CHAPTER 81 Medical Rehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

This chapter will provide the reader with a strategy for treating radicular pain and radiculopathy caused by lumbar disc herniations, stenosis, synovial cysts, and spondylolisthesis. These strategies rely on identifying the cause of nerve root irritation and tailoring the treatment algorithms based on the specific causes. The methods are based on the evidence-based literature and our groups’ collective experience. Because there is little or no evidence that commonly used treatments for radicular pain are either effective or not effective, our approach emphasizes the history and physical examination rather than imaging and electrodiagnostic studies. We will argue that the ultimate patient outcome is best predicted by the clinical presentation and early response to treatment.

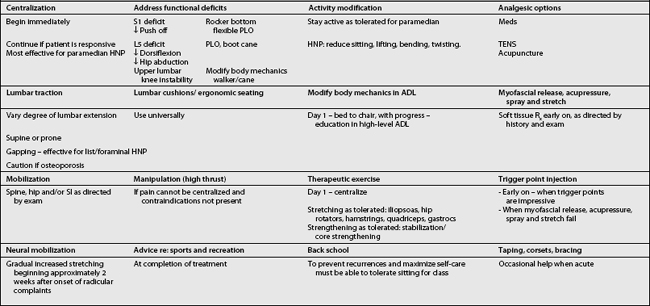

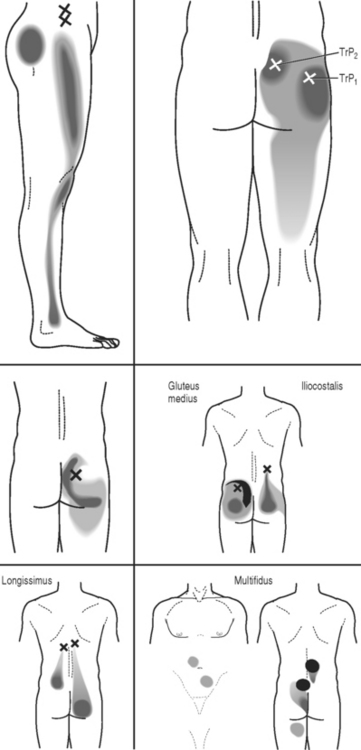

The art of treating a patient with lumbar radiculopathy involves considering many factors before deciding on or changing a course of action (Table 81.1).

THE MANAGEMENT OF LUMBAR RADICULOPATHY SECONDARY TO A PARAMEDIAN HERNIATED NUCLEUS PULPOSUS

Natural history

In a review article, Benoist reported that approximately 60% of patients with a symptomatic herniated disc will report a marked decrease in back and leg pain during the first 2 months, while 20–30% will still complain of back and/or leg pain at 1 year.1

Most studies indicate that most patients with a paramedian HNP can be satisfactorily treated with conservative measures.2–6

Komori et al. report: ‘Several well-designed studies of patients with HNP have revealed the satisfactory results of conservative treatment, although some authors have reported that about 20% of all patients had to be treated surgically during follow-up because of prolonged or aggravated leg pain.’7

Saal and Saal performed a retrospective cohort study on the success of nonoperative treatment of herniated lumbar discs with radicular pain and radiculopathy without associated spinal stenosis. All patients had a chief complaint of leg pain, positive straight leg raising of less than 60 degrees, herniated discs on computed tomography (CT) scan, and a positive electromyogram (EMG). The average follow-up time was 31.1 months. The patients underwent aggressive physical rehabilitation, including back school and stabilization training. Ninety percent reported a good or excellent outcome, and 92% returned to work after an average sick leave of 15.2 weeks.3–5,8

The patient’s history and examination not only are critical in making a diagnosis, but also allow us to forecast the likelihood of a patient’s responding to therapy alone as opposed to requiring epidural steroid injections or surgery.

Early indications for surgery

Review of the surgical literature reveals an interesting paradox. The results from surgical studies suggest that patients who do require surgery face a greater likelihood of successful outcome if they are operated on relatively soon after the onset of radicular pain. One study reported a worse overall prognosis for patients whose surgery takes place 12 months or more after the initial onset of radicular symptoms.9 Only with a clear understanding of both the natural history and effective conservative interventions for paramedian disc herniations can informed decisions be made regarding surgical consultation.

There are several studies that help predict which patients will respond best to nonoperative care. Patients who present with negative crossed straight leg raising, and the ability to extend the lumbar spine without associated radicular pain, usually respond well to conservative management.10 Patients with normal or very mild neurological deficits also have a better chance of responding to nonoperative care. We also feel that outcome is better when the onset of discogenic radicular symptoms was acute rather than insidious.

There are numerous reports of significant shrinkage, or even disappearance, of extruded herniations that usually occurs over a 3–6-month period.1,11–14 Subligamentous disc herniations, however, are often more stubborn and resolve more slowly than extruded herniations.

Activity modification

In a review of ten trials of bed rest and eight trials of advice to stay active, Waddell et al. reported consistent findings showing that bed rest is not an effective treatment for acute low back pain, and in fact may delay recovery.15 Although these patients were not carefully separated into those with axial back pain as opposed to those with radicular pain, the authors concluded that patients should be advised to remain active.

In a trial comparing 2 days of bed rest with 7 days of bed rest for patients with mechanical low back pain without neurological deficits, Deyo et al. reached a similar conclusion: the group with the shorter period of bed rest missed fewer days of work.16 No other difference was noted between the two groups in terms of their functional, physiological, or perceived outcomes.

In fact, there is no evidence that bed rest hastens recovery or improves outcome in patients with radicular pain and radiculopathy. On the contrary, numerous studies demonstrate the deterioration of many physiological systems as a result of bed rest. Abnormalities that develop include, but are not limited to, decreased cardiac output, atelectasis, orthostatic hypotension, decreased aerobic capacity, diffuse muscular atrophy, constipation, renal lithiasis, osteopenia, and depression.

On the other hand, Wiesel et al. conducted a study on military recruits with nonradiating back pain and found that those who were on brief periods of bed rest had a faster return to full duty than those who remained ambulatory.17

Despite numerous studies indicating that continued activity is preferable to bed rest, many patients have too much pain to get out of bed and will require a short period of bed rest until the severe pain lessens. Pain can often be reduced by the following: lying supine with hips and knees both in significant flexion, supported by pillows underneath the calves; lying on either side in a fetal position with the pillow between the knees; and short periods of lying prone with a pillow under the mid-abdomen. In addition, patients are advised to use firmer mattresses, with a soft, thin surface layer.18

Clinical use of medications

There is no evidence that any oral medication will change the course of lumbar radiculopathy due to a herniated disc. On the other hand, medication can help control symptoms. Patients are, however, warned to avoid activities that they know would be painful or inadvisable when not taking their medications because such activity could ultimately exacerbate rather than alleviate their symptoms (Table 81.2).

| Non-narcotic analgesics | NSAIDs | Anticonvulsants |

|---|---|---|

| Analgesic effect only | Analgesic effect primarily | For pain with neuropathic quality, ???, burning |

| Acetaminophen – max 4 g per day | Disease altering for: synovial cyst, Facet syndrome | Most common: gabapentin, titrate up to 1800 mg per day for most, max. 3600 mg per day |

| Tamadol – max 100 g every 6 h | Selective COX-2 inhibitors, meloxicam | |

| Caution: interaction with serotonergic drugs | Salsalate – ↓GI toxicity, normal bleeding time | Caution: somnolence, dizziness, nausea |

| Caution: fluid retention, GI toxicity – add PPI, misoprostol, ↑ bleeding time, ↑ vascular events | ||

| Narcotic analgesics | Oral corticosteroids | Antidepressants |

| Analgesic effect only | Theoretically decrease root inflammation | For pain with neuropathic quality |

| Short acting | Not proven to alter course | Tricyclics – most common is amitriptyline, variable sedation, variable anticholinergic |

| Long acting – for hours, for chronic pain | Caution: AVN, multiple side effects | |

| Caution: sedation – add provigil, constipation – add laxatives, nausea, pruritus, addictive potential | SSRIs – not well studied | |

| Effexor, Paxil, duloxetine – theoretical benefit of increasing both central serotonin and neuroepinephrine | ||

| Muscle relaxants | Anti-TNF | Topical agents |

| Variably sedating | Experimental | For pain with neuropathic quality |

| Role when diffuse muscular tenderness | Anti-inflammatory – disease modifying | Lidocaine patch, capsaicin |

| Some with anticholinergic effect | ||

| Some with addictive potential |

Nonnarcotic analgesics

Tramadol (Ultram) is a weak opioid agonist with analgesic properties equal to acetaminophen/codeine combination preparations that is well tolerated by most, including the elderly. Tramadol is often prescribed as 50 mg to a maximum of 100 mg every 6 hours. It is also available in a combination tablet, which includes 37.5 mg of tramadol and 325 mg of acetaminophen (Ultracet). Tramadol has the advantage of causing less sleepiness and constipation than narcotics, with a similar analgesic benefit to mild narcotics. Uncommon side effects include sleepiness, dizziness, and nausea. Tramadol may decrease the seizure threshold in patients with epilepsy.19

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs

No studies show that nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) improve either the objective signs or the long-term outcome in patients with lumbar radiculopathy. There is, however, some evidence that NSAIDs are effective for short-term symptomatic relief in patients with acute low back pain, but no specific type appears to be more effective than the others.20

There is evidence that antiinflammatories can reduce inflammatory mediators in animal studies.21 A comparison of indomethacin with placebo did not demonstrate a difference in objective neurological signs or subjective reports of pain relief.22 One study revealed a symptomatic improvement with meloxicam in acute sciatica when compared with placebo and diclofenac in a double-blinded trial.23

The first concern about the cardiovascular safety of rofecoxib emerged with the VIGOR study, reported in 2000. It involved a fivefold increase in myocardial infarction and a twofold increase in stroke, or cardiovascular death among 8076 rheumatoid arthritis patients treated for a median of 9 months with rofecoxib compared with naproxen.24–27 Further questions about the cardiovascular safety of rofecoxib were raised in 2001 by an overview of the clinical trial data.28 These data prompted the FDA to initiate a label change in 2002, highlighting the potential cardiovascular risks of rofecoxib. Despite more recent observational studies also suggesting an increased early (within the first 30 days of treatment) and late (beyond 30 days) risk of acute myocardial infarction or sudden cardiac death with rofecoxib,29,30 conclusive evidence of increased cardiovascular risk from adequately powered randomized trials was lacking.31

The decision by Merck to withdraw rofecoxib worldwide was prompted by an unexpected source. APPROVe (Adenomatous Polyp Prevention On Vioxx) was a multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of 2600 patients designed to examine the effects of treatment with rofecoxib on the recurrence of neoplastic polyps of the large bowel in patients with a history of colorectal adenoma.27 An interim analysis of this trial demonstrated an almost twofold increase in cardiovascular events in patients treated with rofecoxib (25 mg daily) compared with placebo. When these data are extrapolated to the Australian population, the increased risk of 16 events per 1000 patients treated for up to 3 years equates to a potential excess of several thousand cardiovascular events caused by rofecoxib. This may represent an underestimate of the number of events caused by rofecoxib, because patients with inflammatory arthritis are likely to be at higher baseline risk of cardiovascular events than the ‘low-risk’ population included in APPROVe.27

Muscle relaxants

Some studies support a weak benefit of muscle relaxants over placebo for the treatment of axial back and neck pain,32–35 but we are not aware of any trials on the use of muscle relaxants for lumbar radiculopathy.

Antidepressants

The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of radicular pain is largely unsupported. In studies comparing tricyclic antidepressants with SSRIs for chronic pain syndromes, tricyclics were found to be more effective in every case.36

Duloxetine (Cymbalta), a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SSNRI), is available in doses of between 20 mg and 120 mg per day, administered either once or twice daily. Efficacy has been demonstrated in diabetic peripheral neuropathy in two randomized, double-blind, 12-week, placebo-controlled studies in which patients were followed for at least 6 months.37,38 Improvements were seen as early as 1 week after initiating the drug. Doses above 60 mg per day did not offer greater improvement. The drug is contraindicated in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma, as well as in patients with end-stage renal disease or hepatic insufficiency. Most commonly observed adverse effects include nausea, dry mouth, constipation, fatigue, decreased appetite, somnolence, and increased sweating. The overall discontinuation rate due to adverse events was 14%, compared with 7% for placebo.

Anticonvulsants

The antiepileptic drug lamotrigine (Lamictal) has recently been studied in the management of intractable sciatica.39 The study demonstrated improvements in lumbar range of motion, straight leg raising, and a short form of the McGill pain questionnaire.

Oral corticosteroids

Although short courses of corticosteroids are often prescribed for radicular pain, there are no double-blind, placebo-controlled trials supporting or not supporting the use of corticosteroids for the treatment of radicular pain caused by a herniated disc or spinal stenosis.40 Because of the risk of avascular necrosis of joints with the intake of 60 mg doses of dexamethasone,41 we only occasionally treat radicular pain with oral corticosteroids.

Antitumor necrosis factor medications

Several recent studies show that tumor necrosis factor TNF-α may be a significant pain mediator in radicular pain.42,43 According to Murata et al.,43 TNF-α is produced and released from chondrocyte-like cells of the nucleus pulposus and acts to reduce nerve conduction velocity, induce intraneural edema and intravascular coagulation, reduce blood flow, and cause myelin splitting. Murata treated rats with intraperitoneal infliximab (Remicade), a selective inhibitor of TNF-α and showed that injected rats produced a significant reduction in histologic changes in the dorsal root ganglion.

Korhonen et al. demonstrated the beneficial effect of a single infusion of infliximab, 3 mg per kg, for herniation-induced sciatica.44 Eight of the 10 patients treated with infliximab remained pain-free 1 year after injection, and no ill effects were reported in any of the 10 patients. Six of the 10 had achieved pain-free status at 2 weeks, seven at 4 weeks, and nine at 3 months. All had severe sciatic pain below the knee, positive straight leg raising at less than or equal to 60 degrees, and a disc herniation concordant with symptoms on MRI. By comparison, only 43% of the 62 control patients, who also had disc herniation-induced sciatica, were pain free at 12 months.

Topical agents

Lidocaine 5% patch reduces pain associated with postherpetic neuralgia without toxicity. The only side effect is an occasional local rash. Lidoderm patches have been tried in various conditions associated with neuropathic pain. Although the drug’s insert instructs that the use should be an on-and-off 12-hour schedule, there does not appear to be any physiological risk to 24-hour use of the patch. There are, however, no studies demonstrating efficacy in lumbar radiculopathy.45

Physical therapy

Superficial cold (cryotherapy)

Application of cold packs placed in wet towels or ice massage can afford temporary analgesia.46 Cold causes vasoconstriction of superficial vessels, indirectly resulting in vasodilatation of deeper vessels. Contraindications to cryotherapy include cold hypersensitivity and urticaria, Raynaud’s phenomenon, cryoglobulinemia, and paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria. In addition, cryotherapy should not be applied to areas of skin anesthesia or decreased circulation. Vapo-coolant spray and stretching (spray and stretch) can also be used for the management of myofascial pain. This is often used in combination with trigger point injections as described by Travell and Simons.47

Heat (thermotherapy)

Heat can be used as a temporary analgesic,48 and can be administered by hydrocollator packs, heating pads, hydrotherapy, or thin wraps that can be placed on the skin for a prolonged application. In fact, heat wraps have been demonstrated to be more effective than ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute low back pain,49 and are helpful for relieving overnight pain.50 Diathermy and ultrasound are usually ineffective in reducing radicular pain.

Electrotherapy

Various forms of electrical stimulation, such as high-voltage pulsed galvanic stimulation or interferential electric stimulation, can be applied in the office setting, either in isolation or in conjunction with heat or cold. These modalities seem to contribute to relaxation and temporary analgesia, perhaps through decreasing spasm. Electrical stimulation should not be applied to patients with cardiac pacemakers or defibrillators, or to anesthetic areas or incompletely healed wounds.51

TENS uses a small pulse generator clipped to the skin connected to one to four variously placed transcutaneous electrodes. The pulse frequency, amplitude, and wave form are adjusted to achieve maximal effect. TENS can provide analgesia,52 but there are no specific trials evaluating the efficacy for treating lumbar radiculopathy. In general, TENS has an occasional role and may be most useful in decreasing night pain.

Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS) uses needle probes similar to those used in acupuncture to deliver electrical pulses to peripheral sensory nerves at dermatomal levels.53 In a trial comparing PENS, sham PENS, TENS, and exercise, both PENS and TENS were effective in reducing sciatic pain. Although PENS was more effective, because it is a tedious in-office procedure, supported by only a few studies, and does not help structurally, PENS has not been used in our management of radicular pain

Lumbar traction

The following are the current spinal traction techniques:

The evidence supporting traction remains inconclusive, but may in part be due to poor study design. A review article found no conclusive evidence that any form of traction is efficacious in the treatment of low back pain, with or without radicular involvement.54 However, several studies have revealed a reduced size of herniation following traction.55,56 Nachemson and Elstrom demonstrated a 20–30% reduction in intradiscal pressure with traction.57 Fifteen minutes of sustained traction will cause increased height.58

Despite the lack of clinical evidence, many of our otherwise unresponsive patients have a lessening of symptoms following lumbar traction. When treating patients with lumbar radicular pain and radiculopathy, we use traction if symptoms are not promptly responsive to centralization techniques. Our protocol uses approximately 15 minutes of intermittent traction alternating a 40–50-second pull with 10–15-second rest period. If necessary in larger patients, we will use up to 150 pounds of traction and in smaller or elderly patients as little as 60 pounds of traction. When treating patients with paramedian disc herniations, we have often initiated traction with the lumbar spine in flexion, and have attempted to gradually modify the traction so that the lumbar spine is more in extension, in accordance with the principle of the centralization phenomenon as introduced by Robin McKenzie (see Centralization below). In fact, traction is administered in a prone position in patients that centralize in extension (Fig. 81.1). When radicular pain is persistent, we have used a gapping technique so that the pull is angulated somewhat toward the asymptomatic side (Fig. 81.2).

Back schools and patient education

Patient education may be the most important factor in the prevention of recurrent episodes of discogenic pain, and back schools are an excellent forum for providing this education. In existence since 1977, back schools in Sweden, Canada, and California boast validated success in reducing the incidence of back pain.59–61

Back school theory is primarily based on the effects of body posture on disc pressure published by Dr. Alf Nachemson62 and the Robin McKenzie approach.63

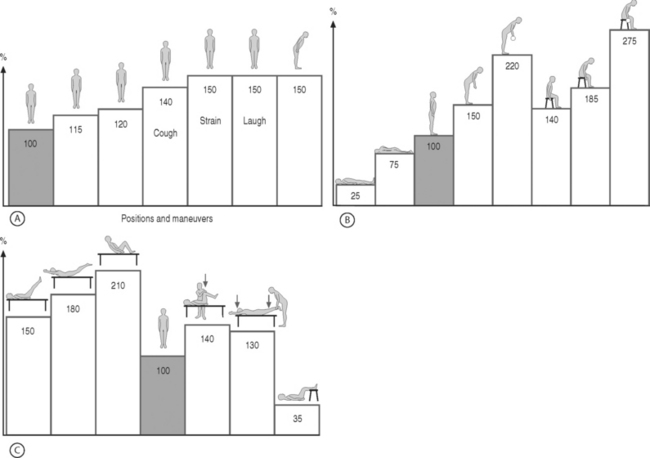

Dr. Nachemson measured the intradiscal pressure in volunteers in numerous positions, while performing activities of daily living, and performing various exercises (Fig. 81.3). From these studies, he found lower intradiscal pressures when standing compared to sitting. Bending forward in either the sitting or standing position increased intradiscal pressure above sitting pressures. Coughing and straining caused significant rises in intradiscal pressure. Lifting weights further from the body raises pressure more than lifting weights closer to the body. These increases in pressure are often reflected in patients increased pain during positions and activities that increase intradiscal pressure.

Centralization

Many physicians and physical therapists use the McKenzie method in both assessment and treatment of lumbar spine patients, including those with radiculopathy. In 1972, McKenzie first presented favorable outcomes of 500 consecutive patients treated according to his centralization protocol.64 McKenzie and his disciples categorize patients with back pain, leg pain, or both based on whether their pain ‘centralizes’ in response to spinal movement.

Assessment and management of patients with an intact contiguous nucleus pulposus using the McKenzie Method® assumes that movement will effect the position of the nucleus pulposus within the anulus fibrosus. Although an assumption, many studies support his belief,65–68 and in addition one study shows a good inter-tester reliability.69

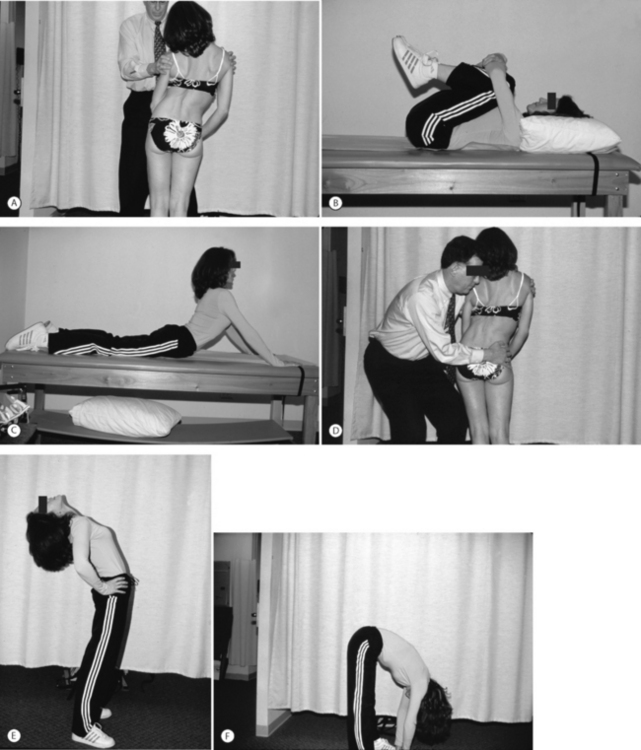

The McKenzie approach examines the patient during repeated end-range movements when standing, forward bending, back bending, and side bending. Similar repeated end-range movements are performed while the patient is recumbent, including knees to chest while supine, passive extension while prone, and prone lateral shifting of hips off the midline. As the patient performs each of these maneuvers, the clinician records whether there is a directional preference or centralization, as opposed to peripheralization, of pain (Fig. 81.4). Based on the results, the patient is categorized and a treatment plan is suggested.

Most patients with mechanical pain have extension as their directional preference which may be a positive prognostic sign. Kopp et al.10 studied 67 patients that required hospital admission for lumbar pain with radiation to the calf or foot. These patients had positive root tension signs, and were determined to have lumbar disc disease with all other etiologies of lumbar radiculopathy ruled out. The McKenzie approach was used on these 67 patients. Of the 35 patients who were able to be treated without surgery, 97% were able to achieve normal lumbar extension within 3 days of admission to the hospital. Only 6% of the 32 surgically treated patients were able to achieve normal lumbar extension preoperatively.

In 1990, Donelson et al. reviewed 87 patients with back and radiating leg pain.70 Centralization occurred in 76 (87%) and in the majority centralization occurred within 2 days of the initial visit. All of the 59 patients who had an excellent outcome experienced centralization of pain during the initial evaluation. In the 13 patients with good results, 10 had centralization, 4 of 7 patients with fair results centralized; and only 3 or 8 patients with poor results centralized.

A review of the literature by Wetzel and Donelson concluded that McKenzie centralization protocol benefited patients with lumbar radiculopathy who were able to centralize. The authors advised that surgery should not be considered until these patients had an adequate trial of the centralization technique.71

Snook et al. also demonstrated benefit in low back pain when patients restricted flexion activities during early morning hours when discs are fully hydrated and thus more susceptible to intra-anular prolapse.72

Donelson and Aprill et al. demonstrated a correlation between the McKenzie assessment and results of discography and showed that a significant number of patients who centralize have an intact outer anulus.73 Sixty-three patients with back and lower extremity pain based on disc disease were studied. The majority of these patients had pain below the knee. None had neurological deficits and all had at least one MRI study and none required surgery. Fifty of the patients were able to centralize their referred pain, and in this group 74% had positive discograms and 91% of those had an intact anulus. In the 25% of patients who peripheralized their pain during McKenzie assessment, 69% had positive discograms, but only 54% of those had an intact anulus. Twenty-five percent of patients did not centralize or peripheralize their pain in response to testing maneuvers and only 12.5% of these patients had positive discograms.

Many studies74–79 have shown that centralization is a better predictor of outcome than the location of the initial pain. For this reason, our practice uses centralization to predict outcome and guide treatment. The ability of a patient with lumbar radicular pain and radiculopathy to centralize is assessed as soon as possible. We find that a high percentage of these patients are able to centralize and will respond to the appropriate exercises and biomechanical advice. Most centralize with extension, and respond to passive extension exercise programs. We have, however, found that patients who routinely perform multiple repetitions of prone lying press-ups often develop or exacerbate prior musculoskeletal conditions. These include facet pain caused by increased stress on posterior lumbar elements, increased cervical pain caused by strain on the cervical spine, acromioclavicular joint inflammation, and medial epicondylitis. We do, however, modify the passive extension exercises to avoid these problems. For instance, one can insert pillows underneath the head and chest to create passive extension, instead of relying wholly on the upper extremities. The patient can also move the hands caudally to allow a traction force to the lumbosacral spine with less stress on the posterior element.

Therapeutic exercises

Strengthening

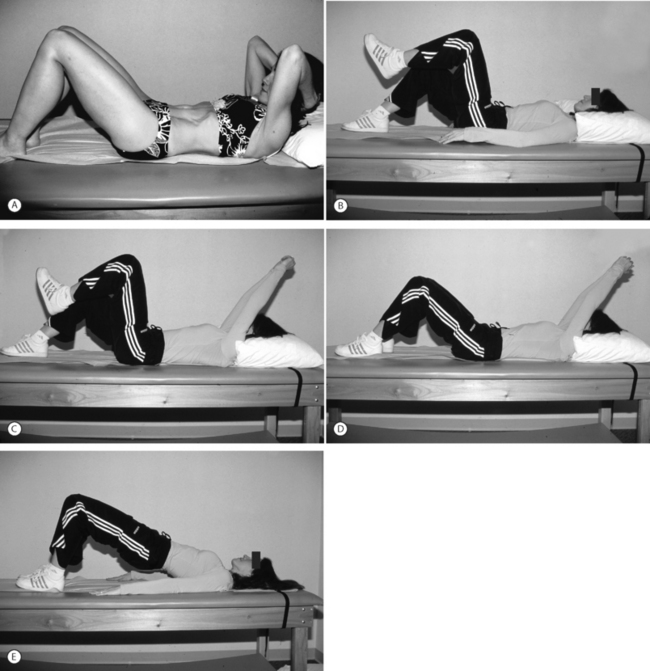

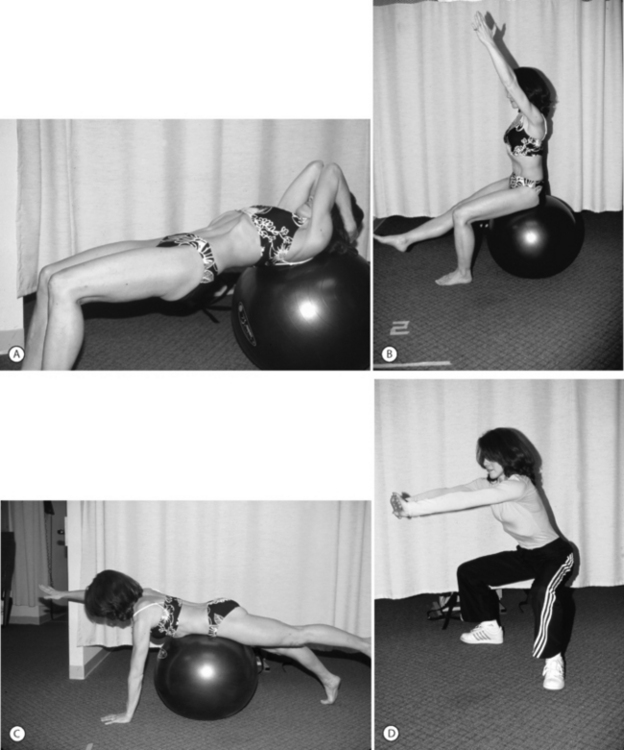

Treating back disorders with strengthening has been prescribed for at least three-quarters of a century. Strengthening of the flexion musculature is an important part of the Williams flexion exercises.80 Patients have been given flexion, extension, or mixed exercise programs in an effort to strengthen trunk musculature and unload the lumbar spine. In 1989, the Saal brothers formalized their stabilization/strengthening program.3,81 This program, which consists of gradually more challenging trunk strengthening exercises, quickly became incorporated into rehabilitation programs throughout the United States (Figs 81.5, 81.6).

Within the past several years, ‘core strengthening’ has rapidly become a catchphrase in rehabilitation programs, gyms, and fitness centers throughout the country. A core strengthening program incorporates more functional movements of the body as a whole, while maintaining contracted trunk musculature. Improved clinical outcomes following core strengthening have not been proven. In a review of core strengthening, Akuthota and Nadler wrote, ‘To our knowledge, no randomized controlled trial exists on the efficacy of core strengthening. Most studies are prospective, uncontrolled case studies.’82 A 2002 study by Nadler et al. evaluated the incidence of low back pain before and after incorporation of a core strengthening program for athletes. This study was unable to demonstrate a significant change in overall incidence of low back pain.83

Nonetheless, numerous models demonstrate why stronger trunk musculature should afford greater stability to the lumbar spine.84 Studies have demonstrated that many muscles contract during stabilization exercises.85 Other studies have demonstrated that increased abdominal pressure stabilizes the lumbar spine. Such increased pressure can occur either as a result of antagonistic muscle co-activation or abdominal muscle contraction.86,87 It has also been shown that simply stimulating paraspinal musculature stabilizes the lumbar spine.88

Furthermore, investigators have demonstrated various trunk muscle abnormalities in the population of patients who have back problems. The latency for lumbar muscle contraction is longer in patients with sciatica.89 Patients who were 5 years post-laminectomy demonstrated persistent atrophy of the multfidi, but to a much lesser extent than in patients that had good outcomes from surgery.90 Multifidus muscles were noted by Hides to be weak 10 weeks after a low back pain episode.91 Arendt-Nielsen noted active paralumbar muscles on EMG during gait in chronic low back pain patients, but silent lumbar paraspinal musculature during gait in controls.92 Hodges found a late onset of transversus abdominus contraction in patients with low back pain while performing upper extremity activities.93 In 1997, Cholewicki et al. studied trunk flexor–extensor musculature in healthy individuals, and performed a number of calculations with the use of a model.94 They concluded that average antagonistic flexor–extensor muscle co-activation levels were 1.7% of maximum voluntary contraction when there was no load added, and 2.9% when a 32 kg mass was added to the torso. They further calculated that an individual with spine injury and stiffness would exert 3.4% of maximum voluntary contraction of antagonist muscle co-activation for no extra load, and 5.5% when 32 kg were added. The authors stated that, ‘It seems reasonable to expect that the requirements of spine stability in a neutral posture should not demand more than 5% maximum voluntary contraction of muscle co-activation, because that could lead to muscle fatigue during the entire day.’

Although we prescribe trunk strengthening exercises in our practice, these exercises are not emphasized more that other treatment options. In addition, many of these exercises increase intradiscal pressure. Exercises that might exacerbate symptoms of patients with disc herniations include hyperextension exercises, isotonic truck flexion exercises such as sit-ups, and exercises involving trunk torsion. In this respect, the literature does not support a correlation between strength of core muscles and the reduced incidence of lumbar disc disease. No studies specifically demonstrate that individuals with weaker trunk musculature are at higher risk for disc problems. In fact, the greatest incidence of first-time disc herniations is between the age of 25 and 29, when one can only assume that the trunk musculature is stronger than in older individuals.

Mobilization

It is important that a patient have good mobility of the adjacent spinal segments which should theoretically reduce the stress at the level of the herniated disc. Good hip mobility is also important, because increased torsional lumbar spine forces occur in patients who have contractured hips. Normal sacroiliac alignment and mobility should also reduce forces on the lumbar spine.

Myofascial release

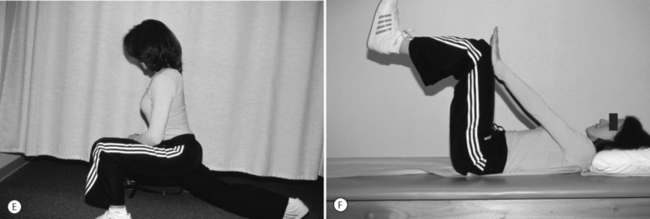

Many patients with lumbar radiculopathy develop localized areas of tenderness within the lumbar and gluteal musculature, and occasionally in the lower extremity muscles. These tender areas are usually trigger points. It is unclear why or how these areas of muscle tenderness occur, but many physicians, including ourselves, feel that trigger points contribute to pain.95

Travell and Simons have detailed maps of trigger point pain referral zones for trigger points for almost every muscle (Fig. 81.7).96 Although there are no double-blind, controlled studies validating any type of trigger point treatment, we believe that treating trigger points may reduce pain, particularly when palpation of a trigger point generates radiating pain.

Neural mobilization

In the 1980s, physical therapists began using sophisticated tension tests to assess adhesions and nervous system injury.97 These new diagnostic procedures led to passive mobilizing treatment techniques called neural mobilization. In part, neural mobilization is the result of studies showing increased tension in lumbar nerve roots as a result of passive neck flexion.98,99 Similarly, altered neck and arm pain may be demonstrated by the addition of ankle dorsiflexion to a straight leg raising maneuver.

Neural mobilization advocates view the nervous system as a continuous organ that stretches from the brain to the feet. In 1987, Butler introduced the term ‘adverse mechanical tension in the nervous system,’ and discussed how to diagnose and treat neurogenic pain and neurological symptoms.99 Tension tests not only produce an increase in tension within the nerve, but also between the nerve and surrounding tissues. In 1976, Sunderland demonstrated that inflammatory changes around the nerve could lead to changes in the connective tissues within the nerves, with a resultant intraneural fibrosis.100 As a result of this fibrosis, nerves lose elasticity, and tension tests are altered.

Manipulation

Manipulation involves the application of passive, controlled forces and moment loads to alter the mechanical behavior of the functional spinal unit and internal stress distributions.101 Although manipulation procedures encompass an extremely broad array of treatments that cause passive movement to a portion of the body, we will restrict our discussion of manipulation in this chapter to rapid, high-thrust maneuvers.

Several studies of manipulation demonstrate short-term efficacy.102–104 Practitioners who believe in the McKenzie approach to radicular pain and radiculopathy also probably believe that patients can improve more rapidly by adding spinal manipulation.

High-thrust manipulation is rarely indicated in the treatment of radicular pain caused by a lumbar disc herniation. If the patient centralizes his or her pain with McKenzie treatments, then manipulation is not needed, and when the patients do not centralize, high-thrust manipulation has a low success rate and an increased complication rate. Contraindications to manipulation include cauda equina syndrome, undiagnosed loss of bowel or bladder control, undiagnosed progressive neurological deficit, severe osteoporosis, primary or metastatic tumors, or conditions containing unstable motion. Cauda equina syndrome is, however, a rare complication and only 26 cases are reported in the world literature. Local, transient discomfort is not uncommon and is probably underreported. High-thrust manipulation in patients with disc herniations may result in increased radicular pain and rarely minor radicular neurological deficits.

Acupuncture

Our review of the acupuncture literature revealed no controlled studies supporting its use in the treatment of lumbar disc herniations. Most studies have major methodological flaws, and rarely was the treated population well described.106 Acupuncture may, however, provide temporary analgesia, and practitioners may decide to pursue this treatment based on expense and ease of access. We use acupuncture on occasion for analgesia for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy.

Taping, corsets and braces, and ergonomic aids

Lumbar orthotics and braces will variably restrict range of motion by operating through a three-point pressure system. They may increase postural awareness and might possibly reduce disc pressure by supporting weak abdominal muscles and increasing intra-abdominal pressure. Nachemson and Morris determined that an inflatable corset was able to decrease intradiscal pressure by 25–30%.107

Several types of lumbar orthoses are available.108 Flexible lumbosacral corsets are constructed from fabric, such as Neoprene, canvas, or elastic, and encircle the lumbosacral area. These devices provide postural feedback while mildly restricting range of motion, and may slightly increase intra-abdominal pressure. Corset closure is achieved with laces, buckles, or Velcro.

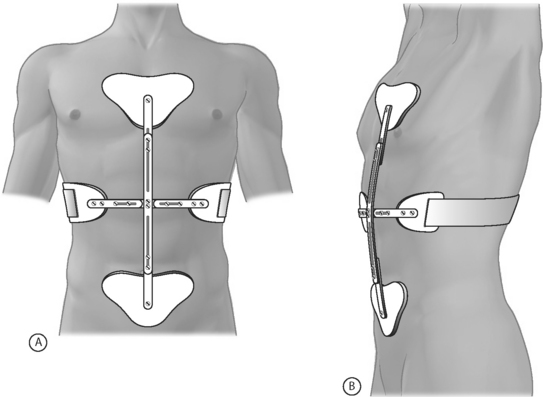

The first is the Cash orthosis (Fig. 81.8) that consists of anterior horizontal and vertical bars forming a large cross. The vertical bar extends from the sternum to the pubic bone. The brace fastens with straps in the back, and is lightweight and easy to put on and take off. It accommodates large breasts, but is difficult to fit on patients with protuberant abdomens. It certainly discourages thoracolumbar flexion, since any flexion is met by rigid pressure over the patient’s sternum or pubic bone. There are, however, no controlled studies to validate the effectiveness of this brace.

Fig. 81.8 Cash orthosis.

(Adapted from Cole A, Herring S. The low back pain handbook: a guide for the practicing clinician, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2003:453–457.)

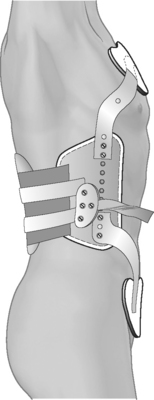

The second is the Jewitt hyperextension brace (Fig. 81.9) that consists of an anterior frame that is attached to sternal, suprapubic, and thoracolumbar pads and will also maintain the patient in a hyperextended posture.

Fig. 81.9 Jewitt hypertension brace.

(Adapted from Cole A, Herring S. The low back pain handbook: a guide for the practicing clinician, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2003:453–457.)

We utilize corsets and braces in approximately 5–10% of patients with paramedian disc herniations. Braces are particularly appropriate for patients who must sit for hours in poorly supportive seating, patients who are making slow progress and demonstrate poor postural support, patients who are returning to work or athletics, and patients whose symptoms are particularly sensitive to lumbar flexion and extension and who are not progressing in the rehabilitation program.

Trigger point injections

Although there are no randomized, controlled studies supporting the use of trigger point injections, the technique is used by many and there is copious literature describing trigger point injection techniques. Trigger points are localized intramuscular areas of tenderness that usually feel nodular when palpated. These trigger points are thought to have a characteristic referral pattern when palpated. Authors have described taut bands within trigger points that, after palpation, will cause referral of pain into a location that is typical for that muscle.96

We use 25-gauge needles and inject approximately 2 cc of 0.5% lidocaine into each trigger point. We will add small doses of corticosteroid, such as 1 mg of Decadron, only if the patient had persistent soreness after previous trigger point injections. When the patient’s pain is reproduced during needle entry, we usually ‘dry needle’ the trigger point several times.

VARIATIONS IN TREATMENT FOR OTHER MECHANICAL CAUSES OF LUMBAR RADICULOPATHY

See Table 81.3 for a summary.

Lateral or foraminal herniated nucleus pulposus

Although over 90% of these patients can be successfully treated without surgery, a significant percentage, between 40% and 70%, will require epidural injections. Although patients are advised to avoid prolonged sitting, it is impractical to tell this patient population not to sit since that is often their only comfortable position. These patients often require more frequent and stronger analgesics and neural modulating agents than patients with a paramedian disc herniation. Due to the more frequent occurrence of intense nocturnal pain, a trial of TENS and topical agents is more often attempted.

SUMMARY

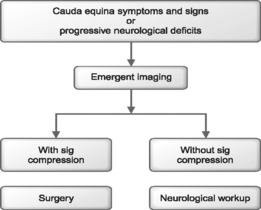

Patients with a cauda equina syndrome or progressive neurological deficits should be emergently studied and referred to a spine surgeon if the results of studies indicate a compressive lesion.

Back schools are effective in reducing the incidence of recurrence of low back pain.

High-thrust manipulation is rarely indicated in the management of lumbar radiculopathy.

Acupuncture provides temporary analgesia for some patients with lumbar radiculopathy.

1 Benoist M. The natural history of lumbar disc herniation and radiculopathy. Joint Bone Spine. 2002;69:155-160.

2 Bush K, Cowan N, Katz DE, et al. The natural history of sciatica associated with disc pathology. A prospective study with clinical and independent radiologic follow-up. Spine. 1992;17:1205-1212.

3 Hakelius A. Prognosis in sciatica: a clinical follow-up of surgical and non-surgical treatment. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1970;129:1-76.

4 Hasue M, Fujiwara M. Epidemiologic and clinical studies of long-term prognosis of low back pain and sciatica. Spine. 1979;4:150-155.

5 Saal JA, Saal JS. Nonoperative treatment of herniated lumbar intervertebral disc with radiculopathy. An outcome study. Spine. 1989;14:431-437.

6 Weber H. Lumbar disc herniation: a controlled, prospective study with 10 years of observation. Spine. 1983;8:131-140.

7 Komori H, et al. Factors predicting the prognosis of lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation. J Orthop Sci. 2002;7:56-61.

8 Weber H, et al. The natural course of acute sciatica with nerve root symptoms in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the effect of piroxicam. Spine. 1993;18:1433-1438.

9 Ng LCL, Sell P. Predictive value of the duration of sciatica for lumbar discectomy. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2004;86:546-549.

10 Kopp JR, et al. The use of lumbar extension in the evaluation and treatment of patients with acute herniated nucleus pulposus. Clin Orth Rel Res. 1986;202:211.

11 Saal JA, Saal JS, Herzog RJ. The natural history of lumbar intervertebral disc extrusions treated nonoperatively. Spine. 1999;20:1821-1927.

12 Bozzao A, et al. Lumbar disc herniation: MR imaging assessment of natural history in patients treated without surgery. Radiology. 1992;185:135-141.

13 Delauche-Cavallier MC, et al. Lumbar disc herniation. Computed tomography scan changes after conservative treatment of nerve root compression. Spine. 1992;17:927-933.

14 Takada E, et al. Natural history of lumbar disc hernia with radicular leg pain: spontaneous MRI changes of the herniated mass and correlation with clinical outcome. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2001;9(1):1-7.

15 Waddell G, et al. Systematic reviews of bed rest and advice to stay active for acute low back pain. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47(423):647-652.

16 Deyo RA, et al. How many days of bed rest for acute low back pain? A randomized clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(17):1064-1070.

17 Wiesel SW, Cuckler JM, DeLuca F, et al. Acute low back pain: an objective analysis of conservative therapy. Spine. 1980;5:324-330.

18 Garfin SR, Pye SA. Bed design and its effect on chronic low back pain – a limited controlled trial. Pain. 1981;10:87-91.

19 Mullican WS, Lacy JR. Tramap-ANAG-600 study group: tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets and codeine/acetaminophen combination capsules for the management of chronic pain: a comparative trial. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1429-1445.

20 van Tulder MW. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. A systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine. 2000;25(19):2501-2513.

21 Cornefjord M, et al. Nucleus pulposus-induced nerve root injury: effects of diclofenac and ketoprofen. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:57-61.

22 Goldie I. A clinical trial with indomethacin (indomee) in low back pain in sciatica. Acta Orthop Scand. 1968;39:117-128.

23 Dreiser RL, et al. Oral naloxicam is effective in acute sciatica: two randomized double-blind trials vs. placebo or diclofenac. Inflamm Res. 2001;50(Suppl 1):S17-S23.

24 Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520-1528.

25 Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritic and rheumatoid arthritis. The CLASS study: a randomised controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284:1247-1255.

26 Department of Health and Ageing. Expenditure and prescriptions twelve months to 30. Available at: www.health.gov.au/internet/wcms/publishing.nsf/Co, June 2004. (accessed Oct 2004)

27 Department of Health and Ageing. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Consumer level recall of arthritis drug. Media release. Available at: www.tga.gov.au/media/2004/040930_vioxx.htm. (accessed Oct 2004)

28 Lisse JR, Perlman M, Johansson G, et al. Gastrointestinal tolerability and effectiveness of rofecoxib versus naproxen in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a randomised, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:539-546.

29 Mukherjee D, Nissen SE, Topol EJ. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with selective COX-2 inhibitors. JAMA. 2001;286:954-959.

30 Solomon DH, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, et al. Relationship between selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and acute myocardial infarction in older adults. Circulation. 2004;109:2068-2073.

31 Topol EJ, Falk GW. A coxib a day won’t keep the doctor away. Lancet. 2004;364:639-640.

32 Tuzun F, Unalan H, Oner N, et al. Multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of thiocolchicoside in acute low back pain. Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70(5):356-361.

33 Borenstein DG, Lacks S, Wiesel SW. Cyclobenzaprine and naproxen versus naproxen alone in the treatment of acute low back pain and muscle spasm. Clin Ther. 1990;12(2):125-131.

34 Basmajian JV. Acute back pain and spasm. A controlled multicenter trial of combined analgesic and antispasm agents. Spine. 1989;14(4):438-439.

35 van Tulder M, Koes B. Low back pain and sciatica. Clinical Evidence. 2004;11:1500-1533.

36 Fishbain D. Evidence-based data on pain relief with antidepressants. Ann Med. 2000;32:305-316.

37 Goldstein DJ. Duloxitene in the treatment of pain associated with diabetic neuropathy. Presentation to the 156th meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. San Francisco, May 17–22, 2003.

38 Wernicke JF. Duloxitene at doses of 60 mg qid and bid in effectiveness in the treatment of diabetic neuropathic pain. Presentation to the 56th annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. San Francisco, April 24–May 1, 2004.

39 Eisenberg E, et al. Lamotrigine for intractable sciatica: correlation between dose, plasma concentration, and analgesia. Eur J Pain. 2003;7:485-491.

40 Himovic IC, Beresford HR. Dexamethasone is not superior to placebo for treating lumbar radicular pain. Neurology. 1986;36:1593-1594.

41 Fast A, Alone M, Weiss S, et al. A vascular necrosis of bone following dexamethasone therapy for brain edema. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:983.

42 Igarashi T, et al. Exogenous tumor necrosis factor-alpha mimics nucleus pulposus-induced neuropathology: molecular, histologic, and behavioral comparisons in rats. Spine. 2000;25:2975-2980.

43 Murata Y, Onda A, Rydivik B, et al. Selective inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha prevents nucleus polposus-induced histologic changes in the dorsal root ganglion. Spine. 2004;29(22):2477-2484.

44 Korhonen T. Efficacy of infliximab for disc herniation-induced sciatica. Spine. 2004;29(19):2115-2119.

45 Galer BS, et al. Topical lidocaine patch relieves post-herpetic neuralgia more effectively than a vehicle topical patch: results of an enriched enrollment study. Pain. 1999;80:533-538.

46 Kaul MP, Herring SA. Superficial heat and cold. Phys Sports Med. 1994;22(12):65.

47 Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual. The lower extremities. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1983.

48 Kaul MP, Herring SA. Superficial heat and cold. Phys Sports Med. 1994;22(12):65.

49 Nadler SF, et al. Continuous low-level heatwrap therapy provides more efficacy than ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute low back pain. Spine. 2002;27:1012-1017.

50 Nadler SF, et al. Overnight use of continuous low-level heatwrap therapy for relief of low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:335-342.

51 Windsor RE, et al. Electrical stimulation in clinical practice. Phys Sports Med. 1993;21:85-93.

52 Hamza MA, et al. Effect of the frequency of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on the post-operative opioid analgesic requirements and recovery profile. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:S212.

53 Ghoname E, et al. Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation: an alternative to TENS in the management of sciatica. Pain. 1999;83:193-199.

54 Harte A, et al. The efficacy of traction for back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1542-1553.

55 Matthews JA. Dynamic discography: a study of lumbar traction. Ann Phys Med. 1968;9:275-279.

56 Onel D, et al. Computed tomographic investigation of the effect of traction on lumbar disc herniations. Spine. 1989;14(1):82-90.

57 Nachemson A, Elstrom G. Intravital dynamic pressure measurements in lumbar disc swelling: a study of common movements, maneuvers and exercises. Scand J Rehabil Med (Suppl). 1970;1:1-40.

58 Bridger RS, et al. Effect of lumbar traction on stature. Spine. 1990;15:522-524.

59 Berquist-Ullman M, Larsson U. Acute low back pain in industry. Acta Orthop Scand (Suppl). 1977;170:73.

60 Hall H, Iceton JA. Back school. Clin Orthop. 1983;179:10.

61 White AH. Low back injury prevention programs at Southern Pacific Railroads. Presented to the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. Paris, France; 1981.

62 Nachemson A. The lumbar spine: an orthopedic challenge. Spine. 1976;1:59.

63 McKenzie R. The lumbar spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy. Waikanae, NZ: Spinal Publication Ltd, 1981.

64 McKenzie RA. Manual correction of sciatic scoliosis. NZ Med J. 1972;76(484):194-199.

65 Krag M, et al. Internal displacement and distribution from in vitro loading of human thoracic and lumbar spinal motion segments: experimental results and theoretical predictions. Spine. 1987;12(10):1001-1007.

66 Shah JS, et al. The distribution of surface strain in the cadaveric lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1979;60(2):246-251.

67 Schnebel BE, et al. A digitizing technique for the study of movement of intradiscal dye in response to flexion and extension of the lumbar spine. Spine. 1988;13(3):309-312.

68 Fennell AJ, et al. Migration of the nucleus pulposus within the intervertebral disc during flexion and extension of the spine. Spine. 1996;21(23):2753-2757.

69 Razmjou H, et al. Intertester reliability of the McKenzie evaluation in assessing patients with mechanical low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(7):368-389.

70 Donelson R. Centralization phenomenon: its usefulness in evaluating and treating referred pain. Spine. 1990;15(3):211-213.

71 Wetzel FT, Donelson R. The role of repeated end-range/pain response assessment in the management of symptomatic lumbar discs. Spine J. 2003;3:146-154.

72 Snook SH, et al. The reduction of chronic, non-specific low back pain through the control of early morning lumbar flexion: three-year follow-up. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12(1):13-19.

73 Donelson R, et al. A prospective study of centralization of lumbar and referred pain: a predictor of symptomatic discs and annular competence. Spine. 1997;22(10):1115-1122.

74 Werneke M, Hart DL, Cook D. Descriptive study of the centralization phenomenon. Spine. 1999;24(7):676-683.

75 Donelson R, Grant W, Kamps C, et al. Pain response to sagittal endrange spinal motion: a prospective, randomized, multi-centered trial. Spine. 1991;16(Suppl):S206-S212.

76 Donelson R, Grant W, Kamps C. Pain response to sagittal end-range spinal motion: A multi-centered, prospective, randomized trial. Presented at the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine, Heidelberg, Germany, 1991.

77 Donelson R, Silva G, Murphy K. Centralization phenomenon: its usefulness in evaluating and treating referred pain. Spine. 1990;15:211-213.

78 Long A. The centralization phenomenon: Its usefulness as a predictor of outcome in conservative treatment of low back pain: A pilot study. Spine. 1995;20:2513-2521.

79 Stankovic R, Johnell O. Conservative treatment of acute LBP: a prospective randomized trial: McKenzie method of treatment vs. patient education in ‘mini back school.’. Spine. 1990;15:120-123.

80 Williams PC. Lesions of the lumbosacral spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1937;19(3):690.

81 Saal JA. The new back school prescription: stabilization training part II. Occup Med: State of the Art Reviews. 1992;7(1):33-42.

82 Akuthota V, Nadler S. Core strengthening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(1):S86-S92.

83 Nadler SF, et al. Hip muscle and balance in low back pain in athletes: influence of core strengthening. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2002;34:9-16.

84 Fritz JM, Erhard RE, Hagen BF. Segmental instability of the lumbar spine. Phys Ther. 1998;78:889-896.

85 Kavcic N, et al. Determining the stabilizing role of individual torso muscles during rehabilitation exercises. Spine. 2004;29(11):1254-1265.

86 Cholewicki J, et al. Intra-abdominal pressure mechanism for stabilizing the lumbar spine. J Biomech. 1999;32:13-17.

87 Gardner-Morse MG, Stokes I. The effects of abdominal muscle co-activation on lumbar spine stability. Spine. 1998;23(1):86-91.

88 Kaigle A, et al. Experimental instability in the lumbar spine. Spine. 1995;20(4):421-430.

89 Leinonen V, et al. Disc herniation-related back pain impairs feed-forward control of paraspinal muscles. Spine. 2001;26(16):E367-E372.

90 Rantanen J, et al. The lumbar multifidus muscle five years after surgery for a lumbar intervertebral disc herniation. Spine. 1993;18(5):568-574.

91 Hides J, et al. Multifidus muscle recovery is not automatic after resolution of acute, first-episode low back pain. Spine. 1996;21:2763-2769.

92 Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. The influence of low back pain on muscle activity and coordination during gait: a clinical and experimental study. Pain. 1995;64:231-240.

93 Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor controlled evaluation of transversus abdominus. Spine. 1996;21(22):2640-2650.

94 Cholewicki J, et al. Stabilizing function of trunk flexor–extensor muscles around a neutral spine posture. Spine. 1997;22(19):2207-2212.

95 Cole A, Herring S. The low back pain handbook: a guide for the practicing clinician, 2nd edn., Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2003:453-457.

96 Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual, volume II. The lower extremities. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1992.

97 Butler D, Gifford L. The concept of adverse mechanical tension in the nervous system. Physiotherapy. 1989;75(11):622-636.

98 Brieg A, Marions O. Biomechanics of the lumbosacral nerve roots. Acta Radiologica. 1963;1:1141-1161.

99 Butler DS. The sensitive nervous system. Australia: Noigroup Publications, 2000.

100 Sunderland S. The nerve lesion in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39:615-626.

101 Cole AJ, Herring SA. Low back pain: a guide for the practicing clinician. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 2003.

102 Matthews JA, et al. Back pain and sciatica: controlled trials of manipulation, traction, sclerosant, and epidural injections. Br J Rheumatol. 1987;26:416-423.

103 Crawford CM, Hannan RF. Management of acute lumbar disc herniation initially presenting as mechanical low back pain. J Manipul Physiol Ther. 1999;22(4):235-244.

104 Troyanovich SJ, et al. Low back pain in the lumbar intervertebral disc: clinical considerations for the doctor of chiropractic. J Manipul Physiol Ther. 1999;22(2):96-104.

105 Weitling J, Andary M, Holmes T, et al. Manipulation, massage and traction. Physical medicine and rehabilitation; principles and practice, 4th edn.. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 2005.

106 Longworth W, McCarthy PW. A review of research on acupuncture for the treatment of lumbar disc protrusions and associated neurological symptomatology. J Alternat Complemet Med. 1997;3(1):55-76.

107 Nachemson A, Morris JM. In vivo measurement of intradiscal pressure: discometry, a method for the determination of pressure in the lower lumbar discs. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1964;46:107.

108 Stillo JV, Stein AB, Ragnarsson KT. Low back orthoses. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 1992;3:57-94.