Most common sites of metastases: Skin, lymph nodes (75%), lung (70%), liver (58%), CNS (54%), GI tract (40%)

• Lymph nodes

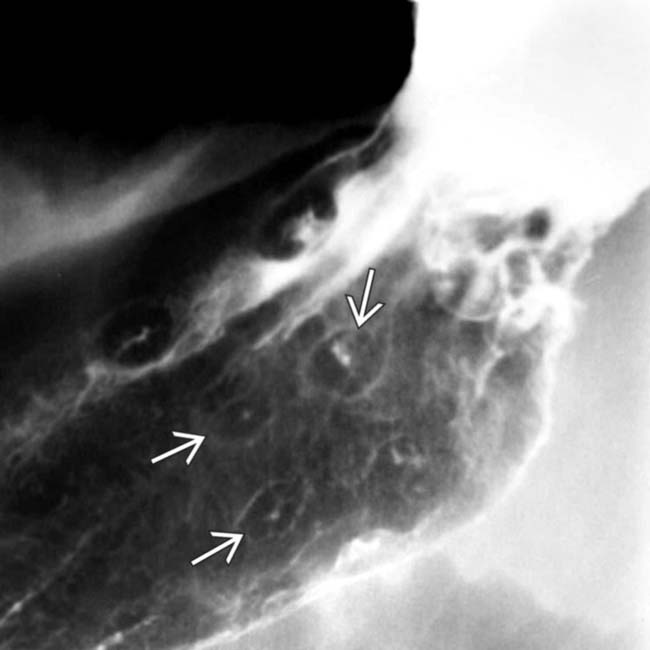

of 2 segments of colon, in keeping with bowel metastases.

of 2 segments of colon, in keeping with bowel metastases.

, with several others scattered throughout the small and large bowel (not shown). Lymphoma and GI stromal tumors can also cause similar aneurysmal dilatation.

, with several others scattered throughout the small and large bowel (not shown). Lymphoma and GI stromal tumors can also cause similar aneurysmal dilatation.

in the small bowel causing proximal bowel obstruction

in the small bowel causing proximal bowel obstruction  .

.

in the small bowel. Multifocal metastases to the bowel are not uncommon in melanoma.

in the small bowel. Multifocal metastases to the bowel are not uncommon in melanoma.IMAGING

General Features

CT Findings

• Lymph nodes

• Liver

• Mesenteric involvement

CLINICAL ISSUES

Presentation

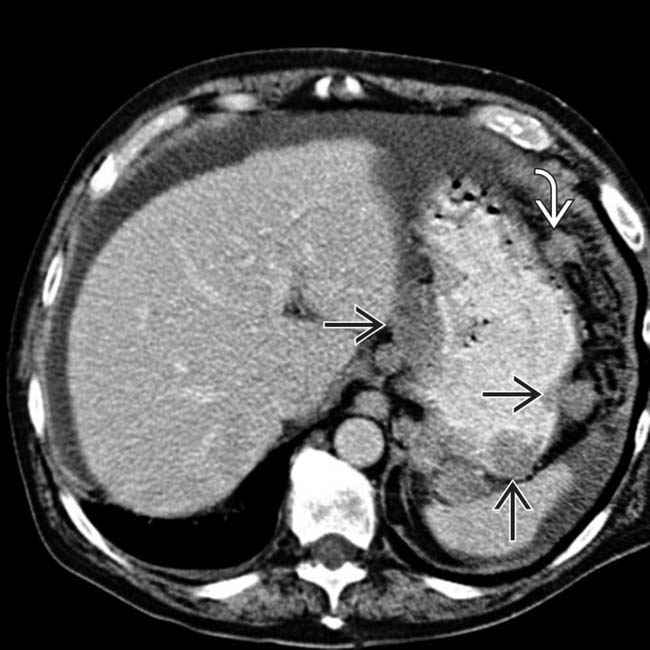

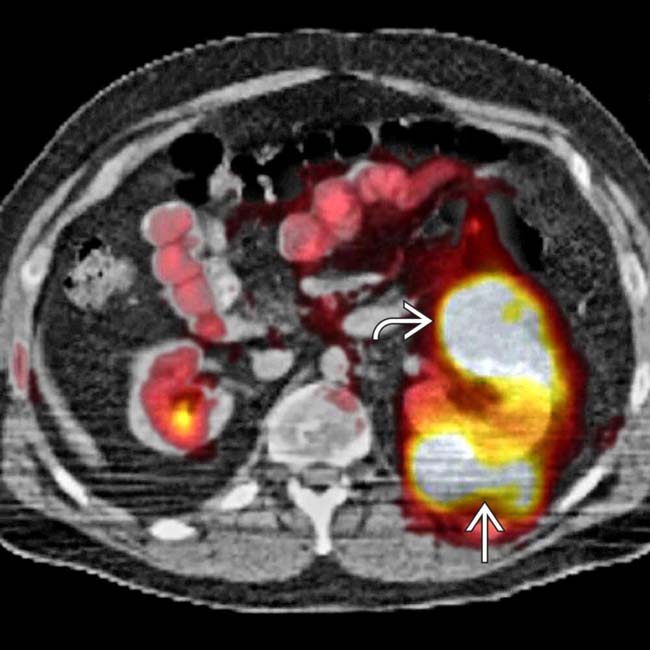

in the left adrenal gland in a patient with melanoma treated 10 years ago. Biopsy of the mass found this to be metastatic melanoma.

in the left adrenal gland in a patient with melanoma treated 10 years ago. Biopsy of the mass found this to be metastatic melanoma.

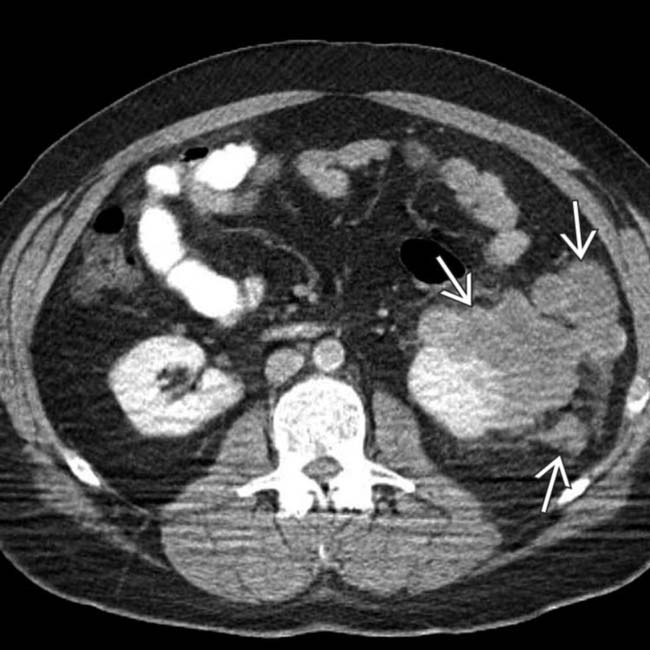

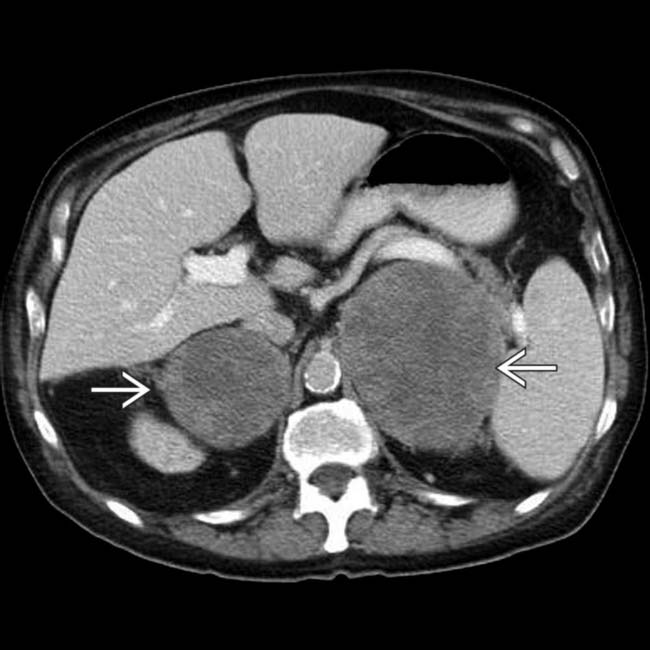

in a patient with melanoma. Metastases from melanoma have a unique predisposition for involving the perirenal space.

in a patient with melanoma. Metastases from melanoma have a unique predisposition for involving the perirenal space.

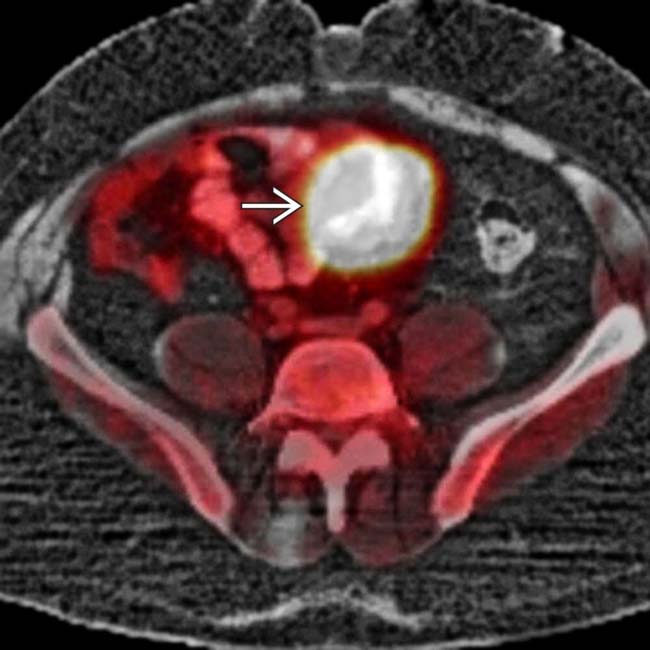

in the bladder. Notice the additional enhancing lesion

in the bladder. Notice the additional enhancing lesion  in the urethra. Both lesions were found to represent metastatic melanoma. The bladder lesion is indistinguishable from a primary bladder tumor without a clinical history.

in the urethra. Both lesions were found to represent metastatic melanoma. The bladder lesion is indistinguishable from a primary bladder tumor without a clinical history.

in the gallbladder. The patient had a history of melanoma and the lesion had been slowly growing over time. Melanoma is the most common cause of metastases to the gallbladder.

in the gallbladder. The patient had a history of melanoma and the lesion had been slowly growing over time. Melanoma is the most common cause of metastases to the gallbladder.

that have the peculiar feature of being hyperintense on T1WI, which is attributed to the melanin in these lesions. In some instances, metastases with fat or hemorrhage can also appear hyperintense on T1WI.

that have the peculiar feature of being hyperintense on T1WI, which is attributed to the melanin in these lesions. In some instances, metastases with fat or hemorrhage can also appear hyperintense on T1WI.

. Lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma can also result in bull’s-eye lesions.

. Lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma can also result in bull’s-eye lesions.

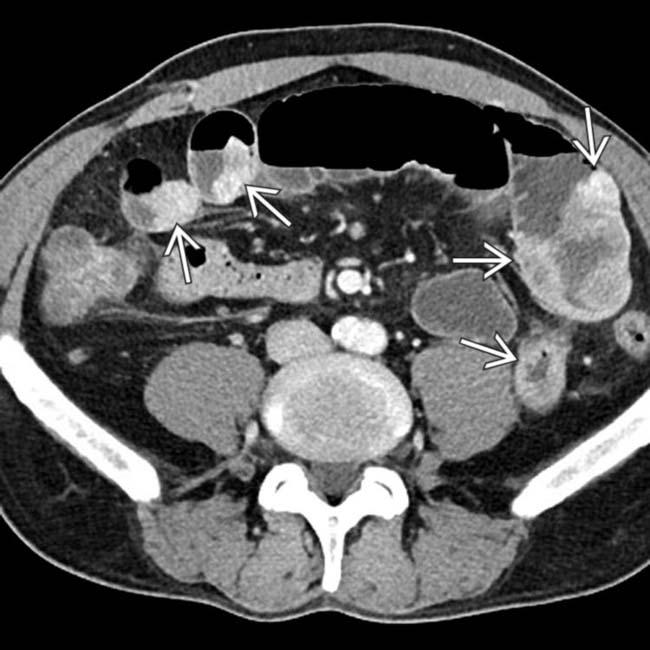

throughout the retroperitoneum, mesentery, and retrocrural spaces. There was also metastasis to the wall of the proximal small bowel (not shown).

throughout the retroperitoneum, mesentery, and retrocrural spaces. There was also metastasis to the wall of the proximal small bowel (not shown).

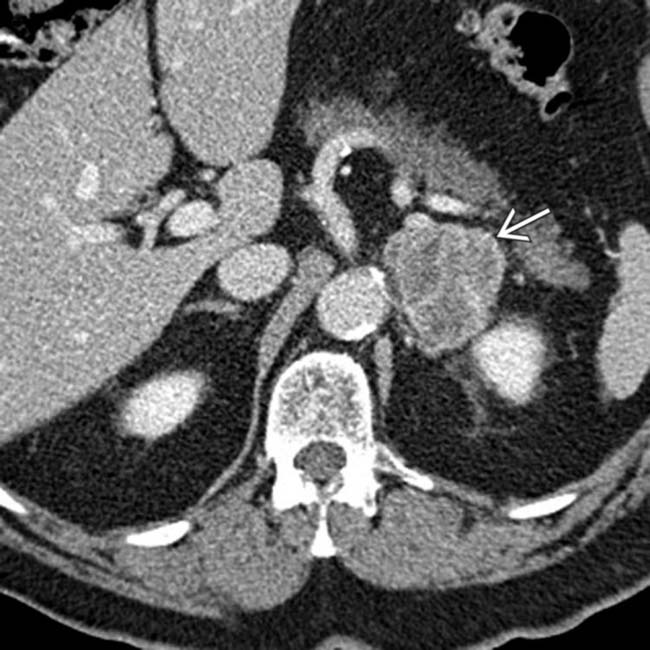

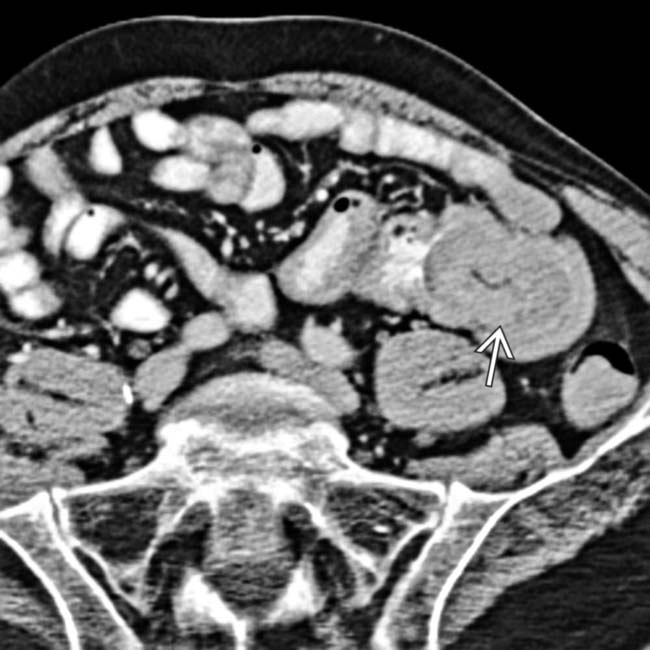

and a classic intussusception

and a classic intussusception  . The lead point of the intussusception is a metastasis in the wall of the intussusceptum.

. The lead point of the intussusception is a metastasis in the wall of the intussusceptum.

in the wall of the gallbladder. The gallbladder lesions progressed over time and represent metastases from the patient’s known melanoma.

in the wall of the gallbladder. The gallbladder lesions progressed over time and represent metastases from the patient’s known melanoma.

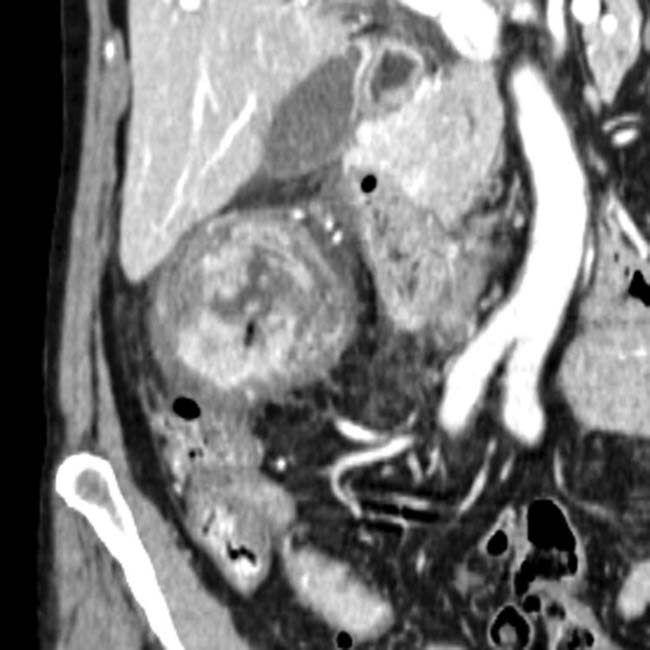

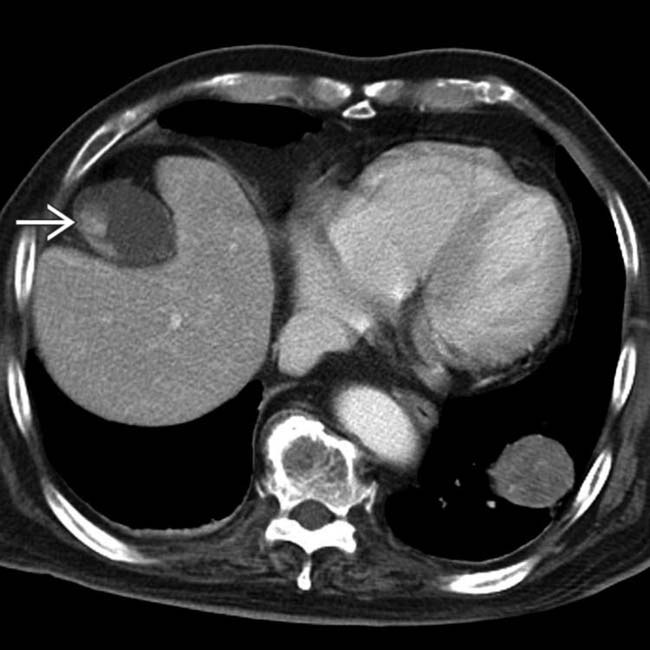

from melanoma. While the lesion is partially cystic, note that there is clearly a solid soft-tissue component differentiating this lesion from a cyst.

from melanoma. While the lesion is partially cystic, note that there is clearly a solid soft-tissue component differentiating this lesion from a cyst.

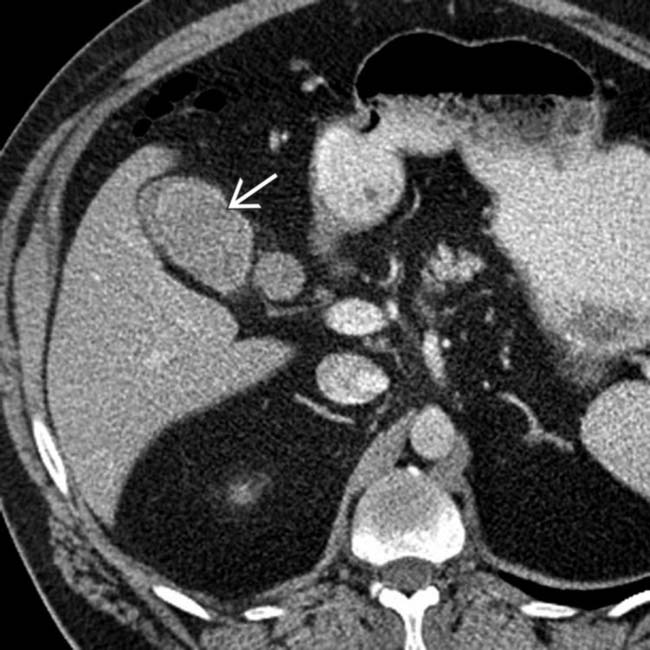

centered in the porta hepatis.

centered in the porta hepatis.

, which causes mild biliary dilatation

, which causes mild biliary dilatation  due to mass effect. The mass was biopsied and found to represent a large nodal metastasis from melanoma. The primary site of tumor was never found, something which occurs in roughly 3% of cases.

due to mass effect. The mass was biopsied and found to represent a large nodal metastasis from melanoma. The primary site of tumor was never found, something which occurs in roughly 3% of cases.

, and ascites from metastatic melanoma. There are multiple manifestations of widespread metastases from malignant melanoma.

, and ascites from metastatic melanoma. There are multiple manifestations of widespread metastases from malignant melanoma.

incidentally discovered in the proximal stomach. Note that the mass is subtly hypodense to the adjacent normal gastric wall.

incidentally discovered in the proximal stomach. Note that the mass is subtly hypodense to the adjacent normal gastric wall.

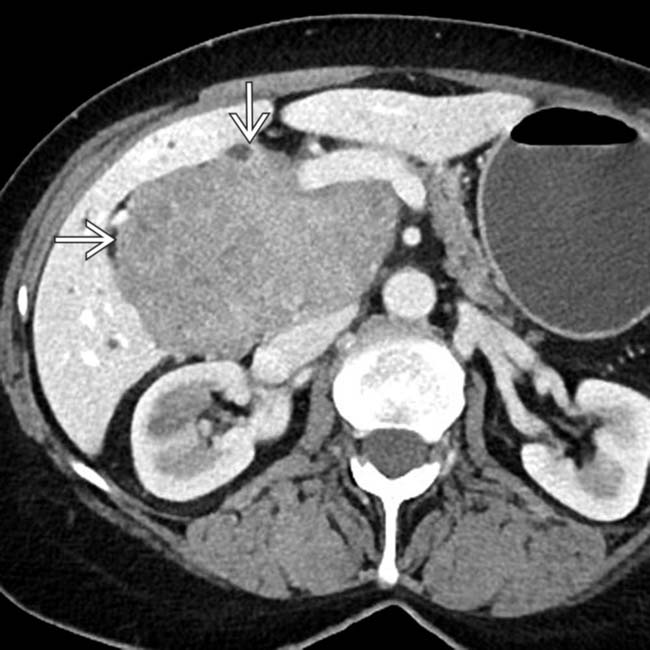

and others that are hyperdense

and others that are hyperdense  . The latter may be due to calcification, large amounts of melanin, or hemorrhage.

. The latter may be due to calcification, large amounts of melanin, or hemorrhage.

due to malignant melanoma metastases. These destroyed the adrenal parenchyma and resulted in adrenal insufficiency.

due to malignant melanoma metastases. These destroyed the adrenal parenchyma and resulted in adrenal insufficiency.

in the wall of the small intestine.

in the wall of the small intestine.

. Despite the large size of the metastasis, there was no bowel obstruction.

. Despite the large size of the metastasis, there was no bowel obstruction.

and peritoneum

and peritoneum  , resulting in ascites.

, resulting in ascites.

in a patient with a history of cutaneous melanoma.

in a patient with a history of cutaneous melanoma.

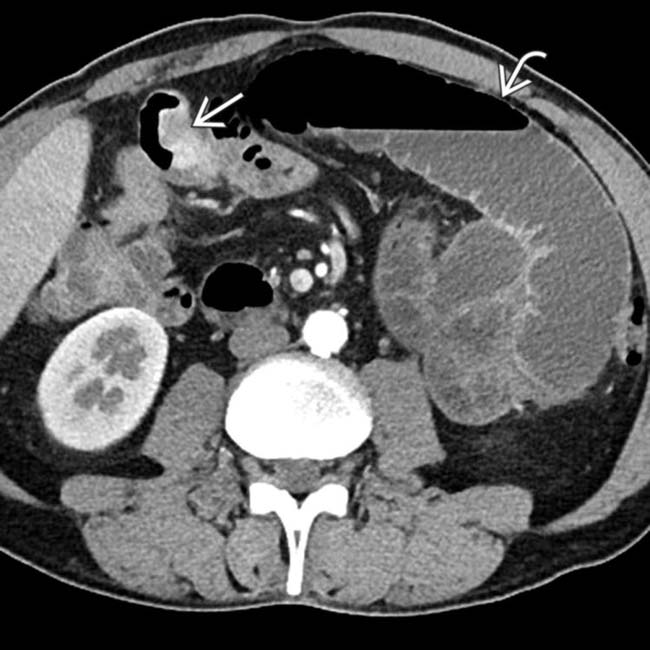

and perirenal space

and perirenal space  .

.

. Note the nodal and small-bowel metastases

. Note the nodal and small-bowel metastases  . The right ureter was obstructed due to a ureteral or retroperitoneal metastasis.

. The right ureter was obstructed due to a ureteral or retroperitoneal metastasis.

, abdominal wall

, abdominal wall  , lymph nodes, and perirenal space

, lymph nodes, and perirenal space  . “Unusual” sites of metastases are typical in patients with melanoma.

. “Unusual” sites of metastases are typical in patients with melanoma.