Chapter 8 Medicare and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

INTRODUCTION — THE HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

Any health care system will have an impact on the wider social system. Medicare, Australia’s national health insurance scheme, is designed to ensure that all persons have equal access to care in a public health system. This means that all Australians have a stake in ensuring that the public health system functions effectively and thus Medicare can be seen as contributing to social cohesion and solidarity.

The following are the main features of Australia’s health system:[1]

THE PHARMACEUTICAL AND REPATRIATION PHARMACEUTICAL BENEFITS SCHEMES

The PBS and the RPBS are key components of the Australian health system, facilitating access to a large number of prescribed medicines through government subsidy of the cost. They form an integral part of Australia’s National Medicines Policy 2000 and the implementation of quality use of medicines as discussed in Chapter 2.

The PBS provides Australian residents, and eligible overseas visitors from countries with whom Australia has a reciprocal health care agreement, with subsidised access to approved medicines at an affordable price. At the time of writing reciprocal agreements were in place with nine countries, namely: Finland; Italy; Malta; New Zealand; Norway; Republic of Ireland; Sweden; the Netherlands; and the United Kingdom. The medicines are funded, either partially or wholly, by the Commonwealth Government. The PBS is regulated by the National Health (Pharmaceutical Benefits) Regulations 1960 (Cth), under Part VII of the National Health Act 1953 (Cth). The National Health Act 1953 (Cth) applies to the provision of pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, and of medical and dental services in Australia. Ministerial determinations and rules that apply to the PBS are periodically released to address specific issues.

Both the PBS and RPBS are administered by Medicare Australia.

HISTORY OF THE PBS AND RPBS

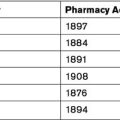

The following is a very brief overview of the history of the PBS and RPBS, with more detailed information available through the Parliamentary library.[2] The RPBS was established in 1919 for war veterans. A similar scheme for non-veterans was proposed in 1944 through the passing of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Act 1944 (Cth). However, the Australian Branch of the British Medical Association challenged the Act and the High Court declared the Act unconstitutional as its provisions went beyond the powers of the Commonwealth.

Listing steps

The PBAC considers submissions from industry sponsors, manufacturers, medical bodies, health professionals, private individuals and their representatives. The PBAC makes recommendations and gives advice to the Federal Minister for Health about which medicines should be made available as pharmaceutical benefits, the maximum quantities and repeats, and may also recommend restrictions. Box 8.1 lists the main roles of the PBAC.[3]

Box 8.1 Roles of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee

Under the National Health Act 1953 (Cth), the PBAC established two sub-committees to help perform its functions. These are the Drugs Utilisation Sub-Committee (DUSC) and the Economics Sub-Committee (ESC). The DUSC was formed by the PBAC in 1988 and monitors the patterns and trends of medicines used through the PBS. The ESC was formed by the PBAC in 1994 and advises on both cost-effective policies and evaluations of cost-effective aspects of major submissions.

Listed medicines are classified as either:

Public Summary Documents (PSDs) are published following PBAC meetings to improve the transparency of the listing process. These documents provide information about recommendations so that stakeholders are aware of the rationale for specific recommendations and gain an improved understanding of the overall PBS listing process. The availability of PSDs is the result of initiatives under the Australian–United States Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA). In a further attempt to increase transparency, the release of PBAC agendas in advance of meetings was introduced mid-2008.

The schedules

Three categories of benefits apply, namely:

Some items are listed for more than one condition and more than one type of benefit may apply.

A palliative care section provides for increased repeats of certain medicines for palliative care patients. A palliative care patient is defined as ‘A patient with an active, progressive, far-advanced disease for whom the prognosis is limited and the focus of care is the quality of life’.[4]

Section 100 programs

PBS AND RPBS PRESCRIBING

New rules were introduced in November 2008 to enable prescribers to write repeat prescriptions for up to 12 months for certain medicines subject to certain criteria being met. The criteria for prescribing under this ruling are that the patient has a stable chronic condition and is under the care of a general practitioner and continues to have regular reviews.

DISPENSING PBS AND RPBS PRESCRIPTIONS

Community pharmacies are the principal means, under current health service delivery arrangements through the PBS and RPBS, by which patients are able to access prescribed medicines. The dispensing of PBS and RPBS medicines is therefore one of the main responsibilities in pharmacy practice.

Non-PBS/RPBS prescriptions cannot be supplied under the PBS/RPBS and must be supplied as a private prescription where the patient is liable for the full cost of the medicine.

PATIENT CONTRIBUTIONS AND SUBSTITUTION

For a generic medicine to be listed on the PBS or RPBS, a manufacturer must demonstrate that their product is bioequivalent to the original brand.[6] The responsibility to ensure bioequivalence of generic medicines in Australia therefore lies with the pharmaceutical companies and the TGA. Two medicines are considered bioequivalent when they produce such similar plasma concentrations of the active ingredient that their clinical effects can be expected to be the same.[7] Bioequivalence is usually assessed in a small number of healthy volunteers through administering the two products on separate occasions. The peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and the extent of absorption, represented by the area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) of the generic medicine are then compared with that of the original brand. To be bioequivalent, the 90% confidence intervals (CI) for the ratio of each pharmacokinetic variable must lie between 0.80 and 1.25. This is a numerical index that provides an indication of the certainty of the study results.[8] The amount of active ingredient in the systemic circulation is hence used as a measure of the medicine’s clinical efficacy. Generic medicines must adhere to the same quality of manufacturing codes as branded medicines.[9]

Substitution by pharmacists without reference to the prescriber is permitted where:

There has been increased support by the Australian Government towards the use of generic medicines in an attempt to contain the growth of the PBS and RPBS budgets. These included amendments to the National Health (Pharmaceutical Benefits) Regulations 1960 (Cth) to promote increased generic prescribing. The changes required, as of February 2003, that computer prescribing programs must by default permit brand substitution for PBS prescriptions.[10]

PBS REFORMS

Significant PBS reforms were announced by the government in November 2006 and were introduced in July 2007 following the passing of the National Health Amendment (Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme) Act 2007 (Cth) (No 111, 2007). These changes were made to ensure the PBS remains affordable to the Australian Government, enabling it to continue to provide Australians with access to cost-effective medicines. The specific aim of the reforms was:[11]

F1 medicines are medicines where there is only a single brand listed. F1 medicines are not substitutable whereas F2 medicines are those where there are many brands listed. The amount that the government pays for F2 medicines was reduced through a complicated formulary that will undergo ongoing review.

The reforms also involve an increased push towards generic dispensing and the introduction of financial incentives for pharmacists to dispense generic products when available. This involves the payment of an additional $1.50 to a pharmacist when they dispense a generic medicine.[12] Through this incentive scheme, pharmacists are strongly encouraged to dispense generic medicines.

COMMUNITY PHARMACY AGREEMENTS

These programs and the associated incentive and remuneration structures represent a conceptual shift at policy level towards the payment for pharmacist professional services. They also create certain challenges for community pharmacists, including changing their practice to enable delivery of these professional services in a financially sustainable model.[13] There is a need to identify strategies that will enable the incorporation of these new professional services into everyday practice.

The newer professional services not only provide pharmacists with the opportunity to expand business practices, but also potentially result in an expansion in legal liability. There is therefore an increased need for the profession to remain abreast of professional developments. As stated by Coppock, ‘… any involvement in the delivery of new services requires careful analysis of the risk factors and strategies to minimise them’.[14]

THE IMPACT OF THE PBS ON PHARMACY PRACTICE

The PBS determines the dispensing fees that pharmacists receive and is a major determinant of their income. PBS compliance requirements have increased over recent years, with PBS dispensing requiring pharmacists to be up-to-date and vigilant regarding a range of complex PBS rules. PBS dispensing also places additional administrative demands on pharmacists. For example, obtaining concession card and Medicare card details, participating in PBS online, the 20-day/4-day rule and Brand Price Premiums. These can deflect pharmacists’ attention away from focusing on therapeutic issues and the provision of patient care during dispensing. Although many of the PBS administrative functions can be delegated to pharmacy support staff, compliance with PBS requirements still places additional burdens on pharmacists. Pharmacists therefore need to be innovative with regard to practice processes in order to minimise the time spent on administrative PBS issues.

Since its inception the PBS has been extended to include access to PBS medicines when a person is admitted to a private hospital or a residential aged care facility (RACF). However, the regulatory and administrative requirements of the PBS do not reflect these unique settings. For example, pharmacists providing services to RACFs are often asked to supply ongoing medicines before the doctor’s visit. This can place the pharmacist in a difficult position of needing to, on the one hand, comply with state and territory legislation and PBS requirements regarding verbal prescriptions. On the other hand, should pharmacists supply the medicines, they carry a risk of not getting paid for supplying the benefit if they do not get the prescription within the required time period. There are more scenarios unique to RACFs and private hospitals that currently make it difficult for pharmacists to provide best patient care while still complying with PBS requirements. A review has therefore been commissioned to undertake a re-evaluation of the PBS supply arrangements in the context of RACFs and private hospitals.[15]

HEALTH INSURANCE ACT 1973 (CTH)

The Health Insurance Act 1973 (Cth) established a government scheme of entitlements, for payment for health services provided to eligible Australian residents. This national health insurance system, known as Medicare, was introduced in 1984 and, until October 2005, was administered by the Health Insurance Commission. Under the Health Services Legislation Amendment Act 2005, the Health Insurance Commission became Medicare Australia which now administers a number of health programs,[16] manages claim processing and arranges payments of benefits for Medicare, including PBS and the RPBS.

The Medicare system is funded from Australian taxation monies and is based on the premise that all Australians should contribute to their own health care according to their ability to pay. Some of the health services included within the scheme under the provisions of the Health Insurance Act 1973 are medical, pathology, diagnostic imaging and radiation oncology. Medicare therefore provides free, or subsidised, access to treatment for public patients in public health care facilities, or through the private sector. Patients undergoing specified dental treatments or treatment by participating optometrists may also be eligible to receive a government contribution through the Medicare system. Medicare benefits and entitlements are fixed by reference to a table of items in the Schedule of fees set by the Australian Government.

A provider identified within the categories contained within the Health Insurance Act 1973 must have a Medicare provider number for their patients to be eligible for the reimbursement. Medicare Australia issues and records the details of those health professionals to whom provider numbers are issued. Provider numbers are now specific to the purpose or service rendered. A provider number allows the health professional to raise referrals to specialist services, request pathology or diagnostic imaging and obtain a Medicare rebate for their own professional service. All medical practitioners with Australian medical registration can obtain a provider number, which enables them to prescribe pharmaceuticals.

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme website: www.pbs.gov.au

De Vries J., Gleave D., Best J., et al. Generic medicines: dealing with multiple brands. National Prescribing Service News. December 2007;55:1-4.

Department of Health and Ageing. Fact sheet: Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) reform. 2007. Online. Available: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/24693658DD49E286CA2572750081DB74/$File/PBS%20Reform%202Feb07.pdf

1 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Health expenditure Australia 2006–7. Canberra: AIHW; September 2008.

2 Biggs A. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme — an overview. 2 January 2003. Online. Available: www.aph.gov.au/library/INTGUIDE/SP/pbs.htm [accessed 21 November 2008]

3 Department of Health and Ageing. For Industry. Role of the pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committe. 2008. Online. Available: www.pbs.gov.au/html/industry/static/how_to_list_on_the_pbs/elements_of_the_listing_process/pbac_guidelines/a_part_1/section_1 [accessed 13 October 2008]

4 Department of Health and Ageing. Preparations which may be prescribed for patients receiving palliative care. 2008. Online. Available: www.pbs.gov.au/html/healthpro/browseby/palliative-care [accessed 25 October 2008]

5 The PBS Safety Net scheme was launched in 1986 to help individuals and families with high prescription medicine costs. Each year the government sets two Safety Net thresholds, namely one for general patients and one for people who have a concession card. When the patient or family reaches their relevant threshold, they are eligible to apply for a Safety Net card to receive PBS medicine either cheaper or free for the rest of the calendar year. Individuals and families hence need to keep a Prescription Record Form (PRF), listing all the PBS medicines supplied, to be used to determine when the Safety Net would apply

6 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian regulatory guidelines for prescription medicines (ARGPM). 2004. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/pmeds/argpm.htm [accessed 16 June 2008]

7 De Vries J., Gleave D., Best J., et al. Generic medicines: dealing with multiple brands. National Prescribing Service News. December 2007;55:1-4.

8 Pearce G.A., McLachlan A., Ramzan I. Bioequivalence: How, why, and what does it really mean? Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research. 2004;34(3):195-200.

9 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian code of good manufacturing practice for medicinal products. 2002. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/docs/html/gmpeodau.htm [accessed 16 June 2008]

10 Lockney A. Generic medicines. inPHARMation. June 2003:6-10.

11 See the Hon. Tony Abbott MfHaA. ‘PBS Reform’ media release. In: Department of Health and Ageing C, ed. 16 November 2006

12 Department of Health and Ageing. Fact sheet: Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) reform. 2007. Online. Available: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/24693658DD49E286CA2572750081DB74/$File/PBS%20Reform%202Feb07.pdf [accessed 18 June 2008]

13 Roberts A, Benrimoj S, Chen T, Williams K, Aslani P. Qualification of facilitators to accelerate uptake of cognitive pharmaceutical services (CPS) in community pharmacy. August 2004. Online. Available: www.guild.org.au/research/project_display.asp?id=263 [accessed 9 March 2006]

14 Coppock J. Careful collaboration reduces patient risks. Australian Journal of Pharmacy. July 2005;86:498.

15 Health Management Advisors. Review of the existing supply arrangements of PBS medicines in residential aged care facilities and private hospitals. Discussion paper: Part A — The review context and process. An invitation to make submissions by Wednesday 21 January 2009.

16 On behalf of the Department of Health and Ageing, Department of Veteran Affairs, Department of Families and Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and the Department of Health Western Australia.