46 Menopause

Menopause

Physiological changes

Ovarian

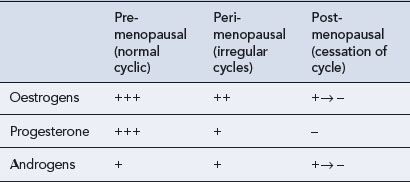

Ovarian function includes two major roles: the production of eggs (gametogenesis) and the synthesis and secretion of hormones (hormonogenesis). Both of these functions undergo subtle changes with ageing so that fewer ova are produced and they are less readily fertilised, and the hormone levels become irregular. It is the granulosa cells in the developing follicle that normally secrete estradiol, and lack of this follicular activity results in diminishing oestrogen secretion. The diminution in the number of active follicles is followed by an increase in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) secretion from the anterior pituitary gland as the normal feedback mechanisms between ovarian estradiol secretion and the hypothalamus–pituitary axis become disrupted. It may be that there is an age-related decrease in sensitivity to feedback inhibition that exacerbates this increase in FSH levels. In women who are still bleeding, an FSH level exceeding 10–12 iu/L on day 2 or 3 of the bleed is indicative of a diminished ovarian response. A high FSH level (above 30 iu/L) and a low estradiol level (below 100 pmol/L) in the plasma characterise menopause. The low oestrogen level fails to stimulate growth of the uterine endometrium. As endometrial growth has not occurred, there can be no menstruation (shedding of the endometrium) and this signifies that menopause has arrived. Since ova are not being released, the production of progesterone from the ovary also ceases and the levels of luteinising hormone (LH) eventually rise. Thus, peri-menopausal and menopausal women are subjected to an increasing ovarian hormone deficiency, as shown in Table 46.1.

Bone

Osteoporosis is defined by WHO as a systemic skeletal disease characterised by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue leading to enhanced bone fragility and a consequent increase in fracture risk. In 2006, WHO estimated that it affects 200 million women worldwide. In addition, approximately 30% of women over the age of 50 have one or more vertebral fractures compared with one in five men over the age of 50 who will have an osteoporosis-related fracture in their remaining lifetime. The total number of hip fractures in 1950 was 1.66 million, and by 2050, this figure could reach 6.26 million. Twenty percent of people die within 1 year of a hip fracture (Cooper, 1997). Typical morbidities after a vertebral fracture include:

To contextualise risk, the remaining lifetime probability in women at menopause of a fracture at any one of these sites exceeds that of breast cancer (~12%). Also, the likelihood of a fracture at any of these sites is 40% or more in developed countries (Kanis et al., 2000), a figure close to the probability of coronary heart disease. Risk factors for osteoporosis include low body mass index (<19 kg/m2), smoking, early menopause, family history of maternal hip fracture, long-term systemic corticosteroid use and conditions affecting bone metabolism, especially those causing prolonged immobility. Osteoporosis is most common in white women. People with osteoporosis are at risk of fragility fractures, occurring as a result of mechanical forces which would not ordinarily cause fracture. The clinically relevant outcome in evaluating treatments for osteoporosis is the incidence of fragility fracture as otherwise this condition is asymptomatic and therefore undiagnosed. The most common sites for these fractures are the hip, vertebrae and wrist. In the UK, the combined cost of hospital and social care for patients with a hip fracture amounts to more than £1.73 billion per year (Torgerson et al., 2001). This is very similar to the annual £1.75 billion health care system costs of coronary heart disease costs. The cost of treating all osteoporotic fractures in post-menopausal women has been predicted to increase to more than £2.1 billion by 2020 (Burge, 2001).

Miscellaneous

Thinning of the skin, brittle nails, hair loss and generalised aches and pains are also associated with reduced oestrogen levels (Hall and Phillips, 2005). The skin is the largest non-reproductive target on which oestrogen acts. Oestrogen receptors, predominantly of the ERβ type, are widely distributed within the skin. Both types of oestrogen receptor (ERα and ERβ) are expressed within the hair follicle and associated structures. Thus, epidermal thinning, declining terminal collagen content, diminished skin moisture, decreased laxity and impaired wound healing (selective ERα ligands are being investigated for their wound-healing properties) have been reported in post-menopausal women.

Psychological changes

Older age at menarche and younger age at menopause are associated with poorer cognitive functioning during ageing. Recent studies have demonstrated that sex steroids have a multifarious and complex relationship with the central nervous system (Hogervorst et al., 2009). For example, there may be a positive correlation between increasing parity and improved executive functioning in response to oestrogen. This temporal relationship between oestrogen deprivation and response to exogenous oestrogen was clearly exemplified in the memory study arm of the WHI (Coker et al., 2010) and MWS studies (Hogervorst and Bandelow, 2010) at the turn of the twenty-first century.

Management

Hormone replacement therapy

Oestrogen therapy

There are four main routes of administration for oestrogens in HRT:

The use of oral oestrogen therapy, while convenient for the patient, does mean that the oestrogen will be subjected to conversion to estrone by the liver and the gut, thereby altering the estradiol:estrone ratio in favour of the less active oestrogen, estrone. The oral preparations have different metabolic effects due to first-pass hepatic metabolism. Smoking stimulates metabolism of oestrogens by cytochrome P450 and decreases plasma oestrogen levels by 40–70% in oral oestrogen users. Smoking has no significant effect on plasma oestrogen levels in users of transdermal preparations. Oral delivery compared to transdermal delivery (Table 46.2) also has different effects on lipid levels (Vrablik et al., 2008). In addition, orally administered oestrogens undergo first-pass hepatic metabolism, which may result in some reduction in anti-thrombin III, a potent inhibitor of coagulation. Implants and patches show smaller changes in coagulation, platelet function or fibrinolysis.

Table 46.2 Effect of HRT administration route on lipid profile

| Oral | Transdermal |

|---|---|

| ↓ Low-density lipoprotein | ↓ Low-density lipoprotein |

| ↓ Total cholesterol | ↓ Total cholesterol |

| ↑ High-density lipoprotein | ↔ High-density lipoprotein |

| ↑ Triglycerides | ↓ Triglycerides |

| ↑ Bile cholesterol | ↔ Bile cholesterol |

More constant levels of oestrogen result from the use of transdermal patches containing estradiol, and these have the added advantage of a more physiological estradiol:estrone ratio (Delmas et al., 1999). However, the adhesive used in these transdermal patches and the alcohol base can cause skin irritation. The patch is applied to the non-hairy skin of the lower body, and care should be taken to ensure that it is placed away from breast tissue. The patch is changed either once or twice a week, thus providing a constant reservoir of estradiol to provide a controlled release into the circulation. Estradiol is also available in a gel formulation, applied daily to the skin over the area of a template (to ensure correct dosage), but this formulation may give erratic absorption. The intranasal preparation, administered as a nasal spray, also avoids hepatic first-pass metabolism.

Oestrogen and progestogen regimens

The monthly withdrawal bleed is perceived by some post-menopausal patients to be an unacceptable side effect of HRT, and this has resulted in the development of a number of regimens in an effort to minimise this effect (Box 46.1). Formulations have been produced with which bleeding only occurs every 3 months instead of every 4 weeks, or it does not occur at all.

Not all progestogens have the same pharmacological profile and these differences have implications for their usage. Two of the most widely used synthetic progestogens are medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone. These are used as the progestogenic component of an HRT regimen in combination with oestrogen but have been shown to increase the risk of breast cancer in long-term HRT users (Million Women Study Collaborators, 2003; Women’s Health Initiative, 2002). Structurally, medroxyprogesterone acetate is more similar to natural progesterone than norethisterone. The metabolism of these two compounds is also different, as medroxyprogesterone acetate is the major progestogenic compound rather than one of its metabolites. In contrast, the metabolites of norethisterone exhibit significant activity in addition to a wide range of non-progestogenic actions. Norethisterone also binds to sex hormone–binding globulin, whereas medroxyprogesterone acetate does not.

Alternatives to HRT

A Cochrane review supports the efficacy of strontium ranelate for the reduction of fractures in post-menopausal osteoporotic women (O’Donnell et al., 2006). The main side effect reported was diarrhoea, but the potential vascular and neurological side effects should be explored further. National guidance (NICE, 2010) details the role of alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene and strontium ranelate for the primary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in post-menopausal women.

Treatment with HRT

Bone

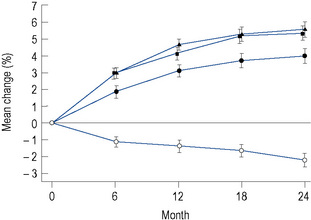

The greatest effect of oestrogen on bone is seen with implants, where an approximately 8% increase in vertebral bone density is seen within 1 year of treatment. Estradiol patches are the next most effective route of administration (Fig. 46.1), while oral therapy only achieves an increase in bone density of about 2% per annum. However, 5 years of oral oestrogen therapy will still achieve a lifetime reduction in femoral neck fracture of as much as 50%.

Oestrogen improves the quality and quantity of bone in the post-menopausal woman. It may be started at any time after menopause, and the benefit will continue for the duration of treatment. Bone loss will continue after treatment ceases, which leads into the difficult area of how long treatment should continue. It was previously recommended that to obtain maximum benefit from treatment with oestrogen, the duration of the course should be at least 10 years. However, studies have identified some potential adverse effects of HRT (Million Women Study Collaborators, 2003; Women’s Health Initiative, 2002). Therefore, this recommendation is controversial, particularly in women with an intact uterus, where a combined HRT preparation is required as there is probably a greater risk of adverse outcome. Oestrogen given systemically in the peri-menopausal and post-menopausal period or tibolone given in the post-menopausal period also diminishes post-menopausal osteoporosis, but other drugs are preferred.

Cardiovascular system

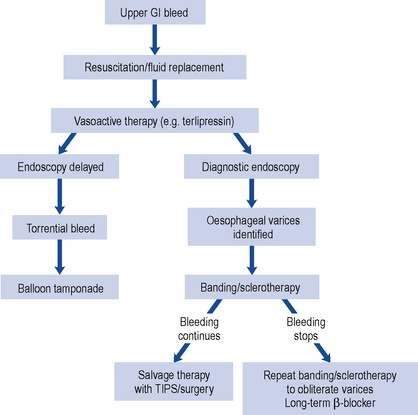

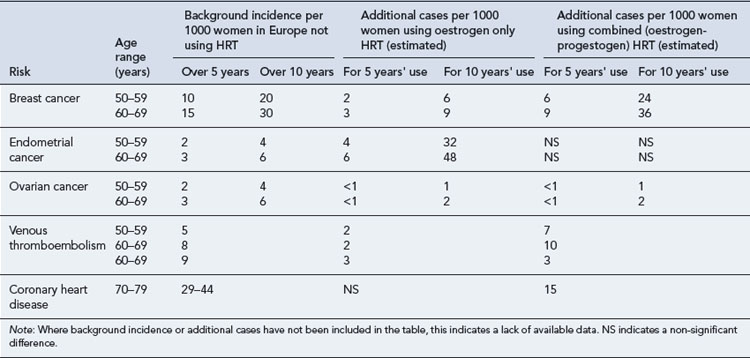

The estimated influence of HRT on the incidence of coronary heart disease, venous thromboembolism and stroke is summarised in Table 46.3.

Table 46.3 Estimated influence of HRT on incidence of gynaecological cancers, venous thromboembolism, stroke and CHD (MHRA/CHM, 2007)

Coronary heart disease

Women at 45 years are significantly less likely than men to die of coronary heart disease, but by the age of 60 years, the death rate from the disease is similar in both sexes. Oestrogen is probably central to this gender difference as women who experience early loss of endogenous estradiol have an accelerated risk of developing coronary heart disease. Intuitively, it would appear logical that post-menopausal women would gain benefit from receiving exogenous oestrogen. However, there are conflicting views as to whether this is, or is not, the case. A 4-year study of women with coronary heart disease in the USA (Heart and Estrogen-Progestin Replacement Study, HERS) who were also receiving HRT (conjugated equine oestrogen and medroxyprogesterone acetate) demonstrated no significant reduction in stroke (Simon et al., 2001). This was in contrast to the increased risk of myocardial infarction in the first year of starting HRT in the original HERS report (Hulley et al., 1998). The Women’s Health Initiative (2002), another US-based study, also reported an increase in coronary events in the first year of receiving HRT.

The relevance of both studies to UK practice has been challenged as both involved use of conjugated equine oestrogen/medroxyprogesterone acetate regimens. In the UK, natural progesterone is preferred, and this differs from medroxyprogesterone acetate in that it does not attenuate the beneficial effects of oestrogen in reducing the development of coronary artery atherosclerosis and protecting against coronary vasospasm. A study (De Vries et al., 2006) using the UK General Practice Research Database found HRT was associated with a decrease in risk of acute myocardial infarction, and there was no difference between the different oestrogen–progestogen combinations. A recent study found that transdermal but not oral oestrogen replacement therapy significantly reduced atherogenic index of plasma (Vrablik et al., 2008). This occurred by increasing HDL particle size and therefore improving the antiatherogenic properties.

The International Menopause Society consensus statement (2009) states that HRT can be given to women around the age of natural menopause without increasing the risk of coronary heart disease and may even decrease the risk in this age group. HRT is not contraindicated in women with hypertension, and in some cases, HRT may even reduce blood pressure. HRT is contraindicated in women with a history of myocardial infarction, stroke or pulmonary embolism.

Venous thromboembolism

It is known that the oestrogen in the combined oral contraceptive pill contributes to thromboembolic disorders. Whether the same applies to the oestrogen in HRT is unclear as the dose of oestrogen found in HRT is much lower and more physiological than that in the oral contraceptive pill. Analysis of the results from the Women’s Health Initiative (2002) has confirmed that there is an increased risk of pulmonary embolism with HRT and the risk is greater with oral HRT than transdermal oestrogen.

Oral oestrogen, in contrast to the transdermal route, undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism. This increases the production of prothrombotic factors in the liver and is associated with a reduction in fibrinogen and factor VII activation, such as von Willebrand’s factor and anti-thrombin, and enhanced fibrinolysis (RCOG, 2004). HRT is also associated with increased resistance to activated protein C.

Whilst oestrogen exposure and age increase the risk of venous thromboembolism, they do not explain the increased risk seen in the first year of HRT use. An underlying thrombophilia, a known risk in hyperoestrogenic situations, is thought to be the additional factor that makes certain women susceptible to venous thromboembolism. Guidelines (RCOG, 2004) to manage the risk of venous thromboembolism have been produced for women starting or continuing HRT (Box 46.2). The selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMS) such as raloxifene are considered to carry the same risk of thrombosis as oestrogen-containing HRT.

(adapted from RCOG, 2004)

Women starting or continuing HRT

Women with a personal or family history of VTE

Cancer

Details of the estimated influence of HRT on the incidence of cancer are presented in Table 46.3.

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most common cause of disease and death in middle-aged women, affecting around one in 11 women before the age of 75 in developed countries. Over the past 20 years, there has been a growing body of evidence to suggest that progesterone contributes to the development of breast cancer. Evidence to support this came from trials in which use of combined regimens increased breast cancer risk more than oestrogen alone. This is thought to have occurred because the synthetic progestogens possessed some non-progesterone like effects that potentiated the proliferating action of oestrogen. In the USA, the most commonly used progestogen in HRT was medroxyprogesterone acetate combined with conjugated equine oestrogen and administered orally. In contrast, in central and southern Europe, a wider range of progestogens is used, particularly the 19-nortestosterone derivatives. Studies investigating the use of natural micronised progesterone to improve bioavailability in HRT regimens have demonstrated no increased risk of breast cancer. In vitro studies with medroxyprogesterone have found it promotes the reproductive transformation of estrone into estradiol by influencing the activity of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. The properties of the synthetic progestogens are outlined in Table 46.4.

Table 46.4 Properties of progestogens and their link to breast cancer

| Progestogen | Action |

|---|---|

| 19-Nortestosterone derivatives, medroxyprogesterone acetate | Oestrogenic activity Influence on 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase |

| 19-Nortestosterone derivatives, medroxyprogesterone acetate | Metabolic effects, opposing those of oestrogen, on insulin sensitivity. Hepatic effects, opposing those of oestrogen, that is increasing IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor), decrease in sex hormone-binding globulin |

| 19-Nortestosterone derivatives | Binding to sex hormone-binding globulin with consequent reduction in capacity to bind oestrogen |

(adapted from Campagnoli et al., 2005)

The relationship between different HRT regimens and breast cancer is complex (Table 46.4). There are many potential confounders to be considered when interpreting trial data, for example, time of initiation of therapy, in relation to menopausal status, body mass index, prior hormone use, etc. Chlebowski et al. (2009) reported on the decline in breast cancer in the USA after a reduction in HRT usage following publication of the WHI trial (2002). This prompted a response from the President of the International Menopause Society (Sturdee, 2009) summarised as follows:

Notwithstanding these arguments, the problem on what to advise women contemplating HRT can be problematic. Current advice recommends that the minimum effective dose of HRT should be used for the shortest duration, but for the treatment of menopausal symptoms the benefits of short-term HRT outweigh the risks in the majority of women, especially in those aged under 60 years (Joint Formulary Committee, 2010).

Psychological symptoms

Psychological symptoms include:

Central nervous system

The relationship between oestrogen and neurodegenerative conditions, in particular, Alzheimer’s disease (Mulnard et al., 2000), has received attention in the light of an observation that there is an increased incidence of the disease in older women. The development of plaques of amyloid-β, a protein that disrupts nerve cell connections in the brain, occurs more rapidly in the absence of oestrogen. This effect of amyloid-β production results in the symptoms of short-term memory loss and disorientation which occur in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Further studies are essential to clarify the relationship between HRT and Alzheimer’s disease. There is some evidence that heavier women, who have higher free estradiol levels, exhibit better cognitive function in several domains. Such women may also have a greater clinical response when using exogenous oestrogen. It should also be noted that conjugated equine oestrogen is composed primarily of oestrone sulphate and this oestrogen has a much lower affinity for oestrogen receptors than oestradiol. Hence, the findings with respect to exogenous oestrogen and neurological function remain equivocal. The length of oestrogen deprivation before supplementation is also important as early administration of oestrogen for a period of several years may yet be found to be beneficial. Evidence is emerging that the progestogenic component in combined HRT is important and medroxyprogesterone acetate usage has been associated with negative cognitive outcomes. The potential of selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) as neuroprotectants has been evaluated in a breast cancer prevention trial which compared tamoxifen with raloxifene (Yaffe et al., 2001). Both agents were found to have similar effects on cognition. It is possible that HRT may have a neuroprotective effect under certain circumstances in some women and neuroimaging, for example, PIB (Pittsburgh compound B – a fluorescent agent). PET scanning may reveal effects not detectable using cognitive testing.

Answers

Answers

Answers

Burge R.T. The cost of osteoporotic fractures in the UK. Projections for 2000–2020. J. Med. Econ.. 2001;4:51-62.

Campagnoli C., Abbà C., Ambroggio S., et al. Pregnancy, progesterone and progestins in relation to breast cancer risk. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol.. 2005;97:441-450.

Chlebowski R.T., Kuller L.H., Prentice R.L., et al. Breast cancer after use of estrogen plus progestin in postmenopausal women. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2009;360:573-587.

Coker L.H., Espeland M.A., Rapp S.R., et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and cognitive outcomes: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS). J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol.. 2010;118:304-310.

Cooper C. The crippling consequences of fractures and their impact on quality of life. Am. J. Med.. 1997;103(2A):12S-17S.

Delmas P.D., Pornel B., Felsenberg D., et al. A dose-ranging trial of a matrix transdermal 17β-estradiol for the prevention of bone loss in early postmenopausal women. Bone. 1999;24:517-523.

De Vries C.S., Bromley S.E., Farmer R.D.T. Myocardial infarction risk and hormone replacement: differences between products. Maturitas. 2006;53:343-350.

Hall G., Phillips T.J. Oestrogen and skin: the effects of estrogen, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy on the skin. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.. 2005;53:555-568.

Hulley S., Grady D., Bush T., et al. Randomised trial of oestrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 1998;280:605-613.

Hogervorst E., Henderson V.W., Gibbs R.B., et al, editors. Hormones, Cognition and Dementia: State of the Art and Emergent Therapeutic Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Hogervorst E., Bandelow S. Sex steroids to maintain cognitive function in women after the menopause: a meta-analyses of treatment trials. Maturitas. 2010;66:56-71.

International menopause consensus statement. Aging, menopause, cardiovascular disease and HRT. Climacteric. 2009;12:368-377.

Joint Formulary Committee. London: British National Formulary. BNF BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. 2010.

Kanis J.A., Johnell O., Oden A., et al. Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmo. Osteoporos. Int.. 2000;11:669-674.

MHRA/CHM. Drug safety advice. Drug Safety Update. 2007;1(2):2-6. Available at http://www.mhra.gov.uk/mhra/drugsafetyupdate Access date 10th August 2010

Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2003;362:419-427.

Mulnard R.A., Cotman C.W., Kawas C., et al. Oestrogen replacement therapy for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2000;283:1007-1015.

National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence, Technology Appraisal 160. Alendronate, Etidronate, Risedronate, Raloxifene and Strontium Ranelate for the Primary Prevention of Osteoporotic Fragility Fractures in Postmenopausal Women (Amended). London: NICE. 2010. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/TA160 Access date 10th August 2010

O’Donnell S., Cranney A., Wells G.A., et al. Strontium ranelate for preventing and treating postmenopausal osteoporosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006. Issue 4. Art. No.: CD005326 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005326.pub3

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Guideline 19. Hormone Replacement Therapy and Venous Thromboembolism. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2004. Available at http://www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog-corp/uploaded-files/GT19HRTVenousThromboembolism2004.pdf Access date 10th August 2010

Simon J.A., Hsia J., Cauley J.A., et al. Postmenopausal hormone and risk of stroke. Heart and Estrogen-progestin Replacement Study (HERS). Circulation. 2001;103:638-642.

Sturdee D. President of the International Menopause Society commenting on ‘NEJM Article on Breast Cancer and HRT – Comment by International Menopause Society’. 2009. Available at http://www.imsociety.org/pages/comments_and_press_statements/ims_press_statement_04_02_09.php Access date 10th August 2010

Torgerson D., Iglesias C., Reid D.M. The effective management of osteoporosis. In: Barlow D.H., Francis R.M., Miles A., editors. The Economics of Fracture Prevention. London: Aesculpius Medical Press; 2001:111-121.

Vrablik M., Fait T., Kovar J., et al. Oral but not transdermal estrogen replacement therapy changes the composition of plasma lipoproteins. Metab. Clin. Exp.. 2008;57:1088-1092.

Women’s Health Initiative. Risks and benefits of oestrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2002;288:321-333.

Yaffe K., Krueger K., Sarkar S., et al. Cognitive function in postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2001;344:1207-1213.

Brockie J. Alternative approaches to the menopause. Rev. Gynaecol. Pract.. 2005;5:1-7.

Dantas A.P.V., Sandberg K. Challenges and opportunities associated with targeting oestrogen receptors in treating hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Drug Discov. Today Ther. Strateg.. 2005;2:245-251.

Dubey R.K., Imthurn B., Barton M., et al. Vascular consequences of menopause and hormone therapy: importance of timing of treatment and type of estrogen. Cardiovasc. Res.. 2005;66:295-306.

Dunkin J., Rasgon N., Wagner-Steh K., et al. Reproductive events modify the effects of estrogen replacement therapy on cognition in healthy postmenopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:284-296.

Gallagher J.C. Advances in bone biology and new treatments for bone loss. Maturitas. 2008;60:65-69.

Hogervorst E., Bandelow S. Sex steroids to maintain cognitive function after the menopause: a meta-analyses of treatment trials. Maturitas. 2010;66:56-71.

Kanis J.A., Burlet N., Cooper C., et al. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporosis International. 2008;19:399-428. doi:10.1007/s00198–008–0560-z

Panay N., Rees M. Alternatives to hormone replacement therapy for management of menopausal symptoms. Curr. Obstet. Gynaecol.. 2005;15:259-266.

Sturdee D.W. The menopausal hot flush: anything new? Maturitas. 2008;60:42-49.