Chapter 34 Meningitis and Encephalitis in the Intensive Care Unit

Meningitis

4 What host factors are important to consider regarding risk and cause for acute bacterial meningitis?

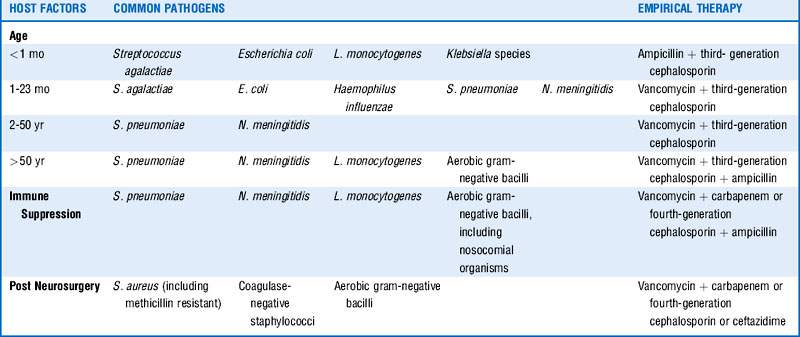

Factors such as age, immune deficiency or suppression, recent central nervous system (CNS) instrumentation, and possible exposures should be considered and will influence empirical therapy. See Table 34-1.

5 What are the most common causes of community-acquired acute bacterial meningitis in adults?

Table 34-2 includes the most common organisms in descending order based on case series with preferred antimicrobial therapy and suggested duration of treatment.

Table 34-2 Most Common Causes of Community-Acquired Bacterial Meningitis in Adults

| Pathogens | Preferred antimicrobial | Suggested duration of therapy |

|---|---|---|

| S. pneumoniae PCN MIC < 0.1 mcg/mL PCN MIC 0.1-1 mcg/mL PCN MIC ≥ 2 mcg/mL |

PCN or ampicillin Third-generation cephalosporin Vancomycin + third-generation cephalosporin |

10-14 days |

| N. meningitidis PCN MIC < 0.1 mcg/mL PCN MIC > 0.1 mcg/mL |

PCN or ampicillin Third-generation cephalosporin |

7 days |

| L. monocytogenes | Ampicillin or PCN | ≥ 21 days |

| Streptococcus agalactiae, pyogenes | Ampicillin or PCN | 21 days |

| S. aureus | MSSA → nafcillin, oxacillin MRSA → vancomycin |

14 days |

| H. influenzae β-Lactamase negative β-Lactamase positive |

Ampicillin Third-generation cephalosporin |

7 days |

MIC, Minimum inhibitory concentration; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus; PCN, penicillin.

10 Is there harm in awaiting CT and LP results before initiating therapy?

Initiate antibiotic therapy and steroids.

Initiate antibiotic therapy and steroids.

Obtain CT of head, and perform LP if safe. CSF cultures may be affected by pretreatment with antibiotics before lumbar puncture, but CSF findings including cell counts, chemical analyses, and Gram stain should remain helpful. Van de Beek, in his review, noted that yield of Gram stain was similar in patients who had been treated with antibiotics before LP as compared with those who had not.

Obtain CT of head, and perform LP if safe. CSF cultures may be affected by pretreatment with antibiotics before lumbar puncture, but CSF findings including cell counts, chemical analyses, and Gram stain should remain helpful. Van de Beek, in his review, noted that yield of Gram stain was similar in patients who had been treated with antibiotics before LP as compared with those who had not.

11 What CSF studies are important?

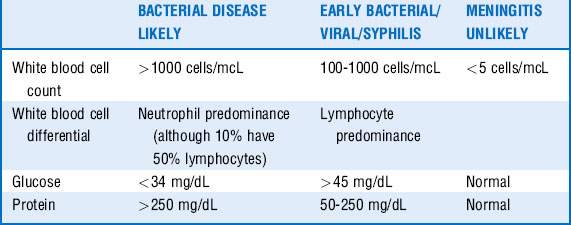

A number of guides help determine likelihood for bacterial meningitis based on various CSF markers, although it is important to know that none are absolute. See Table 34-3 for specific indicators.

13 In the setting of documented bacterial meningitis, who gets postexposure prophylaxis?

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally (PO) × 1

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally (PO) × 1

Rifampin 10 mg/kg PO every 12 hours for 2 days (or 600 mg every 12 hours in adults)

Rifampin 10 mg/kg PO every 12 hours for 2 days (or 600 mg every 12 hours in adults)

Ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly (IM) × 1 in adults; 125 mg IM × 1 in children

Ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly (IM) × 1 in adults; 125 mg IM × 1 in children

2. H. influenzae: If there is a partially vaccinated child or child younger than 4 years of age, prophylaxis is suggested for all household contacts, including adults. Prophylaxis of day-care contacts can be considered if applicable. The highest risk is in children under the age of 2 years.

15 What are important historical data to obtain to help determine possible etiologic viral pathogens?

The list of possible causes is extensive. Various factors can help narrow the possibilities. See Box 34-1.

Encephalitis

18 What are the most common causes of acute encephalitis?

Possible infectious causes include but are not limited to the following:

Viral: HSV-1, enterovirus, WNV, VZV, SLE, influenza, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, measles, rabies, cytomegalovirus (CMV)

Viral: HSV-1, enterovirus, WNV, VZV, SLE, influenza, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, measles, rabies, cytomegalovirus (CMV)

Bacterial: Bartonella henselae, L. monocytogenes

Bacterial: Bartonella henselae, L. monocytogenes

Rickettsial: Ehrlichia, Rickettsia rickettsii, Anaplasma

Rickettsial: Ehrlichia, Rickettsia rickettsii, Anaplasma

Parasitic: Toxoplasma gondii, Naegleria fowleri

Parasitic: Toxoplasma gondii, Naegleria fowleri

Fungal: Histoplasma capsulatum, Cryptococcus neoformans, Coccidioides immitis

Fungal: Histoplasma capsulatum, Cryptococcus neoformans, Coccidioides immitis

1 Attia J., Hatala R., Cook D., et al. Does this adult patient have acute meningitis? JAMA. 1999;281:175–181.

2 Durand M., Calderwood S., Weber D., et al. Acute bacterial meningitis in adults: a review of 493 episodes. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:21–28.

3 Gans J.D., Van de Beek D. Dexamethasone in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1549–1556.

4 Hasbun R., Abrahams J., Jekel J., et al. Computed tomography of the head before lumbar puncture in adults with suspected meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1727–1733.

5 Leib S., Boscacci R., Gratzl O., et al. Predictive value of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) lactate levels versus CSF/blood glucose ratio for the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis following neurosurgery. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:69–74.

6 Lepper M.H., Dowling H.F. Treatment of pneumococcic meningitis with penicillin compared with penicillin plus aureomycin; studies including observations on an apparent antagonism between penicillin and aureomycin. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1951;88:489–494.

7 Mayefsky J.F., Roghmann K.J. Determination of leukocytosis in traumatic spinal tap specimens. Am J Med. 1987;82:1175–1181.

8 Sawyer M.H., Rotbart H.A. Viral meningitis and aseptic meningitis syndrome. In: Scheld W.M., Whitley R.J., Marra C.M. Infections of the Central Nervous System. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:75–93.

9 Tunkel A.R., Glaser C.A., Bloch C.B., et al. The management of encephalitis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:303–327.

10 Tunkel A.R., Hartman B.J., Kaplan S.L., et al. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1267–1284.

11 Tunkel A.R., Van de Beek D., Scheld W.M. Acute meningitis. In: Mandell G., Bennett J., Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2010:1189–1229.

* Ten times this predicted count has been shown to be a sensitive and specific indicator of meningitis in the setting of traumatic LP.