CHAPTER 307 Minimally Invasive Techniques for Lumbar Disorders

Minimally invasive techniques have evolved during the past decade to affect all aspects of lumbar spine surgery, from congenital disorders to adult deformity. Surgical series have demonstrated efficacy for decompressive procedures,1 short-segment lumbar fusions,2,3 and intradural exposures to spinal tumors4–7 and to tethered cords.8 More recent efforts have involved applying this experience to reduce the morbidity of deformity procedures. The advantages of minimally invasive spine surgery include decreased postoperative pain, more rapid postoperative mobilization, shorter length of hospitalization, shorter postoperative recovery times, and less disruption to the paraspinal muscles and ligaments that contribute to the maintenance of proper spine biomechanics.

Lumbar Diskectomy

Minimally invasive lumbar microdiskectomy, as it is known in the neurosurgical community, involves a similar procedure to traditional microdiskectomy but uses muscle dilators and a tubular retractor to access the interlaminar space with less soft tissue damage. It is performed routinely through tubes ranging from 14 to 22 mm in diameter and has been successfully applied to recurrent disk herniations9,10 and far lateral disk herniations,11,12 in addition to standard disk herniations. Originally developed using an endoscope for visualization, many practitioners use the operating microscope to perform the procedure through the same exposure, and excellent results have been reported.13 Whether a simple lumbar diskectomy using a tubular retractor has significant clinical advantage over an open diskectomy with a conventional subperiosteal muscle dissection and muscle retraction with a Taylor or Thompson-Farley retractor remains a matter of debate.14,15 However, when one considers the increased incisional length and muscle dissection required for proper exposure during a midline approach in heavy patients with typical disk herniations or in all patients with far lateral disk herniations, the advantages of using a tubular retractor centered directly over the site of pathology become obvious.

Stenosis Decompression

Although the advantages of minimally invasive techniques for microdiskectomy may be debatable, the advantages are clearer for patients with lumbar stenosis requiring a bilateral decompression. Through the same-sized incision as a microdiskectomy, a one-level or two-level stenosis decompression can be performed. Several variations of this procedure have been described, but all share the essential strategy of a bilateral decompression through a hemilaminar approach. This strategy has been proved feasible and effective in large clinical series.1,16

Lumbar Fusion

Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Interbody Fusion

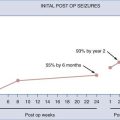

The indications for minimally invasive fusions are the same as for open fusions. The best studied of these techniques is the minimally invasive TLIF developed by Foley and Fessler.2,17,18 Its advantages include less blood loss, decreased perioperative narcotic requirements, and decreased length of stay compared with open lumbar fusions. Beyond a clear perioperative superiority, surgical results from open and minimally invasive fusions are similar in terms of validated self-reported patient outcomes after 1 year.3

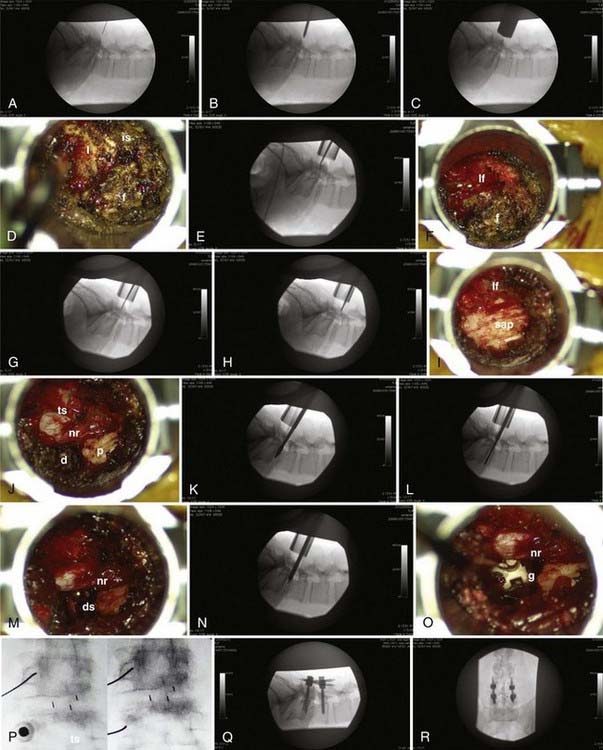

The procedure can be considered in two parts (Fig. 307-1): the interbody fusion and the percutaneous placement of pedicle screw fixation. An incision 2.5 to 3 cm long is made 3 to 5 cm off of midline. This distance is determined by the thickness of overlying soft tissues and can be measured on preoperative imaging to provide the desired working angle. A K wire is angled medially 35 to 45 degrees and docked on the facet joint. After muscle dilation, a working channel 22 to 26 mm is introduced directly over and perpendicular to the disk space, spanning the pedicles. After removal of residual soft tissue, the lamina, facet, and interlaminar space are identified. The canal is defined with curets, and a laminotomy is performed, exposing the ligamentum flavum. The inferior articular process is removed using an osteotome, drill, or rongeurs. All bone is saved for the interbody arthrodesis. The superior articular process is removed, as is the ligamentum flavum. The pedicle inferior to the disk space is identified, as are the exiting nerve root and disk anulus. The anulus is cleaned off of fat and epidural veins and incised. A series of pituitary rongeurs, curets, and scrapers are used to remove the intervertebral disk. An interbody graft is placed along with the arthrodesis material of the surgeon’s choice. Hemostasis is achieved, and the working channel is removed.

Transpsoas Lateral Interbody Fusion

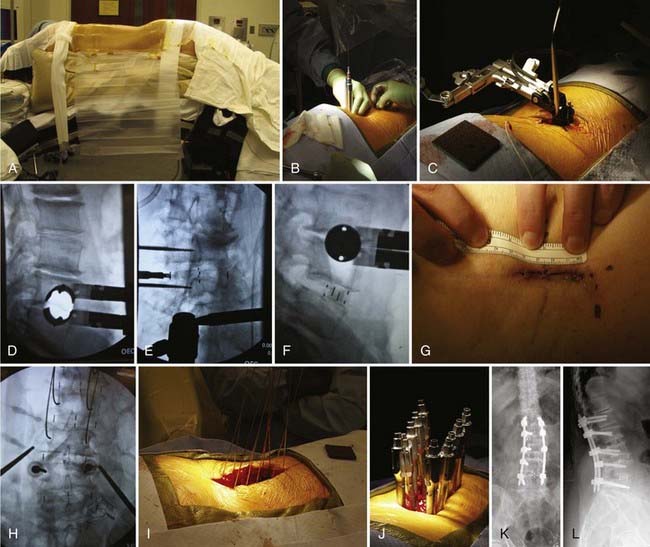

The transpsoas lateral interbody fusion can be summarized as follows (Fig. 307-2). The patient is placed in the lateral position on a standard operating table with the table break centered between the iliac crest and the bottom of the rib cage. The approach can be performed either from the left or from the right. In cases of scoliosis, graft placement is often facilitated by an approach from the convex side because it provides better access to the disk space. An axillary roll is placed to protect the dependent shoulder. The table is broken to maximize the working space between the rib cage and the iliac crest, and the patient is immobilized using a beanbag and cloth tape. A lateral fluoroscopic x-ray is taken, and the table is adjusted to ensure that the target disk space is perfectly in line with the fluoroscopic beam. The skin is then marked over a point that is in the center of the anterior third of the disk space. A 2- to 3-cm transverse incision is made, and after subcutaneous tissue dissection, the criss-crossing fibers of external and internal obliques are identified, split, and retracted using Army-Navy retractors. After this, the transversalis fascia is seen and sharply divided to expose the fat within the retroperitoneal space. A separate, more dorsal incision can be used to access the retroperitoneum at a point at which the peritoneal contents are more distant. In this instance, the surgeon enters the retroperitoneum through the second incision, develops a space under the true lateral incision, and then dissects down onto the surgeon’s finger.

Asgarzadie F, Khoo LT. Minimally invasive operative management for lumbar spinal stenosis: overview of early and long-term outcomes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38:387-399.

Chiou SM, Eggert HR, Laborde G, Seeger W. Microsurgical unilateral approaches for spinal tumour surgery: eight years’ experience in 256 primary operated patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1989;100:127-133.

Fessler RG. Minimally invasive percutaneous posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1512.

Foley KT, Holly LT, Schwender JD. Minimally invasive lumbar fusion. Spine. 2003;28:S26-S35.

Foley KT, Smith MM, Rampersaud YR. Microendoscopic approach to far-lateral lumbar disc herniation. Neurosurg Focus. 1999;7:e5.

German JW, Adamo MA, Hoppenot RG, et al. Perioperative results following lumbar discectomy: comparison of minimally invasive discectomy and standard microdiscectomy. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:E20.

Harrington JF, French P. Open versus minimally invasive lumbar microdiscectomy: comparison of operative times, length of hospital stay, narcotic use and complications. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2008;51:30-35.

Isaacs RE, Podichetty V, Fessler RG. Microendoscopic discectomy for recurrent disc herniations. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E11.

Isaacs RE, Podichetty VK, Santiago P, et al. Minimally invasive microendoscopy-assisted transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with instrumentation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:98-105.

Khoo LT, Fessler RG. Microendoscopic decompressive laminotomy for the treatment of lumbar stenosis. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:S146-S154.

Le H, Sandhu FA, Fessler RG. Clinical outcomes after minimal-access surgery for recurrent lumbar disc herniation. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E12.

Oktem IS, Akdemir H, Kurtsoy A, et al. Hemilaminectomy for the removal of the spinal lesions. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:92-96.

O’Toole JE, Eichholz KM, Fessler RG. Minimally invasive far lateral microendoscopic discectomy for extraforaminal disc herniation at the lumbosacral junction: cadaveric dissection and technical case report. Spine J. 2007;7:414-421.

Perez-Cruet MJ, Foley KT, Isaacs RE, et al. Microendoscopic lumbar discectomy: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:S129-S136.

Schwender JD, Holly LT, Rouben DP, Foley KT. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF): technical feasibility and initial results. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(suppl):S1-S6.

Tredway TL, Musleh W, Christie SD, et al. A novel minimally invasive technique for spinal cord untethering. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:ONS70-ONS74.

Tredway TL, Santiago P, Hrubes MR, et al. Minimally invasive resection of intradural-extramedullary spinal neoplasms. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:ONS52-ONS58.

Yasargil MG, Tranmer BI, Adamson TE, Roth P. Unilateral partial hemi-laminectomy for the removal of extra- and intramedullary tumours and AVMs. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 1991;18:113-132.

1 Khoo LT, Fessler RG. Microendoscopic decompressive laminotomy for the treatment of lumbar stenosis. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:S146-S154.

2 Isaacs RE, Podichetty VK, Santiago P, et al. Minimally invasive microendoscopy-assisted transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with instrumentation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:98-105.

3 Schwender JD, Holly LT, Rouben DP, Foley KT. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF): technical feasibility and initial results. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(suppl):S1-S6.

4 Chiou SM, Eggert HR, Laborde G, Seeger W. Microsurgical unilateral approaches for spinal tumour surgery: eight years’ experience in 256 primary operated patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1989;100:127-133.

5 Oktem IS, Akdemir H, Kurtsoy A, et al. Hemilaminectomy for the removal of the spinal lesions. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:92-96.

6 Tredway TL, Santiago P, Hrubes MR, et al. Minimally invasive resection of intradural-extramedullary spinal neoplasms. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:ONS52-ONS58.

7 Yasargil MG, Tranmer BI, Adamson TE, Roth P. Unilateral partial hemi-laminectomy for the removal of extra- and intramedullary tumours and AVMs. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 1991;18:113-132.

8 Tredway TL, Musleh W, Christie SD, et al. A novel minimally invasive technique for spinal cord untethering. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:ONS70-ONS74.

9 Isaacs RE, Podichetty V, Fessler RG. Microendoscopic discectomy for recurrent disc herniations. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E11.

10 Le H, Sandhu FA, Fessler RG. Clinical outcomes after minimal-access surgery for recurrent lumbar disc herniation. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E12.

11 Foley KT, Smith MM, Rampersaud YR. Microendoscopic approach to far-lateral lumbar disc herniation. Neurosurg Focus. 1999;7:e5.

12 O’Toole JE, Eichholz KM, Fessler RG. Minimally invasive far lateral microendoscopic discectomy for extraforaminal disc herniation at the lumbosacral junction: cadaveric dissection and technical case report. Spine J. 2007;7:414-421.

13 Perez-Cruet MJ, Foley KT, Isaacs RE, et al. Microendoscopic lumbar discectomy: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:S129-S136.

14 German JW, Adamo MA, Hoppenot RG, et al. Perioperative results following lumbar discectomy: comparison of minimally invasive discectomy and standard microdiscectomy. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:E20.

15 Harrington JF, French P. Open versus minimally invasive lumbar microdiscectomy: comparison of operative times, length of hospital stay, narcotic use and complications. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2008;51:30-35.

16 Asgarzadie F, Khoo LT. Minimally invasive operative management for lumbar spinal stenosis: overview of early and long-term outcomes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38:387-399.

17 Fessler RG. Minimally invasive percutaneous posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1512.

18 Foley KT, Holly LT, Schwender JD. Minimally invasive lumbar fusion. Spine. 2003;28:S26-S35.