Middle years

Chest pain

The first major concern for many in this age group is chest pain as it is a major factor affecting the health of those in the middle year’s group. With ischaemic heart disease developing during this age period, many are concerned that they will suffer angina or, worse, myocardial infarctions. Despite health education campaigns cardiac disease remains one of the biggest causes of debilitation in the UK and is the most common cause of premature death in people aged under 75 years in the UK. The British Heart Foundation estimates there are around 146 000 myocardial infarctions and 96 000 new cases of angina each year, and 2.5 million people in the UK have coronary heart disease (Allender et al. 2008, Garner 2012).

The overall cost of caring for angina has been calculated by Stewart et al. (2003) to be around 1 % of the NHS budget, mainly because of hospital bed occupancy and revascularization procedures; however, the burden of chest pain is far greater than the burden of angina. Nilsson et al. (2003) report that 1.5 % of primary care consultations are for chest pain, but only 17 % of these are associated with definite or possible angina. Despite this anyone who suffers a sudden onset of chest pain must be encouraged to seek immediate treatment (National Clinical Guideline Centre 2010). Time is heart muscle and to leave ischemic chest pain untreated for any period can result in catastrophic illness.

The patient presenting to the Emergency Department (ED) complaining of chest pain requires careful assessment to determine the symptoms and subtle features that differentiate chest pain which is cardiac in origin from that which is non-cardiac (Box 21.1). Chest pain can be very frightening for the patient, especially if it is the first episode, and staff need to assess and determine the likely signs of such pain (Gerber 2010). A number of key characteristics may help the assessing nurse to distinguish cardiac pain from that of other causes:

• location: the location of the pain can give a big clue to the nature of the cause. Cardiac pain is centrally located and chest pain that is peripheral to the sternum is rarely cardiac in nature

• radiation: cardiac pain brought on by ischaemia can often radiate to the jaw, neck and arms. Pain situated over the left anterior chest and radiating laterally may have various causes, such as pleurisy, chest wall injury and anxiety

• provocation: angina pain is precipitated by exertion, rather than occurring after it. It disappears a few minutes after the cessation of activity when blood flow can again match the oxygen requirements of the muscle. In contrast, pain associated with a specific movement, such as bending, stretching or turning, is likely to be musculoskeletal in origin

• character of the pain: ischaemic pain is often described as ‘dull’ or like a heavy object sitting on the chest. Chest pain caused by gastric problems can be described as a bloating or full feeling. Conversely pleural pain may be described as ‘sharp’ or ‘catching’ (Box 21.2)

• pattern of onset: the pain of aortic dissection, massive pulmonary embolism or pneumothorax is usually very sudden in onset (within seconds). Myocardial infarction may build up over several minutes or longer, whereas angina builds in proportion to the intensity of the exertion. Pain which develops over a longer period, such as days or even weeks, is often associated with respiratory illness or muscular damage

• associated features: the severe pain of a myocardial infarct, massive pulmonary embolus or aortic dissection is often accompanied by autonomic disturbance, including sweating, nausea and vomiting. If the patient is flushed, it may reflect a pyrexia or it may be stress-related. Pallor may be indicative of inadequate cardiac function or shock. Breathlessness is associated with raised pulmonary capillary pressure or pulmonary oedema in myocardial infarction and may accompany any of the respiratory causes of chest pain. Associated gastrointestinal symptoms may provide the clue to non-cardiac chest pain, such as heartburn, peptic ulceration, diarrhoea and vomiting.

On assessment, it is essential to perform a full set of observations. Temperature, if high, can indicate infection, the rate and depth of the pulse can indicate cardiac damage or arrhythmia, respiration rate can indicate respiratory distress and blood pressure can show cardiac instability. This in conjunction with an ECG can give the assessor a clearer picture as to the nature and cause of the chest pain.

The classic pain of angina pectoris is diffuse and retrosternal and will often diminish after rest. In the case of myocardial infarct, it is localized in the centre of the chest, is usually severe in nature, radiating to the left arm and jaw, and is not relieved by rest. Myocardial infarction and its management will be addressed in Chapter 27.

It is vitally important to take a calm, careful history from the patient who presents complaining of chest pain. While diagnosing angina is not as vital as that of a myocardial infarction, it is crucial to know if the patient is developing it as if not a cardiac event it is an indication that the patient is developing coronary heart disease (Harvey 2004).

The patient should firstly be asked to describe the pain – its intensity, location, duration, what brought it on and whether there is any relevant history (Jerlock et al. 2007). Assessing whether the patient can talk in sentences or whether there is pain on movement can indicate whether the chest pain is respiratory or musculoskeletal in origin. Note also that the fear and anxiety brought on by chest pain can exacerbate symptoms in the patient.

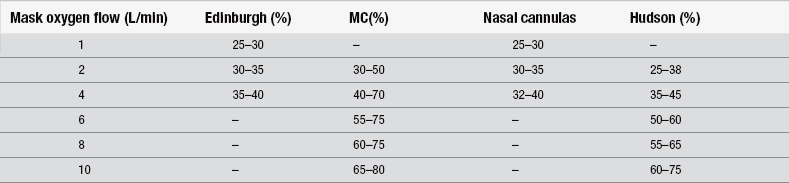

Recording of temperature, pulse and blood pressure and a 12-lead ECG can offer an indication of the likelihood of cardiac-related chest pain. A raised temperature may be a result of the breakdown of cardiac enzymes in response to a myocardial infarct that has happened within the previous few hours or may be a result of underlying infection. Recording of pulse oximetry, which measures arterial oxyhaemoglobin saturation (SpO2), gives important information about the supply of oxygen to the tissues. However, Nicholson (2004) suggests there is no definitive evidence that oxygen has any effect on cardiac ischaemia. Patients whose oxygen saturation levels are under 95 % on air are regarded as hypoxic and should be given high-flow oxygen via a mask (Table 21.1). Supplementary oxygen intake to increase oxygen saturation levels helps to relieve tachycardia induced by hypoxia, thereby reducing cardiac workload.

Table 21.1

Oxygen masks, flow rates and approximate concentrations of delivered oxygen

(After Jowett NI, Thompson D (1995) Comprehensive Coronary Care, 2nd edn. London: Scutari.)

In the absence of pain and with the patient at rest, the 12-lead ECG may be normal; therefore the ECG should also be performed during an episode of chest pain. ST-segment and T-wave changes, which occur during spontaneous chest pain and disappear with relief of the pain, are significant. Even without changes, the ECG should be repeated after one hour as the absence of abnormality does not rule out disease. Following myocardial infarction, the levels of some of the myocardial enzymes will rise, and estimation of their serum levels is often of diagnostic importance. In addition, the degree of their elevation may give some indication of the size of the infarct (Pride et al. 2009).

Jeremias & Gibson (2005) note that current guidelines for the diagnosis of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction are largely based on an elevated troponin level. While this rapid and sensitive blood test is certainly valuable in the appropriate setting, its widespread use in a variety of clinical scenarios may lead to the detection of troponin elevation in the absence of thrombotic acute coronary syndromes. Many diseases, such as sepsis, hypovolaemia, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, myocarditis, myocardial contusion and renal failure, can also be associated with an increase in troponin level. These elevations may arise from various causes other than thrombotic coronary artery occlusion. Given the lack of any supportive data at present, patients with non-thrombotic troponin elevation should not be treated with antithrombotic and antiplatelet agents. Rather, the underlying cause of the troponin elevation should be targeted. However, troponin elevation in the absence of thrombotic acute coronary syndromes still retains prognostic value. Thus, cardiac troponin elevations are common in numerous disease states and do not necessarily indicate the presence of a thrombotic acute coronary syndrome. While troponin is a sensitive biomarker to ‘rule out’ non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, it is less useful to ‘rule in’ this event because it may lack specificity for acute coronary syndromes (Jaffe et al. 2001).

The other measured cardiac enzymes are creatine kinase (CK), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT or AST) and they are released in the first 24 hours after the onset of a myocardial infarct. These enzymes may provide retrospective confirmation of infarction rather than a guide to immediate management (analgesia, aspirin, thrombolysis). If the clinical picture suggests myocardial infarction, the patient should be treated as such; however, these are predominantly undertaken as part of the inpatient workup rather than in the ED.

Pain relief may be achieved by administering sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) tablet or spray, repeated as necessary. Nitrates relax smooth muscle, mainly in the venous system, to increase capacitance and thus reduce cardiac preload. Arteriolar relaxation also occurs, with a fall in peripheral resistance (afterload). The resulting reduction in blood pressure leads to a reduction in chest pain. For patients suspected of having non-cardiac-related chest pain, magnesium trisilicate may relieve symptoms, suggesting an oesophageal or gastric origin of the pain. The use of antacids to differentiate epigastric pain from cardiac pain is common in emergency care; however, consideration must be given to the patient’s history, cardiac risk factors and ECG as well as the patient’s response to therapy (Novotny-Dinsdale & Andrews 1995). There must always be a high index of suspicion that any chest pain is cardiac in origin until clinical examination and tests prove otherwise (American College of Emergency Physicians 2000).

Abdominal pain

• age – some conditions are more likely to occur at different points on the age spectrum

^ was it a gradual onset or a sudden pain?

^ how does the patient describe the pain, is it stabbing, does it radiate through the back, is it burning?

^ location of the pain, does it move?

^ is there any vomiting, what did the vomit look like?

^ when does the pain come, e.g., only after eating, after exercise, at night?

• constipation or diarrhoea – if so, when was the last movement, what was the consistency?

• factors that exacerbate or improve symptoms, e.g., food, antacids, exertion

• medications, e.g., aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

• temperature – this can rule out infection or appendicitis

• social history – frequent alcohol use, especially binge drinking, can cause ulceration, gastritis, oesophageal varices or liver disease.

If there is any doubt in the assessing nurse’s mind then the patient should be regarded as potentially unwell and regular 15-minute observations commenced. Intravenous access should be established and a full examination of the abdomen undertaken (see Chapter 29).

Obesity

Obesity is now a major issue for the NHS from strategic management issues regarding equipment to the care and treatment of the patient presenting with obesity. It is estimated that current spending is around is ≤1bn per year and likely to get higher as in recent years it has become a major concern for the population of the UK (Shan 2008). While not an emergency condition, its presence can lead to attendance, from joint injury (see Chapter 6) to diabetes, from gastric pain to cardiac injury (Box 21.3).

It is now considered good practice to calculate the body mass index (BMI) on all patients (Box 21.4); this can give an indication of potential underlying developing chronic conditions and can also allow the practitioner an opportunity to make a health-promotional intervention. Obese patients also have significantly higher airway management complications during anaesthesia than those within normal weight ranges (Woodall et al. 2012).

It is necessary for the emergency nurse to understand the implications for discharge advice for the patient who is obese; mobility may be reduced or skin integrity compromised. Any patient who has a BMI >30 should have this noted in the patient discharge letter as the GP should follow up the patient before the issue becomes worse.

Epigastric pain

The term ‘peptic ulcer’ refers to an ulcer in the lower oesophagus, the stomach, the duodenum or the jejunum after surgical anastomosis to the stomach. It is a common condition and has its highest incidence in males aged 40–55 years, with perforation occurring in approximately 5–10% of affected individuals. While epigastric pain resolves with antacids and is self-limiting and short-lived, ulcers are repetitive and are worse after specific foods or drinks. Although peptic ulcer disease is commonly suspected in dyspeptic patients, it is found much less often than suspected when patients undergo endoscopic investigation (Vakil 2005, Aro et al. 2006).

Ulceration of the gastric mucosa leads to excoriation and mucous membrane sloughing. An imbalance between pepsin, hydrochloric acid secretion and bicarbonate causes gastric erosion. Bacterial invasion from Helicobacter pylori has been implicated as an important aetiological factor in peptic ulcer disease, accounting for 90 % of duodenal ulcers and 70 % of gastric ulcers (Lassen et al. 2004). H. pylori causes acute inflammation of the mucosa by causing degeneration, detachment and necrosis of the epithelial cells. Chronic ingestion of medications that irritate the gastric mucosa, such as aspirin or NSAIDs, can also lead to the development of ulcers (Butcher 2004). While duodenal and gastric ulcers are different conditions, they share common symptoms and will be considered together.

Peptic ulceration is an umbrella term used to describe areas in the gastrointestinal tract that have been exposed to, and damaged by, acid and pepsin-containing secretions. The most common sites for peptic ulcers are the stomach (gastric ulcers) and the duodenum (duodenal ulcers) (Elliot 2002). A peptic ulcer may progressively erode the submucosal, muscular and serous layers of the gastrointestinal wall. When perforation occurs, the contents of the stomach escape into the peritoneal cavity; this occurs more commonly in duodenal than in gastric ulcers. The most striking symptom is sudden, severe pain; its distribution follows the spread of gastric contents over the peritoneum. Initially, the pain may be referred to the upper abdomen, but it quickly becomes generalized; shoulder tip pain may occur as a result of irritation of the diaphragm. The pain is accompanied by shallow respirations due to epigastric pain and limitation of diaphragmatic movements. A rapid pulse and reduction in blood pressure indicate shock. Pyrexia may also be present as a result of peritonitis. Pallor, a cold clammy skin, nausea and vomiting may be also evident. The abdomen is held immobile and has ‘board-like’ rigidity.

Joint injury

For some who have had a history of undertaking sport and continue to do so at an aggressive level, there may be injury due to overuse. This is addressed in further detail in the skeletal injuries chapter (Chapter 6).

Depression and life-changing events

For the nurse assessing it is advisable to be aware of the patient with frequent attendance and to ask for a fuller social history. In acute presentations it is essential that a full psychiatric assessment is undertaken by a specialist in mental health as follow-up treatment may be needed. For the partners and relatives of those who have died suddenly, a referral to a chaplain or a bereavement service may help limit the ongoing development of depression and mental illness. These issues are addressed more fully in Chapters 14 and 15.

Homelessness

Homelessness is the term used to describe a range of situations associated with insecure and inadequate shelter, including rough sleepers, persons staying in homeless shelters and people with nowhere to go following release from institutions such as prisons, psychiatric institutions or from foster care (Wright & Tompkins 2006, Hamden et al. 2011, Cross et al. 2012). Few would need convincing that the extreme conditions of homelessness and sleeping rough are bound to affect health (Joseph Rowntree Foundation 2000, Morrison 2009). The homeless are disproportionately white, male and middle-aged, although there are increasing numbers of young men and women and black and Asian people (Homeless Link 2002, Pleace & Quilgars 1996). In a study of the records of 1873 homeless users of an ED compared with 28 420 housed people, a disturbing health profile emerged (North et al. 1996):

• homeless people’s accidents and injuries were four times more likely to be the result of an assault than those of housed people

• homeless people had twice the rate of infected wounds compared with housed people. These infections were twice as likely to be severe enough to warrant an admission to hospital for further treatment

• a substantial proportion (10 %) of homeless people attending EDs did so for mental health reasons. This was the second largest presenting category for homeless people to ED, but only ranked tenth for housed attenders

• homeless people were five times more likely to attend EDs due to deliberate self-harm than were housed people. Depression was very common among people of no fixed abode and hostel residents

• asthma was twice as common among homeless as among housed attenders

• epilepsy was four times as common among homeless as among housed users of the ED.

More recent research by Griffiths (2002) has identified that:

• 30–50% of homeless people experience mental health problems

• about 70% of homeless people misuse drugs

• about 50% of homeless people are dependent on alcohol

• rough sleepers are 35 times more likely to kill themselves than the general population.

The average age of death for homeless patients in the UK is between 40 and 44 (Office of the Chief Analyst 2010) and the literature on homelessness reveals the almost universal acceptance that there is a close link between ill health and homelessness (Morrison 2009, Hewett & Halligan 2010, Cross et al. 2012). Difficulties in obtaining access to primary healthcare services have meant that EDs have been an important source of healthcare provision for some homeless men and women. The Scottish Executive Health Department (2001) notes that while EDs are often the first point of contact for homeless people, staff may not have received training on homelessness issues and may not be in a position to respond appropriately to homelessness. Minor, acute illnesses pose particular problems for homeless people, who lack the facilities to look after themselves when well, and who are at risk of particular infections and infestations precisely because of their circumstances. Respiratory illness has been found to be a major health problem associated with being homeless. Other common conditions are chronic obstructive airways disease, tuberculosis, foot problems, infestations and epilepsy. Homeless people attending EDs also exhibit a disproportionate prevalence of infections, scabies and lice (Scott 1993).

One study found that homeless people attended ED six times as often as the housed population, are admitted four times as often and stay in hospital twice as long (Leicester Homeless Primary Heath Care Service 2008). Comparison of duration of stay in Hospital Episode Statistics data shows that the lengths of stay are generally appropriate for the admitting condition (Office of the Chief Analyst 2010). As Hewett & Halligan (2010) note, this means homeless people stay twice as long in hospital because they are twice as sick. Low temperature is an important cause of morbidity and mortality among the homeless. In Britain, for each degree Celsius that the winter is colder than average, there are an extra 8000 deaths (Balazs 1993), although a study by Brown et al. (2010) found no evidence that more homeless people would attend ED in colder weather.

Emergency nurses may offer the only social contact for some homeless people. A novel Canadian study found that compassionate care of homeless people who present to EDs significantly lowered their repeat visits. The researchers identified 133 consecutive homeless adults visiting one inner-city ED who were not acutely psychotic, extremely intoxicated, unable to speak English or medically unstable. Half were randomly assigned to receive compassionate care from trained volunteers. All patients otherwise had the usual care and were followed for repeat visits to EDs. The researchers found that the attendance by homeless people who received compassionate care was significantly lower. While acknowledging that compassionate care is not necessarily cost-effective if staff costs are taken into account, the authors argued that the basic justification for compassion is decency not economics (Redelmeier et al. 1995). At University College Hospital, London, people with an experience of homelessness join a GP and nurse team on regular ward rounds to visit homeless patients throughout the hospital, advocate for their treatment in hospital, plan for their discharge and support them in the community. Early indications are that this approach improves care and discharge planning, while offering overall savings by reducing the small numbers of patients with very prolonged durations of stay (Hewett 2010, Hewett & Halligan 2010).

Conclusion

The middle years is a pivotal timeframe when things can start to go wrong as the adult moves from being almost always healthy to almost always having a health concern. Through this continuum it is essential that the patient is fully assessed and treated with consideration. It may well be that there is nothing wrong and the concerns are psychological, but now is a good time to begin health promotion, ensuring the middle years adult remains healthy for as long as they can.

References

Adam, S.K., Osborne, S. Critical Care Nursing: Science & Practice. Oxford: Oxford Medical; 1997.

Allender, S., Peto, V., Scarborough, P., et al. Coronary Heart Disease Statistics. Oxford: British Heart Foundation and Stroke Association; 2008.

American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients Presenting with Suspected Acute Myocardial Infarction or Unstable Angina. Dallas: ACEP; 2000.

Aro, P., Storskrubb, T., Ronkainen, J., et al. Peptic ulcer disease in a general adult population. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;163(11):1025–1034.

Balazs, J. Health care for single homeless people. In: Fisher K., Collins J., eds. Homelessness, Health Care and Welfare Provision. London: Routledge, 1993.

Brown, A.J., Goodacre, S.W., Cross, S. Do emergency department attendances by homeless people increase during cold weather? Emergency Medicine Journal. 2010;27:526–529.

Butcher, D. Pharmacological techniques for managing acute pain in emergency departments. Emergency Nurse. 2004;12(1):26–36.

Cross, W., Hayter, M., Jackson, D., et al. Editorial: Meeting the health care needs associated with poverty, homelessness and social exclusion: the need for an interprofessional approach. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21(4):907–908.

Elliot, S. The treatment of peptic ulcers. Nursing Standard. 2002;16(22):37–42.

Garner, M. Chest Pain. In Wood I., Garner M., eds.: Initial Management of Acute Medical Patients: A Guide for Nurses and Healthcare Practitioners, second ed., London: John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

Gerber, T.C. Emergency department assessment of acute-onset chest pain: Contemporary approaches and their consequences. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2010;85(4):309–313.

Griffith, S. Assessing the Health Needs of Rough Sleepers. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister Homelessness Directorate; 2002.

Hamden, A., Newton, R., McCauley-Elsom, K., et al. Is deinstitutionalization working in our community? International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2011;20:274–283.

Harvey, S. The nursing assessment and management of patients with angina. British Journal of Nursing. 2004;13(10):598–601.

Hewett, N. Evaluation of the London Pathway for Homeless Patients. London: UCH; 2010.

Hewett, N., Halligan, A. Homelessness is a healthcare issue. Journal of The Royal Society of Medicine. 2010;103(8):306–307.

Homeless Link. An Overview of Homelessness in London. London: Homeless Link; 2002.

Jaffe, A.S., The World Health Organization, The European Society of Cardiology, The American College of Cardiology. New standard for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Cardiology in Review. 2001;9(6):318–322.

Jeremias, A., Gibson, C.M. Narrative review: Alternative causes for elevated cardiac troponin levels when acute coronary syndromes are excluded. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2005;142(9):786–791.

Jerlock, M., Welin, C., Rosengren, A., et al. Pain characteristics in patients with unexplained chest pain with ischaemic heart disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2007;6(2):130–136.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Research on Single Homelessness in Britain. London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2000.

Jowett, N.I., Thompson, D. Comprehensive Coronary Care, second ed. London: Scutari; 1995.

Lassen, A.T., Hallas, J., Schaffalitzky de Muckadell, O.B. Helicobacter pylori test and eradicate versus prompt endoscopy for management of dyspeptic patients: 6.7 year follow up of a randomised trial. Gut. 2004;53(12):1758–1763.

Leicester Homeless Primary Health Care Service, Annual Report 2007/2008. Leicester, Leicester Community Health Service, 2008.

Morrison, D.S. Homelessness as an independent risk factor for mortality: results from a retrospective cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38(3):877–883.

National Clinical Guideline Centre. Unstable Angina and NSTEMI: The Early Management of Unstable Angina and Non-ST-segment-elevation Myocardial Infarction. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2010.

Nicholson, C. A systematic review of the effectiveness of oxygen in reducing acute myocardial ischaemia. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2004;13:996–1007.

Nilsson, S., Scheike, M., Engblom, D., et al. Chest pain and ischaemic disease in primary care. British Journal of General Practice. 2003;53:378–382.

North, C., Moore, H., Owens, C. Go Home and Rest? The Use of an Accident and Emergency Department by Homeless People. London: Shelter; 1996.

Novotny-Dinsdale, V., Andrews, L.S. Gastrointestinal emergencies. In Thomas J., Proeh J.A., Kaiser, eds.: Emergency Nursing: A Physiologic and Clinical Perspective, second ed., Philadelphia: Saunders, 1995.

Office of the Chief Analyst. Healthcare for Single Homeless People. London: Department of Health; 2010.

Pleace, N., Quilgars, D. Health and Homelessness in London: A Review. London: King’s Fund; 1996.

Pride, Y.B., Applebaum, E., Lord, E.E., et al. Relation between myocardial infarct size and ventricular tachyarrhythmia among patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction following fibrinolytic therapy for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2009;104(4):475–479.

Redelmeier, D.A., Molin, J.P., Tibshini, R.J. A randomized trial of compassionate care for the homeless in an emergency department. The Lancet. 1995;345:1131–1134.

Scott, J. Homelessness and mental health. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;162:314–324.

Scottish Executive Health Department. Health and Homelessness Guidance. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Health Department; 2001.

Shan, Y. Tackling the obesity crisis in the UK. Primary Health Care. 2008;18(8):25–30.

Stewart, S., Murphy, N., Walker, A., et al. The current cost of angina pectoris to the National Health Service in the UK. Heart. 2003;89:848–853.

Vakil, N. Commentary: toward a simplified strategy for managing dyspepsia. Postgraduate Medicine. 2005;1176:13.

Woodall, N.M., Benger, J.R., Harper, J.S., et al. Airway management complications during anaesthesia, in intensive care units and in emergency departments in the UK. Trends in Anaesthesia and Critical Care. 2012;2(2):58–64.

Wright, N., Tompkins, C. How can health services effectively meet the health needs of homeless people? British Journal of General Practice. 2006;56:286–293.