Chapter 35 Metastatic Brain Tumors

• A metastatic brain tumor means that the patient has stage IV cancer, with median survival of under 1 year.

• When a patient presents with a new brain metastasis, without a known primary site, the chance of finding the primary tumor during the patient’s lifetime is approximately 50%.

• As long as brain metastases undergo some form of treatment, the vast majority of patients will succumb to progression of systemic disease as opposed to brain metastases.

• Therapies for brain metastases are roughly equivalent, with local recurrence rate of 40% to 50% at 1 year. Therefore, the choice of therapy must be tailored to the individual patient, taking into account Karnofsky performance scale (KPS) score, medical comorbid conditions, systemic disease status, number of metastases, size and location of metastases, and symptoms.

• It is essential that treatment decisions for this lethal disease be made as a multidisciplinary team of oncologists, radiation oncologists, and neurosurgeons, as well as the patient and the patient’s family.

The histology and epidemiology of the primary cancer are the principal determinants of the frequency of cerebral metastases. Although the most common cancers diagnosed in adults in the United States are colorectal, prostate, breast, and lung, the two of these with the greatest proclivity to spread to the brain are lung and breast. In decreasing order of relative frequency, the majority of cerebral metastases are due to lung, breast, melanoma, renal, and colon cancers. Primary lung cancer accounts for 30% to 60% of all cerebral metastases. Lung cancer is more frequently diagnosed in males, and as a result, primary lung cancer is the most common cause of cerebral metastases in males. Brain metastases from lung cancer are often synchronous at diagnosis. Breast cancer accounts for 10% to 30% of all cerebral metastases and is the most common cause of cerebral metastases in females. Unlike brain metastases from lung cancer, breast metastases to the brain are more often metachronous. Melanoma accounts for 5% to 20% of all cerebral metastases, while renal and colon cancer each account for 5% to 10% of cerebral metastatic disease. The tendency of a primary cancer to metastasize to the brain has a distinct order of relative frequency. The frequency of cerebral metastases for melanoma is greater than 50%, but the low incidence of melanoma relative to other cancers accounts for its lower overall relative frequency of all cerebral metastases. Lung cancer has the second highest overall tendency to metastasize to the brain. The frequency of cerebral metastases for lung cancer is 20% to 60%, but there is variability in the frequency of cerebral metastases based on lung tumor type. Small cell lung cancer and lung adenocarcinoma tend to metastasize to the brain more frequently than other types of lung cancer. Breast cancer has the third highest overall tendency to metastasize to the brain, with a frequency of 20% to 30%.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Studies

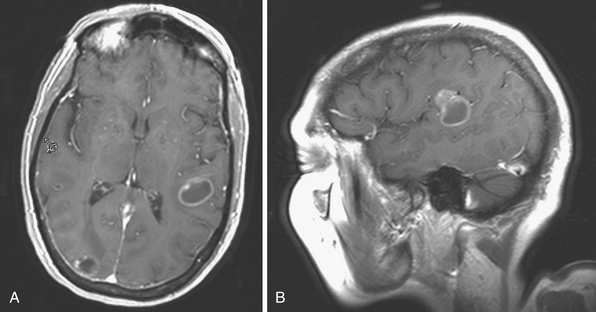

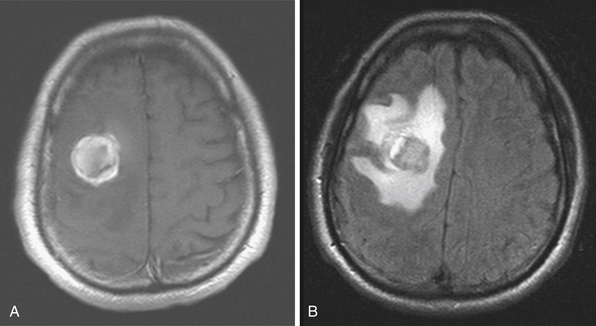

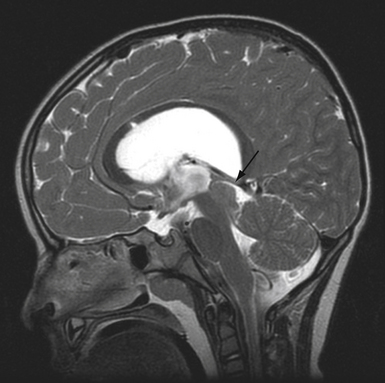

The best imaging tool for cerebral metastases is contrast-enhanced MRI (Figs. 35.1 and 35.2). On nonenhanced T1-weighted sequences, cerebral metastases generally appear isointense or hypointense. Certain metastases with intrinsically short T1, such as melanoma (due to the ferromagnetic melanin within the tumor), can appear hyperintense. Hemorrhage within the tumor will appear disorganized, with atypical evolution, and is best evaluated on T2-weighted gradient echo (GRE) sequences. On nonenhanced T2-weighted sequences, cerebral metastases generally appear hyperintense, but can be variable. Similarly, on FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) sequences the appearance of cerebral metastases can be variable, but is generally hyperintense. Both FLAIR and T2-weighted images usually demonstrate marked vasogenic edema. Tumor cysts and surrounding edema appear markedly hyperintense. The vast majority of cerebral metastases will enhance. On contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequences cerebral metastases show strong enhancement in variable patterns. Cerebral metastases usually do not show restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences and exhibit elevated apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values. The differential diagnosis of cerebral lesions with imaging characteristics similar to cerebral metastases includes abscess, encephalitis, malignant glioma, radiation necrosis, thromboembolic stroke, demyelinating disease, and resolving hematoma. Multiplicity of lesions or location in the posterior fossa may increase the likelihood that the lesions are metastatic, rather than primary.

Treatment Options and Outcomes

In general, cerebral metastases from systemic cancer are a harbinger of active systemic disease. With treatment, approximately 90% of patients with known brain metastases will succumb to systemic disease progression, rather than cerebral progression. Cerebral metastatic disease is complex and there is no one optimal treatment algorithm. If neurological deficits are present at the time of diagnosis of cerebral metastases, the median survival in untreated patients is 4 to 6 weeks. There are several patient factors associated with improved survival regardless of treatment. Karnofsky performance scale (KPS) score greater than 70, age less than 60 years, isolated cerebral metastases, a single cerebral metastasis, absent or controlled primary disease, and longer than 1 year since diagnosis of primary disease predict a better prognosis. Even with comprehensive treatment, median survival is only approximately 6 to 8 months. Initial treatment of symptomatic cerebral metastases includes high-dose corticosteroid therapy to decrease the edema that commonly occurs. Because most cerebral metastases are accompanied by a considerable amount of reactive, vasogenic edema, steroid therapy can often improve neurological function. The use of corticosteroids alone doubles median survival to 8 to 12 weeks. In patients who present with seizure, an antiepileptic should be initiated. There is controversy, though, regarding routine seizure prophylaxis. Medical therapy can manage the symptoms of cerebral metastases, but the primary treatment options for definitive management include whole-brain radiation therapy, surgical resection, and stereotactic radiosurgery.

Whole-Brain Radiation Therapy

Since the 1950s, whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) has been used to treat cerebral metastases. Several studies have examined the role of WBRT in treating cerebral metastases. Studies by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) established a median survival time of 4 to 6 months in cerebral metastases treated with WBRT. Additional studies demonstrated symptom improvement after WBRT. Cranial nerve deficits, symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure, headaches, and seizures have been shown to improve in 50% of patients after WBRT. Two separate studies from the RTOG identified favorable prognostic factors in patients with cerebral metastases treated with WBRT. Diener-West and colleagues used multivariate analysis and found a KPS score greater than 70, patient age less than 60 years, isolated cerebral metastases, and absent or controlled primary disease predictive of better survival.1 Gaspar and colleagues used recursive partitioning analysis and identified the same patient-related factors to predict improved survival following WBRT.2 The optimal WBRT dose-fractionation schedule was also assessed by the RTOG. Patients receiving higher-dose schedules of 20 to 40 Gy over a period of 1 to 4 weeks demonstrated greater duration of symptom improvement, shorter time of progression to improved neurological status, and greater rate of resolution of neurological symptoms compared to patients receiving ultrarapid schedules of 10 or 12 Gy in one or two fractions, respectively.3 The common treatment schedule for WBRT is 30 Gy in 10 fractions.

WBRT to control micrometastases is typically recommended following surgical resection of cerebral metastases. In a study by Patchell and colleagues, WBRT following surgical resection of a single cerebral metastasis was shown to decrease the frequency of and time to recurrence of cerebral metastases, but did not influence the length of survival.4 The common treatment schedule following surgery is 45 to 50 Gy plus a boost of 5 to 10 Gy for a total treatment dose of 55 Gy divided in low fractions of 1.8 to 2.0 Gy. The smaller daily fractions are recommended to reduce neurotoxicity. In patients who are not expected to live long enough to experience long-term radiation effects, higher daily fractions can be given. In the treatment of multiple cerebral metastases, a recent study by Kocher and colleagues assessed outcomes in patients with one to three cerebral metastases treated with surgical resection or stereotactic radiosurgery alone with or without adjuvant WBRT.5 The addition of adjuvant WBRT in the treatment of multiple cerebral metastases reduced intracranial relapse and death due to a neurological cause, but did not improve functional independence or overall survival. Prophylactic WBRT is not commonly used in the treatment of most systemic cancers. It is reserved for patients with small cell lung cancer who are in complete remission after treatment. Studies of prophylactic WBRT for small cell lung cancer have demonstrated a 5% improvement in survival at 3 years and a 25% reduction in the incidence of cerebral metastases.

Surgical Resection

Surgical resection is often considered the optimal treatment for symptomatic cerebral metastases. However, with surgery alone, there is approximately a 50% local recurrence rate at 1 year following a gross total resection. Patient selection is based on several factors, including the number, size, location, and histological type of cerebral metastases, as well as the patient’s clinical condition. The number of cerebral metastases present is a principal factor in the decision to treat with surgical resection. Conventionally, surgery has been reserved for patients with a single symptomatic cerebral metastasis in a surgically accessible location and an unknown primary diagnosis or primary disease known to be relatively radioresistant. Studies conducted in the 1990s demonstrated a benefit of surgical resection followed by WBRT for single cerebral metastasis compared with WBRT alone in patients with good neurological function. One of the decisive works in demonstrating improved survival after surgical resection was published by Patchell and colleagues. In this prospective randomized trial comparing surgical resection followed by radiation with WBRT alone in patients with a single cerebral metastasis, a KPS score greater than 70, and limited systemic disease, patients in the surgery and radiation group had longer survival, improved progression-free survival, and improved quality of life.6 The benefit of surgery has not been shown in patients with poor functioning or extensive systemic disease. The role of surgical resection in patients with multiple metastases is unclear. For patients with multiple cerebral metastases, the classic surgical treatment strategy is for resection of only large lesions with symptomatic mass effect. There have been no prospective randomized studies, but there is evidence showing that patients with multiple or recurrent cerebral metastases may also benefit from surgical resection. A retrospective review was performed to assess survival, comparing patients with resection of all cerebral metastases to patients with resection of only one of multiple cerebral metastases, with a control group of patients with resection of a single cerebral metastasis. The result showed that resection of all of multiple cerebral metastases is as effective as resection of single cerebral metastases in prolonging survival, provided that all cerebral metastases are resected.

The histological appearance of the primary disease is a significant factor in considering surgical resection for cerebral metastases. Lymphoma, small cell lung cancer, and germ cell tumors are sensitive to radiation and chemotherapy, and optimal treatment usually consists of fractionated radiation and chemotherapy. Melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and sarcomas are generally resistant to radiation, and surgical resection is the preferred treatment for cerebral metastases. Breast and non–small cell lung cancer are moderately sensitive to radiation, and surgery is often a component of multimodality treatment.

Stereotactic Radiosurgery

Radiosurgery in combination with WBRT for treatment of single cerebral metastases may provide a survival benefit and result in treatment outcomes that are similar to surgical resection followed by WBRT. Andrews and colleagues demonstrated improved survival in patients with a single unresectable cerebral metastasis treated with WBRT and radiosurgery boost compared to WBRT alone.7 In patients with multiple cerebral metastases, a randomized trial (Aoyama and colleagues) showed improved neurological function and local control in patients treated with radiosurgery and WBRT compared to WBRT alone, but there was no evidence for improved survival.8 Stereotactic radiosurgery can also be utilized to treat recurrent cerebral metastases or persistent cerebral metastases following WBRT.

Gaspar L.E., Mehta M.P., Patchell R.A., et al. The role of whole brain radiation therapy in the management of newly diagnosed brain metastases: a systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Neurooncol. 2010;96:17-32.

Kalkanis S.N., Kondziolka D., Gaspar L.E., et al. The role of surgical resection in the management of newly diagnosed brain metastases: a systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Neurooncol. 2010;96:33-43.

Linskey M.E., Andrews D.W., Asher A.L., et al. The role of stereotactic radiosurgery in the management of patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases: a systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Neurooncol. 2010;96:45-68.

Sperduto P.W., Chao S.T., Sneed P.K., et al. Diagnosis-specific prognostic factors, indexes, and treatment outcomes for patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases: a multi-institutional analysis of 4,259 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:655-661.

Videtic G.M.M., Gaspar L.E., Aref A.M., et al. American College of Radiology appropriateness criteria on multiple brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;77:961-965.

Please go to expertconsult.com to view the complete list of references.

1. Diener-West M., Dobbins T.W., Phillips T.L., et al. Identification of an optimal subgroup for treatment evaluation of patients with brain metastases using RTOG study 7916. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16:669-673.

2. Gaspar L., Scott C., Rotman M., et al. Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) brain metastases trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:745-751.

3. Borgelt B., Gelber R., Larson M., et al. Ultra-rapid high dose irradiation schedules for the palliation of brain metastases: final results of the first two studies by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7:1633-1638.

4. Patchell R.A., Tibbs P.A., Regine W.F., et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1485-1489.

5. Kocher M., Soffietti R., Abacuiglu U., et al. Adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation after radiosurgery or surgical resection of one to three cerebral metastases: results of the EORTC 22952-26001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:134-141.

6. Patchell R.A., Tibbs P.A., Walsh J.W., et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:494-500.

7. Andrews D.W., Scott C.B., Sperduto P.W., et al. Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: phase III results of the RTOG 9508 randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1665-1672.

8. Aoyama H., Shirato H., Tago M., et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery plus whole-brain radiation therapy vs. stereotactic radiosurgery alone for treatment of brain metastases: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2483-2491.