Evidence-Based Medicine

The formal definition of evidence-based medicine (EBM) is “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.”1 This definition is useful but leaves ambiguities. What does “explicit” mean? How might we define “judicious”? What constitutes “evidence”? And perhaps most important, who is “making decisions,” the doctor or the patient?

Broadly introduced to medical culture in 1992, EBM has exploded in the past 2 decades.2 The term has become ubiquitous and is often co-opted by working groups, professional societies, and individual authors who neither systematically adhere to core EBM principles nor complete the fundamental tasks that define EBM. In addition, the most important principle underlying medical practice and the Hippocratic Oath—that the physician’s goals should be aligned with the patient’s goals—has not been routinely integrated into these applications of EBM.

Clinical Scenarios

Acute Headache in the Emergency Department

Ask

The prevalence of SAH varies considerably across practice settings and research cohorts, which is often a reflection of biases such as spectrum bias, or enrollment of an overly narrow or broad spectrum of patients, and referral bias, which is one type of spectrum bias and typically occurs when a study enrolls only a referred patient cohort. A recent publication of patients referred to a neurosurgical department for headache suspicious of SAH found a remarkable prevalence of 59%.3 In contrast, in a large retrospective study of nearly all patients with headache encountered in an ED, only 1% were found to have SAH.4 In the second example, a broad cohort with limited inclusion or exclusion criteria related to headache quality was evaluated, and very few had the disease of interest. Conversely, when only a highly selected population of patients with headache referred to a neurosurgeon were studied, the majority had significant pathology. Ideally, any study that we use to generate a risk estimate for Ms. Mason should be from the ED setting and should enroll those with a similarly “acute” headache.

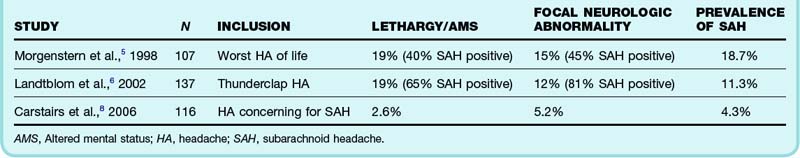

Further refining our question, we note that Ms. Mason is awake and alert with normal findings on neurologic examination. One review has suggested that 15% of patients seen in the ED with a thunderclap headache have SAH, but the two studies in this review did not distinguish between neurologically compromised and normal patients.5,6 In both studies, one in five patients enrolled was noted to have either lethargy or altered mental status. Not surprisingly, another prospective study in which fewer patients with abnormal neurologic findings were enrolled found a much lower prevalence of disease7 (Table 1).

Acquire

One of the first papers found is a recent publication by Perry et al.: “High Risk Clinical Characteristics for Subarachnoid Haemorrhage in Patients with Acute Headache: Prospective Cohort Study.”9 Scanning the abstract, we decide that it meets many of our important inclusion criteria and thus embark on the third part of the EBM process.

Apply

When the diagnosis of SAH is being pursued, the current recommended approach includes a CT scan, followed by LP when imaging is negative.10 Based on study design and disease prevalence, the sensitivity of CT has varied widely across research populations, between 82% and 100%, and this has been judged inadequate in the context of the disease.8 Although a recent investigation of CT for SAH reported a sensitivity approaching 100%, spectrum bias was evident because all the subjects were referred to a neurosurgical center for evaluation.3

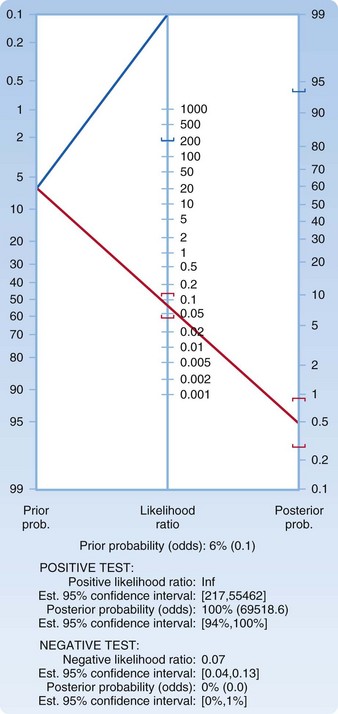

We decide to presume a worst-case scenario for the imaging test and choose an LR of 0.13, which represents the upper boundary of the confidence interval. Plotting a pretest probability of 6.5% on a Fagan nomogram and using an LR of 0.13, we generate a posttest probability of just under 1% (Fig. 1). You explain to the patient that a less than 1 in 100 chance (1 in 118 to be exact) persists that she has SAH detectable by LP. She carefully considers these numbers and asks another question: “How much lower would her risk be if LP were performed and determined to be normal?” In the EBM style of practice, one question often begets another. We return to the acquire and appraise steps.

The aforementioned literature search yields a paper by Perry et al.: “Is the Combination of Negative Computed Tomography and Negative Lumbar Puncture Result Sufficient to Rule Out Subarachnoid Hemorrhage?”11 In this study of 592 subjects, a subset of patients from the cohort described earlier by Perry et al., all patients with suspected SAH underwent CT and LP. Of those in whom both tests were negative, the posttest probability or risk of having SAH was 0.0001%, or 1 in a million.

Any discussion of the potential benefits of detection of SAH must first start by distinguishing between aneurysmal and nonaneurysmal disease. Published case series of patients with SAH suggest that roughly 85% of cases of SAH can be attributed to leak or rupture of an aneurysm.12 Of the 15% that are nonaneurysmal in origin, most are classified as “perimesencephalic” bleeding events in the absence of a vascular aneurysm. Small case series suggest that patients with perimesencephalic SAH have an almost universally good prognosis.13,14 Of equal importance, no neurosurgical intervention is performed for these patients.

An extensive search yields several related papers reporting on the results of the Cooperate Aneurysm Study, a randomized trial of patients with intracranial aneurysms and SAH performed in the 1960s.15 There were four treatment arms: regulated bed rest, drug-induced hypotension with bed rest, ipsilateral common carotid artery ligation and bed rest, and intracranial surgery. As the authors of the study suggest, the group receiving regulated bed rest offered the best representation of the natural history of SAH resulting from a ruptured intracranial aneurysm.

In addition to improvements in neurosurgical interventions, medical advancements since the 1960s have resulted in many beneficial treatments for patients with SAH, including drugs such as calcium channel blockers.16 In one of the most recent, high-quality trials comparing endovascular treatment with standard neurosurgery, in which 88% of the patients were enrolled in good neurologic condition, 23.5% of those in the superior therapy arm, endovascular treatment, were dead or dependent at 1 year.17 A large, prospective observational study that enrolled more than 3500 patients with aneurysmal SAH reported similar survival data for patients initially admitted in good neurologic condition.18 Clearly, the contemporary cohorts fare better than patients with similar disease randomized to bed rest in the 1960s because 76% are alive with good function in some treatment groups, but it is critical to note that even with the best, most modern interventions, a substantial percentage of patients still have poor outcomes.

The patient considers this information and decides to forgo the test. She understands that the disease has not been completely “ruled out” and that a negative LP would substantially lower her risk of having the disease.11 In the medical chart you document that an extensive discussion regarding the risks and benefits of testing has transpired. You discharge the patient with a diagnosis of headache and tell her to return immediately should her symptoms return or any other concerning symptoms develop.

Chest Pain in the Emergency Department

Background

Approximately 8 million patients seek treatment in the ED for chest pain each year, and these patients are often admitted for a work-up to rule out cardiac disease. It has been suggested that a large proportion of hospitalizations are unnecessary and that many patients undergo expensive and sometimes invasive testing.19 Conversely, studies also suggest that between 2.1% and 4.6% of patients with myocardial ischemia are initially discharged.20 Groups that seem to be at highest risk for discharge during an initial coronary manifestation are women, nonwhites, and those with a nondiagnostic initial ECG.21 Given the significant morbidity and mortality associated with myocardial ischemia, it is crucial that patients at risk for poor outcomes be quickly and accurately identified. The challenge for the emergency physician is in accurately stratifying risk so that patients and physicians can make clinical decisions informed by valid and relevant evidence.

Prognosis is dependent on a number of patient characteristics, which are referred to as prognostic factors—factors that affect the outcome of the disease. These factors are not necessarily the same as risk factors, which are characteristics associated with the development of a disease. For example, in the case of our patient, gender may be considered a risk factor for heart disease, but it is not necessarily associated with a specific outcome. In contrast, the patient’s normal ECG on arrival may be considered a prognostic factor if it is found to be associated with a better overall prognosis. In the case of cardiac disease, studies show that risk factors for cardiac disease are not generally useful in identifying acute coronary syndrome (ACS), except in the case of young patients, in whom the presence of four or more of these risk factors has been associated with a significantly increased likelihood of ACS.22

Acquire and Appraise

One option to consider, particularly when attempting to acquire evidence in an active setting of patient care (when time restraints are important), is to defer to established sources of already appraised and summarized data. One such “preappraised resource” is BestBets, a website respected by many EBM users that offers brief and simple summaries of evidence-based reviews of topics. In this case a quick BestBets search for this topic reveals an article titled “The First ECG Has Low Sensitivity for Myocardial Infarction in Patients with Chest Pain” (2000).23 This article examined 10 studies conducted between 1976 and 1998 that sought to assess the prognostic value of an ECG and reported sensitivities ranging from 13% to 69%. The article concluded that an initial ECG cannot be used to rule out MI. At first it seems that this review is helpful. However, on reconsideration, we realize that although information about the ECG may be generally useful, it is specific neither to our patient nor to our question, which is about prognosis. This review seems focused on the diagnostic performance (sensitivity) of a particular test (ECG).

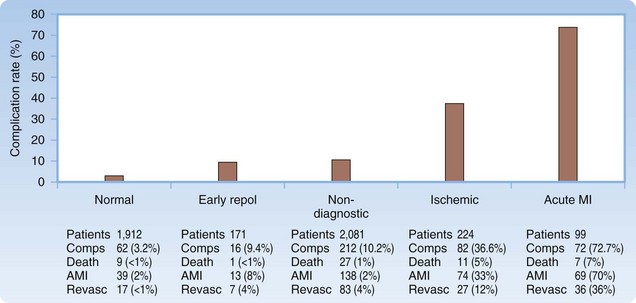

We therefore move to performing a MEDLINE search, a fundamental skill set that is our next logical step when preappraised resources do not provide the answer. Our search, which focuses on the prognosis of patients with chest pain and low-risk features, reveals two potentially relevant and recent prospective studies. These studies distinguished between rates of MI and rates of death and had initial ECGs analyzed by physicians blinded to patient outcomes. ECGs were classified into one of a number of groups ranging from normal to acute ST-segment elevation MI. The prospective studies quoted mortality rates lower than 1% for patients with normal ECG findings.19,24 These studies used slightly different cohorts, and the follow-up times also differed between studies. The study that is probably most relevant to our patient is the study by Forest et al., which involved 3814 adults older than 24 years who had an ECG performed for chest pain. This study found that 2% of patients with an initial normal ECG eventually suffered MI within 30 days [39 of 1912 patients], and 0.5% died [9 of 1912]24 (Fig. 2).

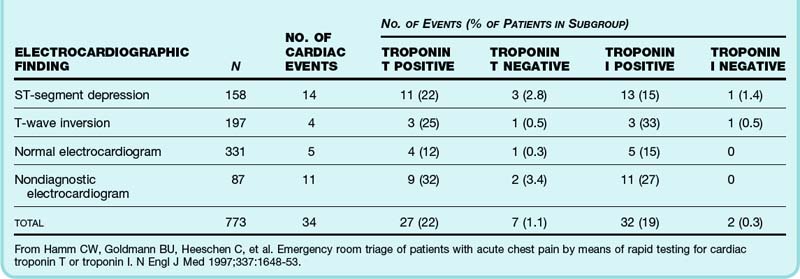

The next step in your analysis might be to ask whether the patient’s prognosis would be altered by the inclusion of cardiac enzyme testing. In this patient with a somewhat concerning description of pain and no clear diagnosis, it would be reasonable to consider cardiac enzyme testing. However, if these tests are performed and come back negative, what is the next step? Should another set of enzyme testing be performed? Can your patient go home? This is a somewhat more complicated question to test than the ECG question because there are a variety of laboratory tests available and a variety of protocols for tracking cardiac enzymes. A MEDLINE search for “cardiac enzyme” or “troponin” along with “chest pain” and “prognosis” yields a number of studies that monitored outcomes in patients with negative initial enzymes. One of the most high quality of these was done by Hamm et al. in Germany: “Emergency Room Triage of Patients with Acute Chest Pain by Means of Rapid Testing for Cardiac Troponin T or Troponin I.”25 Patients were enrolled if they had acute anterior, precordial, or left-sided chest pain for less than 12 hours. All patients had a troponin test done on arrival and 4 hours later, and those experiencing chest pain for less than 2 hours had another test sent at hour 6 (only 3% of subjects). This was a relatively high-risk cohort in which 30% were admitted to the intensive care setting. When troponin I testing was negative in the ED setting, the 30-day risk for death or MI was 0.3% (Table 2).

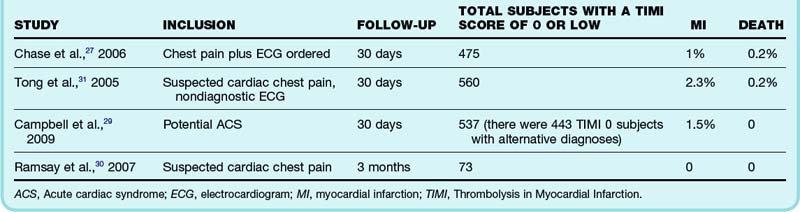

The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] risk score has been tested in multiple populations, and most studies of chest pain patients assign a TIMI risk score to subjects. This score (see Box 1) uses seven prognostic factors, with each assigned 1 point, to create an overall risk score. The score was originally derived by using a population of patients with unstable angina or non–ST elevation MI and was used successfully to risk-stratify these patients.26 It was then externally validated in a population of patients with undifferentiated chest pain.27 Thus the score seems reproducible, valid, and applicable to a variety of populations. For these reasons, virtually all decision aid studies of patients with chest pain classify patients by TIMI risk score. Therefore we can quickly and easily calculate the TIMI risk score of our patient (it is 0) and then look at these observational data to see what the risk for MI or death was for study patients with the same risk score. Unfortunately, not all studies reported rates of MI or death separately but instead reported them in a composite outcome, including the end point, revascularization. From an EBM perspective, this last end point is problematic for two reasons. First, a high degree of subjectivity enters into decision making about which patients undergo revascularization, and second, its utility in patients not actively experiencing an MI is dubious, thus limiting its function as a “patient-important outcome.”28 There are four studies that reported MI, death, and revascularization rates separately, two of which actually used a modified TIMI scoring system in which subjects were classified as low, moderate, or high, with low representing a score of 2 or less27,29–31 (Table 3). With approximately 1600 subjects across these studies, for patients with a TIMI risk score of 0 or low, the reported rates of MI and death at 30 days were 0% to 2% and 0% to 0.2%, respectively. For 400 subjects with a TIMI score of 0 and an alternative diagnosis per treating emergency physician, the death rate was 0.8%.29 Translating this into understandable numerical values, in patients classified as low risk by TIMI scoring, the 30-day risk for MI is lower than 1 in 50, whereas the risk for death is less than 1 in 500.

1 Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71–72.

2 Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268:2420–2425.

3 Cortnum S, Sørensen P, Jørgensen J. Determining the sensitivity of computed tomography scanning in early detection of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:900–902. discussion 903

4 Perry JJ, Stiell I, Wells G, et al. Diagnostic test utilization in the emergency department for alert headache patients with possible subarachnoid hemorrhage. CJEM. 2002;4:333–337.

5 Morgenstern LB, Luna-Gonzales H, Huber JC, et al. Worst headache and subarachnoid hemorrhage: prospective, modern computed tomography and spinal fluid analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:297–304.

6 Landtblom A, Fridriksson S, Boivie J, et al. Sudden onset headache: a prospective study of features, incidence and causes. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:354–360.

7 Carstairs SD, Tanen DA, Duncan TD, et al. Computed tomographic angiography for the evaluation of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:486–492.

8 Carstairs SD, Tanen DA, Duncan TD, et al. Computed tomographic angiography for the evaluation of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:486–492.

9 Perry JJ, Stiell IG, Sivilotti MLA, et al. High risk clinical characteristics for subarachnoid haemorrhage in patients with acute headache: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c5204.

10 Edlow JA, Panagos PD, Godwin SA, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with acute headache. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:407–436.

11 Perry JJ, Spacek A, Forbes M, et al. Is the combination of negative computed tomography result and negative lumbar puncture result sufficient to rule out subarachnoid hemorrhage? Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:707–713.

12 van Gijn J, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage: diagnosis, causes and management. Brain. 2001;124:249–278.

13 Brilstra EH, Hop JW, Rinkel GJ. Quality of life after perimesencephalic haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63:382–384.

14 Rinkel GJ, Wijdicks EF, Vermeulen M, et al. The clinical course of perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 1991;29:463–468.

15 Nibbelink DW, Torner JC, Henderson WG. Intracranial aneurysms and subarachnoid hemorrhage—report on a randomized treatment study. IV-A. Regulated bed rest. Stroke. 1977;8:202–218.

16 Suarez JI, Tarr RW, Selman WR. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:387–396.

17 Molyneux AJ, Kerr RSC, Yu L, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005;366:809–817.

18 Kassell NF, Torner JC, Haley EC, et al. The International Cooperative Study on the Timing of Aneurysm Surgery. Part 1: overall management results. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:18–36.

19 Challa PK, Smith KM, Conti CR. Initial presenting electrocardiogram as determinant for hospital admission in patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain: a pilot investigation. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30:558–561.

20 Christenson J, Innes G, McKnight D, et al. A clinical prediction rule for early discharge of patients with chest pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:1–10.

21 Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, et al. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1163–1170.

22 Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Bluemke DA, et al. Testing of low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:1756–1776.

23 . BestBets: The first ECG has a low sensitivity for myocardial infarction in patients with chest pain [Internet]. Date unknown. Cited Jan 30, 2011. Available at http://www.bestbets.org/bets/bet.php?id=75

24 Forest RS, Shofer FS, Sease KL, et al. Assessment of the standardized reporting guidelines ECG classification system: the presenting ECG predicts 30-day outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:206–212.

25 Hamm CW, Goldmann BU, Heeschen C, et al. Emergency room triage of patients with acute chest pain by means of rapid testing for cardiac troponin T or troponin I. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1648–1653.

26 Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non–ST elevation MI: a method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000;284:835–842.

27 Chase M, Robey JL, Zogby KE, et al. Prospective validation of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction risk score in the emergency department chest pain population. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:252–259.

28 Hoenig MR, Aroney CN, Scott IA. Early invasive versus conservative strategies for unstable angina and non–ST elevation myocardial infarction in the stent era. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2010. CD004815

29 Campbell CF, Chang AM, Sease KL, et al. Combining Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction risk score and clear-cut alternative diagnosis for chest pain risk stratification. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:37–42.

30 Ramsay G, Podogrodzka M, McClure C, et al. Risk prediction in patients presenting with suspected cardiac pain: the GRACE and TIMI risk scores versus clinical evaluation. QJM. 2007;100:11–18.

31 Tong KL, Kaul S, Wang X, et al. Myocardial contrast echocardiography versus Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction score in patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain and a nondiagnostic electrocardiogram. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:920–927.