Chapter 100 Metabolic Disturbances

Hyperthermia in the Newborn

A more severe form of neonatal hyperthermia occurs in both newborn and older infants when they are warmly dressed. The diminished sweating capacity of newborn infants is a contributing factor. Warmly dressed infants left near stoves or radiators, traveling in well-heated automobiles, or left with bright sunlight shining directly on them through the windows of a closed room or automobile are likely to be victims. Body temperature may become as high as 41-44°C (106-111°F). The skin is hot and dry, and initially the infant usually appears flushed and apathetic. The extremities are warm. Tachypnea and irritability may be noted. This stage may be followed by stupor, grayish pallor, coma, and convulsions. Hypernatremia may contribute to the convulsions. Mortality and morbidity (brain damage) rates are high. Hyperthermia has been associated with sudden infant death, hemorrhagic shock, and encephalopathy syndrome (Chapter 64). The condition is prevented by dressing infants in clothing suitable for the temperature of the immediate environment. In newborn infants, exposure of the body to usual room temperature or immersion in tepid water usually suffices to bring the temperature back to normal levels. Older infants may require cooling for a longer time by repeated immersion. Attention to possible fluid and electrolyte disturbance is essential.

Neonatal Cold Injury

Neonatal cold injury usually occurs in abandoned infants, infants in inadequately heated homes during cold spells when the outside temperature is in the freezing range, and in preterm infants (Chapter 69). The initial features are apathy, refusal of food, oliguria, and coldness to touch. The body temperature is usually between 29.5 and 35°C (85-95°F), and immobility, edema, and redness of the extremities, especially the hands and feet, and of the face are observed. Bradycardia and apnea may also occur. The facial erythema frequently gives a false impression of health and delays recognition that the infant is ill. Local hardening over areas of edema may lead to confusion with scleredema. Hypoglycemia and acidosis are common. Hemorrhagic manifestations are frequent; massive pulmonary hemorrhage is a common finding at autopsy. Hypothermia in preterm infants can be prevented with special plastic wraps that reduce evaporation and heat loss. Because of their high ratio of surface area to body mass, preterm infants are very vulnerable to evaporation heat loss. Infants at <28-30 wk should be placed inside a clear polyethylene bag without prior drying. Neonatal cold injury in preterm infants occurs in the developing world and can be prevented with skin-to-skin (kangaroo mother) care. Treatment consists of warming and paying scrupulous attention to recognition and correction of hypotension and metabolic imbalances, particularly hypoglycemia. Prevention consists of providing adequate environmental heat. The mortality rate is about 10%; about 10% of survivors have evidence of brain damage.

Edema

Generalized edema occurs in association with hydrops fetalis (Chapter 97.2) and in the offspring of diabetic mothers. In premature infants, edema is often a consequence of a decreased ability to excrete water or sodium, although some have considerable edema without identifiable cause. Infants with respiratory distress syndrome may become edematous without heart failure. Edema of the face and scalp may be caused by pressure from the umbilical cord around the neck, and transient localized swelling of the hands or feet may similarly be due to intrauterine pressure. Edema may be associated with heart failure. A lag in renal excretion of electrolytes and water may result in edema after a sudden large increase in intake of electrolytes, particularly with feeding of concentrated cow’s milk formulas. High-protein formulas may also cause edema as a result of the excessive renal solute load, particularly in premature infants. Rarely, idiopathic hypoproteinemia with edema lasting weeks or months is observed in term infants. The cause is unclear, and the disturbance is benign. Persistent edema of 1 or more extremities may represent congenital lymphedema (Milroy disease) or, in females, Turner syndrome. Generalized edema with hypoproteinemia may be seen in the neonatal period with congenital nephrosis and rarely with Hurler syndrome or after feeding hypoallergenic formulas to infants with cystic fibrosis of the pancreas. Sclerema is described in Chapter 639.

Hypocalcemia (Tetany) (Chapter 48)

Metabolic Bone Disease

Metabolic bone disease is a common complication in very low birthweight (VLBW) preterm infants. The smallest, sickest infants are at greatest risk. Progressive osteopenia with demineralized bones and, occasionally, pathologic fractures may develop. The major cause is inadequate intake of calcium and phosphorus to meet the requirements for growth. Poor intake of vitamin D is an additional risk factor. Contributing factors include prolonged parenteral nutrition, vitamin D and calcium malabsorption, intake of unsupplemented human milk, immobilization, and urinary calcium losses from long-term diuretic use. The serum alkaline phosphatase level is used to monitor metabolic bone disease and can be > 1,000 U/L in severe cases. Fortified human milk and formulas designed for preterm infants provide higher amounts of calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D; promote bone mineralization; and may prevent metabolic bone disease. Many extremely LBW infants will require additional oral supplements of calcium and phosphorus. Treatment of fractures requires immobilization and administration of calcium, phosphorus, and, if needed, vitamin D (not more than 1,000 IU/day unless severe cholestasis or vitamin D resistance is present). See also Chapters 48 and 564.

Substance Abuse and Neonatal Abstinence (Withdrawal)

Tremors and hyperirritability are the most prominent symptoms. The tremors may be fine or jittery and indistinguishable from those of hypoglycemia, but they are more often coarse, “flapping,” and bilateral; the limbs are frequently rigid, hyperreflexic, and resistant to flexion and extension. Irritability and hyperactivity are generally marked and may lead to skin abrasions. Other signs include wakefulness, hyperacusis, hypertonicity, tachypnea, diarrhea, vomiting, high-pitched cry, fist sucking, poor feeding with weight loss (disorganized sucking), and fever. Sneezing, yawning, hiccups, myoclonic jerks, convulsions, abnormal sleep cycles, nasal stuffiness, apnea, flushing alternating rapidly with pallor, and lacrimation are less common. The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS) is a useful way to evaluate neonates exposed to opiates or other drugs (Table 100-1). The risk of sudden infant death syndrome is higher in such neonates. The diagnosis is generally established from the history and clinical findings. Examining the urine for opiates may reveal only low levels during withdrawal, but quinine, which is often mixed with heroin, may be present in higher concentrations. Meconium testing is more accurate than neonatal urine drug testing. Hypoglycemia and hypocalcemia should be excluded.

| DOMAIN | ITEMS |

|---|---|

| Physiological | Labored breathing |

| Nasal flaring | |

| Autonomic | Sweating |

| Spit-up | |

| Hiccoughing | |

| Sneezing | |

| Nasal stuffiness | |

| Yawning | |

| CNS | Abnormal sucking |

| Choreiform movements | |

| Athetoid postures and movements | |

| Tremors | |

| Cogwheel movements | |

| Startles | |

| Hypertonia | |

| Back arching | |

| Fisting | |

| Cortical thumb | |

| Myoclonic jerks | |

| Generalized seizures | |

| Abnormal posture | |

| Skin | Pallor |

| Mottling | |

| Lividity | |

| Overall cyanosis | |

| Circumoral cyanosis | |

| Periocular cyanosis | |

| Visual | Gaze aversion during orientation |

| Pull-down during orientation | |

| Fuss/cry during orientation | |

| Obligatory following during orientation | |

| End point nystagmus during orientation | |

| Sustained spontaneous nystagmus | |

| Visual locking | |

| Hyperalertness | |

| Setting sun sign | |

| Roving eye movements | |

| Strabismus | |

| Tight blinking | |

| Other abnormal eye signs | |

| Gastrointestinal | Gagging/choking |

| Loose stools, watery stools | |

| Excessive gas, bowel sounds | |

| State | High-pitched cry |

| Monotone-pitch cry | |

| Weak cry | |

| No cry | |

| Extreme irritability | |

| Abrupt state changes | |

| Inability to achieve quiet awake state (state 4) |

CNS, central nervous system.

From Lester BM, Tronick EZ, Brazelton TB: The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scales procedures, Pediatrics 113:641–667, 2004.

100.1 Maternal Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Neonatal Behavioral Syndromes

Women of childbearing age have a combined incidence of depression and anxiety of approximately 19%. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, fluvoxamine) and, less often, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; venlafaxine, duloxetine) have been used to treat pregnant women with depression or anxiety disorders. Exposure to these agents during pregnancy may inconsistently produce congenital malformations (Chapter 90). In addition, poor neonatal adaptation has been noted with the use of many of these agents but most often with paroxetine and fluoxetine.

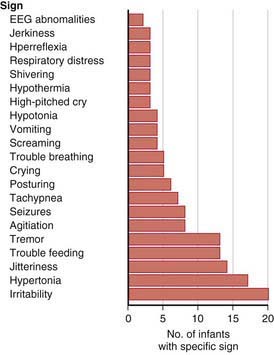

A neonatal behavioral syndrome that has features of both direct serotonin toxicity and withdrawal (cholinergic overdrive) is noted in Figure 100-1 and is characterized by central nervous system (irritability, excess or restless sleep), motor (agitation, tremor, hyperreflexia, rigidity, hypotonia or hypertonia), respiratory (nasal congestion, respiratory distress, tachypnea), gastrointestinal (diarrhea, emesis, poor feeding) and systemic (hypothermia or hyperthermia, hypoglycemia) manifestations. Most infants have only mild symptoms that resolve within 2 wk; a severe syndrome characterized by seizures, dehydration, weight loss, hyperpyrexia, and respiratory failure is present in 1%. No deaths have been reported.

Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2006;295:499-507.

Ferriera E, Carceller AM, Agogue C, et al. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine during pregnancy in term and preterm neonates. Pediatrics. 2007;119:52-59.

Kallen B. Neonate characteristics after maternal use of antidepressants in late pregnancy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:312-316.

Koren G. Discontinuation syndrome following late pregnancy exposure to antidepressants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:307-308.

Laine K, Heikkinen T, Ekblad U, et al. Effects of exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy on serotonergic symptoms in newborns and cord blood monoamine and prolactin concentrations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:720-726.

Moses-Kolko EL, Bogen D, Percel J, et al. Neonatal signs after late in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors. JAMA. 2005;293:2372-2383.

Sanz EJ, De-las-Cuevas C, Kiuru A, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnant women and neonatal withdrawal syndrome: a database analysis. Lancet. 2005;365:482-487.

100.2 Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

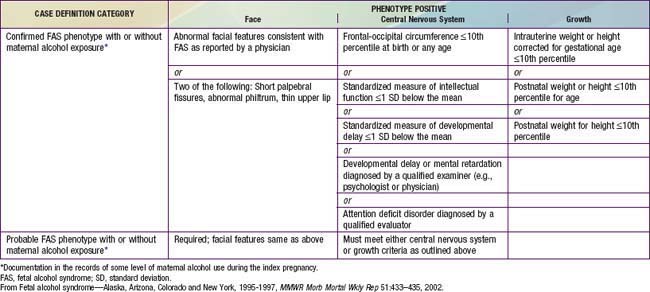

High levels of alcohol ingestion during pregnancy can be damaging to embryonic and fetal development. A specific pattern of malformation identified as fetal alcohol syndrome has been documented, and major and minor components of the syndrome are expressed in 1-2 infants/1,000 live births (see Table 100-2). Both moderate and high levels of alcohol intake during early pregnancy may result in alterations in growth and morphogenesis of the fetus; the greater the intake, the more severe the signs. The risk of abnormality for infants born to heavy drinkers is twice that for infants born to moderate drinkers; in one study, 32% of infants born to heavy drinkers had congenital anomalies, compared with 9% of those born to abstinent mothers and 14% of those born to moderate drinkers. Additional maternal risk factors associated with fetal alcohol syndrome are advanced maternal age, low socioeconomic status, poor psychologic indicators, and binge drinking.

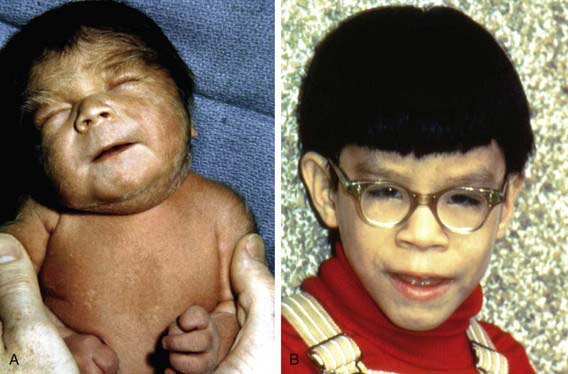

Characteristics of fetal alcohol syndrome include (1) prenatal onset and persistence of growth deficiency for length, weight, and head circumference; (2) facial abnormalities, including short palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, maxillary hypoplasia, micrognathia, smooth philtrum, and a thin, smooth upper lip (Fig. 100-2); (3) cardiac defects, primarily septal defects; (4) minor joint and limb abnormalities, including some restriction of movement and altered palmar crease patterns; and (5) delay of development and mental deficiency varying from borderline to severe (Table 100-2). Fetal alcohol syndrome is a common identifiable cause of mental retardation. The severity of dysmorphogenesis may range from severely affected infants with full manifestations of fetal alcohol syndrome to those mildly affected with only a few manifestations.

Centers for Disease Control. Alcohol use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age—United States, 1991–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:529-532.

Guerrini I, Jackson S, Keaney F. Pregnancy and alcohol misuse. BMJ. 2009;338:b845.

Iveli MF, Morales S, Rebolledo A, et al. Effects of light ethanol consumption during pregnancy: increased frequency of minor anomalies in the newborn and altered contractility of umbilical cord artery. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:456-461.

Jacobson SW, Carr LG, Croxford J, et al. Protective effects of the alcohol dehydrogenase-ASH1B allele in children exposed to alcohol during pregnancy. J Pediatr. 2006;148:30-37.

Kable JA, Coles CD. The impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on neurophysiological encoding of environmental events at six months. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:489-496.

Malisza KL, Allman AA, Shiloff D, et al. Evaluation of spatial working memory function in children and adults with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:1150-1157.

Moore ES, Ward RE, Jamison PL, et al. The subtle facial signs of prenatal exposure to alcohol: an anthropometric approach. J Pediatr. 2001;139:215-219.

Mukherje R, Eastman N, Turk J, Hollins S. Fetal alcohol syndrome: law and ethics. Lancet. 2007;369:1149-1150.

O’Donnell M, Nassar N, Leonard H, et al. Increasing prevalence of neonatal withdrawal syndrome: population study of maternal factors and child protection involvement. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e614-e621.

Rivkin MJ, Davis PE, Lemaster JL, et al. Volumetric MRI study of brain in children with intrauterine exposure of cocaine, alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. Pediatrics. 2008;121:741-750.

Sood B, Delaney-Black V, Covington C, et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure and childhood behavior at age 6 to 7 years I: dose-response effect. Pediatrics. 2001;108:e34.

Backstrom MC, Kuusela AL, Maki R. Metabolic bone disease of prematurity. Ann Med. 1996;28:275-282.

Bandstra ES, Morrow CE, Anthony JC, et al. Intrauterine growth of full-term infants: impact of prenatal cocaine exposure. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1309-1319.

Coyle MG, Ferguson A, Lagasse L, et al. Diluted tincture of opium (DTO) and phenobarbital versus DTO alone for neonatal opiate withdrawal in term infants. J Pediatr. 2002;140:561-564.

Coyle MG, Ferguson A, Lagasse L, et al. Neurobehavioral effects of treatment for opiate withdrawal. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F73-F74.

Fewtrell MS, Cole TJ, Bishop NJ, et al. Neonatal factors predicting childhood height in preterm infants: evidence for a persisting effect of early metabolic bone disease? J Pediatr. 2000;137:668-673.

Godding V, Bonnier C, Fiasse L, et al. Does in utero exposure to heavy maternal smoking induce nicotine withdrawal symptoms in neonates? Pediatr Res. 2004;55:645-651.

Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, Willford J, et al. Prenatal marijuana exposure and intelligence test performance at age 6. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:254-263.

Hurt H, Giannetta JM, Korczykowski M, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging and working memory in adolescents with gestational cocaine exposure. J Pediatr. 2008;152:371-377.

Jackson L, Ting A, Mckay S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of morphine versus phenobarbitone for neonatal abstinence syndrome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F300-F304.

Jansson LM, Choo R, Velez ML, et al. Methadone maintenance and breastfeeding in the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 2008;121:106-114.

Jentink J, Dolk H, Loane MA, et al. Intrauterine exposure to carbamazepine and specific congenital malformations: systematic review and case-control study. BMJ. 2010;341:c6581.

Jentink J, Loane MA, Dolk H, et al. Valproic acid monotherapy in pregnancy and major congenital malformations. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2185-2193.

Johnson K, Gerada C, Greenough A. Treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F2-F5.

Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methasone or buprenopphine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2320-2330.

Kraft WK, Gibson E, Dysart K, et al. Sublingual buprenorphine for treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e601-e607.

Lester BM, Tronick EZ, Brazelton TB. The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale procedures. Pediatrics. 2004;113:641-667.

Levine TP, Liu J, Dad A, et al. Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on special education in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e83-e91.

McCall EM, Alderdice FA, Halliday HL, et al: Interventions to prevent hypothermia at birth in preterm and /or low birthweight infants, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (23):CD004210, 2008.

Osborn DA, Jeffery HE, Cole MJ: Opiate treatment for opiate withdrawal in newborn infants, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD002059, 2005.

Osborn DA, Jeffery HE, Cole MJ: Sedatives for opiate withdrawal in newborn infants, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD002053, 2005.

Ostrea EMJr, Knapp DK, Tannenbaum L, et al. Estimates of illicit drug use during pregnancy by maternal interview, hair analysis, and meconium analysis. J Pediatr. 2001;138:344-348.

Pedersen LH, Henriksen TB, Olsen J. Fetal exposure to antidepressants and normal milestone development at 6 and 19 months of age. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e600-e608.

Ryan S. Nutritional aspects of metabolic bone disease in the newborn. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:F145-F148.

Shankaran S, Das A, Bauer CR, et al. Association between patterns of maternal substance use and infant birth weight, length, and head circumference. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e226-e234.

Singer LT, Nelson S, Short E, et al. Prenatal cocaine exposure: drug and environmental effects at 9 years. J Pediatr. 2008;153:105-111.

Smith LM, La Gasse LL, Derauf C, et al. The infant development, environment, and lifestyle study: effects of prenatal methamphetamine exposure, polydrug exposure, and poverty or intrauterine growth. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1149-1156.

Tunell R. Prevention of neonatal cold injury in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:308-310.

Velez ML, Jansson LM, Schroeder J, et al. Prenatal methadone exposure and neonatal neurobehavioral functioning. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:704-709.

Wang LH, Lin HC, Lin CC, et al. Increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women receiving zolpidem during pregnancy. Clin Pharm Therapeutics. 2010;88(3):369-374.