CHAPTER 61 Meningiomas

A Patient’s View

WHEN THE BIG ONE HITS

Meningiomas and earthquakes share similar characteristics:

The litany of labels continued:

Then finally, the cure for my blues—Prozac.

AFTERSHOCKS ABOUND

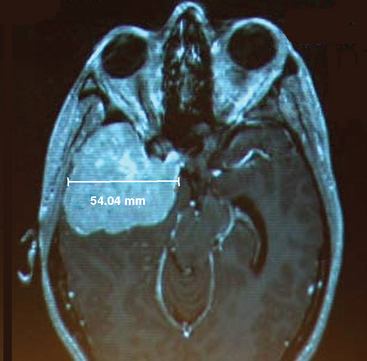

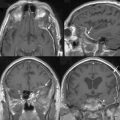

Just hours after receiving my meningioma diagnosis, Mark and I met my neurosurgeon for the first time. It wasn’t until the formal introductions were over that I noticed my stark MRI pictures illuminated on the wall—snapshots of my brain. Located in the epicenter of my control center was an unwelcome guest staring back at me in defiance (Fig. 61-1). Stunned but attempting to sweep up those million little pieces, I mustered up some semblance of my trademark sense of humor.