CHAPTER 90 Medical Rehabilitation – Lumbar Axial Pain

INTRODUCTION

Axial low back pain is a common complaint of patients visiting physicians who practice musculoskeletal and pain medicine. The majority of these patients are diagnosed with non-specific back pain, which is presumed to be caused by muscle or ligament soft tissue damage, while many of these patients will actually have pain associated to injury to the posterior elements or the disc. These patients are thought to have a good prognosis for recovery; they improve in 4–12 weeks after the onset of pain, and the strategies of treatment used focus only on short-term management. In reality, many of these patients have future episodes of back pain associated with recurrent injury to the disc and associated structures and some will present with chronic back pain. Patients with unresolved pain may develop significant changes in the quality of their life including reduced health perception, happiness, social participation, and restriction of function.1 In addition, significant direct and indirect healthcare costs are associated with chronic low back pain.2

The overwhelming majority of patients with back pain will not require surgery and should be managed with conservative treatments which include rehabilitation and functional restoration.3–5 The goals of rehabilitation are to return the individual with low back pain to normal function. This requires achieving control of pain, adequate flexibility, strength, and muscle balance as well as neuromuscular coordination that would allow the return to normal activities. Evaluation, management, and rehabilitation of low back pain also require that the clinician understands the vocational and avocational demands of the patients and their goals.

FACTORS INFLUENCING REHABILITATION

Epidemiology

The annual incidence of low back pain in the general population is 5%, with many patients presenting between the ages of 30 and 50 years, and a significant number of cases resolving within 4 weeks of presentation. Of these patients, particularly the ones who present with pain at an early age, a significant number will present with recurrence of the symptoms, and some will develop chronic disability. Therefore, a functional rehabilitation program should be instituted early in the disease process.6–8

Some individual risk factors for pain are modifiable and include obesity, cigarette smoking, and low fitness level.9,10 Occupational factors associated with back pain include vibration, static work posture, flexed posture, frequent bending and twisting, lifting and material handling.11,12 Psychosocial factors associated with back pain and recurrence of symptoms include dissatisfaction with work, long duration of initial treatment, recurrent treatment, and being disabled from work.13–15 Other factors, such as heredity, may not be modifiable but also play a role in the development of low back pain. Familial predisposition to back pain and degenerative disc disease has been described and may be important in patients who present at an early age (Table 90.1).16–19

| Epidemiologic Evidence | |

|---|---|

| Individual/Intrinsic | External/Extrinsic |

| Age | Static work postures |

| Gender | Prolonged sitting |

| Abdominal girth | Frequent lifting, pushing and pulling |

| Smoking | Frequent trunk rotation |

| Muscle weakness/loss of endurance | Vibration exposure |

| Reduced/excessive flexibility | Repeated lumbar flexion |

| Sedentary life style | Activity early in the day |

Sports and recreational activities are also associated with the development of back pain, wherein 10–15% of all sports injuries are related to the spine. Rotational, torsional, and compressive stresses to the spine are associated with the development of intrinsic disc disease.20,21 Activities in daily life that involve frequent bending and lifting may also lead to back pain. Individuals caring for elderly or disabled family members present with an increased prevalence of back pain.22

Functional anatomy and biomechanics

A review of the anatomy and biomechanics of the spine is beyond the scope of this chapter; however, an understanding of the functional anatomy as well as basic concepts of biomechanics of the lumbar spine is important for the clinician who treats and rehabilitates patients with low back pain.

The basic functional unit of the lumbar spine is the three-joint complex formed by two consecutive vertebra, the intervertebral disc, and the zygapophyseal joints. The anterior elements of the lumbar spine sustain the compression loads applied to the vertebral column including body weight and loads associated with contraction of the back muscles. The posterior elements regulate the passive and active forces applied to the vertebral column and regulate motion. The zygapophyseal joints are typical synovial joints endowed with cartilage, capsule, meniscoids, and synovial membrane. The articular facets exhibit variations in both the shape of their articular surfaces and their orientation. In the lumbar spine the only movement permitted is a sliding motion in a vertical direction, executed during flexion and extension.23

Muscle function is very important for the lumbar spine since ligaments provide little static stability and in the absence of muscle activity the spine could buckle with low compressive loads. The erector spinae are composed of two major groups: the longissimus and iliocostalis. They are primarily thoracic muscles that act on the lumbar spine with a long moment arm ideal for lumbar spine extension. The small rotatores and intertransversarii muscles are basically length transducers and position sensors. The multifidi which cross 2 or 3 segmental levels are theorized to work as spinal stabilizers.24

Other muscle groups important for low back function are the quadratus lumborum, which has a direct insertion in the lumbar spine and acts as a weak lateral flexor, and the abdominal muscles which include: the transversus abdominus, internal and external oblique, and rectus abdominus. These muscles are important in flexion of the trunk, lateral bending, but most importantly help to stabilize the lumbar spine. Pelvic muscles also play a role in the kinetic chain by acting on the lumbar spine and transmitting forces from the lower extremity to the trunk and upper extremities and include: the hip flexors such as the iliopsoas, and gluteal hip extensor, as well as abductor muscles.25

Pathophysiology of injury

Flexion of the lumbar spine, which involves sagittal rotation and translation, is well tolerated by the lumbar elements. Compression of the lumbar spine occurs by adding body weight, muscular contraction, and the loads that are lifted by the individual. Excessive compression may injure the anterior vertebral elements, particularly the endplates. When flexion and compression are combined with rotation, shear applied to the intervertebral disc results in injury to this structure. Vertebral extension is limited primarily by bony impaction of the spinal processes or the inferior articular facet against the lamina below, and repeated extension as well as rotation activities may lead to injury of the posterior elements such as the pars intercularis.26

Lumbar disc disease associated with axial back pain is multifactorial in origin. Aging, apoptosis, abnormalities in collagen, vascular ingrowth, loads placed on the disc, and abnormal proteoglycan all contribute to disc degeneration.27 Repetitive or continuous axial overloading, associated with disc fatigue, is key in the pathogenesis of lumbosacral degenerative disease.24 Vigorous occupational activity and competitive athletic participation associated with end-range flexion and frequent turning predispose the disc to herniation and accelerated degeneration.28

These changes in the disc, which progress from herniation to subsequent internal disruption and resorption, may affect more than one functional unit and compromise spinal motion. The combined changes in the posterior joint and discs lead to arthritis, lateral recess stenosis, and central stenosis.29–31

Low back pain may result from compression of nerve tissue, inflammation of the nerve root, and the facet joint, as well as damage to the anulus fibrosus. Inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins and substance P, have been identified in patients with disc disease and are associated with pain in the absence of a compressive lesion.28,32

Increasing age has been associated with progressive disc degeneration which can be asymptomatic in some individuals. Changes in trabecular bone morphology and inappropriate disc matrix may be related to apoptosis, or programmed cell death, in the patient with disc disease.27,33

Clinical presentation

In the individual with axial back pain, the history and physical examination are very important in the planning of a functional rehabilitation program. Pertinent information that should be obtained from the history include: the type of pain, the mechanism of injury, exacerbating and mitigating factors, and previous injuries and response to treatment strategies. The physical examination should identify limitations of motion, direction of pain exacerbation, lack of flexibility, muscle weakness and imbalance, ligamentous laxity, and neurologic as well as proprioceptive deficits. This information combined with pain diagrams, diagnostic imaging, and injection procedures allows the clinician to recognize specific characteristics of different clinical subsets.34 Clinical subsets of axial back pain include patients with acute annular tears, intrinsic disc disease, facet joint degeneration, or posterior element injury.

The patient with chronic discogenic disease will present with axial back pain, intolerance to sitting as well as pain upon arising from a chair, limited capability to lift, bend, or twist.35 Physical examination will reveal soft tissue inflexibility of paravertebral muscles, fascia and ligaments as well as some muscle spasm. There may be evidence of lumbar segmental hypomobility, loss of lumbar lordosis, and pain with flexion and rotation. The neurologic examination is usually normal with no evidence of root irritation.36 Individuals who present with an acute on chronic injury give the history of an excessive load or sudden trauma superimposed on previous discogenic symptoms. The physical examination is usually similar to patients that presents with an acute annular tear.

Patients who present with axial back pain may also have involvement of posterior elements such as the facet joints. These individuals may present with pain in the back which may radiate to the buttocks or thighs that could worsen with extension activities such as walking downhill, prone lying, and prolonged standing. Other patients may present with a different history such as pain with flexion that is not exacerbated by sitting and still have facet joint pathology. The physical examination may reveal inflexibility of the lumbar soft tissues, hypomobility of spine segments, and pain with extension or flexion as well as rotation maneuvers. The neurologic examination and special maneuvers to identify root irritation are usually normal, and injection procedures may be required to clearly identify the facet joint as the pain generator.37

In sports, the patterns of back injury will depend on several factors which include the patient’s age and sport-specific demands. Athletes involved in sports that require trunk rotation and hyperextension usually present with axial back pain associated to posterior element injury. Repeated stresses associated to gymnastics, diving, and wrestling places the athlete at increased risk of pars interarticularis injury such as spondylolisis. These athletes may present with acute or gradual onset of pain and limited motion which restricts activity.38

Older individuals who exercise vigorously or participate in sports will generally present with injuries of the vertebral endplate and the intervertebral discs. These individuals usually present with symptoms associated to repeated flexion and trunk rotation. They may present with episodes of axial back pain and limited motion which may be accompanied by leg symptoms.39

Psychosocial factors

Psychologic and social issues should be addressed in the individual with axial back pain because they may affect rehabilitation, and include coexisting anxiety, depression, family or work related stress, and lack of social support. Work dissatisfaction, fear of recurrence of pain with activity, and pending compensation are also factors that may be impediments to return to normal activity.14

BASIC CONCEPTS OF REHABILITATION

Complete diagnosis of musculoskeletal injury

Prior to starting rehabilitation, attempts should be made to reach a complete diagnosis of the patient with back pain including the pain generator and the biomechanical deficits. In the authors’ practice, a modification of the musculoskeletal injury model described by Kibler is used for this purpose. This model identifies the anatomic site of injury, the clinical symptoms, and the functional deficits (Table 90.2).40

| Axial Back Pain | |

|---|---|

| CLINICAL ATERATIONS | |

| Symptoms | |

| Back pain | |

| Sitting intolerance | |

| Pain with bending | |

| ANATOMIC ALTERATIONS | |

| Tissue injuries: vertebral end plate, intervertebral disc, facet joints | |

| Tissue overload: extensor muscles, interspinal ligaments | |

| FUNCTIONAL ALTERATIONS | |

| Biomechanical deficits: weak back extensors, tight hip flexors | |

| Adaptive behavior: avoidance of trunk flexion, rotation, prolonged sitting | |

Phases of rehabilitation

Musculoskeletal rehabilitation combines therapeutic modalities and exercise in order to return the individual to normal function. It should start early in the disease process in order to reduce the deleterious effects of inactivity and immobilization. A medical rehabilitation program should state the goals and objectives of treatment specific for each phase of rehabilitation. The treatment should focus on optimizing the healing process, restoring the biomechanical relations between the normal and injured tissue, and finally preventing recurrence of pain and chronic disability. A functional rehabilitation program emphasizes therapeutic exercise and physical activity while monitoring for exacerbation of symptoms. Rehabilitation of the patient with back pain can be divided into acute, recovery, and functional phases (Table 90.3).

Table 90.3 Goals in Rehabilitation of Musculoskeletal Injury

| Acute Phase | Recovery Phase | Functional Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Treat clinical symptoms | Allow tissue healing | Correct abnormal biomechanics |

| Protect injured tissue | Restore normal strength and flexibility | Prevent recurrent injury |

The functional or maintenance phase should focus on increasing power and endurance while improving neuromuscular control. Rehabilitation at this stage should work on the entire kinematic chain, addressing specific residual functional deficits. The individual should be pain free, exhibit full range of motion, normal strength, and muscle balance prior to returning to full activity.

REHABILITATION OF AXIAL BACK PAIN

The functional rehabilitation model of patient management should be implemented as soon as the patient presents for clinical evaluation of back pain. As previously discussed, identification of the pain generator should be attempted based on the information obtained from the history, physical examination, laboratory studies, imaging data, and diagnostic injections.41 However, in many instances, the pain generator cannot be definitely identified, and a functional approach to the rehabilitation should be undertaken after developing a working diagnosis. Patterns of pain provocation with motion, muscle weakness, inflexibility, abnormal biomechanics, and functional abnormalities can be identified, used as a starting point for treatment, and addressed in a progressive manner.

Acute phase

The acute phase of treatment is the period when pain should be addressed, and the injured tissue should be protected from further damage, with the purpose of optimizing the healing process and allowing the patient to progress in the rehabilitation program. It is important to understand that a balance must be achieved between treating the pain with medications, among other passive rehabilitation therapeutic interventions, and encouraging active patient participation in their treatment early in the recovery process (Table 90.4).

There are multiple clinical studies that show evidence that prescription of various types of NSAIDs at regular intervals provides effective pain relief from acute low back pain.42–45 Use of over-the-counter nonselective NSAIDs can be an initial treatment option, particularly for young patients without a history of gastrointestinal problems.46 In patients with a history of gastrointestinal problems, elderly individuals, or those patients in whom less frequent dosing is important for compliance, COX-2-specific inhibitors offer a therapeutic alternative.47,48 Risk of cardiovascular disease and monitoring fluid retention, blood pressure, and renal and liver function is important for any patient being treated with NSAIDs but particularly those treated with COX-2 inhibitors.

In addition, there is clinical and scientific evidence that the different types of muscle relaxants are equally effective in the management of acute low back pain.49–51 However, muscle relaxants have significant adverse effects, such as drowsiness, risk of habituation, and dependency, which require that they be used with caution. The use of low-dose regimens of muscle relaxants offer a good therapeutic alternative with reduced side effects and similar efficacy.52 In many patients, low-dose muscle relaxants are used for a short period of time, particularly at night in patients with sleep dysfunction, since they may aid in sleep. Another treatment alternative to consider in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic symptoms and sleep dysfunction associated with fatigue is antidepressant medications, particularly the tricyclic agents because of their anticholinergic sedative and analgesic effects.53

During the acute phase, the focus is on reducing pain and protecting injured or inflamed tissue. A common therapeutic intervention in the acute phase of rehabilitation is restricted activity and bed rest. At present, there is scientific evidence that prolonged bed rest is not effective and may be detrimental for patients with acute low back pain.54,55 Based on the best information available, bed rest should be kept to less than 2–3 days for nonradicular low back pain. Hagen et al., from the Cochrane Collaborative Group, reviewed nine clinical trials in which bed rest was used in patients with acute back pain and sciatica and concluded that there is not an important difference in the effects of bed rest when compared to exercise in this patient population and that prolonged bed rest does not appear to be indicated even in the case of sciatica.55

Hilde and colleagues, from the same Cochrane Collaborative Group, reviewed four clinical trials with a total of 491 patients in which advice to stay active was included as a treatment strategy and concluded that the best available scientific evidence suggests that physical activity has a beneficial effect for patients with acute low back pain.56 In the authors’ clinical practice, low-intensity aerobic exercise is routinely prescribed for patients with acute back pain. Walking or swimming are appropriate exercises to prescribe for patients with discogenic pain, while bicycling is adequate for those with posterior element injury.

Patient education is very important and should start in the acute phase of rehabilitation. Individuals participating in the rehabilitation program should be educated in the basic concepts of the pathophysiology of their illness, patterns of back pain, and proper spine biomechanics. The patient should be oriented on how to identify changes of intensity, frequency, and duration of pain patterns, how they affect their rehabilitation, and how their medication should be taken. In addition, strategies that allow the patient to cope with their pain are important and should be established early in the management process. The identification of barriers to recovery such as beliefs about the harm of physical activity, comorbid factors such as psychiatric illness, job dissatisfaction, and unemployment is important to prevent the progression to chronic pain.57–59

Physical modalities such as cryotherapy are frequently used in combination with prescribed analgesics at regular intervals. Although the physiologic effects of cold include analgesia, reduction of inflammation, and muscle spasm, making cryotherapy ideal for treatment for acute injury, there is no strong evidence in the medical literature for their benefits in the management of acute back pain.28,60,61 Standard physical therapy treatment has not been shown to be effective in changing long-term outcome of patients with back pain; however, there is a patient-perceived benefit from such treatment.62 It is the authors’ clinical experience that short-term supervised physical therapy early in the clinical course of patients with acute back pain allows a more rapid progression and transition to an activity program, and it is frequently recommended to their patients.

Muscle weakness, inhibition, and imbalance particularly of trunk muscles is commonly seen in patients who present with acute or recurrent back pain. Isometric and static exercises should be initiated to retrain proper muscle firing patterns in patients with muscle inhibition and abnormal firing patterns. Identification of the neutral spine position for stabilization exercises is very important at this stage since spine stability is necessary prior to achieving mobility in exercise, work, and activities of daily living. Gradual pain-free range of motion exercises for the back, hips, and lower extremities should be instituted in the acute management. Although, these exercises are commonly used and reported to have good clinical results, there is conflicting scientific evidence that specific back exercises such as flexion, extension, or stretching produce symptomatic improvement in acute low back pain.63

Another modality often recommended in this phase of treatment is electrical stimulation for pain control. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for analgesia has been used in the past by many clinicians treating acute back injury based on the physiologic effects of this modality, which is theorized to block pain perception at the level of the spinal cord and may also cause secretion of endogenous opioids.64 However, there is conflicting evidence for the effectiveness of these treatments in acute back pain, and recent data suggest that subthreshold TENS is not effective treatment for low back pain.65,66 There are additional data that electro-acupuncture is more effective than TENS and classic massage, particularly if indicated in combination with back exercises. This can be an effective option for the treatment of pain and disability associated with chronic low back pain.67

Recovery phase

The recovery phase of treatment is the subacute period that focuses on restoring the biomechanical relations between the normal and injured tissue (Table 90.5). Patients should be advised to gradually increase their physical activity in daily living despite the existence of some pain.

Physical modalities such as superficial heat, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation are commonly recommended for treatment of pain in the recovery phase. There is limited evidence in the scientific literature that selected modalities in isolation are effective in this phase of treatment; however, based on their physiologic effects of analgesia, reduction of muscle spasm, facilitation of muscle recruitment, and increased distensibility of soft tissue, they are used in the authors’ practice for a limited period of time in combination with therapeutic exercises such as flexibility training and dynamic strengthening.28,68

Massage and manipulation have been used extensively and are thought to be effective in acute pain when combined with exercises and education. However, Assendelft et al. reviewed randomized clinical trials of spinal manipulation for the treatment of low back pain and concluded that there is no scientific evidence that spinal manipulation therapy is superior to other standard or conventional modalities of treatment for pain relief in patients with acute low back pain.69 The medical literature is not clear and gives conflicting evidence for the use of spinal manipulation for exacerbations of pain or chronic pain, with some studies reporting good short-term results in acute exacerbations.70–72 In the authors’ practice, patients with acute pain or exacerbation of baseline chronic symptoms are referred for manual therapy with good subjective results of pain reduction and increased mobility.

In the recovery phase, flexion- or extension-biased exercise should be prescribed based on the identification of the direction that exacerbates the symptoms. The McKenzie approach uses a mechanical assessment of the patient to identify direction of pain exacerbation and has been advocated by many clinicians. The centralization phenomenon or the reduction of pain with preferential direction of motion has been associated with good prognosis for recovery.73 Patients with axial pain secondary to discogenic disease may benefit from extension exercises while patients with posterior element or facet syndrome may benefit from flexion exercises.74 Care should be taken when exercising patients to extreme ranges of motion, since these positions may increase the compressive load to the intervertebral discs.24 There is some evidence that exercises may be effective for patients in the subacute or chronic stage of treatment and may slightly reduce the risk of additional back problems or work disability.75 The intensity of the exercises should be monitored, increased gradually depending on the clinical response, with a specific prescription, and in some instances even in the presence of some pain.76,77

Strengthening of the core musculature has become important in the rehabilitation of patients with back pain. The muscles that are targeted for exercise training include the multifidi, quadratus lumborum, abdominals, and hip girdle muscles. Back stabilization exercises in the neutral spine position are used to initiate strengthening of the back and pelvic core musculature. McGill and others have looked at exercises that could be safely used for strengthening in patients with back pain and these include the curl-up, side bridge, and bird dog or quadruped exercise. Endurance training with a high number of exercise repetitions rather than high-resistance strength training should be emphasized in the patient with back pain at this stage.25,78,79

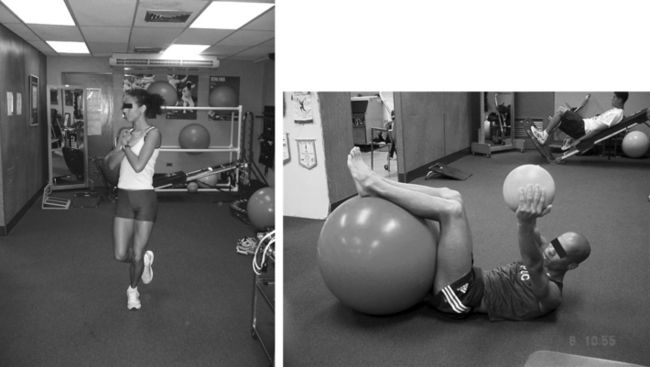

In the recovery phase, the stabilization program should progress in difficulty, moving from stable to unstable surfaces.80 As the patient’s symptoms improve, inflexibilities and muscle imbalances of specific muscles such as the hip rotators, iliopsoas, and hamstrings should be addressed. Dynamic flexibility training in sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes of motion should be started gradually (Fig. 90.1). Progression of the aerobic and conditioning program is continued during this phase.25

Analgesic and antiinflammatory medications can be prescribed at this point of the treatment program only to facilitate a gradual increase in activities, but should be prescribed for a fixed period of time. Opioid analgesics remain an alternative for patients with no relief from other medications and have been reported to increase back exercise performance in those with intolerance to exercise secondary to pain.81

Local injections and interventional techniques such as epidural, facet, and medial branch blocks or radiofrequency denervation could also be considered at this point in the rehabilitation of patients. When attempting higher levels of activity, symptomatic individuals may benefit from these procedures to control pain and allow participation in the exercise program.82,83 Special patient populations addressed with interventional procedures in this stage include athletes and individuals who need to return to heavy labor. It is the authors’ clinical goal to reduce the fear of activity in these patients.

Complementary medicine approaches to pain management which include acupuncture and relaxation techniques have also been used in this stage of rehabilitation; however, the effectiveness of these treatments in long-term management is not clear.84 The authors recommend using acupuncture to their chronic patients with acute exacerbations who show slow response to treatment, including integrating muscle relaxation and visualization techniques, who present with activity-related anxiety.

The functional phase of treatment emphasizes restoration of function for work and activities of daily living (Table 90.6). Another important objective of this phase of treatment is the prevention or reduction of physical or mental disability as well as improving the patient’s quality of life. The final goal is to prevent dependence on medical treatment and allow the patient the transition to exercising on his or her own. At this stage, patients with disabling low back problems who fail to progress in treatment should be referred to a multidisciplinary or behavioral pain management program.85,86 Factors that may predict the failure of an interdisciplinary program in returning the individuals to work include those patients involved in compensation claims and those with a subjective feeling of being disabled.87,88

Table 90.6 Rehabilitation of Back Injury – Functional Phase

Functional phase

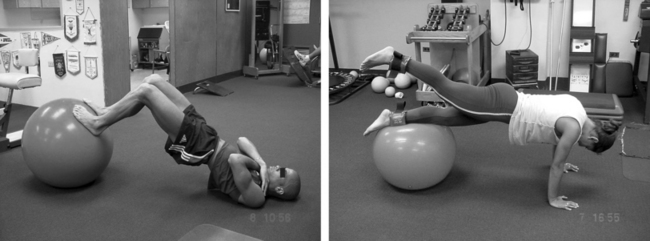

In the functional phase, progression of trunk strengthening is emphasized. Exercises with gym balls, rotational patterns, and eccentric loading of the spine are emphasized (Fig. 90.2). Rainville et al.77 and Cohen and Rainville89 have reported the use of aggressive quota-based exercise programs with the intent of reducing disability and altering fears about functional activities. Their results demonstrate that this is an effective treatment strategy in patients with chronic pain. Improvement in pain intensity and frequency, posture, self-efficacy with activity, and well-being, in addition to increased return to work status, have been documented 6 months to 1 year following rehabilitation.90–92 Finally, normal spine mechanics for sports and work activities and progression of functional training is required prior to allowing the athlete to return to competition or the individual to return to full activity.

Lumbar supports and braces have been used with the goal of preventing either the onset or recurrence of low back pain. However, the medical literature has not shown effectiveness for this intervention.93–95 In a rehabilitation program, lumbar supports may be used to provide short-term patient comfort, allow participation in an exercise program, and enhance trunk proprioceptive training.96 Special consideration should be given to the use of bracing in patients with axial back pain suspected of having spondylolisis.38

Interventional and injection techniques should also be considered in this stage of patient management. Butterman has used spinal steroid injections for degenerative disc disease in patients with chronic symptoms and acute exacerbations for temporary improvement in pain and function that allows return to activity.97 Zygapophyseal joint injections and radiofrequency denervation for the treatment of patients with zygapophyseal joint-mediated pain can also be considered in the functional phase. Sparse scientific evidence for the long-term effectiveness of these treatments has been evaluated by Slipman et al. in a critical review of the medical literature. However, these treatments remain viable options in the individual with posterior element symptoms and activity intolerance.98 Other techniques that are used for chronic low back pain and have gained recent acceptance include botulinum toxin injections and prolotherapy. Although these treatment are safe, with good anecdotal results when used for addressing the soft tissues as pain generators, there is no scientific evidence documenting their effectiveness in the treatment of chronic low back pain. More studies are required prior to recommending their widespread use.99–101

Another factor to be considered during the rehabilitation process is modification of activity and the work environment. Simple strategies such as establishing a standing rest period after sitting for 50 minutes to 1 hour has been shown to reduce the compressive load on the lumbar spine.102 In addition, avoidance of prolonged flexion and rotation activities during the rehabilitation process should be encouraged.

SUMMARY

Interventional techniques should be considered part of the rehabilitation armamentarium and integrated into the different stages of treatment. They should be used to reduce pain in the acute phase, to allow an increase in activity tolerance in the recovery phase, and finally to manage symptoms exacerbation in the functional phase of rehabilitation.

1 Takeyachi Y, Konno S, Otani K, et al. Correlation of low back pain with functional status, general health perception, social participation, subjective happiness and patient satisfaction. Spine. 2003;28(13):1461-1466.

2 Yelin E. Cost of musculoskeletal diseases: impact of work disability and functional decline. J Rheumatol (Suppl). 2003;68:8-11.

3 Atlas SJ, Nardin RA. Evaluation and treatment of low back pain: an evidence-based approach to clinical care. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27(3):265-284.

4 Lee D. Low back pain intervention: conservative or surgical? J Surg Orthop Adv. 2003;12(4):200-202.

5 Long DM. Decision making in lumbar disease. Clin Neurosurg. 1992;39:36-51.

6 Frymoyer JW, Cats-Baril WL. An overview of the incidences and costs of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991;22(2):263-271.

7 Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Y de C, Engberg M, et al. The course of low back pain in a general population. Results from a 5-year prospective study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26(4):213-219.

8 Salminen JJ, Erkintalo Mo, Pentti J, et al. Recurrent low back pain in early disc degeneration in the young. Spine. 1999;24(13):1316-1321.

9 Frymoyer JW, Pope MH, Clements JH, et al. Risk factors in low-back pain. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1983;65(2):213-218.

10 Cady LD, Bischoff DP, O’Connell ER, et al. Strength and fitness and subsequent back injuries in firefighters. J Occup Med. 1979;21:269-272.

11 Frymoyer JW. Lumbar disk disease: epidemiology. Instr Course Lect. 1992;41:217-223.

12 Biering-Sorensen F. A prospective study of low back pain in general population. ii Location, character, aggravating and relieving factors. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1983;15(2):81-88.

13 Borenstein DG. Epidemiology, etiology, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment of low back pain. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12(2):143-149.

14 Wasiak R, Verma S, Pransky G, et al. Risk factors for recurrent episodes of care and work disability: case of low back pain. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46(1):68-76.

15 Biering-Sorensen F. A prospective study of low back pain in a general population. ii Medical service-work consequence. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1983;15(2):89-96.

16 Hartvigsen J, Christensen K, Frederiksen H, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to back pain in old age: a study of 2,108 Danish twins aged 70 and older. Spine. 2004;29(8):897-901.

17 Simmons EDJr, Guntupalli M, Kowalski JM, et al. Familial predisposition for degenerative disc disease. a case control study. Spine. 1996;21(13):1527-1529.

18 Livshits G, Cohen Z, Higla O, et al. Familial history, age and smoking are important risk factors for disc degeneration disease in Arabic pedigrees. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17(7):643-651.

19 Pietila TA, Stendel R, Kombos T, et al. Lumbar disc herniation in patients up to 25 years of age. Neurol Med Chir. 2001;41(7):340-344.

20 Trainor TJ, Wiesel SW. Epidemiology of back pain in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21(1):93-103.

21 Cooke PM, Lutz GE. Internal disc disruption and axial back pain in the athlete. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2000;11(4):837-865.

22 Tong HC, Haig AJ, Nelson VS, et al. Low back pain in adult female caregivers of children with physical disabilities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(11):1128-1133.

23 Bogduk N. Anatomy and biomechanics. In: Cole A, Herring S, editors. Low back pain handbook: a guide for the practicing clinician. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2003:9-26.

24 McGill S. Low back disorders: evidence-based prevention and rehabilitation. Champain (IL): Human Kinetics, 2002.

25 Akuthota V, Nadler SF. Core strengthening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(S):S86-S92.

26 Bogduk N, Twomey LT. Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine. Melbourne: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

27 Martin MD, Boxell CM, Malone DG. Pathophysiology of lumbar disc degeneration: a review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus, 13(2);2002. Online Available: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/442440.

28 Rengachary SS, Balabhadra RS. Black disc disease: a commentary. Neurosurg Focus, 13(2);2002. Online Available: http://medscape.com/viewarticle/442455.

29 Van Dieen JH, Weinans H, Toussaint HM. Fractures of the lumbar vertebral endplate in the etiology of low back pain: a hypothesis on the causative role of spinal compression in a specific low back pain. Med Hypotheses. 1999;53(3):246-252.

30 Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Wedge JH, Young-Hing K, et al. Pathology and pathogenesis of lumbar spondylosis and stenosis. Spine. 1978;3(4):319-328.

31 Yong-Hing K, Kirkaldy-Willis WH. The pathophysiology of degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. Orthop Clin North Am. 1983;14(3):491-504.

32 Kirkaldy-Willis WH. The relationship of structural pathology to the nerve root. Spine. 1984;9(1):49-52.

33 Simpson EK, Parkinson IH, Manthey B, et al. Intervertebral disc disorganization is related to trabecular bone architecture in the lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(4):681-687.

34 Ohnmeiss D, Vahharanta H, Ekholm J. Relation between pain location and disc pathology: a study of pain drawing and CT/discography. Clin J Pain. 1999;15(13):210-217.

35 Young S, Aprill C, Laslett M. Correlation of clinical examination characteristics with three sources of chronic low back pain. Spine J. 2003;3(6):460-465.

36 Bernard TNJr, Kirkaldy-Willis WH. Recognizing specific characteristics of nonspecific low back pain. Clin Orthop. 1987;217:266-280.

37 Dreyer SJ, Dreyfuss PH. Low back pain and the zygapophyseal joints. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1996;77(3):290-300.

38 Gerbino PG, Micheli LJ. Low back injuries in the young athlete [review]. Sports Med Arthroscopy. 1996;4:122-131.

39 Young JL, Press JM, Herring SA. The disc at risk in athletes: perspectives on operative and nonoperative care. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(S):222-232.

40 Kibler WB. A framework for sports medicine. PMR Clin N Am. 1994;5:1-8.

41 Revel M, Poiraudeau S, Auleley GR, et al. Capacity of the clinical picture to characterize low back pain relieved by facet joint anesthesia. Proposed criteria to identify patients with painful facet joints. Spine. 1998;23(18):1972-1976.

42 Bahshe R, Thumb N, Broll H, et al. Treatment of acute lumbosacral back pain with piroxicam: result of a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Spine. 1987;12:473-476.

43 Hosie GAC. The topical NSAID, felbinac versus oral ibuprofen: a comparison of efficacy in the treatment of acute lower back injury. Br. Clin Res. 1993;4:5-17.

44 Spalski M, Hayez JP. Objective functional assessment of the efficacy of temoxican in the treatment of acute low back pain: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:74-78.

45 Poslacchini F, Facchini M, Paleire P. Efficacy of various forms of conservative treatment in low back pain: comparative study. Neurol Orthop. 1988;6:28-35.

46 Dreiser RL, Marty M, Ionescu E, et al. Relief of acute low back pain with diclofenac-k 12.5 mg tablets: flexible dose, ibuprofen 200 mg and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;41(9):375-385.

47 Ruoff G, Lema M. Strategies in pain management: new and potential indications for COX-2-specific inhibitors. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2003;25(Suppl):21-31.

48 Coats TL, Borenstein DG, Nangia NK, et al. Effects of valdecoxib in the treatment of chronic low back pain: results of a randomized, placebo controlled trial. Clin Ther. 2004;26(8):1249-1260.

49 Childers MK, Borenstein D, Brown RL, et al. Low-dose cyclobenzaprine versus combination therapy with ibuprofen for acute neck or back pain with muscle spasm: a randomized trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(9):1485-1494.

50 Cosale R. Acute low back pain: symptomatic treatment with muscle relaxant drugs. Clin J Pain. 1988;4:81-88.

51 Arbus L, Fajadet B, Aurbet D, et al. Activity of tetrazepam in low back pain: a double-blind trial versus placebo. Clin Trials J. 1990;27:258-267.

52 Borenstein DG, Korn S. Efficacy of a low-dose regimen of cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride in acute skeletal muscle spasm: results of two placebo-controlled trials. Clin Ther. 2003;25(4):1056-1073.

53 Schnitzer TJ, Ferraro A, Hunsche E, et al. A comprehensive review of clinical trials on the efficacy and safety of drugs for the treatment of low back pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(1):72-95.

54 Nadler SF, Stitik TP, Malanga GA. Optimizing outcome in the injured worker with low back pain. Crit Rev Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;11:139-169.

55 Hagen KB, Hilde G, Jamtvedt G, et al. Bed rest for acute low-back pain and sciatica (Cochrane Review). The Cohrane Library. (Issue 2):2004.

56 Hilde G, Hagen KB, Jamtvedt G, et al. Advice to stay active as a single treatment for low-back pain and sciatica (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. (Issue 2):2004.

57 Feldman JB. The prevention of occupational low back pain disability: evidence based reviews point in a new direction. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2004;13(1):1-14.

58 Coste J, Lefrancois G, Guillemin F, et al. Prognosis and quality of life in patients with acute low back pain: Insights from a comprehensive inception cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(2):168-176.

59 Goubert L, Crombez G, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Low back pain, disability and back pain myths in a community sample: Prevalence and interrelationships. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(4):385-394.

60 Curkovic B, Vitulic Babic-Naglic D, Durrigh T. The influence of heat and cold on pain threshold in rheumatoid arthritis. Z Rheumatol. 1993;52:289-291.

61 Bleakley C, McDonough S, MacAuley D. The use of ice in the treatment of acute soft-tissue injury. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(1):251-261.

62 Frost H, Lamb SE, Doll HA, et al. Randomised controlled trial of physiotherapy compared with advice for low back pain. Br Med J. 2004;329(7468):708.

63 van Tulder MW, Waddell G. Conservative treatment of acute and subacute low back pain. In: Nachemson A, Jonsson E, editors. Neck and back pain: the scientific evidence of causes, diagnosis, and treatment. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000:241-269.

64 Han JS. Acupuncture and endorphins. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361(1–3):258-261.

65 Deyo RA, Walsh NE, Martin DC, et al. A controlled trial of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and exercises for chronic low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1627-1634.

66 Marchand S, Charest J, Li J, et al. Is TENS purely a placebo effect? A controlled study on chronic low back pain. Pain. 1993;54:94-106.

67 Yueng C, Leung M, Chow D. The use of electro-acupuncture in conjunction with exercise for the treatment of chronic low back pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9(4):479-490.

68 Gam AN, Johansen F. Ultrasound therapy in musculoskeletal disorders: a meta-analysis. Pain. 1995;63:85-91.

69 Assendelft WJ, Morton SC, Yu EI, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain: A meta-analysis of effectiveness relative to other therapies. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(8):871-881.

70 MacDonald RS, Bill CMJ. An open controlled assessment of osteopathic manipulation in non-specific low back pain. Spine. 1990;15:364-370.

71 Sanders GE, Runert O, Tepe R, et al. Chiropractic adjustive manipulation on subjects with acute low back pain: visual analog pain scores and plasma beta-endorphines levels. J Manip Phys Ther. 1990;13:391-395.

72 Senstad O, Leböeuf Y de C, Borchgrevink C. Frequency and characteristics of side effects of spinal manipulative therapy. Spine. 1997;22:435-441.

73 Aina A, May S, Clare H. The centralization phenomenon of spinal symptoms: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2004;9(3):134-143.

74 Donelson R. The McKenzie approach to evaluating and treating low back pain. Orthop Re. 1990;19(8):681-686.

75 Kool J, De Bie R, Oesch P, et al. Exercise reduces sick leave in patients with non-acute non-specific low back pain: a meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2004;36(2):49-62.

76 van Tulder MW, Goossens M, Waddell G, et al. Conservative treatment of chronic low back pain. In: Nachemson A, Jonsson E, editors. Neck and back pain: the scientific evidence of causes, diagnosis, and treatment. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000:271-304.

77 Rainville J, Hartigan C, Martinez E, et al. Exercise as a treatment for chronic low back pain. Spine J. 2004;4(1):106-115.

78 Callghan JP, Gunning JL, McGill SM. The relationship between lumbar spine load and muscle activity during extensor exercises. Phys Ther. 1998;78(1):8-18.

79 McGill SM. Low back exercises: evidence for improving exercise regimens. Phys Ther. 1998;78(7):754-765.

80 Saal JA, Saal JS. Nonoperative treatment of herniated lumbar intervertebral disc with radiculopathy. An outcome study. Spine. 1989;14:431-437.

81 Rashiq S, Koller M, Haykowsky M, et al. The effect of opioid analgesia on exercise test performance in chronic low back pain. Pain. 2003;106(1–2):119-125.

82 Curatolo M, Bogduk N. Pharmacologic pain treatment of musculoskeletal disorders: current perspectives and future prospects. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(1):25-32.

83 Lierz P, Gustorff B, Markow G, et al. Comparison between bupivacaine 0.125% and ropivacaine 0.2% for epidural administration to outpatients with chronic low back pain. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2004;21(1):32-37.

84 Weiner DK, Ernst E. Complementary and alternative approaches to the treatment of persistent musculoskeletal pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(4):244-255.

85 Alaranta H, Rytohoski U, Ressannen A, et al. Intensive physical and psychological training program for patients with chronic low back pain: a controlled clinical trial. Spine. 1994;19:1339-1349.

86 Harhappa K, Mellin G, Jarvekaski A, et al. A controlled study on the outcome of inpatient and outpatient treatment of low back pain. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1990;22:181-188.

87 Hildebrandt J, Pfingsten M, Saur P, et al. Prediction of success from a multidisciplinary treatment program for chronic low back pain. Spine. 1997;22(9):990-1001.

88 Rainville J, Sobel JB, Hartigan C, et al. The effect of compensation involvement on the reporting of pain and disability by patients referred for rehabilitation of chronic low back pain. Spine. 1997;22(17):2016-2024.

89 Cohen I, Rainville J. Aggressive exercise as treatment for chronic low back pain. Sports Med. 2002;32(1):75-82.

90 van Tulder MW, Jellema P, van Poppel MNM, et al. Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low-back pain. (Cochrane Review) From the Cochrane Library. (Issue 2):2004.

91 Keller S, Ehrhardt-Schmelzer S, Herda C, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic back pain in an outpatient setting: A controlled randomized trial. Eur J Pain. 1997;1(4):279-292.

92 Casso G, Cachin C, van Melle G, et al. Return to work status 1 year after muscle reconditioning in chronic low back pain patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71(2):136-139.

93 Million R, Haavik-Nilsen K, Jayson M, et al. Evaluation of low back pain and assessment of lumbar corsets with and without back supports. Ann Rheum Dis. 1981;40:449-454.

94 Saal JA, Saal SS. Later stage management of lumbar spine problems. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 1991;2(1):221.

95 van Poppel MN, Koes BW, van der Ploeg T, et al. Lumbar supports and education for the prevention of low back pain in industry: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1789-1794.

96 McNair PJ, Heine PJ. Trunk proprioception: enhancement through lumbar bracing. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:96-99.

97 Buttermann GR. The effect of spinal steroid injections for degenerative disc disease. Spine J. 2004;4(5):495-505.

98 Slipman CW, Bhat AL, Gilchrist RV, et al. A critical review of the evidence for the use of zygapophyseal injections and radiofrequency denervation in the treatment of low back pain. Spine J. 2003;3(4):310-316.

99 Porta M, Maggioni G. Botulinum toxin (BoNT) and back pain. J Neurol. 2004;251(Suppl):5-8.

100 Difazio M, Jabbari B. A focused review of the use of botulinum toxins for low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(Suppl):155-162.

101 Yelland MJ, Del Mar C, Pirozzo S, et al. Prolotherapy injections for chronic low back pain: A systematic review. Spine. 2004;29(19):2126-2133.

102 Callaghan JP, McGill SM. Low back joint loading and kinematics during standing and unsupported sitting. Ergonomics. 2001;44(3):280-294.