45 Menstrual cycle disorders

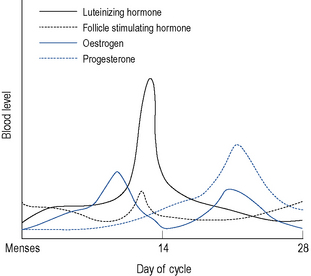

Menstruation itself occurs as a result of cyclic hormonal variations (Fig. 45.1). During the first half or follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, the endometrium thickens under the influence of increasing levels of oestrogen (most notably estradiol, which at the peak of its preovulatory surge reaches around 2000 pmol/L) secreted from the developing ovarian follicles. Once the serum oestrogen level has surpassed a critical point it triggers, by positive feedback, the anterior pituitary to release, about 24 h later, a surge of luteinising hormone (LH; up to 50 iu/L) and after 30–36 h, ovulation follows.

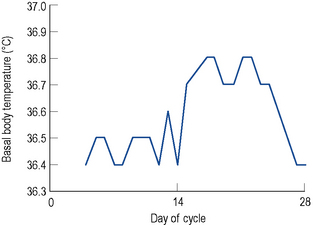

After ovulation, which occurs around day 14 of a 28-day menstrual cycle, and as the luteal phase progresses, the endometrium begins to respond to increasing levels of progesterone. Both progesterone and oestrogen are secreted from the corpus luteum which is formed from the remains of the ovarian follicle after ovulation. The lifespan of the corpus luteum is remarkably constant and lasts between 12 and 14 days; hence, the length of the second half or the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle is between 12 and 14 days. Between days 18 and 22 of a 28-day cycle, both sex steroids peak, with levels of progesterone reaching around 30 nmol/L. As progesterone has a thermogenic effect upon the hypothalamus, basal body temperature increases by about 1 °C in the second half of an ovulatory cycle (Fig. 45.2). Most ovulatory cycles range from 21 to 34 days.

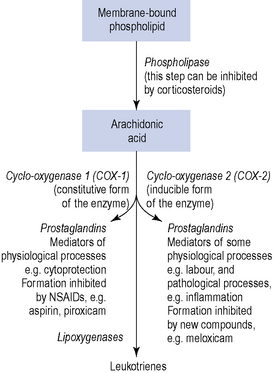

There is evidence which suggests a physiological and pathological role for the local hormones, known as prostaglandins, in the process of menstruation. Prostaglandins are 20-carbon oxygenated, polyunsaturated bioactive lipids, which are cyclo-oxygenase-derived products of arachidonic acid. Indeed, both the myometrium and the endometrium are capable of synthesising and responding to prostaglandins. A potential role for another family of autocoids, the leukotrienes, in the regulation of uterine function remains uncertain, although it is known that leukotrienes can also be synthesised from arachidonic acid by lipoxygenase enzymes (Fig. 45.3).

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS)

PMS encompasses both mood changes and physical symptoms. Symptoms may start up to 14 days before menstruation, although more usually they begin just a few days before and disappear at the onset of, or shortly after, menstruation. However, for some women, the beginning of menstruation may not signal the complete resolution of symptoms. Numerous studies have demonstrated that this condition can cause substantial impairment of normal daily activity, including reduced occupational activity and significant levels of work absenteeism. Severity varies from cycle to cycle and may be influenced by other life factors such as stress and tiredness. The most severe form of PMS may be referred to as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) as defined by the Modified Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders appendix IV, or DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and for which the criteria are set out in Box 45.1. Other bodies (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2000) have published diagnostic criteria for PMS (Box 45.2). There is considerable overlap between PMS and PMDD.

Box 45.1 Summary of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD)

Seriously interferes with work, social activities, relationships

Not an exacerbation of another disorder

Confirmed by prospective daily ratings during at least two consecutive symptomatic cycles

Box 45.2 Diagnostic criteria for premenstrual syndrome (PMS)

| Affective | Somatic |

|---|---|

| Depression | Breast tenderness |

| Angry outbursts | Abdominal bloating |

| Irritability | Headache |

| Anxiety | Swelling of extremities |

| Confusion | |

| Social withdrawal |

Symptoms relieved within 4 days of menses onset without recurrence until at least cycle day 13

Symptoms occur reproducibly during two cycles of prospective recording

Patient suffers from identifiable dysfunction in social or economic performance

Aetiology

Vitamins and minerals

Pyridoxine phosphate is a co-factor in a number of enzyme reactions, particularly those leading to production of dopamine and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine). It has been suggested that disturbances of the oestrogen/progesterone balance could cause a relative deficiency of pyridoxine, and supplementation with this vitamin appears to ease the depression sometimes associated with the oral contraceptive pill. Decreased dopamine levels would tend to increase serum prolactin, and decreased serotonin levels could be a factor in emotional disturbances, particularly depression. There is some evidence that premenstrual mood changes are linked to cycle-related alterations in serotonergic activity within the CNS and, therefore, serotonin may be important in the pathogenesis of PMS. There are also data to suggest that a variety of nutrients may play a role in the aetiology of PMS, specifically calcium and vitamin D. Further hydroxylation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) takes place in target tissues which include the breast and the endometrium. In the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII), high total vitamin D intake lowered risk of PMS by almost a third (Bertone-Johnson et al., 2005). Oestrogen influences calcium metabolism by affecting intestinal absorption, and parathyroid gene expression and secretion, so triggering fluctuations throughout the menstrual cycle. Disruption of calcium homeostasis has been associated with affective disorders.

Symptoms

Symptoms occur 1–14 days before menstruation begins and disappear at the onset or shortly after menstruation begins. For the rest of the cycle, the woman feels well. Symptoms are cyclical, although they may not be experienced every cycle, and can be either physical and/or psychological (see Boxes 45.1. and 45.2 for symptomatology). The lives of the 5% or so of women who are severely affected may be completely disrupted in the second half of the menstrual cycle. The symptoms of PMS tend to decrease as a woman gets closer to the menopause as her ovulatory cycles become less frequent.

Management

Pharmacological management

Combined oral contraceptives (COC)

It is thought that use of third-generation progestogens is associated with increased resistance to the anticoagulant action of activated protein C. Oral contraceptive treatment diminishes the efficacy with which activated protein C down regulates in vitro thrombin formation. This is known as activated protein C resistance and is more pronounced in women using the COC pills containing desogestrel than in women using those containing levonorgestrel. However, it has also been recognised that women who do react to third-generation progestogens with venous thromboembolism may be revealing a latent thrombophilia. There are several conditions, congenital or acquired, that can cause thrombophilic alterations. A genetic factor known as factor V Leiden mutation is the most common inherited cause of thrombophilia, and this mutation results in resistance to the effects of activated protein C. Carriers of this mutation have more than a 30-fold increase in risk of thrombotic complications during oral contraceptive use, although this has been disputed (Farmer et al., 2000) because no increase in risk of venous thromboembolism was found with the third-generation progestogens. In conclusion, if there is a history of thromboembolic disease at a young age in the immediate family, then disturbances of the coagulation system must be ruled out.

Bromocriptine

Bromocriptine stimulates central dopamine receptors and thus inhibits the release of prolactin. It may be useful for breast tenderness and occasionally has beneficial effects upon fluid retention and mood changes. It should be used in small doses, for example, 1–1.25 mg at bedtime with food, to avoid the side effects of nausea and faintness due to hypotension. The dose can be slowly increased to 2.5 mg twice a day if required. It is advised that ergot-derived dopamine receptor agonists, such as bromocriptine, have been associated with pulmonary, retroperitoneal and pericardial fibrotic reactions (Anon, 2002). Excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden onset of sleep can also occur with dopaminergic drugs.

Antidepressants

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are becoming more popular in the treatment of PMS-related depression because they are effective and well tolerated (Brown et al., 2009). Several randomised controlled trials using fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, fluvoxamine or paroxetine concluded that SSRIs are an effective first-line therapy for severe PMS and the side effects at low doses are generally acceptable. Two studies also found that not only do SSRIs improve behavioural symptoms, but some improvement in physical symptoms was also noted. Common side effects experienced include headache, nervousness, drowsiness and fatigue, sexual dysfunction and gastro-intestinal disturbances. Other agents such as tricyclic antidepressants and anxiolytics such as buspirone have been used. However, they appear to improve fewer PMS symptoms than the SSRIs.

St John’s Wort has been used to reduce the severity of PMS, but the available evidence is limited.

Dysmenorrhoea

Primary dysmenorrhoea

Aetiology and symptoms

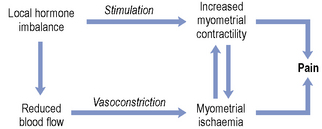

In terms of aetiology, studies carried out in the 1950s and 1960s first drew attention to the possible role of the prostaglandins. This was followed by many in vivo studies which showed that women suffering from primary dysmenorrhoea do have greater concentrations of prostaglandins, predominantly PGF2α, and to some extent PGE2, in their menstrual fluid compared with matched control subjects. Such a prostaglandin imbalance would favour increased myometrial contractility. The effects of the prostaglandins on human myometrium are now well documented, and increased biosynthesis of prostaglandins may also account for the gastro-intestinal problems encountered by some sufferers. A role for the prostaglandins is substantiated by the fact that women whose diet contains more omega-3 fatty acids tend to suffer less. When eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) is the substrate for prostaglandin biosynthesis, prostaglandins of the three series are produced (e.g. PGE3 and TXA3). Such local hormones are less potent stimulators of the myometrium and less effective vasoconstrictors. Other potential mediators are the endothelins, vasoactive peptides produced in the endometrium that may play a role in the local regulation of prostaglandin synthesis, and vasopressin, a posterior pituitary hormone that stimulates uterine activity and decreases uterine blood flow. The smaller branches of the uterine arteries are very sensitive to the vasoconstrictor actions of these mediators, and it is these resistance vessels that are important in the control of uterine blood flow. The interrelationship between blood flow and myometrial activity is summarised in Fig. 45.4.

Treatment

In terms of analgesia, the most rational choice would be a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) (Zahradnik et al., 2010), as these compounds decrease prostaglandin biosynthesis by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase. Differences in anti-inflammatory activity between different NSAIDs are small. However, there is considerable variation in individual patient tolerance and response, and a lack of response to one particular agent does not mean that a patient would not respond to a different NSAID.

Mefenamic acid is frequently used to manage pain due to dysmenorrhoea. As previously stated, this compound not only inhibits prostaglandin production but also appears to possess some prostaglandin E receptor blocking activity which may serve to augment its effect. However, these preparations are not suitable for all women and some, about 30% of women, will not respond. There is substantive evidence (Marjoribanks et al., 2010) that NSAIDs are effective in the treatment of dysmenorrhoea and are more effective than paracetamol. However, there is insufficient evidence regarding the comparative efficacy of individual agents in terms of superiority of analgesia or side-effect profile.

A small study has investigated the use of the leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast (Singulair®) in the treatment of dysmenorrhoea (Fujiwara et al., 2010). The results suggest blockade of leukotriene receptors alleviate pain and reduce NSAID usage, and this appears to be most effective in women without endometriosis.

It has been estimated that approximately 50% of primary dysmenorrhoea sufferers will gain relief from taking the oral contraceptive pill, although, as this is a condition afflicting young girls, there may be attitudinal problems to the use of these products either in the patient or her parents. The oral contraceptive pill inhibits ovulation and thereby prevents increased luteal phase prostaglandin synthesis and so decreases uterine contractility. However, not all women are suitable candidates for COC use because of the potential problems associated with exogenous oestrogen. Contraindications include high blood pressure, obesity and a significant personal or family history of venous thromboembolism. Progestogenic preparations (e.g. dydrogesterone 10 mg twice daily from day 5 to 25 of cycle, norethisterone 5 mg three times daily from day 5 to 24 of the cycle) or progestogen-only pills may be useful if they inhibit ovulation. For pain relief, there appears to be no significant difference between the various formulations. Antispasmodics such as hyoscine butylbromide and propantheline bromide have a very limited role in the treatment of dysmenorrhoea, not least because of their poor oral bioavailability. Related compounds such as atropine also have negligible effects upon the human uterus. A summary of the treatment options for dysmenorrhoea is presented in Table 45.1. Future therapy may involve use of vasopressin antagonists. Clinical trials have shown these compounds to be effective and well tolerated and they do not affect bleeding patterns.

| Drug | Side effects |

|---|---|

| NSAIDs | Gastric irritation, which can be minimised by taking with or after food or selecting an agent with less gastrotoxicity, for example, ibuprofen. Hypersensitivity reactions, particularly bronchospasm. Headache, dizziness, vertigo, hearing problems (e.g. tinnitus) and haematuria. NSAIDs may adversely affect renal function and provoke acute renal failure |

| Combined oral contraceptives | Many side effects are dose related and so the development of the ultra-low-dose preparations (i.e. those containing 20 μcg ethinylestradiol) is beneficial. An alternative to the oral preparations is the low-dose transdermal combined contraceptive which releases 20 μcg ethinylestradiol and 150 μcg of norelgestromin (active metabolite of the third-generation progestogen, norgestimate). The most serious potential adverse effect is the increased risk of thromboembolism due to a decrease in circulating levels of antithrombin III while increasing serum levels of some clotting factors. This risk increases with age and smoking. Analysis of current data suggests that the risk of breast cancer is not increased for most women who use the combined oral contraceptive for the major portion of their reproductive years. Use of the combined oral contraceptive also conveys several health benefits besides being an effective contraceptive. The progestogenic side effects are discussed as follows |

| Progestogen-only preparations | Use of these agents may cause menstrual disturbances, for example, breakthrough bleeding. Other adverse effects relate to the selectivity of the synthetic hormone, for example, norethisterone is a first-generation progestogen and has some affinity for steroid receptors other than progesterone and so possesses androgenic, oestrogenic and antioestrogenic activity. The third-generation progestogens (gestodene, norgestimate and desogestrel) have the least androgenic activity. This should be advantageous as it is the androgenicity of the compounds that correlates with the decrease in high-density lipoproteins |

Non-pharmacological management options have recently been reviewed and include high-frequency transcutaneous nerve stimulation (TENS) and acupuncture (Proctor et al., 2002). Both of these therapies showed some potential benefit. There is limited evidence to support the use of uterine nerve ablation and presacral neurectomy, to interrupt the sensory nerve fibres near the cervix blocking the pain pathway. Dietary therapies such as vitamin and mineral supplementation have also been investigated. One study identified that vitamin B1 100 mg daily may be effective in relieving pain (Proctor et al., 2002). Magnesium supplementation also shows promising results. Unfortunately, evidence is still lacking to support use of other herbal and dietary therapies, for example, omega-3 fatty acids. Some Chinese herbal medicines have shown interesting results but trial quality is poor.

Menorrhagia

Aetiology and investigation

The aetiology of menorrhagia can be divided into three categories: underlying pelvic pathology, systemic disease and dysfunctional uterine bleeding (Box 45.3). The typical symptoms suggestive of underlying pelvic pathology are presented in Box 45.4. Pelvic pathologies associated with menorrhagia include myomas (fibroids, common benign tumours of the myometrium), endometriosis, adenomyosis (penetration of endometrial tissue into the myometrium), endometrial polyps, polycystic ovarian disease and endometrial carcinoma. Although endometrial cancer is more typically seen in postmenopausal women, approximately 50% of those patients diagnosed with it premenopausally will have associated menorrhagia. Systemic diseases from which menorrhagia may stem include hypothyroidism, disorders involving the coagulation system such as elevated endometrial levels of plasminogen activator and systemic lupus erythematosus. Very few women fall into this group. About 60% of menorrhagia sufferers have no underlying systemic or pelvic pathology and have ovulatory cycles. These patients are said to have dysfunctional uterine bleeding and local uterine mechanisms appear to be important in the control of menstrual blood loss. Occasionally, cycles may be anovulatory, with heavy blood loss because the endometrium has become hyperplastic under the influence of oestrogen. In addition, use of an intrauterine contraceptive device may also increase menstrual blood loss.

Box 45.3 Causes of menorrhagia (percentage frequency)

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding (60%), that is cause is unknown

Treatment

The management of menorrhagia depends upon the cause of the condition and a woman’s desire to conceive. Treatment can be either surgical or medical (Table 45.2). The effectiveness of drug therapy is obviously influenced by the accuracy of the diagnosis. Drug treatment is also influenced by a woman’s contraceptive needs; for example, COCs can reduce menstrual blood loss by up to 50%, but in women over 35 years of age who smoke, this form of therapy would need careful consideration. Low-dose luteal phase progestogens are no longer recommended for treatment of heavy but regular periods as they increase menstrual blood loss in this situation. However, they may be of value in women with an irregular cycle. Long-term, long-acting progestogens, however, may render a woman amenorrhoeic. Other hormonally based therapies include the GnRH analogues, although their propensity to induce a hypo-oestrogenic state with long-term use may be problematic (a 6-month course would reduce trabecular bone density by 5–6%). Danazol can reduce menstrual blood loss but its use is generally prohibited by its side-effect profile. However, in 2009, a local vaginal treatment of 200 mg a day was investigated in 55 women (Luisi et al., 2009). Results showed danazol to be effective in reducing blood loss and few adverse effects were reported. A trial of ormeloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (similar to raloxifene), 60 mg twice weekly has been used successfully to reduce blood loss with relatively few side effects (Kriplani et al., 2009).

Table 45.2 Summary of drug treatment options for menorrhagia

| Drug | Comments |

|---|---|

| Combined oral contraceptive | See Table 45.1. These preparations are taken for 21 days with a 7-day pill-free (or placebo) period to allow for a withdrawal bleed |

| Progestogen-only preparations | See Table 45.1. Compounds such as norethisterone can be used, for example, 5 mg three times daily or 10 mg twice daily for the latter half of the cycle. Ten days of therapy should be sufficient from day 15 of the cycle in ovulatory cycles. However, if the cycles are anovulatory, then a minimum of 12 days’ therapy is more appropriate. Progestogens for 12 days are also required to prevent endometrial hyperplasia in peri- and postmenopausal women taking oestrogen. When progestogens such as norethisterone are used, the dosage required is higher than that used in the combined oral contraceptive pill, and the adverse effects associated with the synthetic progestogens, particularly the 19-nortestosterone derivatives, may be more pronounced |

| Intrauterine progestogen-only contraceptive | The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUS) typically releases 20 μcg of levonorgestrel/24 h. Unlike non-medicated IUCDs, which may increase menstrual blood loss, this device appears to reduce it, as a result of the local endometrial actions of the progestogen. The device also offers contraceptive cover without many of the side effects associated with the non-medicated IUCDs. Progestogen-related side effects should be minimised because of the low dose of levonorgestrel employed. Initially, bleeding patterns may be disrupted, but menstrual blood loss should become lighter within three menstrual cycles |

| Danazol | Danazol suppress the pituitary–ovarian axis. Side effects include amenorrhoea, hot flushes, sweating, changes in libido, vaginitis and emotional lability. Danazol also causes androgenic side effects such as acne, oily skin and hair, hirsutism, oedema, weight gain, voice deepening and decreasing breast size. Danazol has to be taken daily |

| GnRH analogues (gonadorelin) | After an initial period of stimulation, these agents suppress the pituitary–ovarian axis. As result of inducing a hypo-oestrogenic state, these compounds should only be used for 6 months because they may decrease trabecular bone density |

| NSAIDs | These agents only need to be taken for the first 3–4 days of menses |

| Tranexamic acid | This drug appears well tolerated, but can produce dose-related gastro-intestinal disturbances. Patients who may be predisposed to thrombosis are at risk if given antifibrinolytic therapy. This compound is usually only taken for the first 3 days of menses |

IUCDs, intrauterine contraceptive devices; GnRH, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone.

Women with menorrhagia have greater endometrial fibrinolytic activity, hence the use of antifibrinolytic drugs, which are plasminogen activator inhibitors. Tranexamic acid became available for purchase over the counter in UK pharmacies in 2010 as Cyklo-F®. This can be sold to women aged 18–45 years old with a history of regular heavy menstrual bleeding over several consecutive menstrual cycles. Tranexamic acid reduces menstrual blood loss by up to 50% (Lethaby et al., 2000), the recommended dose being 1 g three times daily starting on the first day of menses for up to 4 days. Agents such as tranexamic acid carry a risk of unwanted thrombogenesis, but this does not appear to be translated into practice as increased numbers of deep vein thromboses. This class of drugs decreases menstrual blood loss better than NSAIDs and oral luteal phase progestogen (Lethaby et al., 2005). However, tranexamic acid should be stopped if it has produced no benefit after three cycles.

The levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive devices (also known as intrauterine systems or LNG-IUS) can be left in place for up to 5 years following insertion. They reduce menstrual blood loss by up to 90% after 12 months of use. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system provides relief from dysmenorrhoea, effective contraception and long-term control of menorrhagia. A study showed that the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device was the most cost-effective treatment followed by ablation surgery (Clegg et al., 2007). In addition, other slow-release progestogenic devices such as nesterone implants and vaginal rings also reduce menstrual blood loss and promote amenorrhoea.

Hysterectomy has been the traditional surgical treatment for menorrhagia, with either an abdominal or vaginal approach used (Marjoribanks et al., 2006). Newer alternatives to hysterectomy include endometrial ablation, which can be done by electrosurgical, laser, microwave or thermal techniques. Endometrial ablation is less invasive than hysterectomy, but recurrence of menorrhagia can occur and amenorrhoea cannot be guaranteed. There is evidence that pretreatment with a single dose of a GnRH agonist before the ablation procedure gives a better result. These preparations cause an initial stimulation of gonadotrophin release which then suppresses the hypothalamic–pituitary axis, producing a hypo-oestrogenic state. If circulating levels of oestrogen are low, then endometrial growth will not be stimulated; thus, it will be thinner, making the surgical endometrial destruction more effective. With GnRH pretreatment, modern techniques such as microwave ablation have achieved amenorrhoea rates of about 50% and patient satisfaction rates of 90%.

Endometriosis

Treatment

None of the aforementioned drug therapies are free from side effects. Use of the GnRH analogues may evoke menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes, decreased libido, vaginal dryness (topical vaginal lubricants may be helpful), mood changes and headache. The problems associated with the hypo-oestrogenic state limit the long-term use of GnRH analogues. Although lipoprotein levels are not affected adversely, bone mass is, and this loss of bone density may not be entirely reversible after cessation of therapy. Various ‘add-back’ hormone replacement therapies have been successfully used to minimise bone demineralisation, for example, low-dose oestrogen/progestogen combinations used continuously. Such regimens protect against osteoporosis and other hypo-oestrogenic side effects without apparently affecting clinical efficacy. Pain associated with endometriosis was relieved similarly by gosarelin and a low-dose oral contraceptive (Prentice et al., 1999). However, side-effect profiles differed, for example, hot flushes and vaginal dryness with the former agent and headache and weight gain with the latter.

Case 45.1

Answers

Case 45.2

Answers

Case 45.3

Answers

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Premenstrual Syndrome, ACOG Practice Bulletin No 15. Washington, DC: ACOG. 2000.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.; 2000.

Anon. Fibrotic reactions with pergolide and other ergot-derived dopamine receptor agonists. Curr. Probl. Pharmacovigilance. 2002;23:3.

Bertone-Johnson E.R., Hankinson S.E., Bendich A., et al. Calcium and vitamin D intake and risk of incident premenstrual syndrome. Arch. Intern. Med.. 2005;165:1246-1252.

Brown J., O’Brien P.M.S., Majoribanks J., et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (2):2009. Art No. CD001396 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub2

Clegg J.P., Guest J.F., Hurskainen R. Cost-utility of levonorgestrel intrauterine system compared with hysterectomy and second generation endometrial ablative techniques in managing patients with menorrhagia in the UK. Curr. Med. Res. Opin.. 2007;23:1637-1648.

Farmer R.D.T., Williams T.J., Simpson E.L., et al. Effect of 1995 pill scare on rates of venous thromboembolism among women taking combined oral contraceptives: analysis of General Practice Research Database. Br. Med. J.. 2000;321:477-479.

Fujiwara H., Konno R., Netsu S., et al. Efficacy of montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, for the treatment of dysmenorrhea: a prospective, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Eur. J. Obst. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol.. 2010;148:195-198.

Kriplani A., Kulshrestha V., Agarwal N. Efficacy and safety of ormeloxifene in management of menorrhagia: a pilot study. J. Obst. Gynaecol. Res.. 2009;35:746-752.

Lethaby A., Farquhar C., Cooke I. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (4):2000. Art No. CD000249 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000249

Lethaby A., Cooke I., Rees M.C. Progesterone or progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (4):2005. Art No. CD002126 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002126.pub2

Luisi S., Razzi S., Lazzeri L., et al. Efficacy of vaginal danazol treatment in women with menorrhagia. Fert. Ster.. 2009;92:1351-1354.

Marjoribanks J., Lethaby A., Farquhar C. Surgery versus medical therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database. Syst. Rev.. (2):2006. Art No. CD003855 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003855.pub2

Marjoribanks J., Proctor M., Farquhar C., et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database. Syst. Rev.. (1):2010. Art No. CD001751 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001751.pub2

NICE. Heavy Menstrual Bleeding, Clinical Guideline 44. London: NICE. 2007.Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11002/30401/30401.pdf.

Prentice A., Deary A., Goldbeck-Wood S., et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (2):1999. Art No. CD000346. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000346.pub2

Proctor M.L., Farquhar C.M., Stones W., et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (1):2002. Art No. CD002123. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002123

Zahradnik H.P., Hanjalic-Beck A., Groth K. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and hormonal contraceptives for pain relief from dysmenorrhea: a review. Contraception. 2010;81:185-196.

Bachmann G., Korner P. Bleeding patterns associated with non-hormonal contraceptives: a review of the literature. Contraception. 2009;79:247-258.

Barnhart K.T., Freeman E.W., Sondheimer S.J. A clinician’s guide to the premenstrual syndrome. Med. Clin. North Am.. 1995;79:1457-1472.

Fall M., Baranowski A.P., Elneil S., et al. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. Eur. Urol.. 2010;57:35-48.

Halbreich U. Women’s reproductive related disorders. J. Affect. Disord.. 2010;122:10-13.

Ismail K.M.K., O’Brien S. Premenstrual syndrome. Curr. Obst. Gynaecol.. 2005;15:25-30.

Lesley D., Acheson N., editors. Endometriosis. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2004.

May K., Octavia-Iacob A., Sweeney C., et al. Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Annual Evidence Update. NHS Evidence – Women’s Health. Oxford: Nuffield Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 2009.

Oelkers W. Drospirenone, a progestogen with antimineralocorticoid properties: a short review. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol.. 2004;217:255-261.

O’Flynn N., Britten N. Menorrhagia in general practice – disease or illness? Soc. Sci. Med.. 2000;50:651-661.

Rapkin A. A review of treatment of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:39-53.

Royal College of Obstericians & Gynaecologists. Green-top Guideline No. 48. Management of Premenstrual Syndrome. Available at http://www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog-corp/uploaded-files/GT48ManagementPremensturalSyndrome.pdf, 2007.