, et al. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA from a lymphoma-like lesion of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1992; 46:69–73.

74. Clement, PB. Miscellaneous primary tumors and metastatic tumors of the uterine cervix. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990; 7:228–248.

75. Lemoine, NR, Hall, PA. Epithelial tumors metastatic to the uterine cervix. A study of 33 cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1986; 57:2002–2005.

76. Mazur, MT, Hsueh, S, Gersell, DJ. Metastases to the female genital tract. Analysis of 325 cases. Cancer. 1984; 53:1978–1984.

77. Malpica, A, Deavers, MT. Ovarian low-grade serous carcinoma involving the cervix mimicking a cervical primary. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2011; 30:613–619.

78. Boardman, CH, Webb, MJ, Jefferies, JA. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma of the ectocervix after therapy for breast cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000; 79:120–123.

79. Fadare, O, Parkash, V, Yilmaz, Y, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of the uterine cervix associated with intraabdominal ‘PEComatosis’: a clinicopathological study with comparative genomic hybridization analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2004; 2:35.

80. Folpe, AL, Mentzel, T, Lehr, HA, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:1558–1575.

81. LeMaire, WJ, Kreiss, C, Commodore, A, et al. Neurilemmoma: an unusual benign tumor of the cervix. Alaska Med. 2002; 44:63–65.

82. Morrel, B, Mulder, AF, Chadha, S, et al. Angiosarcoma of the uterus following radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1993; 49:193–197.