FIGURE 351-8 Wireless capsule endoscopy image in a patient with Crohn’s disease of the ileum shows ulcerations and narrowing of the intestinal lumen. (Courtesy of Dr. S. Reddy, Gastroenterology Division, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; with permission.)

In CD, early radiographic findings in the small bowel include thickened folds and aphthous ulcerations. “Cobblestoning” from longitudinal and transverse ulcerations most frequently involves the small bowel. In more advanced disease, strictures, fistulas, inflammatory masses, and abscesses may be detected. The earliest macroscopic findings of colonic CD are aphthous ulcers. These small ulcers are often multiple and separated by normal intervening mucosa. As the disease progresses, aphthous ulcers become enlarged, deeper, and occasionally connected to one another, forming longitudinal stellate, serpiginous, and linear ulcers (see Fig. 345-4B).

The transmural inflammation of CD leads to decreased luminal diameter and limited distensibility. As ulcers progress deeper, they can lead to fistula formation. The radiographic “string sign” represents long areas of circumferential inflammation and fibrosis, resulting in long segments of luminal narrowing. The segmental nature of CD results in wide gaps of normal or dilated bowel between involved segments.

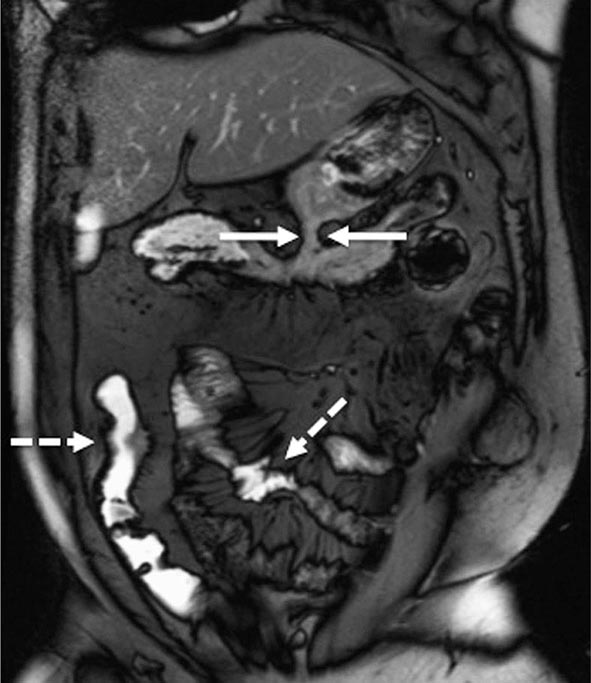

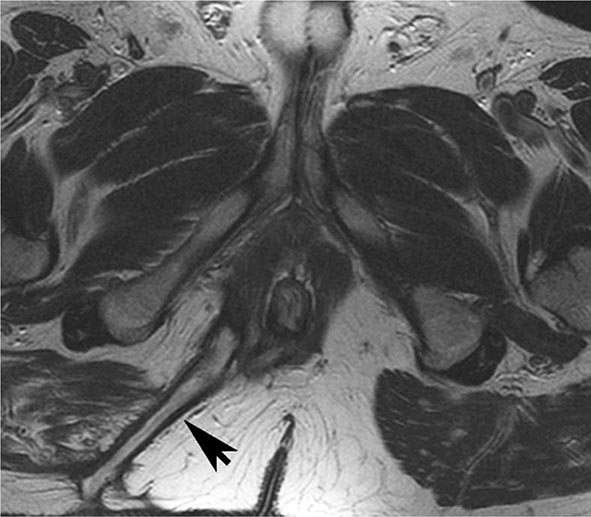

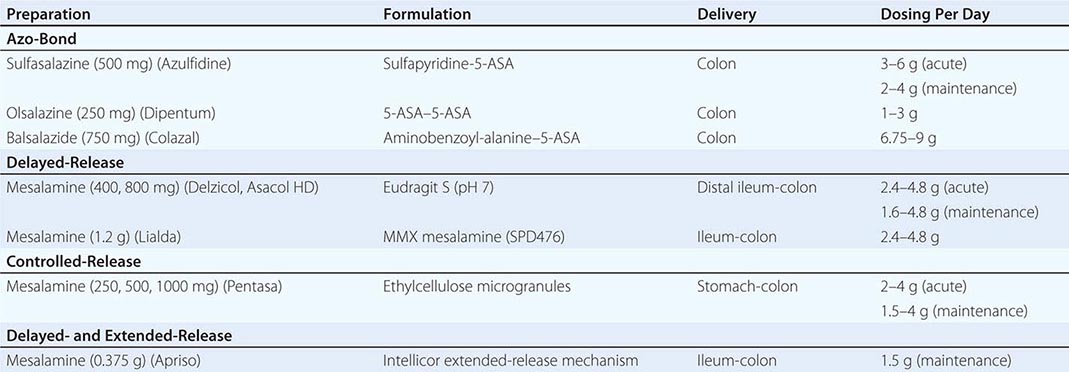

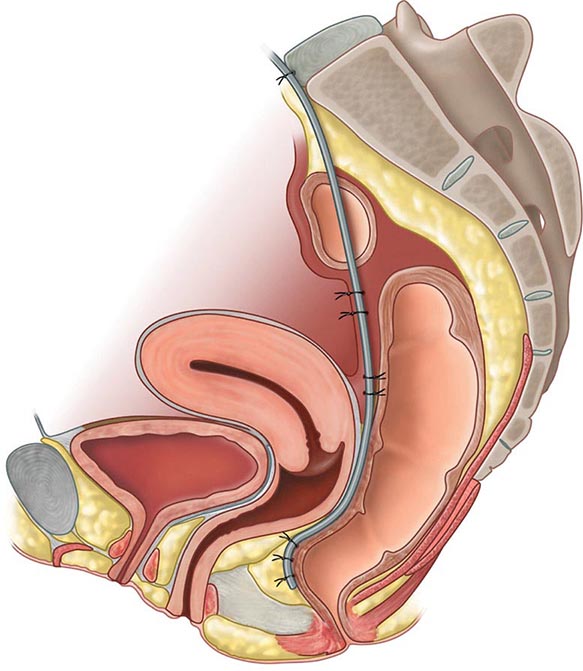

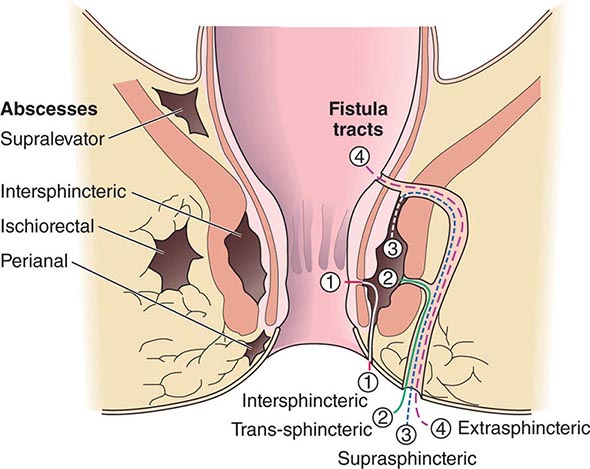

Both CT and MRI of the small bowel can be performed by enterography (CTE or MRE), using oral and IV contrast, as well as enteroclysis. Although institutional preference guides technique selection, CTE and MRE tend to be preferred over enteroclysis due to ease and patient preference. Although CTE, MRE, and small-bowel follow-through (SBFT) have been shown to be equally accurate in the identification of active small-bowel inflammation, CTE and MRE have been shown to be superior to SBFT in the detection of extraluminal complications, including fistulas, sinus tracts, and abscesses. Currently, the use of CT scans is more common than MRI due to institutional availability and expertise. However, MRI is thought to offer superior soft tissue contrast and has the added advantage of avoiding radiation exposure changes (Figs. 351-9 and 351-10). The lack of ionizing radiation is particularly appealing in younger patients and when monitoring response to therapy where serial images will be obtained. Either CTE or MRE is the first-line test for the evaluation of suspected CD and its complications. Pelvic MRI is superior to CT for demonstrating pelvic lesions such as ischiorectal abscesses and perianal fistulae (Fig. 351-11).

FIGURE 351-9 A coronal magnetic resonance image was obtained using a half Fourier single-shot T2-weighted acquisition with fat saturation in a 27-year-old pregnant (23 weeks’ gestation) woman. The patient had Crohn’s disease and was maintained on 6-mercaptopurine and prednisone. She presented with abdominal pain, distension, vomiting, and small-bowel obstruction. The image reveals a 7- to 10-cm long stricture at the terminal ileum (white arrows) causing obstruction and significant dilatation of the proximal small bowel (white asterisk). A fetus is seen in the uterus (dashed white arrows). (Courtesy of Drs. J. F. B. Chick and P. B. Shyn, Abdominal Imaging and Intervention, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; with permission.)

FIGURE 351-10 A coronal balanced, steady-state, free precession, T2-weighted image with fat saturation was obtained in a 32-year-old man with Crohn’s disease and prior episodes of bowel obstruction, fistulas, and abscesses. He was being treated with 6-mercaptopurine and presented with abdominal distention and diarrhea. The image demonstrates a new gastrocolic fistula (solid white arrows). Multifocal involvement of the small bowel and terminal ileum is also present (dashed white arrows). (Courtesy of Drs. J. F. B. Chick and P. B. Shyn, Abdominal Imaging and Intervention, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; with permission.)

FIGURE 351-11 Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image obtained in a 37-year-old man with Crohn’s disease shows a linear fluid-filled perianal fistula (arrow) in the right ischioanal fossa. (Courtesy of Dr. K. Mortele, Gastrointestinal Radiology, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; with permission.)

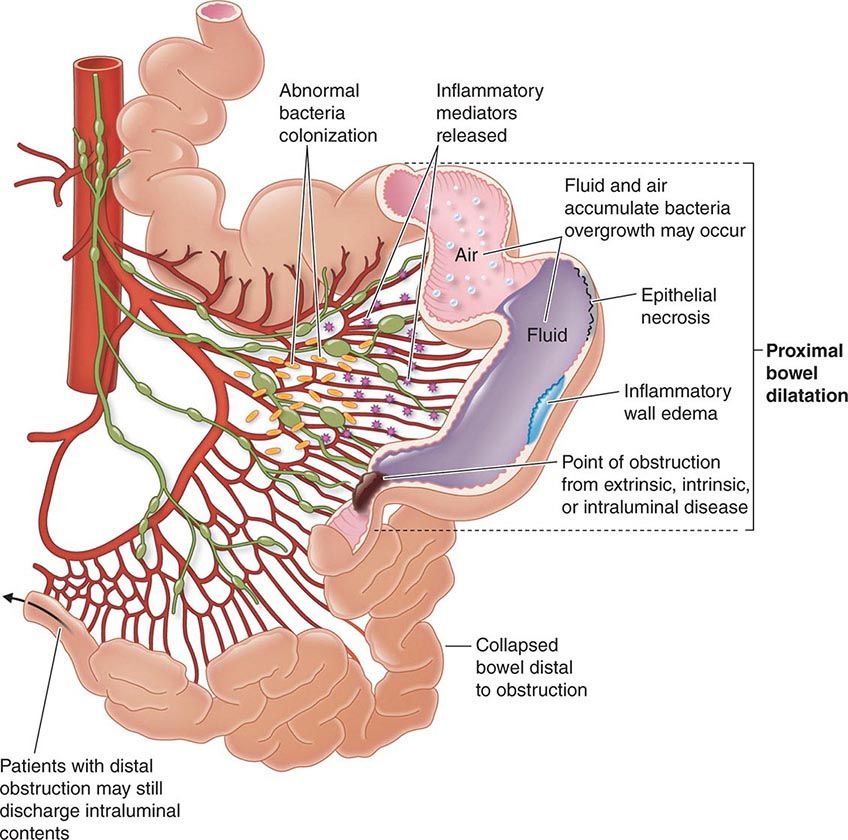

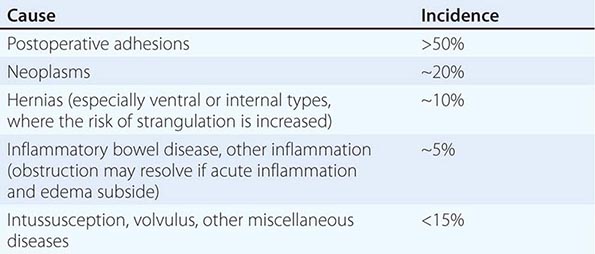

Complications Because CD is a transmural process, serosal adhesions develop that provide direct pathways for fistula formation and reduce the incidence of free perforation. Perforation occurs in 1–2% of patients, usually in the ileum but occasionally in the jejunum or as a complication of toxic megacolon. The peritonitis of free perforation, especially colonic, may be fatal. Intraabdominal and pelvic abscesses occur in 10–30% of patients with CD at some time in the course of their illness. CT-guided percutaneous drainage of the abscess is standard therapy. Despite adequate drainage, most patients need resection of the offending bowel segment. Percutaneous drainage has an especially high failure rate in abdominal wall abscesses. Systemic glucocorticoid therapy increases the risk of intraabdominal and pelvic abscesses in CD patients who have never had an operation. Other complications include intestinal obstruction in 40%, massive hemorrhage, malabsorption, and severe perianal disease.

Serologic Markers Patients with CD show a wide variation in the way they present and progress over time. Some patients present with mild disease activity and do well with generally safe and mild medications, but many others exhibit more severe disease and can develop serious complications that will require surgery. Current and developing biologic therapies can help halt progression of disease and give patients with moderate to severe CD a better quality of life. There are potential risks of biologic therapies such as infection and malignancy, and it would be optimal to determine at the time of diagnosis which patients will require more aggressive medical therapy. This same argument holds true for UC patients as well.

Subsets of patients with differing immune responses to microbial antigens have been described, and serology is often tested for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCAs) and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCAs). Unfortunately, these serologic markers are only marginally useful in helping to make the diagnosis of UC or CD and in predicting the course of disease. For success in diagnosing IBD and in differentiating between CD and UC, the efficacy of these serologic tests depends on the prevalence of IBD in a specific population. pANCA positivity is found in about 60–70% of UC patients and 5–10% of CD patients; 5–15% of first-degree relatives of UC patients are pANCA positive, whereas only 2–3% of the general population is pANCA positive. Sixty to 70% of CD patients, 10–15% of UC patients, and up to 5% of non-IBD controls are ASCA positive. In a patient population with a combined prevalence of UC and CD of 62%, pANCA/ASCA serology showed a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 94%. Positive and negative predictive values (PPVs and NPVs) for pANCA/ASCA also vary based on the prevalence of IBD in a given population. For the patient population with a prevalence of IBD of 62%, the PPV is 94%, and the NPV is 63%.

Other serologic tests include antibodies to Escherichia coli outer membrane porin protein C (OmpC), which is found in 55% of CD patients; antibodies to I2, a homologue of the bacterial transcription factor families from a Pseudomonas fluorescens–associated sequence that is found in 50–54% of CD patients; and anti-flagellin (anti-CBir1) antibodies, which have been identified in approximately 50% of CD patients.

Children with CD positive for all four immune responses (ASCA+, OmpC+, I2+, and anti-Cbir1+) may have more aggressive disease and a shorter time to progression to internal perforating and/or stricturing disease. However, larger prospective studies in both children and adults have not yet been performed and compared to CRP or other markers.

Clinical factors described at diagnosis are more helpful than serologies at predicting the natural history of CD. The initial requirements for glucocorticoid use, an age at diagnosis below 40 years and the presence of perianal disease at diagnosis, have been shown to be independently associated with subsequent disabling CD after 5 years. Except in special circumstances (such as before consideration of an ileoanal pouch anastomosis [IPAA] in a patient with indeterminate colitis), serologic markers have only minimal clinical utility.

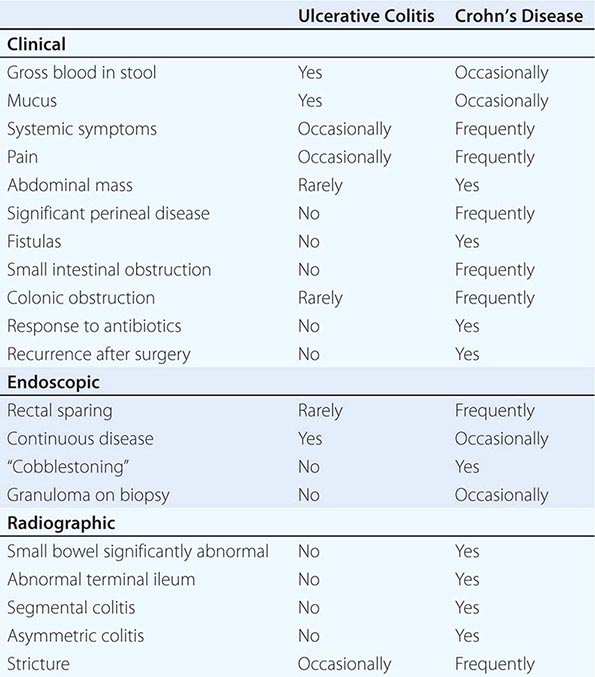

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF UC AND CD

UC and CD have similar features to many other diseases. In the absence of a key diagnostic test, a combination of features is used (Table 351-5). Once a diagnosis of IBD is made, distinguishing between UC and CD is impossible initially in up to 15% of cases. These are termed indeterminate colitis. Fortunately, in most cases, the true nature of the underlying colitis becomes evident later in the course of the patient’s disease. Approximately 5% (range 1–20%) of colon resection specimens are difficult to classify as either UC or CD because they exhibit overlapping histologic features.

|

DIFFERENT CLINICAL, ENDOSCOPIC, AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES |

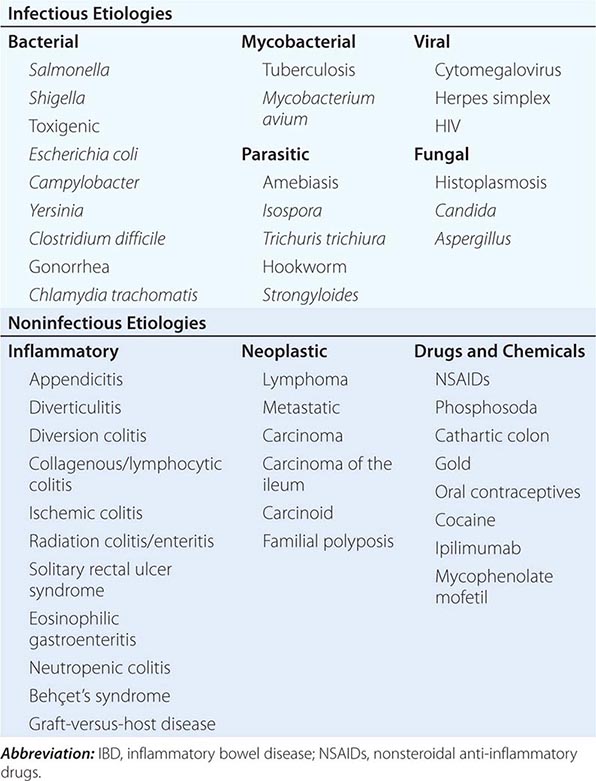

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Infections of the small intestines and colon can mimic CD or UC. They may be bacterial, fungal, viral, or protozoal in origin (Table 351-6). Campylobacter colitis can mimic the endoscopic appearance of severe UC and can cause a relapse of established UC. Salmonella can cause watery or bloody diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Shigellosis causes watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever followed by rectal tenesmus and by the passage of blood and mucus per rectum. All three are usually self-limited, but 1% of patients infected with Salmonella become asymptomatic carriers. Yersinia enterocolitica infection occurs mainly in the terminal ileum and causes mucosal ulceration, neutrophil invasion, and thickening of the ileal wall. Other bacterial infections that may mimic IBD include C. difficile, which presents with watery diarrhea, tenesmus, nausea, and vomiting; and E. coli, three categories of which can cause colitis. These are enterohemorrhagic, enteroinvasive, and enteroadherent E. coli, all of which can cause bloody diarrhea and abdominal tenderness. Diagnosis of bacterial colitis is made by sending stool specimens for bacterial culture and C. difficile toxin analysis. Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and syphilis can also cause proctitis.

|

DISEASES THAT MIMIC IBD |

GI involvement with mycobacterial infection occurs primarily in the immunosuppressed patient but may occur in patients with normal immunity. Distal ileal and cecal involvement predominates, and patients present with symptoms of small-bowel obstruction and a tender abdominal mass. The diagnosis is made most directly by colonoscopy with biopsy and culture. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection occurs in advanced stages of HIV infection and in other immunocompromised states; it usually manifests as a systemic infection with diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, fever, and malabsorption. Diagnosis is established by acid-fast smear and culture of mucosal biopsies.

Although most of the patients with viral colitis are immunosuppressed, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes simplex proctitis may occur in immunocompetent individuals. CMV occurs most commonly in the esophagus, colon, and rectum but may also involve the small intestine. Symptoms include abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, fever, and weight loss. With severe disease, necrosis and perforation can occur. Diagnosis is made by identification of characteristic intranuclear inclusions in mucosal cells on biopsy. Herpes simplex infection of the GI tract is limited to the oropharynx, anorectum, and perianal areas. Symptoms include anorectal pain, tenesmus, constipation, inguinal adenopathy, difficulty with urinary voiding, and sacral paresthesias. Diagnosis is made by rectal biopsy with identification of characteristic cellular inclusions and viral culture. HIV itself can cause diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia. Small intestinal biopsies show partial villous atrophy; small bowel bacterial overgrowth and fat malabsorption may also be noted.

Protozoan parasites include Isospora belli, which can cause a self-limited infection in healthy hosts but causes a chronic profuse, watery diarrhea, and weight loss in AIDS patients. Entamoeba histolytica or related species infect about 10% of the world’s population; symptoms include abdominal pain, tenesmus, frequent loose stools containing blood and mucus, and abdominal tenderness. Colonoscopy reveals focal punctate ulcers with normal intervening mucosa; diagnosis is made by biopsy or serum amebic antibodies. Fulminant amebic colitis is rare but has a mortality rate of >50%.

Other parasitic infections that may mimic IBD include hookworm (Necator americanus), whipworm (Trichuris trichiura), and Strongyloides stercoralis. In severely immunocompromised patients, Candida or Aspergillus can be identified in the submucosa. Disseminated histoplasmosis can involve the ileocecal area.

NONINFECTIOUS DISEASES

Diverticulitis can be confused with CD clinically and radiographically. Both diseases cause fever, abdominal pain, tender abdominal mass, leukocytosis, elevated ESR, partial obstruction, and fistulas. Perianal disease or ileitis on small-bowel series favors the diagnosis of CD. Significant endoscopic mucosal abnormalities are more likely in CD than in diverticulitis. Endoscopic or clinical recurrence following segmental resection favors CD. Diverticular-associated colitis is similar to CD, but mucosal abnormalities are limited to the sigmoid and descending colon.

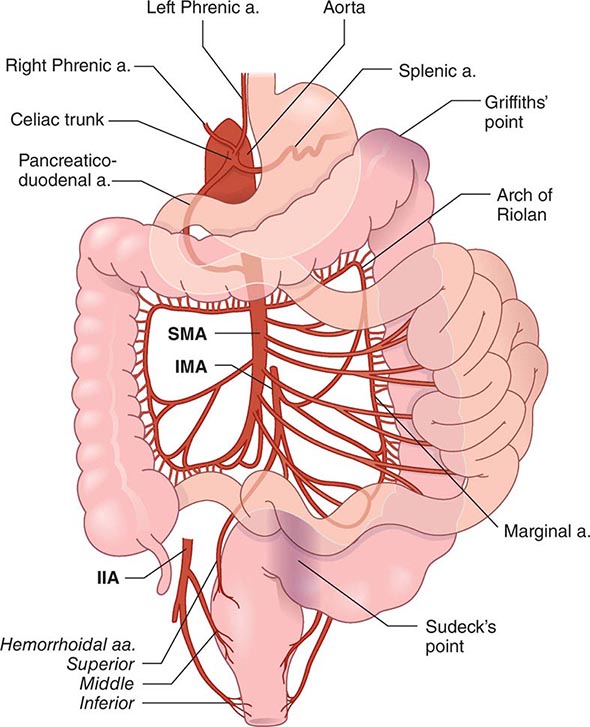

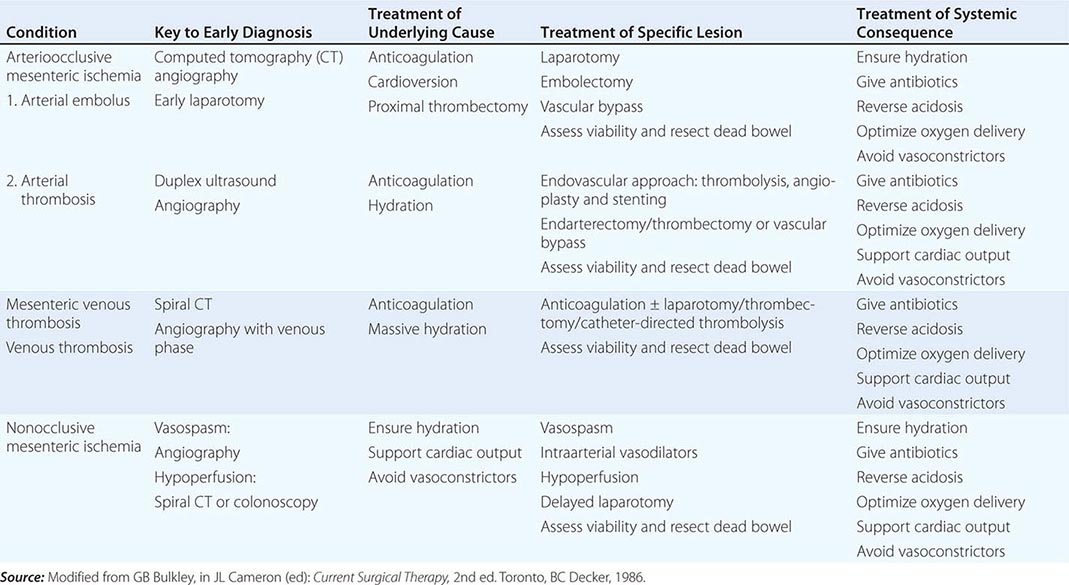

Ischemic colitis is commonly confused with IBD. The ischemic process can be chronic and diffuse, as in UC, or segmental, as in CD. Colonic inflammation due to ischemia may resolve quickly or may persist and result in transmural scarring and stricture formation. Ischemic bowel disease should be considered in the elderly following abdominal aortic aneurysm repair or when a patient has a hypercoagulable state or a severe cardiac or peripheral vascular disorder. Patients usually present with sudden onset of left lower quadrant pain, urgency to defecate, and the passage of bright red blood per rectum. Endoscopic examination often demonstrates a normal-appearing rectum and a sharp transition to an area of inflammation in the descending colon and splenic flexure.

The effects of radiotherapy on the GI tract can be difficult to distinguish from IBD. Acute symptoms can occur within 1–2 weeks of starting radiotherapy. When the rectum and sigmoid are irradiated, patients develop bloody, mucoid diarrhea and tenesmus, as in distal UC. With small-bowel involvement, diarrhea is common. Late symptoms include malabsorption and weight loss. Stricturing with obstruction and bacterial overgrowth may occur. Fistulas can penetrate the bladder, vagina, or abdominal wall. Flexible sigmoidoscopy reveals mucosal granularity, friability, numerous telangiectasias, and occasionally discrete ulcerations. Biopsy can be diagnostic.

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome is uncommon and can be confused with IBD. It occurs in persons of all ages and may be caused by impaired evacuation and failure of relaxation of the puborectalis muscle. Single or multiple ulcerations may arise from anal sphincter overactivity, higher intrarectal pressures during defecation, and digital removal of stool. Patients complain of constipation with straining and pass blood and mucus per rectum. Other symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, tenesmus, and perineal pain. Ulceration as large as 5 cm in diameter is usually seen anteriorly or anterior-laterally 3–15 cm from the anal verge. Biopsies can be diagnostic.

Several types of colitis are associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including de novo colitis, reactivation of IBD, and proctitis caused by use of suppositories. Most patients with NSAID-related colitis present with diarrhea and abdominal pain, and complications include stricture, bleeding, obstruction, perforation, and fistulization. Withdrawal of these agents is crucial, and in cases of reactivated IBD, standard therapies are indicated.

There are complications of two drugs used in a hospital setting that mimic IBD. The first is ipilimumab, a drug that targets cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and reverses T cell inhibition and is used to treat metastatic melanoma; ipilimumab has an incidence of IBD in 0.0017 cases per 100 person-years. Ipilimumab-induced colitis is typically treated with glucocorticoids or infliximab. The second is mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), an immunosuppressive agent commonly used to prevent posttransplant rejection. The colitis associated with MMF is common and can occur in more than one-third of patients taking the drug. Treatment is dose reduction or cessation of the drug.

THE ATYPICAL COLITIDES

Two atypical colitides—collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis—have completely normal endoscopic appearances. Collagenous colitis has two main histologic components: increased subepithelial collagen deposition and colitis with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes. The female to male ratio is 9:1, and most patients present in the sixth or seventh decades of life. The main symptom is chronic watery diarrhea. Treatments range from sulfasalazine or mesalamine and diphenoxylate/atropine (Lomotil) to bismuth to budesonide to prednisone or azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine for refractory disease. Risk factors include smoking; use of NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors, or beta blockers; and a history of autoimmune disease.

Lymphocytic colitis has features similar to collagenous colitis, including age at onset and clinical presentation, but it has almost equal incidence in men and women and no subepithelial collagen deposition on pathologic section. However, intraepithelial lymphocytes are increased. Use of sertraline (but not beta blockers) is an additional risk factor. The frequency of celiac disease is increased in lymphocytic colitis and ranges from 9 to 27%. Celiac disease should be excluded in all patients with lymphocytic colitis, particularly if diarrhea does not respond to conventional therapy. Treatment is similar to that of collagenous colitis with the exception of a gluten-free diet for those who have celiac disease.

Diversion colitis is an inflammatory process that arises in segments of the large intestine that are excluded from the fecal stream. It usually occurs in patients with ileostomy or colostomy when a mucus fistula or a Hartmann’s pouch has been created. Clinically, patients have mucus or bloody discharge from the rectum. Erythema, granularity, friability, and, in more severe cases, ulceration can be seen on endoscopy. Histopathology shows areas of active inflammation with foci of cryptitis and crypt abscesses. Crypt architecture is normal, which differentiates it from UC. It may be impossible to distinguish from CD. Short-chain fatty acid enemas may help in diversion colitis, but the definitive therapy is surgical reanastomosis.

EXTRAINTESTINAL MANIFESTATIONS

Up to one-third of IBD patients have at least one extraintestinal disease manifestation.

DERMATOLOGIC

Erythema nodosum (EN) occurs in up to 15% of CD patients and 10% of UC patients. Attacks usually correlate with bowel activity; skin lesions develop after the onset of bowel symptoms, and patients frequently have concomitant active peripheral arthritis. The lesions of EN are hot, red, tender nodules measuring 1–5 cm in diameter and are found on the anterior surface of the lower legs, ankles, calves, thighs, and arms. Therapy is directed toward the underlying bowel disease.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is seen in 1–12% of UC patients and less commonly in Crohn’s colitis. Although it usually presents after the diagnosis of IBD, PG may occur years before the onset of bowel symptoms, run a course independent of the bowel disease, respond poorly to colectomy, and even develop years after proctocolectomy. It is usually associated with severe disease. Lesions are commonly found on the dorsal surface of the feet and legs but may occur on the arms, chest, stoma, and even the face. PG usually begins as a pustule and then spreads concentrically to rapidly undermine healthy skin. Lesions then ulcerate, with violaceous edges surrounded by a margin of erythema. Centrally, they contain necrotic tissue with blood and exudates. Lesions may be single or multiple and grow as large as 30 cm. They are sometimes very difficult to treat and often require IV antibiotics, IV glucocorticoids, dapsone, azathioprine, thalidomide, IV cyclosporine, or infliximab.

Other dermatologic manifestations include pyoderma vegetans, which occurs in intertriginous areas; pyostomatitis vegetans, which involves the mucous membranes; Sweet syndrome, a neutrophilic dermatosis; and metastatic CD, a rare disorder defined by cutaneous granuloma formation. Psoriasis affects 5–10% of patients with IBD and is unrelated to bowel activity consistent with the potential shared immunogenetic basis of these diseases. Perianal skin tags are found in 75–80% of patients with CD, especially those with colon involvement. Oral mucosal lesions, seen often in CD and rarely in UC, include aphthous stomatitis and “cobblestone” lesions of the buccal mucosa.

RHEUMATOLOGIC

Peripheral arthritis develops in 15–20% of IBD patients, is more common in CD, and worsens with exacerbations of bowel activity. It is asymmetric, polyarticular, and migratory and most often affects large joints of the upper and lower extremities. Treatment is directed at reducing bowel inflammation. In severe UC, colectomy frequently cures the arthritis.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) occurs in about 10% of IBD patients and is more common in CD than UC. About two-thirds of IBD patients with AS express the HLA-B27 antigen. The AS activity is not related to bowel activity and does not remit with glucocorticoids or colectomy. It most often affects the spine and pelvis, producing symptoms of diffuse low-back pain, buttock pain, and morning stiffness. The course is continuous and progressive, leading to permanent skeletal damage and deformity. Anti-TNF therapy reduces spinal inflammation and improves functional status and quality of life.

Sacroiliitis is symmetric, occurs equally in UC and CD, is often asymptomatic, does not correlate with bowel activity, and does not always progress to AS. Other rheumatic manifestations include hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, pelvic/femoral osteomyelitis, and relapsing polychondritis.

OCULAR

The incidence of ocular complications in IBD patients is 1–10%. The most common are conjunctivitis, anterior uveitis/iritis, and episcleritis. Uveitis is associated with both UC and Crohn’s colitis, may be found during periods of remission, and may develop in patients following bowel resection. Symptoms include ocular pain, photophobia, blurred vision, and headache. Prompt intervention, sometimes with systemic glucocorticoids, is required to prevent scarring and visual impairment. Episcleritis is a benign disorder that presents with symptoms of mild ocular burning. It occurs in 3–4% of IBD patients, more commonly in Crohn’s colitis, and is treated with topical glucocorticoids.

HEPATOBILIARY

Hepatic steatosis is detectable in about one-half of the abnormal liver biopsies from patients with CD and UC; patients usually present with hepatomegaly. Fatty liver usually results from a combination of chronic debilitating illness, malnutrition, and glucocorticoid therapy. Cholelithiasis occurs in 10–35% of CD patients with ileitis or ileal resection. Gallstone formation is caused by malabsorption of bile acids, resulting in depletion of the bile salt pool and the secretion of lithogenic bile.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a disorder characterized by both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct inflammation and fibrosis, frequently leading to biliary cirrhosis and hepatic failure; approximately 5% of patients with UC have PSC, but 50–75% of patients with PSC have IBD. PSC occurs less often in patients with CD. Although it can be recognized after the diagnosis of IBD, PSC can be detected earlier or even years after proctocolectomy. Consistent with this, the immunogenetic basis for PSC appears to be overlapping but distinct from UC based on GWAS, although both IBD and PSC are commonly pANCA positive. Most patients have no symptoms at the time of diagnosis; when symptoms are present, they consist of fatigue, jaundice, abdominal pain, fever, anorexia, and malaise. The traditional gold standard diagnostic test is endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), but magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is also sensitive and specific. MRCP is reasonable as an initial diagnostic test in children and can visualize irregularities, multifocal strictures, and dilatations of all levels of the biliary tree. In patients with PSC, both ERCP and MRCP demonstrate multiple bile duct strictures alternating with relatively normal segments.

The bile acid ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol) may reduce alkaline phosphatase and serum aminotransferase levels, but histologic improvement has been marginal. High doses (25–30 mg/kg per day) may decrease the risk of colorectal dysplasia and cancer in patients with UC and PSC. Endoscopic stenting may be palliative for cholestasis secondary to bile duct obstruction. Patients with symptomatic disease develop cirrhosis and liver failure over 5–10 years and eventually require liver transplantation. PSC patients have a 10–15% lifetime risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma and then cannot be transplanted. Patients with IBD and PSC are at increased risk of colon cancer and should be surveyed yearly by colonoscopy and biopsy.

In addition, cholangiography is normal in a small percentage of patients who have a variant of PSC known as small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis. This variant (sometimes referred to as “pericholangitis”) is probably a form of PSC involving small-caliber bile ducts. It has similar biochemical and histologic features to classic PSC. It appears to have a significantly better prognosis than classic PSC, although it may evolve into classic PSC. Granulomatous hepatitis and hepatic amyloidosis are much rarer extraintestinal manifestations of IBD.

UROLOGIC

The most frequent genitourinary complications are calculi, ureteral obstruction, and ileal bladder fistulas. The highest frequency of nephrolithiasis (10–20%) occurs in patients with CD following small bowel resection. Calcium oxalate stones develop secondary to hyperoxaluria, which results from increased absorption of dietary oxalate. Normally, dietary calcium combines with luminal oxalate to form insoluble calcium oxalate, which is eliminated in the stool. In patients with ileal dysfunction, however, nonabsorbed fatty acids bind calcium and leave oxalate unbound. The unbound oxalate is then delivered to the colon, where it is readily absorbed, especially in the presence of inflammation.

METABOLIC BONE DISORDERS

Low bone mass occurs in 3–30% of IBD patients. The risk is increased by glucocorticoids, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Malabsorption and inflammation mediated by IL-1, IL-6, TNF, and other inflammatory mediators also contribute to low bone density. An increased incidence of hip, spine, wrist, and rib fractures has been noted: 36% in CD and 45% in UC. The absolute risk of an osteoporotic fracture is about 1% per person per year. Fracture rates, particularly in the spine and hip, are highest among the elderly (age >60). One study noted an OR of 1.72 for vertebral fracture and an OR of 1.59 for hip fracture. The disease severity predicted the risk of a fracture. Only 13% of IBD patients who had a fracture were on any kind of antifracture treatment. Up to 20% of bone mass can be lost per year with chronic glucocorticoid use. The effect is dosage-dependent. Budesonide may also suppress the pituitary-adrenal axis and thus carries a risk of causing osteoporosis.

Osteonecrosis is characterized by death of osteocytes and adipocytes and eventual bone collapse. The pain is aggravated by motion and swelling of the joints. It affects the hips more often than knees and shoulders, and in one series, 4.3% of patients developed osteonecrosis within 6 months of starting glucocorticoids. Diagnosis is made by bone scan or MRI, and treatment consists of pain control, cord decompression, osteotomy, and joint replacement.

THROMBOEMBOLIC DISORDERS

Patients with IBD have an increased risk of both venous and arterial thrombosis even if the disease is not active. Factors responsible for the hypercoagulable state have included abnormalities of the platelet-endothelial interaction, hyperhomocysteinemia, alterations in the coagulation cascade, impaired fibrinolysis, involvement of tissue factor-bearing microvesicles, disruption of the normal coagulation system by autoantibodies, and a genetic predisposition. A spectrum of vasculitides involving small, medium, and large vessels has also been observed.

OTHER DISORDERS

More common cardiopulmonary manifestations include endocarditis, myocarditis, pleuropericarditis, and interstitial lung disease. A secondary or reactive amyloidosis can occur in patients with long-standing IBD, especially in patients with CD. Amyloid material is deposited systemically and can cause diarrhea, constipation, and renal failure. The renal disease can be successfully treated with colchicine. Pancreatitis is a rare extraintestinal manifestation of IBD and results from duodenal fistulas; ampullary CD; gallstones; PSC; drugs such as 6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, or, very rarely, 5-ASA agents; autoimmune pancreatitis; and primary CD of the pancreas.

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE AND PREGNANCY

Patients with quiescent UC and CD have normal fertility rates; the fallopian tubes can be scarred by the inflammatory process of CD, especially on the right side because of the proximity of the terminal ileum. In addition, perirectal, perineal, and rectovaginal abscesses and fistulae can result in dyspareunia. Infertility in men can be caused by sulfasalazine but reverses when treatment is stopped. In women who have an ileoanal J pouch anastomosis, most studies show that the fertility rate is reduced to about 50–80% of normal. This is due to scarring or occlusion of the fallopian tubes secondary to pelvic inflammation.

In mild or quiescent UC and CD, fetal outcome is nearly normal. Spontaneous abortions, stillbirths, and developmental defects are increased with increased disease activity, not medications. The courses of CD and UC during pregnancy mostly correlate with disease activity at the time of conception. Patients should be in remission for 6 months before conceiving. Most CD patients can deliver vaginally, but cesarean delivery may be the preferred route of delivery for patients with anorectal and perirectal abscesses and fistulas to reduce the likelihood of fistulas developing or extending into the episiotomy scar. Unless they desire multiple children, UC patients with an IPAA should consider a cesarean delivery due to an increased risk of future fecal incontinence.

Sulfasalazine, Lialda, Apriso, Delzicol, and balsalazide are safe for use in pregnancy and nursing with the caveat that additional folate supplementation must be given with sulfasalazine. Asacol HD and olsalazine are considered by the FDA to be class C agents in pregnancy and thus not recommended. Topical 5-ASA agents are also safe during pregnancy and nursing. Glucocorticoids are generally safe for use during pregnancy and are indicated for patients with moderate to severe disease activity. The amount of glucocorticoids received by the nursing infant is minimal. The safest antibiotics to use for CD in pregnancy for short periods of time (weeks, not months) are ampicillin and cephalosporins. Metronidazole can be used in the second or third trimester. Ciprofloxacin causes cartilage lesions in immature animals and should be avoided because of the absence of data on its effects on growth and development in humans.

6-MP and azathioprine pose minimal or no risk during pregnancy, but experience is limited. If the patient cannot be weaned from the drug or has an exacerbation that requires 6-MP/azathioprine during pregnancy, she should continue the drug with informed consent. Breast milk has been shown to contain negligible levels of 6-MP/azathioprine when measured in a limited number of patients.

Little data exist on CSA in pregnancy. In a small number of patients with severe IBD treated with IV CSA during pregnancy, 80% of pregnancies were successfully completed without development of renal toxicity or congenital malformations. However, because of the lack of data, CSA should probably be avoided unless the patient would otherwise require surgery.

MTX is contraindicated in pregnancy and nursing. In a large prospective study, no increased risk of stillbirths, miscarriages, or spontaneous abortions was seen with infliximab, adalimumab, or certolizumab, which are all class B drugs. Infliximab and adalimumab are IgG1 antibodies and are actively transported across the placenta in the late second and third trimester. Infants can have serum levels of both infliximab and adalimumab up to 7 months of age, and live vaccines should be avoided during this time. Certolizumab crosses the placenta by passive diffusion, and infant serum and cord blood levels are minimal. The anti-TNF drugs are relatively safe in nursing. Miniscule levels of both infliximab and adalimumab, but not certolizumab, have been reported in breast milk. These levels are of no clinical significance. It is recommended that drugs not be switched during pregnancy unless necessitated by the medical condition of the IBD. Natalizumab is considered as a class C drug because there is limited data in pregnancy.

Surgery in UC should be performed only for emergency indications, including severe hemorrhage, perforation, and megacolon refractory to medical therapy. Total colectomy and ileostomy carry a 50% risk of postoperative spontaneous abortion. Fetal mortality is also high in CD requiring surgery. Patients with IPAAs have increased nighttime stool frequency during pregnancy that resolves postpartum. Transient small-bowel obstruction or ileus has been noted in up to 8% of patients with ileostomies.

CANCER IN INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

ULCERATIVE COLITIS

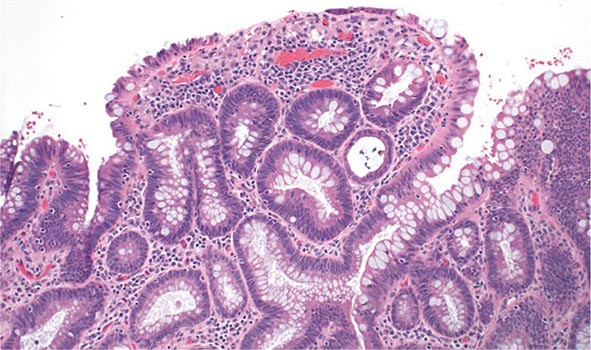

Patients with long-standing UC are at increased risk for developing colonic epithelial dysplasia and carcinoma (Fig. 351-13).

FIGURE 351-13 Medium-power view of low-grade dysplasia in a patient with chronic ulcerative colitis. Low-grade dysplastic crypts are interspersed among regenerating crypts. (Courtesy of Dr. R. Odze, Division of Gastrointestinal Pathology, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; with permission.)

The risk of neoplasia in chronic UC increases with duration and extent of disease. From one large meta-analysis, the risk of cancer in patients with UC is estimated at 2% after 10 years, 8% after 20 years, and 18% after 30 years of disease. Data from a 30-year surveillance program in the United Kingdom calculated the risk of colorectal cancer to be 7.7% at 20 years and 15.8% at 30 years of disease. The rates of colon cancer are higher than in the general population, and colonoscopic surveillance is the standard of care.

Annual or biennial colonoscopy with multiple biopsies is recommended for patients with >8–10 years of extensive colitis (greater than one-third of the colon involved) or 12–15 years of proctosigmoiditis (less than one-third but more than just the rectum) and has been widely used to screen and survey for subsequent dysplasia and carcinoma. Risk factors for cancer in UC include long-duration disease, extensive disease, family history of colon cancer, PSC, a colon stricture, and the presence of postinflammatory pseudopolyps on colonoscopy.

CROHN’S DISEASE

Risk factors for developing cancer in Crohn’s colitis are long-duration and extensive disease, bypassed colon segments, colon strictures, PSC, and family history of colon cancer. The cancer risks in CD and UC are probably equivalent for similar extent and duration of disease. In the CESAME study, a prospective observational cohort of IBD patients in France, the standardized incidence ratios of colorectal cancer were 2.2 for all IBD patients (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5–3.0; p < .001) and 7.0 for patients with long-standing extensive colitis (both Crohn’s and UC) (95% CI, 4.4–10.5; p < .001). Thus, the same endoscopic surveillance strategy used for UC is recommended for patients with chronic Crohn’s colitis. A pediatric colonoscope can be used to pass narrow strictures in CD patients, but surgery should be considered in symptomatic patients with impassable strictures.

MANAGEMENT OF DYSPLASIA AND CANCER

Dysplasia can be flat or polypoid. If flat high-grade dysplasia is encountered on colonoscopic surveillance, the usual treatment is colectomy for UC and either colectomy or segmental resection for CD. If flat low-grade dysplasia is found (Fig. 351-13), most investigators recommend immediate colectomy. Adenomas may occur coincidently in UC and CD patients with chronic colitis and can be removed endoscopically provided that biopsies of the surrounding mucosa are free of dysplasia. High-definition and high-magnification colonoscopes and dye sprays have increased the rate of dysplasia detection.

IBD patients are also at greater risk for other malignancies. Patients with CD may have an increased risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndromes. Severe, chronic, complicated perianal disease in CD patients may be associated with an increased risk of cancer in the lower rectum and anal canal (squamous cell cancers). Although the absolute risk of small-bowel adenocarcinoma in CD is low (2.2% at 25 years in one study), patients with long-standing, extensive, small-bowel disease should consider screening.

352 |

Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional bowel disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habits in the absence of detectable structural abnormalities. No clear diagnostic markers exist for IBS; thus the diagnosis of the disorder is based on clinical presentation. In 2006, the Rome II criteria for the diagnosis of IBS were revised (Table 352-1). Throughout the world, about 10–20% of adults and adolescents have symptoms consistent with IBS, and most studies show a female predominance. IBS symptoms tend to come and go over time and often overlap with other functional disorders such as fibromyalgia, headache, backache, and genitourinary symptoms. Severity of symptoms varies and can significantly impair quality of life, resulting in high health care costs. Advances in basic, mechanistic, and clinical investigations have improved our understanding of this disorder and its physiologic and psychosocial determinants. Altered gastrointestinal (GI) motility, visceral hyperalgesia, disturbance of brain-gut interaction, abnormal central processing, autonomic and hormonal events, genetic and environmental factors, and psychosocial disturbances are variably involved, depending on the individual. This progress may result in improved methods of treatment.

|

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROMEa |

aCriteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis. bDiscomfort means an uncomfortable sensation not described as pain. In pathophysiology research and clinical trials, a pain/discomfort frequency of at least 2 days a week during screening evaluation is required for subject eligibility.

Source: Adapted from GF Longstreth et al: Gastroenterology 130:1480, 2006.

CLINICAL FEATURES

IBS is a disorder that affects all ages, although most patients have their first symptoms before age 45. Older individuals have a lower reporting frequency. Women are diagnosed with IBS two to three times as often as men and make up 80% of the population with severe IBS. As indicated in Table 352-1, pain or abdominal discomfort is a key symptom for the diagnosis of IBS. These symptoms should be improved with defecation and/or have their onset associated with a change in frequency or form of stool. Painless diarrhea or constipation does not fulfill the diagnostic criteria to be classified as IBS. Supportive symptoms that are not part of the diagnostic criteria include defecation straining, urgency or a feeling of incomplete bowel movement, passing mucus, and bloating.

Abdominal Pain According to the current IBS diagnostic criteria, abdominal pain or discomfort is a prerequisite clinical feature of IBS. Abdominal pain in IBS is highly variable in intensity and location. It is frequently episodic and crampy, but it may be superimposed on a background of constant ache. Pain may be mild enough to be ignored or it may interfere with daily activities. Despite this, malnutrition due to inadequate caloric intake is exceedingly rare with IBS. Sleep deprivation is also unusual because abdominal pain is almost uniformly present only during waking hours. However, patients with severe IBS frequently wake repeatedly during the night; thus, nocturnal pain is a poor discriminating factor between organic and functional bowel disease. Pain is often exacerbated by eating or emotional stress and improved by passage of flatus or stools. In addition, female patients with IBS commonly report worsening symptoms during the premenstrual and menstrual phases.

Altered Bowel Habits Alteration in bowel habits is the most consistent clinical feature in IBS. The most common pattern is constipation alternating with diarrhea, usually with one of these symptoms predominating. At first, constipation may be episodic, but eventually it becomes continuous and increasingly intractable to treatment with laxatives. Stools are usually hard with narrowed caliber, possibly reflecting excessive dehydration caused by prolonged colonic retention and spasm. Most patients also experience a sense of incomplete evacuation, thus leading to repeated attempts at defecation in a short time span. Patients whose predominant symptom is constipation may have weeks or months of constipation interrupted with brief periods of diarrhea. In other patients, diarrhea may be the predominant symptom. Diarrhea resulting from IBS usually consists of small volumes of loose stools. Most patients have stool volumes of <200 mL. Nocturnal diarrhea does not occur in IBS. Diarrhea may be aggravated by emotional stress or eating. Stool may be accompanied by passage of large amounts of mucus. Bleeding is not a feature of IBS unless hemorrhoids are present, and malabsorption or weight loss does not occur.

Bowel pattern subtypes are highly unstable. In a patient population with ~33% prevalence rates of IBS-diarrhea predominant (IBS-D), IBS-constipation predominant (IBS-C), and IBS-mixed (IBS-M) forms, 75% of patients change subtypes and 29% switch between IBS-C and IBS-D over 1 year. The heterogeneity and variable natural history of bowel habits in IBS increase the difficulty of conducting pathophysiology studies and clinical trials.

Gas and Flatulence Patients with IBS frequently complain of abdominal distention and increased belching or flatulence, all of which they attribute to increased gas. Although some patients with these symptoms actually may have a larger amount of gas, quantitative measurements reveal that most patients who complain of increased gas generate no more than a normal amount of intestinal gas. Most IBS patients have impaired transit and tolerance of intestinal gas loads. In addition, patients with IBS tend to reflux gas from the distal to the more proximal intestine, which may explain the belching.

Some patients with bloating may also experience visible distention with increase in abdominal girth. Both symptoms are more common among female patients and in those with higher overall Somatic Symptom Checklist scores. IBS patients who experienced bloating alone have been shown to have lower thresholds for pain and desire to defecate compared to those with concomitant distention irrespective of bowel habit. When patients were grouped according to sensory threshold, hyposensitive individuals had distention significantly more than those with hypersensitivity and this was observed more in the constipation subgroup. This suggests that the pathogenesis of bloating and distention may not be the same.

Upper Gastrointestinal Symptoms Between 25 and 50% of patients with IBS complain of dyspepsia, heartburn, nausea, and vomiting. This suggests that other areas of the gut apart from the colon may be involved. Prolonged ambulant recordings of small-bowel motility in patients with IBS show a high incidence of abnormalities in the small bowel during the diurnal (waking) period; nocturnal motor patterns are not different from those of healthy controls. The overlap between dyspepsia and IBS is great. The prevalence of IBS is higher among patients with dyspepsia (31.7%) than among those who reported no symptoms of dyspepsia (7.9%). Conversely, among patients with IBS, 55.6% reported symptoms of dyspepsia. In addition, the functional abdominal symptoms can change over time. Those with predominant dyspepsia or IBS can flux between the two. Although the prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders is stable over time, the turnover in symptom status is high. Many episodes of symptom disappearance are due to subjects changing symptoms rather than total symptom resolution. Thus it is conceivable that functional dyspepsia and IBS are two manifestations of a single, more extensive digestive system disorder. Furthermore, IBS symptoms are prevalent in noncardiac chest pain patients, suggesting overlap with other functional gut disorders.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathogenesis of IBS is poorly understood, although roles of abnormal gut motor and sensory activity, central neural dysfunction, psychological disturbances, mucosal inflammation, stress, and luminal factors have been proposed.

Gastrointestinal Motor Abnormalities Studies of colonic myoelectrical and motor activity under unstimulated conditions have not shown consistent abnormalities in IBS. In contrast, colonic motor abnormalities are more prominent under stimulated conditions in IBS. IBS patients may exhibit increased rectosigmoid motor activity for up to 3 h after eating. Similarly, inflation of rectal balloons both in IBS-D and IBS-C patients leads to marked and prolonged distention-evoked contractile activity. Recordings from the transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon showed that the motility index and peak amplitude of high-amplitude propagating contractions (HAPCs) in diarrhea-prone IBS patients were greatly increased compared to those in healthy subjects and were associated with rapid colonic transit and accompanied by abdominal pain.

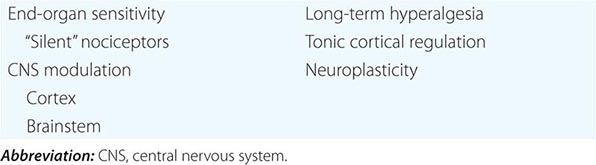

Visceral Hypersensitivity As with studies of motor activity, IBS patients frequently exhibit exaggerated sensory responses to visceral stimulation. The frequency of perceptions of food intolerance is at least twofold more common than in the general population. Postprandial pain has been temporally related to entry of the food bolus into the cecum in 74% of patients. On the other hand, prolonged fasting in IBS patients is often associated with significant improvement in symptoms. Rectal balloon inflation produces nonpainful and painful sensations at lower volumes in IBS patients than in healthy controls without altering rectal tension, suggestive of visceral afferent dysfunction in IBS. Similar studies show gastric and esophageal hypersensitivity in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia and noncardiac chest pain, raising the possibility that these conditions have a similar pathophysiologic basis. Lipids lower the thresholds for the first sensation of gas, discomfort, and pain in IBS patients. Hence, postprandial symptoms in IBS patients may be explained in part by a nutrient-dependent exaggerated sensory component of the gastrocolonic response. In contrast to enhanced gut sensitivity, IBS patients do not exhibit heightened sensitivity elsewhere in the body. Thus, the afferent pathway disturbances in IBS appear to be selective for visceral innervation with sparing of somatic pathways. The mechanisms responsible for visceral hypersensitivity are still under investigation. It has been proposed that these exaggerated responses may be due to (1) increased end-organ sensitivity with recruitment of “silent” nociceptors; (2) spinal hyperexcitability with activation of nitric oxide and possibly other neurotransmitters; (3) endogenous (cortical and brainstem) modulation of caudad nociceptive transmission; and (4) over time, the possible development of long-term hyperalgesia due to development of neuroplasticity, resulting in permanent or semipermanent changes in neural responses to chronic or recurrent visceral stimulation (Table 352-2).

|

PROPOSED MECHANISMS FOR VISCERAL HYPERSENSITIVITY |

Central Neural Dysregulation The role of central nervous system (CNS) factors in the pathogenesis of IBS is strongly suggested by the clinical association of emotional disorders and stress with symptom exacerbation and the therapeutic response to therapies that act on cerebral cortical sites. Functional brain imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have shown that in response to distal colonic stimulation, the mid-cingulate cortex—a brain region concerned with attention processes and response selection—shows greater activation in IBS patients. Modulation of this region is associated with changes in the subjective unpleasantness of pain. In addition, IBS patients also show preferential activation of the prefrontal lobe, which contains a vigilance network within the brain that increases alertness. These may represent a form of cerebral dysfunction leading to the increased perception of visceral pain.

Abnormal Psychological Features Abnormal psychiatric features are recorded in up to 80% of IBS patients, especially in referral centers; however, no single psychiatric diagnosis predominates. Most of these patients demonstrated exaggerated symptoms in response to visceral distention, and this abnormality persists even after exclusion of psychological factors.

Psychological factors influence pain thresholds in IBS patients, as stress alters sensory thresholds. An association between prior sexual or physical abuse and development of IBS has been reported. Abuse is associated with greater pain reporting, psychological distress, and poor health outcome. Brain functional MRI studies show greater activation of the posterior and middle dorsal cingulate cortex, which is implicated in affect processing in IBS patients with a past history of sexual abuse.

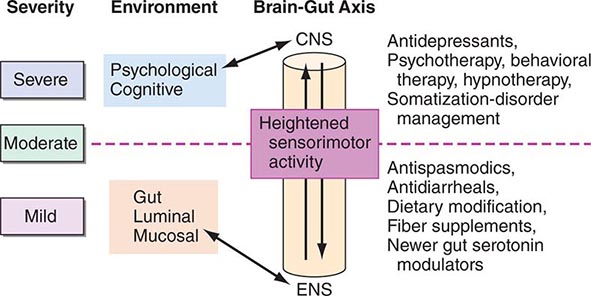

Thus, patients with IBS frequently demonstrate increased motor reactivity of the colon and small bowel to a variety of stimuli and altered visceral sensation associated with lowered sensation thresholds. These may result from CNS–enteric nervous system dysregulation (Fig. 352-1).

FIGURE 352-1 Therapeutic targets for irritable bowel syndrome. Patients with mild to moderate symptoms usually have intermittent symptoms that correlate with altered gut physiology. Treatments include gut-acting pharmacologic agents such as antispasmodics, antidiarrheals, fiber supplements, and gut serotonin modulators. Patients who have severe symptoms usually have constant pain and psychosocial difficulties. This group of patients is best managed with antidepressants and other psychosocial treatments. CNS, central nervous system; ENS, enteric nervous system.

Postinfectious IBS IBS may be induced by GI infection. In an investigation of 544 patients with confirmed bacterial gastroenteritis, one-quarter developed IBS subsequently. Conversely, about a third of IBS patients experienced an acute “gastroenteritis-like” illness at the onset of their chronic IBS symptomatology. This group of “postinfective” IBS occurs more commonly in females and affects younger rather than older patients. Risk factors for developing postinfectious IBS include, in order of importance, prolonged duration of initial illness, toxicity of infecting bacterial strain, smoking, mucosal markers of inflammation, female gender, depression, hypochondriasis, and adverse life events in the preceding 3 months. Age older than 60 years might protect against postinfectious IBS, whereas treatment with antibiotics has been associated with increased risk. The microbes involved in the initial infection are Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella. Those patients with Campylobacter infection who are toxin-positive are more likely to develop postinfective IBS. Increased rectal mucosal enteroendocrine cells, T lymphocytes, and increased gut permeability are acute changes following Campylobacter enteritis that could persist for more than a year and may contribute to postinfective IBS.

Immune Activation and Mucosal Inflammation Some patients with IBS display persistent signs of low-grade mucosal inflammation with activated lymphocytes, mast cells, and enhanced expression of proinflammatory cytokines. These abnormalities may contribute to abnormal epithelial secretion and visceral hypersensitivity. There is increasing evidence that some members of the superfamily of transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channels such as TRPV1 (vanilloid) channels are central to the initiation and persistence of visceral hypersensitivity. Mucosal inflammation can lead to increased expression of TRPV1 in the enteric nervous system. Enhanced expression of TRPV1 channels in the sensory neurons of the gut has been observed in IBS, and such expression appears to correlate with visceral hypersensitivity and abdominal pain. Interestingly, clinical studies have also shown increased intestinal permeability in patients with IBS-D. Psychological stress and anxiety can increase the release of proinflammatory cytokine, and this in turn may alter intestinal permeability. This provides a functional link between psychological stress, immune activation, and symptom generation in patients with IBS.

Altered Gut Flora A high prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in IBS patients has been noted based on positive lactulose hydrogen breath test. This finding, however, has been challenged by a number of other studies that found no increased incidence of bacterial overgrowth based on jejunal aspirate culture. Abnormal H2 breath test can occur because of small-bowel rapid transit and may lead to erroneous interpretation. Hence, the role of testing for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in IBS patients remains unclear.

Studies using culture-independent approaches such as 16S rRNA gene-based analysis found significant differences between the molecular profile of the fecal microbiota of IBS patients and that of healthy subjects. IBS patients had decreased proportions of the genera Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus and increased ratios of Firmicutes:Bacteroidetes. It has been speculated that these changes may be related to stress and diet. A temporary reduction in lactobacilli has been reported in animal models of early-life stress. On the other hand, Firmicutes is the dominant phylum in adults consuming a diet high in animal fat and protein. However, it is still unclear whether such changes in fecal microbiota are causal, consequential, or merely the result of constipation and diarrhea. In addition, the stability of the change in the microbiota needs to be determined.

Abnormal Serotonin Pathways The serotonin (5-HT)-containing enterochromaffin cells in the colon are increased in a subset of IBS-D patients compared to healthy individuals or patients with ulcerative colitis. Furthermore, postprandial plasma 5-HT levels were significantly higher in this group of patients compared to healthy controls. Because serotonin plays an important role in the regulation of GI motility and visceral perception, the increased release of serotonin may contribute to the postprandial symptoms of these patients and provides a rationale for the use of serotonin antagonists in the treatment of this disorder.

353 |

Diverticular Disease and Common Anorectal Disorders |

DIVERTICULAR DISEASE

![]() Incidence and Epidemiology In the United States, diverticulosis affects 70% of the population above the age of 80. Fortunately, only 20% of patients with diverticulosis develop symptomatic disease, 1–2% require hospitalization, and <1% will require surgery. Diverticular disease has become the fifth most costly gastrointestinal disorder in the United States. Previously overlooked, the majority of patients with diverticular disease report a lower health-related quality of life and more depression as compared to matched controls, thus adding to health care costs. Formerly, diverticular disease was confined to developed countries; however, with the adoption of westernized diets in underdeveloped countries, diverticulosis is on the rise across the globe. Immigrants to the United States develop diverticular disease at the same rate as U.S. natives. Although the prevalence among females and males is similar, males tend to present at a younger age. The mean age at presentation of the disease is 59 years and is now shifting to affect younger populations.

Incidence and Epidemiology In the United States, diverticulosis affects 70% of the population above the age of 80. Fortunately, only 20% of patients with diverticulosis develop symptomatic disease, 1–2% require hospitalization, and <1% will require surgery. Diverticular disease has become the fifth most costly gastrointestinal disorder in the United States. Previously overlooked, the majority of patients with diverticular disease report a lower health-related quality of life and more depression as compared to matched controls, thus adding to health care costs. Formerly, diverticular disease was confined to developed countries; however, with the adoption of westernized diets in underdeveloped countries, diverticulosis is on the rise across the globe. Immigrants to the United States develop diverticular disease at the same rate as U.S. natives. Although the prevalence among females and males is similar, males tend to present at a younger age. The mean age at presentation of the disease is 59 years and is now shifting to affect younger populations.

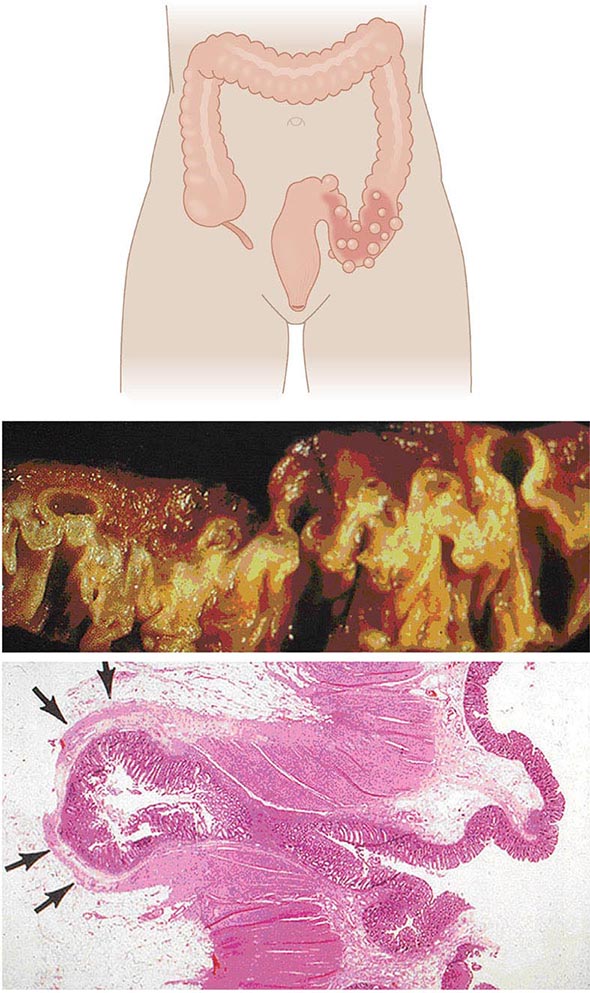

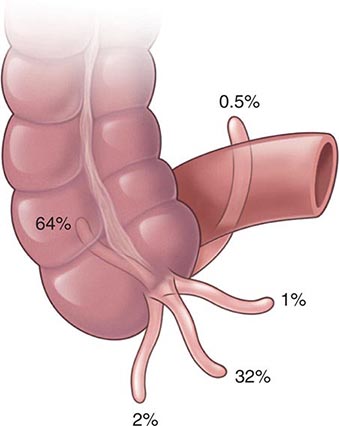

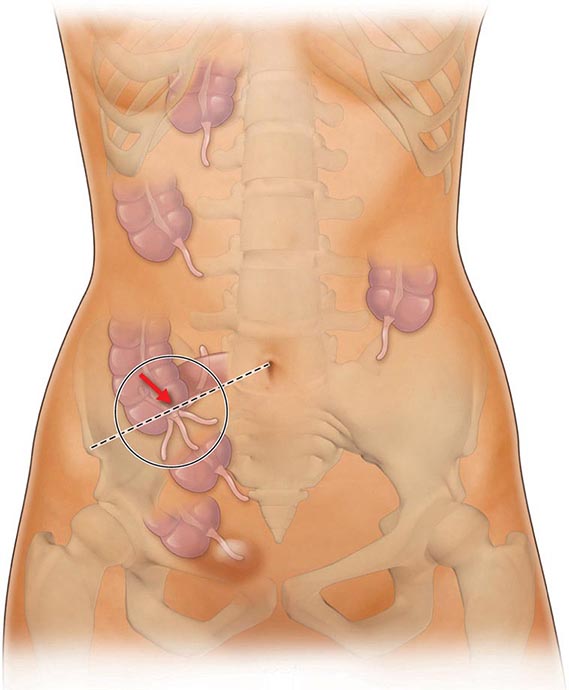

Anatomy and Pathophysiology Two types of diverticula occur in the intestine: true and false (or pseudo diverticula). A true diverticulum is a saclike herniation of the entire bowel wall, whereas a pseudo diverticulum involves only a protrusion of the mucosa and submucosa through the muscularis propria of the colon (Fig. 353-1). The type of diverticulum affecting the colon is the pseudodiverticulum. Diverticula commonly affect the left and sigmoid colon; the rectum is always spared. However, in Asian populations, 70% of diverticula are seen in the right colon and cecum as well. Diverticulitis is inflammation of a diverticulum. Previous understanding of the pathogenesis of diverticulosis attributed a low-fiber diet as the sole culprit, and onset of diverticulitis would occur acutely when these diverticula become obstructed. However, evidence now suggests that the pathogenesis is more complex and multifactorial. The diverticula occur at the point where the nutrient artery, or vasa recti, penetrates through the muscularis propria, resulting in a break in the integrity of the colonic wall. This anatomic restriction may be a result of the relative high-pressure zone within the muscular sigmoid colon. Thus, higher-amplitude contractions combined with constipated, high-fat-content stool within the sigmoid lumen in an area of weakness in the colonic wall results in the creation of these diverticula. Consequently, the vasa recti is either compressed or eroded, leading to either perforation or bleeding. Chronic low-grade inflammation is thought to play a key role. Furthermore, better understanding of the gut microbiota suggests that dysbiosis is an important aspect of disease.

FIGURE 353-1 Gross and microscopic view of sigmoid diverticular disease. Arrows mark an inflamed diverticulum with the diverticular wall made up only of mucosa.

Presentation, Evaluation, and Management of Diverticular Bleeding Hemorrhage from a colonic diverticulum is the most common cause of hematochezia in patients >60 years, yet only 20% of patients with diverticulosis will have gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients at increased risk for bleeding tend to be hypertensive, have atherosclerosis, and regularly use aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Most bleeds are self-limited and stop spontaneously with bowel rest. The lifetime risk of rebleeding is 25%.

Initial localization of diverticular bleeding may include colonoscopy, multiplanar computed tomography (CT) angiogram, or nuclear medicine tagged red cell scan. If the patient is stable, ongoing bleeding is best managed by angiography. If mesenteric angiography can localize the bleeding site, the vessel can be occluded successfully with a coil in 80% of cases. The patient can then be followed closely with repetitive colonoscopy, if necessary, looking for evidence of colonic ischemia. Alternatively, a segmental resection of the colon can be undertaken to eliminate the risk of further bleeding. This may be advantageous in patients on chronic anticoagulation. However, with highly selective coil embolization, the rate of colonic ischemia is <10% and the risk of acute rebleeding is <25%. Long-term results (40 months) indicate that more than 50% of patients with acute diverticular bleeds treated with highly selective angiography have had definitive treatment. As another alternative, a selective infusion of vasopressin can be given to stop the hemorrhage, although this has been associated with significant complications, including myocardial infarction and intestinal ischemia. Furthermore, bleeding recurs in 50% of patients once the infusion is stopped.

If the patient is unstable or has had a 6-unit bleed within 24 h, current recommendations are that surgery should be performed. If the bleeding has been localized, a segmental resection can be performed. If the site of bleeding has not been definitively identified, a subtotal colectomy may be required. In patients without severe comorbidities, surgical resection can be performed with a primary anastomosis. A higher anastomotic leak rate has been reported in patients who received >10 units of blood.

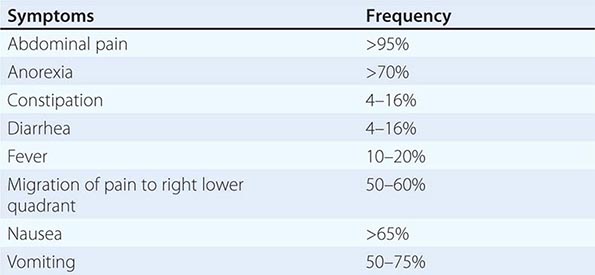

Presentation, Evaluation, and Staging of Diverticulitis Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis characteristically presents with fever, anorexia, left lower quadrant abdominal pain, and obstipation (Table 353-1). In <25% of cases, patients may present with generalized peritonitis indicating the presence of a diverticular perforation. If a pericolonic abscess has formed, the patient may have abdominal distention and signs of localized peritonitis. Laboratory investigations will demonstrate a leukocytosis. Rarely, a patient may present with an air-fluid level in the left lower quadrant on plain abdominal film. This is a giant diverticulum of the sigmoid colon and is managed with resection to avoid impending perforation.

|

PRESENTATION OF DIVERTICULAR DISEASE |

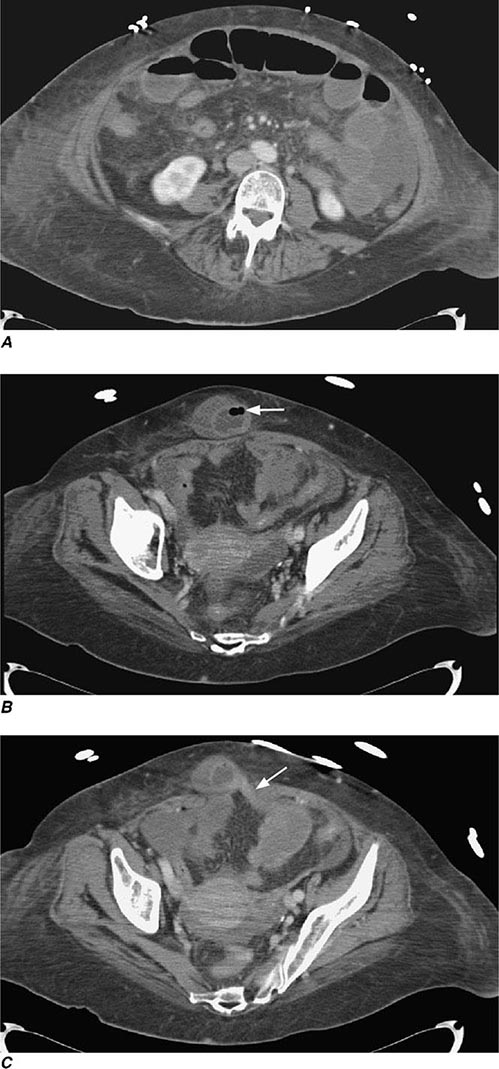

The diagnosis of diverticulitis is best made on CT with the following findings: sigmoid diverticula, thickened colonic wall >4 mm, and inflammation within the periodic fat ± the collection of contrast material or fluid. In 16% of patients, an abdominal abscess may be present. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (Chap. 352) may mimic those of diverticulitis. Therefore, suspected diverticulitis that does not meet CT criteria or is not associated with a leukocytosis or fever is not diverticular disease. Other conditions that can mimic diverticular disease include an ovarian cyst, endometriosis, acute appendicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.

Although the benefit of colonoscopy in the evaluation of patients with diverticular disease has been called into question, its use is still considered important in the exclusion of colorectal cancer. The parallel epidemiology of colorectal cancer and diverticular disease provides enough concern for an endoscopic evaluation before operative management. Therefore, a colonoscopy should be performed ~6 weeks after an attack of diverticular disease.

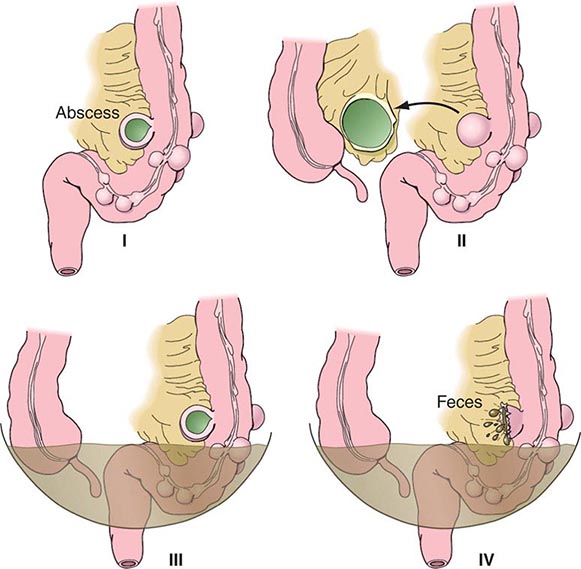

Complicated diverticular disease is defined as diverticular disease associated with an abscess or perforation and less commonly with a fistula (Table 353-1). Perforated diverticular disease is staged using the Hinchey classification system (Fig. 353-2). This staging system was developed to predict outcomes following the surgical management of complicated diverticular disease. In complicated diverticular disease with fistula formation, common locations include cutaneous, vaginal, or vesicle fistulas. These conditions present with either passage of stool through the skin or vagina or the presence of air in the urinary stream (pneumaturia). Colovaginal fistulas are more common in women who have undergone a hysterectomy.

FIGURE 353-2 Hinchey classification of diverticulitis. Stage I: Perforated diverticulitis with a confined paracolic abscess. Stage II: Perforated diverticulitis that has closed spontaneously with distant abscess formation. Stage III: Noncommunicating perforated diverticulitis with fecal peritonitis (the diverticular neck is closed off, and therefore, contrast will not freely expel on radiographic images). Stage IV: Perforation and free communication with the peritoneum, resulting in fecal peritonitis.

Recurrent Symptoms Recurrent abdominal symptoms following surgical resection for diverticular disease occur in 10% of patients. Recurrent diverticular disease develops in patients following inadequate surgical resection. A retained segment of diseased rectosigmoid colon is associated with twice the incidence of recurrence. The presence of irritable bowel syndrome may also cause recurrence of initial symptoms. Patients undergoing surgical resection for presumed diverticulitis and symptoms of chronic abdominal cramping and irregular loose bowel movements consistent with irritable bowel syndrome have poorer functional outcomes.

COMMON DISEASES OF THE ANORECTUM

RECTAL PROLAPSE (PROCIDENTIA)

Incidence and Epidemiology Rectal prolapse is six times more common in women than in men. The incidence of rectal prolapse peaks in women >60 years. Women with rectal prolapse have a higher incidence of associated pelvic floor disorders including urinary incontinence, rectocele, cystocele, and enterocele. About 20% of children with rectal prolapse will have cystic fibrosis. All children presenting with prolapse should undergo a sweat chloride test. Less common associations include Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, congenital hypothyroidism, Hirschsprung’s disease, dementia, mental retardation, and schizophrenia.

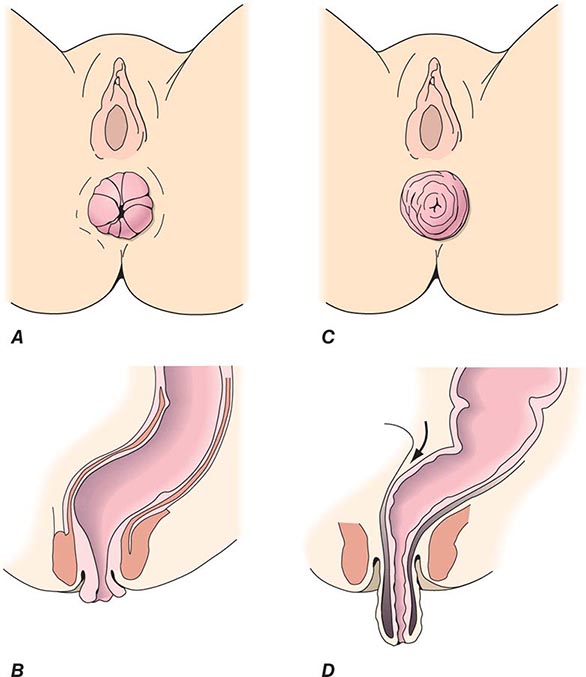

Anatomy and Pathophysiology Rectal prolapse (procidentia) is a circumferential, full-thickness protrusion of the rectal wall through the anal orifice. It is often associated with a redundant sigmoid colon, pelvic laxity, and a deep rectovaginal septum (pouch of Douglas). Initially, rectal prolapse was felt to be the result of early internal rectal intussusception, which occurs in the upper to mid rectum. This was considered to be the first step in an inevitable progression to full-thickness external prolapse. However, only 1 of 38 patients with internal prolapse followed for >5 years developed full-thickness prolapse. Others have suggested that full-thickness prolapse is the result of damage to the nerve supply to the pelvic floor muscles or pudendal nerves from repeated stretching with straining to defecate. Damage to the pudendal nerves would weaken the pelvic floor muscles, including the external anal sphincter muscles. Bilateral pudendal nerve injury is more significantly associated with prolapse and incontinence than unilateral injury.

Presentation and Evaluation In external prolapse, the majority of patient complaints include anal mass, bleeding per rectum, and poor perianal hygiene. Prolapse of the rectum usually occurs following defecation and will spontaneously reduce or require the patient to manually reduce the prolapse. Constipation occurs in ~30–67% of patients with rectal prolapse. Differing degrees of fecal incontinence occur in 50–70% of patients. Patients with internal rectal prolapse will present with symptoms of both constipation and incontinence. Other associated findings include outlet obstruction (anismus) in 30%, colonic inertia in 10%, and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in 12%.

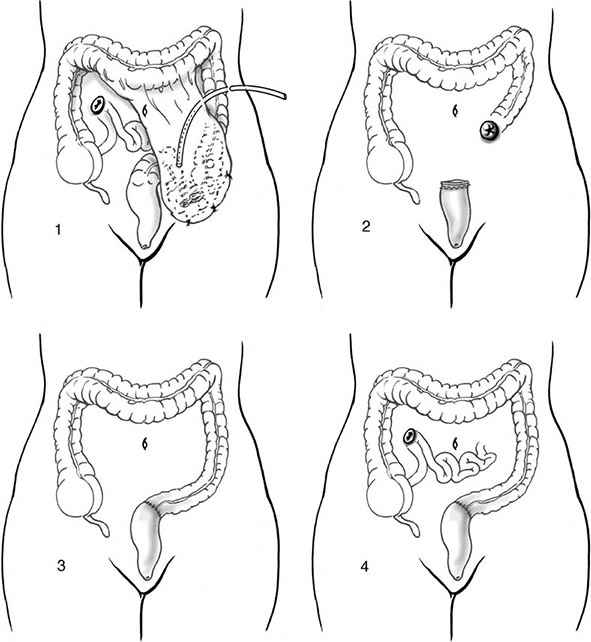

Office evaluation is best performed after the patient has been given an enema, which enables the prolapse to protrude. An important distinction should be made between full-thickness rectal prolapse and isolated mucosal prolapse associated with hemorrhoidal disease (Fig. 353-4). Mucosal prolapse is known for radial grooves rather than circumferential folds around the anus and is due to increased laxity of the connective tissue between the submucosa and underlying muscle of the anal canal. The evaluation of prolapse should also include cystoproctography and colonoscopy. These examinations evaluate for associated pelvic floor disorders and rule out a malignancy or a polyp as the lead point for prolapse. If rectal prolapse is associated with chronic constipation, the patient should undergo a defecating proctogram and a sitzmark study. This will evaluate for the presence of anismus or colonic inertia. Anismus is the result of attempting to defecate against a closed pelvic floor and is also known as nonrelaxing puborectalis. This can be seen when straightening of the rectum fails to occur on fluoroscopy while the patient is attempting to defecate. In colonic inertia, a sitzmark study will demonstrate retention of >20% of markers on abdominal x-ray 5 days after swallowing. For patients with fecal incontinence, endoanal ultrasound and manometric evaluation, including pudendal nerve testing of their anal sphincter muscles, may be performed before surgery for prolapse (see “Fecal Incontinence,” below).

FIGURE 353-4 Degrees of rectal prolapse. Mucosal prolapse only (A, B, sagittal view). Full-thickness prolapse associated with redundant rectosigmoid and deep pouch of Douglas (C, D, sagittal view).

FECAL INCONTINENCE

Incidence and Epidemiology Fecal incontinence is the involuntary passage of fecal material for at least 1 month in an individual with a developmental age of at least 4 years. The prevalence of fecal incontinence in the United States is 0.5–11%. The majority of patients are women and above the age of 65. A higher incidence of incontinence is seen among parous women. One-half of patients with fecal incontinence also suffer from urinary incontinence. The majority of incontinence is a result of obstetric injury to the pelvic floor, either while carrying a fetus or during the delivery. An anatomic sphincter defect may occur in up to 32% of women following childbirth regardless of visible damage to the perineum. Risk factors at the time of delivery include prolonged labor, the use of forceps, and the need for an episiotomy. Symptoms of incontinence can present after two or more decades following obstetric injury. Medical conditions known to contribute to the development of fecal incontinence are listed in Table 353-4.

|

MEDICAL CONDITIONS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO SYMPTOMS OF FECAL INCONTINENCE |

Anatomy and Pathophysiology The anal sphincter complex is made up of the internal and external anal sphincter. The internal sphincter is smooth muscle and a continuation of the circular fibers of the rectal wall. It is innervated by the intestinal myenteric plexus and is therefore not under voluntary control. The external anal sphincter is formed in continuation with the levator ani muscles and is under voluntary control. The pudendal nerve supplies motor innervation to the external anal sphincter. Obstetric injury may result in tearing of the muscle fibers anteriorly at the time of the delivery. This results in an obvious anterior defect on endoanal ultrasound. Injury may also be the result of stretching of the pudendal nerves during pregnancy or delivery of the fetus through the birth canal.

Presentation and Evaluation Patients may suffer with varying degrees of fecal incontinence. Minor incontinence includes incontinence to flatus and occasional seepage of liquid stool. Major incontinence is frequent inability to control solid waste. As a result of fecal incontinence, patients suffer from poor perianal hygiene. Beyond the immediate problems associated with fecal incontinence, these patients are often withdrawn and suffer from depression. For this reason, quality-of-life measures are an important component in the evaluation of patients with fecal incontinence.

The evaluation of fecal incontinence should include a thorough history and physical exam including digital rectal examination (DRE). Weak sphincter tone on DRE and loss of the “anal wink” reflex (S1-level control) may indicate a neurogenic dysfunction. Perianal scars may represent surgical injury. Other studies helpful in the diagnosis of fecal incontinence include anal manometry, pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML), and endoanal ultrasound. Centers that care for patients with fecal incontinence will have an anorectal physiology laboratory that uses standardized methods of evaluating anorectal physiology. Anorectal manometry (ARM) measures resting and squeeze pressures within the anal canal using an intraluminal water-perfused catheter. Current methods of ARM include use of a three-dimensional, high-resolution system with a 12-catheter perfusion system, which allows physiologic delineation of anatomic abnormalities. Pudendal nerve studies evaluate the function of the nerves innervating the anal canal using a finger electrode placed in the anal canal. Stretch injuries to these nerves will result in a delayed response of the sphincter muscle to a stimulus, indicating a prolonged latency. Finally, endoanal ultrasound will evaluate the extent of the injury to the sphincter muscles before surgical repair. Unfortunately, all of these investigations are user-dependent, and very few studies demonstrate that these studies predict outcome following an intervention. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used, but its routine use for imaging in fecal incontinence is not well established.

Rarely does a pelvic floor disorder exist alone. The majority of patients with fecal incontinence will have some degree of urinary incontinence. Similarly, fecal incontinence is a part of the spectrum of pelvic organ prolapse. For this reason, patients may present with symptoms of obstructed defecation as well as fecal incontinence. Careful evaluation including dynamic MRI or cinedefecography should be performed to search for other associated defects. Surgical repair of incontinence without attention to other associated defects may decrease the success of the repair.

HEMORRHOIDAL DISEASE

Incidence and Epidemiology Symptomatic hemorrhoids affect >1 million individuals in the Western world per year. The prevalence of hemorrhoidal disease is not selective for age or sex. However, age is known to be a risk factor. The prevalence of hemorrhoidal disease is less in underdeveloped countries. The typical low-fiber, high-fat Western diet is associated with constipation and straining and the development of symptomatic hemorrhoids.

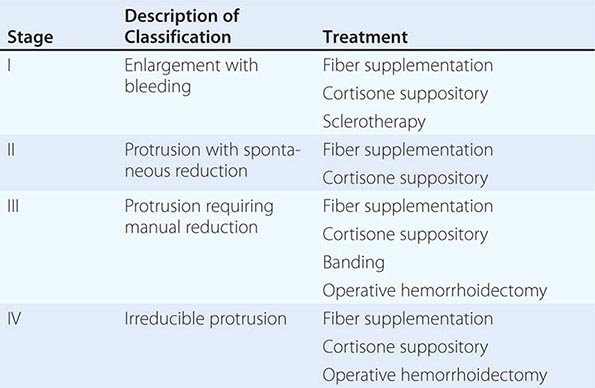

Anatomy and Pathophysiology Hemorrhoidal cushions are a normal part of the anal canal. The vascular structures contained within this tissue aid in continence by preventing damage to the sphincter muscle. Three main hemorrhoidal complexes traverse the anal canal—the left lateral, the right anterior, and the right posterior. Engorgement and straining lead to prolapse of this tissue into the anal canal. Over time, the anatomic support system of the hemorrhoidal complex weakens, exposing this tissue to the outside of the anal canal where it is susceptible to injury. Hemorrhoids are commonly classified as external or internal. External hemorrhoids originate below the dentate line and are covered with squamous epithelium and are associated with an internal component. External hemorrhoids are painful when thrombosed. Internal hemorrhoids originate above the dentate line and are covered with mucosa and transitional zone epithelium and represent majority of hemorrhoids. The standard classification of hemorrhoidal disease is based on the progression of the disease from their normal internal location to the prolapsing external position (Table 353-5).

|

THE STAGING AND TREATMENT OF HEMORRHOIDS |

Presentation and Evaluation Patients commonly present to a physician for two reasons: bleeding and protrusion. Pain is less common than with fissures and, if present, is described as a dull ache from engorgement of the hemorrhoidal tissue. Severe pain may indicate a thrombosed hemorrhoid. Hemorrhoidal bleeding is described as painless bright red blood seen either in the toilet or upon wiping. Occasional patients can present with significant bleeding, which may be a cause of anemia; however, the presence of a colonic neoplasm must be ruled out in anemic patients. Patients who present with a protruding mass complain about inability to maintain perianal hygiene and are often concerned about the presence of a malignancy.

The diagnosis of hemorrhoidal disease is made on physical examination. Inspection of the perianal region for evidence of thrombosis or excoriation is performed, followed by a careful digital examination. Anoscopy is performed paying particular attention to the known position of hemorrhoidal disease. The patient is asked to strain. If this is difficult for the patient, the maneuver can be performed while sitting on a toilet. The physician is notified when the tissue prolapses. It is important to differentiate the circumferential appearance of a full-thickness rectal prolapse from the radial nature of prolapsing hemorrhoids (see “Rectal Prolapse,” above). The stage and location of the hemorrhoidal complexes are defined.

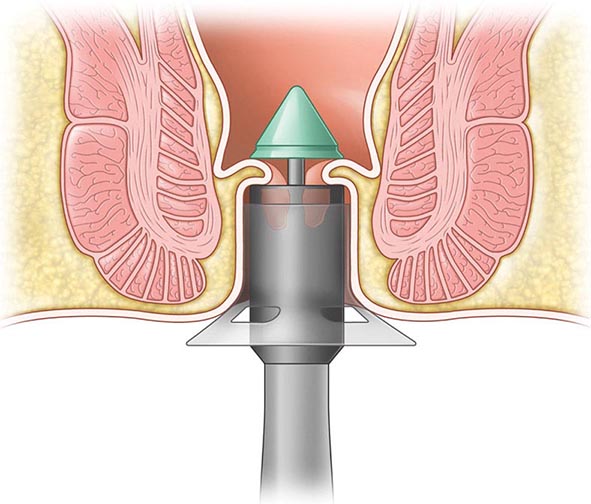

ANORECTAL ABSCESS