83 Menstrual Disorders

Eitology and Pathogenesis

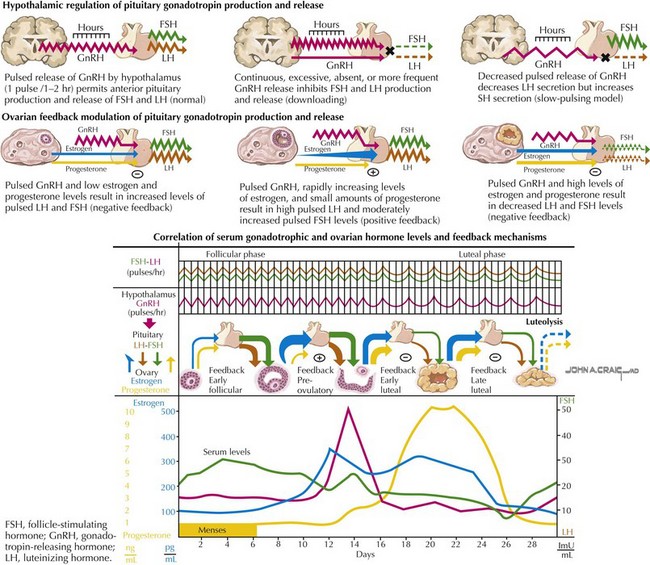

Anovulatory cycles result when the increase in estrogen during the follicular stage does not result in a surge of LH and therefore ovulation cannot occur. Because the endometrium is mainly exposed to estrogen without progesterone, it can become highly thickened, resulting in heavy, prolonged, or unsynchronized sloughing of the lining (Figure 83-1).

Differential Diagnosis

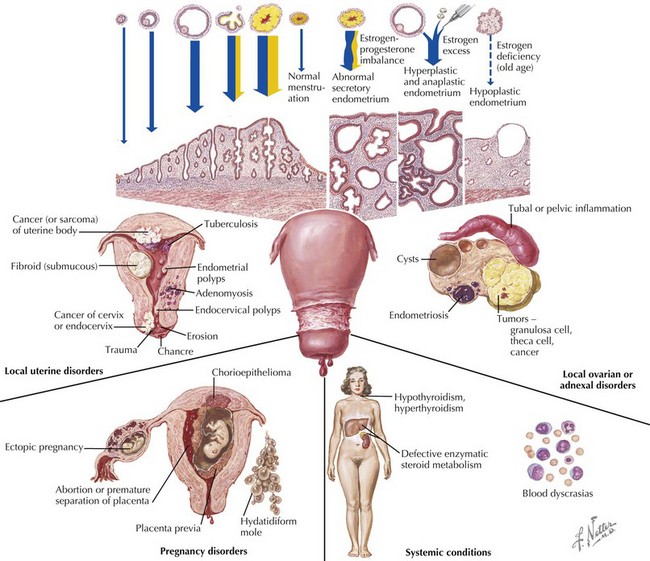

Trauma to the vagina or cervix, retained foreign body, and vascular or anatomic lesions must be included in the differential diagnosis. Congenital anatomic abnormalities may be considered when the patient reports having regular, red-colored menstrual bleeding followed by brown or prune-colored discharge between cycles. This is caused by the normal uterus emptying in a cyclic pattern while the obstructed uterus or vagina empties into a fistula slowly over a period of time. A foul smell may accompany this intermenstrual discharge because of infection with anaerobic bacteria (Figure 83-2).

El-Hemaidi I, Gharaibeh A, Shehata H. Menorrhagia and bleeding disorders. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19(6):513-520.

Emans SJ. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. In: Emans SJ, Laufer MR, Goldstein DP, editors. Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. ed 5. Philadelphia, Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2005:270-286.

Lavin C. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding in adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1996;8(4):328-332.

Lazovic G, Radivojec U, Milicevic S, et al. The most frequent hormone dysfunctions in juvenile bleeding. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2007;52(1):35-40.

Messinis IE. From menarche to regular menstruation: endocrinological background. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1092:49-56.

Rimza ME. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Pediatr Rev. 2002;23:227-232.

Toth M, Patton DL, Esquenazi B, et al. Association between Chlamydia trachomatis and abnormal bleeding. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;57(5):361-366.