Medical problems

Introduction

General surgical operations are now performed on patients who are older, more frail and with significant and often multiple (medical) co-morbidities, so it becomes even more important to appreciate and consider these ‘medical’ conditions. Rates of deaths and complications after abdominal surgery have been the subject of a report by the Royal College of Surgeons of England (at: www.rcseng.ac.uk/publications/docs/higher-risk-surgical-patient). A high-risk patient is defined as one whose estimated risk of mortality is greater than 5%, and includes any patient over the age of 65 years undergoing major gastrointestinal or vascular surgery, and any patient over 50 years with diabetes mellitus or renal impairment. Recommendations include preoperative risk assessment with a tailored management plan directed by consultant surgeons and anaesthetists, and rapid identification and treatment of postoperative infection.

‘Medical’ disorders appear in surgical practice in four main ways:

• A pre-existing medical condition may precipitate a surgical admission because of exacerbation, progression or complications of the condition: for example, foot problems in diabetes

• A pre-existing medical condition may be made worse by operation. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, for example, general anaesthesia and postoperative sputum retention may precipitate life-threatening pneumonia

• A surgical condition may be complicated by an unrelated medical disorder. For example, a patient with rheumatoid arthritis on steroid therapy is vulnerable to impaired healing and recurrent infection

• An occult condition can become manifest under the stress of anaesthesia and operation. For example, perioperative or postoperative myocardial infarction can be caused by occult ischaemic heart disease

Cardiac and cerebrovascular disease

1 Ischaemic heart disease

The clinical manifestations of ischaemic heart disease are:

• Chronic stable exertional angina; previous myocardial infarction

Asymptomatic coronary artery disease may progress to infarction under anaesthetic and surgical stresses, including laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation, pain, hypoxia, rapid blood loss, anaemia, hypotension, hypocarbia and fluid overload. For major operations, general anaesthesia and spinal anaesthesia carry similar risks. Local anaesthesia, when practicable, is much safer.

Clinical problems

a: Stable angina and myocardial infarction more than three months previously There is usually little increased risk during operation and exercise tolerance is by far the most important indicator of the patient’s ability to tolerate anaesthesia and surgery. This can be assessed in the history (remembering that exercise tolerance may be limited by mobility problems rather than cardiorespiratory problems). Formal assessment on a treadmill may be helpful, and occasionally coronary angiography is required to fully assess cardiac risk.

b: Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) This is a term applied to a spectrum of conditions from unstable angina to non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) to ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Acute coronary syndrome associated with surgery usually occurs during the first few days after operation, particularly on the second to fourth postoperative nights, rather than during the operation. Typical chest pain is not always a feature and postoperative ACS may present ‘silently’ (i.e. painlessly) with otherwise unexplained hypotension, cardiac failure, arrhythmias or cardiac arrest, particularly in patients with diabetes. Diagnosis is made on the basis of at least two of the following: appropriate symptoms (particularly typical cardiac ischaemic pain); a significant rise in a cardiac biomarker, usually troponin; and ECG changes consistent with ischaemia (dynamic changes including ST depression, T-wave flattening or inversion) or infarction (ST elevation). It is always helpful to have a preoperative ECG for comparison which should be performed on all patients over 50 years of age and any with cardiac symptoms or signs.

2 Chronic heart failure (CHF)

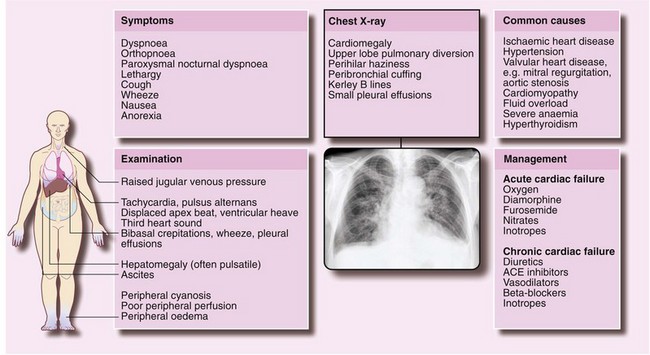

Patients with CHF should be optimised before major surgery, but there is still an increased mortality of up to 5%. The causes, symptoms and signs of cardiac failure are shown in Figure 8.1.

Fig. 8.1 The causes, symptoms and signs of cardiac failure

The chest X-ray is of a 60-year-old woman with a history of ischaemic heart disease. The signs indicate congestive heart failure. Note: some of these changes are subtle and do not reproduce well in illustrations

Clinical problems

a: CHF before operation Surgery should be postponed until treatment has been optimised and the clinical condition stabilised. Hasty preoperative diuretic therapy is dangerous because it may provoke intravascular volume depletion, hypotension and electrolyte abnormalities. Patients taking diuretics (and often ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists in addition) may have abnormalities such as:

• Hypokalaemia (usually due to potassium-losing diuretics prescribed without potassium supplements)

• Raised plasma urea and creatinine with hyperkalaemia (particularly if taking an ACE inhibitor and spironolactone)—the urea is often raised to a greater extent than creatinine indicating intravascular volume depletion

b: Decompensated heart failure developing during or after operation This problem results from poor tolerance of intravenous fluids, unaccustomed supine posture, myocardial infarction or ischaemia in the perioperative period, or arrhythmias (particularly atrial fibrillation) induced by the stresses of surgery and anaesthesia. Prompt and vigorous diuretic therapy with intravenous furosemide and nitrate is required to prevent worsening cardiac failure, hypoxia, renal failure or other potentially lethal complications. In addition, treatment of any precipitating factors should be instituted such as reducing cardiac stress by giving good pain relief. Postoperative cardiac failure is best managed in an intensive care unit, using a central venous pressure (CVP) line to guide fluid replacement.

Preoperative assessment of cardiac failure

Chest X-ray may demonstrate cardiomegaly and there may be signs of pulmonary oedema including upper lobe diversion, hilar congestion, septal Kerley B lines and pleural effusions (see Fig. 8.1). ECG may show an arrhythmia, myocardial ischaemia, ventricular hypertrophy, left bundle branch block or loss of R waves.

3 Cardiac arrhythmias

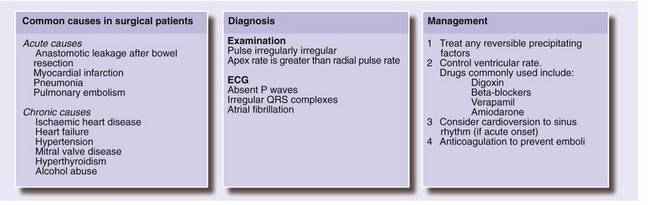

a: Atrial fibrillation (Fig. 8.2) Pre-existing (preoperative) atrial fibrillation is usually secondary to ischaemic heart disease but may be caused by mitral valve disease or thyrotoxicosis. Atrial fibrillation with a controlled ventricular rate (i.e. a pulse rate of less than 90 beats per minute at rest) causes minimal extra risk. An uncontrolled ventricular rate may cause perioperative heart failure. Atrial fibrillation (even with a controlled ventricular response) increases the risk of arterial embolism from any thrombus present in the left atrium. Adequate control of ventricular rate should be achieved before operation with beta-blocker and digoxin, occasionally supplemented with verapamil or amiodarone. Digoxin can be given intravenously if rapid control is necessary but potassium levels need to be monitored closely as digoxin given in the presence of hypokalaemia can lead to further arrhythmias. If the patient is anticoagulated with warfarin, there is a small risk of excessive bleeding at operation; stabilising the international normalised ratio (INR) between 1.5 and 2.5 may be the safest option. Another alternative is to stop warfarin and change to heparin.

Acute onset of AF postoperatively may be due to a major surgical (e.g. anastomotic leakage after bowel resection) or medical (e.g. pneumonia) complication (Fig. 8.2). If the onset of atrial arrhythmia (particularly atrial fibrillation) is associated with right bundle branch block on the ECG, this suggests a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism.

b: Bradycardia Bradycardia is common in young fit athletic patients and is not a problem. In patients taking beta-blockers or digoxin, if the apex rate is below 60 beats per minute, that day’s dose should be omitted and the regular dose reviewed.

c: Other arrhythmias Bifascicular block, in which conduction is impaired down two of the three main fascicles (right bundle plus anterior or posterior divisions of the left bundle, manifest by right bundle branch block and left axis deviation on the ECG), may progress to complete heart block (and low cardiac output) under anaesthesia. For these patients, a prophylactic temporary transvenous pacemaker should be considered before operation.

4 Hypertension

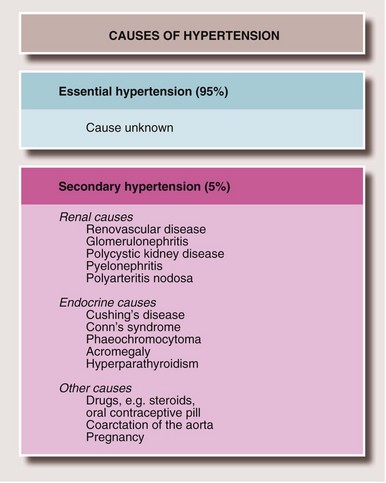

About one in four patients coming to surgery is either hypertensive or is receiving antihypertensive therapy. Most have ‘essential’ hypertension, but causes such as renal artery stenosis and phaeochromocytoma must be considered in patients presenting with raised blood pressure which has not been appropriately investigated. (For other causes see Fig. 8.3.) Undiagnosed renal artery stenosis puts the patient at risk of severe acute kidney injury if there is an episode of hypotension, and phaeochromocytoma of potentially fatal hypertensive crisis.

Clinical problems

a: Mild-to-moderate essential hypertension Patients with a systolic pressure of less than 180 mmHg and a diastolic less than 110 mmHg are at minimal risk of cardiac complications unless there is some other cardiovascular disease. Sometimes, anxiety about the operation contributes to the hypertension. A labile blood pressure or systolic hypertension at any time may, however, indicate widespread atherosclerosis.

b: Treated hypertension Most common antihypertensive drugs are ‘cardioprotective’ and should not be stopped prior to general anaesthesia. Despite the patient being ‘nil by mouth’ in the immediate preoperative period, the normal dose of oral antihypertensive drugs should usually be given with a small amount of water. Sudden withdrawal of antihypertensive drugs may cause rebound hypertension. Withdrawal of beta-blockers may trigger autonomic hyperactivity and lability of blood pressure. Postural hypotension may occur after operation, especially if there is dehydration.

c: Severe or poorly controlled hypertension If the diastolic BP is > 110 mmHg, then treatment needs to be instituted and any non-urgent operative procedure delayed. During anaesthesia the untreated hypertensive patient has a very labile BP and is at high risk of perioperative myocardial infarction, cardiac failure or stroke.

6 Valvular heart disease

Aortic stenosis

Clinical signs of aortic stenosis are:

• Slow rising upstroke of the carotid pulse

• A harsh ejection systolic murmur radiating into the neck

• Hyperdynamic apex beat indicating left ventricular hypertrophy. (Note: the apex beat is only displaced laterally if aortic stenosis coexists with aortic regurgitation or is complicated by cardiac failure)

If aortic stenosis is suspected, an echocardiogram will confirm the diagnosis and aid assessment of severity by measuring the aortic valve area, the gradient across the valve and an estimate of left ventricular systolic function.

Infective endocarditis and indications for antibiotic prophylaxis

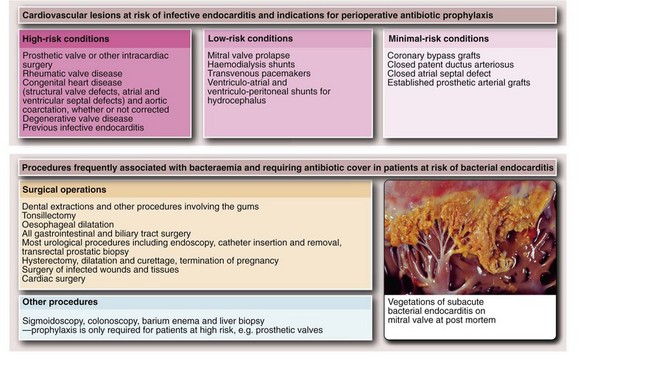

Streptococcus viridans is the most common causative organism of infective endocarditis. Other bacteria, such as coliforms or fungi, e.g. Candida, may also be responsible. Many types of operation and some invasive investigations cause transient bacteraemia. Although the incidence of infective endocarditis following such procedures is small, the consequences can be catastrophic. The efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics is not absolutely proven, but they are all that is available. The relative risks associated with various cardiac and valvular lesions are summarised in Figure 8.4. The procedures most likely to cause bacteraemia are also shown in Figure 8.4.

Respiratory diseases

Clinical problems

d Asthma

• Endotracheal intubation—increases airways sensitivity

• Increased airways secretions—caused by intubation or the autonomic side-effects of anaesthetic drugs such as muscle relaxants

• Dehydration—increases mucus viscosity

• Limitation of movement and posture because of pain—inhibits coughing to clear secretions

• The direct effects of other drugs, e.g. bronchoconstriction caused by beta-blockers or morphine-associated respiratory depression

In patients with asthma, the usual medication should be continued in the perioperative period, given via a nebuliser if necessary. Operations should be postponed during acute exacerbations.

Perioperative management of respiratory disease and high-risk patients

• Preoperative physiotherapy—helps prevent postoperative chest complications. Physiotherapy should include teaching the patient breathing exercises and correct posture

• Drug therapy—adjust to achieve optimum respiratory function. Theophyllines may be added in patients with asthma, and nebulised bronchodilator drugs (such as salbutamol) may improve the reversible component of COPD and help to prevent a perioperative exacerbation of asthma. Adequate hydration reduces the risk of retained secretions which might cause airways obstruction. Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended for COPD

• Encouragement of smokers to quit—should be started at the time of booking for elective surgery

• Alternative methods of anaesthesia—local, regional or spinal—should be considered for patients with chronic respiratory disorders, but are not necessarily the best solution. With the use of newer anaesthetic drugs and techniques, patients may be better off with endotracheal intubation and ventilation using short-acting muscle relaxants. These techniques allow good bronchial toilet at the end of operation. Certain abdominal operations are technically more difficult under spinal anaesthesia, for example if a patient with chest trouble coughs persistently during the procedure; general anaesthesia avoids this

• Early postoperative physiotherapy—aims to enhance deep breathing, coughing and general mobility, reducing the incidence of respiratory complications

Gastrointestinal disorders

Hepatic disorders

Clinical problems

Most previously jaundiced patients will have suffered acute infective hepatitis (hepatitis A) and this poses no risk to staff because the infective agent does not cause a chronic carrier state. In contrast, lifetime chronic hepatitis develops in 5–10% of those infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and in 80% of those infected with HCV. These diseases should be suspected if the illness associated with the previous jaundice was prolonged or serious. Jaundice contracted in developing countries should be regarded with suspicion because hepatitis B and C are often endemic. Hepatitis C causes a high long-term rate of cirrhosis, although it often develops slowly over many years. Hepatitis B and C are also common among men who have sex with men and intravenous drug abusers who share syringes. The history should include questions to determine whether the patient falls into a high-risk group. Clinical examination should include a search for intravenous injection sites characteristic of drug abuse. In high-risk patients, screening for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis C antibody should be performed (see Ch. 3).

b Presence of obstructive jaundice

Surgery in this situation is usually performed to relieve an obstruction in patients where endoscopic stenting of the bile ducts is inappropriate, has failed or is unavailable. This surgery carries a number of special risks and management problems which are described in Chapter 18. These include ascending cholangitis, clotting disorders, deep vein thrombosis and acute renal failure.

c The patient with known hepatitis

Patients with any form of hepatitis, whether viral or alcoholic, tolerate general anaesthesia and surgery badly and there is a definite mortality risk. Surgery should be avoided unless essential. If alcoholism is suspected, a CAGE questionnaire (Box 8.1) should be completed. Positive answers to two or more of the four questions suggest a drinking problem.

d The patient with known cirrhosis

• Defective synthesis of clotting factors and thrombocytopenia

• Electrolyte disturbances (particularly hyponatraemia)

• Defective energy metabolism (gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis)

• Abnormal drug metabolism and distribution (due to hypoalbuminaemia)

The main postoperative complications of cirrhosis are excessive bleeding, defective wound healing, hepatocellular decompensation leading to encephalopathy, and susceptibility to infection.

Excessive bleeding results from several factors:

• Defective synthesis of clotting factors (all but factor VIII are synthesised in the liver)

• Thrombocytopenia (due to hypersplenism and depressed platelet production)

• Abnormal polymerisation of fibrin

• Portal hypertension (greatly expanded intra-abdominal venous network under high pressure). This, together with numerous vascular adhesions, makes dissection in the abdominal cavity tedious, difficult and bloody

Portal hypertension may initially be discovered because of ascites or splenomegaly or an acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage from oesophageal varices, gastroduodenal ulcers, Mallory–Weiss tears or gastric erosions. If a patient with known oesophageal varices requires an operation, preoperative endoscopic assessment is important and sclerotherapy or banding may be appropriate.

Preoperative assessment and management

Preoperative blood tests for patients with liver disease are listed in Box 8.2. If the prothrombin ratio is prolonged, intravenous vitamin K injections are given for several days before operation. If this fails to correct the abnormal clotting (as in severe hepatocellular impairment), it is important to liaise with a haematologist who may recommend perioperative administration of fresh-frozen plasma or prothrombin complex concentrate (e.g. Octaplex or Beriplex), containing factors II, VII, IX, X, protein C and protein S. If the patient is thrombocytopenic, platelet transfusion may also be required.

Renal disorders

Renal impairment is commonly encountered in general surgical patients. There is impaired homeostasis of fluid and electrolytes and reduced excretion of nitrogenous compounds. The risk of perioperative complications increases with the degree of renal impairment. Patients fall into two groups: mild and severe chronic renal failure (CRF). Acute renal failure (acute kidney injury) is usually a postoperative complication, often with several contributory causes including hypovolaemia, and is described in Chapter 12. Patients with pre-existing renal disease are particularly vulnerable to progress to acute renal failure (‘acute-on-chronic renal failure’).

Clinical problems

a Mild/moderate chronic renal failure (CKD stage 1–3, eGFR > 30 ml/min)

• Impaired excretion of drugs—drugs handled by the kidney must be given in smaller doses or less frequently, as documented in official drug formularies. In practice, digoxin and gentamicin pose the main problems

• Fluid and electrolyte homeostasis—only becomes a problem if fluid balance is not monitored carefully in the perioperative period. Monitoring should include regular checks of plasma urea, electrolytes and creatinine, especially if the patient is receiving diuretic therapy

• Reduction in renal reserve—even a small increase in plasma creatinine implies a significant reduction in renal reserve. For example, major reconstructive surgery to the abdominal aorta in a patient with mild renal impairment may interfere with renal function because of aortic cross-clamping near the renal arteries. This is exacerbated by transient hypotension caused by blood loss. The lack of renal reserve in these patients may then progress to acute renal failure

b Severe chronic renal failure (CKD stage 4–5, eGFR < 30 ml/min)

These patients are usually under the care of specialist physicians who should be involved in perioperative management. Patients may be receiving regular haemodialysis or ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; in such patients, surgery may be for renal transplantation (see Fig. 8.5).

The main perioperative problems of severe CRF are:

• Fluid overload—caused by impaired glomerular filtration and may require correction with large doses of diuretics, fluid restriction and haemofiltration if necessary

• Regulation of plasma osmolality—this is disordered in patients with severe CRF who are particularly vulnerable to hypo- and hypernatraemia. Care must be taken that the sodium content of intravenous fluids is appropriate

• Hyperkalaemia—this is a particular risk in advanced CRF. Patients with lesser degrees of CRF are vulnerable to an increase in potassium load (due to transfusion, tissue damage or hypoxia) or changes in glomerular filtration rate (caused by cardiac failure or hypotension). Hyperkalaemia may cause cardiac arrest and susceptibility to this may be assessed by monitoring the ECG. To minimise this risk, the preoperative plasma potassium level should be stabilised below 5.0 mmol/L, but in chronic hyperkalaemia a plasma potassium up to 6.5 mmol/L rarely causes problems.

• Metabolic acidosis—this tends to develop in chronic renal failure but it is usually compensated by respiratory alkalosis. This compensation is disrupted by general anaesthesia and also by additional metabolic acidosis resulting from tissue ischaemia or hypoxia

• Chronic normochromic normocytic anaemia—this results from decreased erythropoietin production by the kidney. Cardiovascular function is usually well adapted to this anaemia and preoperative transfusion is unnecessary. If the haemoglobin concentration is substantially below 10 g/dl, the patient is usually treated with erythropoietin

Diabetes mellitus

• Some complications of diabetes are associated with a higher perioperative risk. These are summarised in Box 8.3

• Stress (including surgery, trauma and infections) causes increased production of catabolic hormones which oppose the action of insulin (see Ch. 2), making diabetic control more difficult

• General anaesthesia, surgery, deprivation of oral intake and postoperative vomiting disrupt the delicate balance between dietary intake, exercise (energy utilisation) and diabetic therapy

• Diabetic ketoacidosis is a cause of elevated leucocyte count and raised amylase level, which may be confusing in the diagnosis of patients presenting with an acute abdomen. Indeed, ketoacidosis may sometimes present with abdominal pain

• There is a greater risk of hospital-acquired infection, which may be elusive as a cause of deterioration

• Episodes of cardiac ischaemia and infarction may be painless

• There may be reduced renal reserve or more overt evidence of renal impairment

Clinical problems

a Insulin-dependent diabetes

• Establish good diabetic control before operation

• Give insulin as a continuous intravenous infusion during the operative period

• Give an infusion of dextrose (glucose) throughout the operative period to balance the insulin given and to make up for lack of dietary intake

• Add potassium to the dextrose infusion

• Monitor blood glucose and electrolytes frequently throughout the operative and early postoperative period

A typical management protocol is given in Box 8.4 and a recommended insulin infusion regimen (a ‘sliding scale’) in Box 8.5. The key is to adjust the insulin dose hourly according to blood glucose results.

Musculoskeletal and neurological disorders

Rheumatoid arthritis

• Normochromic normocytic anaemia—common in chronic inflammatory disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis, although less common now that active inflammation is better controlled with modern drug therapy. The anaemia is refractory to iron therapy and there is no benefit from preoperative transfusion unless haemoglobin concentration is < 8 g/dl, or the patient is symptomatic

• Gastrointestinal disorders—most will be taking NSAIDs, which together with long-term steroid therapy, predispose to peptic ulceration and perforation. Chronic low-grade bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract may exacerbate the existing anaemia in these patients. Operative stress may also precipitate acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage. NSAIDs may contribute to kidney injury

• Long-term steroid therapy—may result in adrenal insufficiency under stress

• Other medications—powerful drugs now used include chloroquine, methotrexate, sulfasalazine and cytokine inhibitors. Refer to standard formularies for potential problems

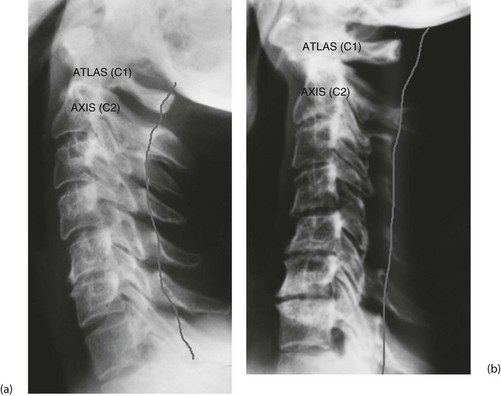

• Odontoid subluxation (Fig. 8.7)—if rheumatoid arthritis involves the atlanto-axial joint, the transverse ligament may be destroyed, allowing the odontoid process to sublux. During general anaesthesia, the protective reflexes are lost. If the neck is hyperextended during intubation, there is a serious risk of injury to the spinal cord by the unrestrained odontoid

Haematological disorders

Bleeding disorders

• Excessive bleeding from simple cuts, previous surgery, dental extractions or childbirth

• Current use of anticoagulant drugs or anti-platelet drugs (aspirin and clopidogrel)

• A family history of bleeding disorders

• Intercurrent haematological or liver disease, cystic fibrosis or other malabsorption syndromes

Recognising and treating a clotting problem before operation is vital because runaway haemorrhage can easily occur, causing clotting factor depletion. At this point, bleeding may be impossible to control even with transfusion of clotting factors.

Clinical problems of bleeding disorders

a: Inherited clotting disorders Haemophilia occurs in males. The disorder is an X-linked deficiency of factor VIII or, less commonly, factor IX. Specific antihaemophilic factors are administered before operation and for up to 2 weeks afterwards until the danger of secondary haemorrhage is past. Von Willebrand’s disease is an autosomal dominant condition with abnormalities of both factor VIII and platelet function. It is managed with replacement of the specific factors.

b: Anticoagulant therapy The management of patients on warfarin and other anticoagulants is described earlier in this chapter and in Chapter 12.

c: Liver disease Bleeding disorders in cirrhosis are described earlier in this chapter, and disorders in the jaundiced patient are described in detail in Chapter 18.

d: Aspirin and clopidogrel therapy Aspirin has an irreversible inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation which persists clinically for at least 10 days. The effect is reversed only when the affected platelets have been replaced. Most NSAIDs act on platelets in a similar but less profound way. High doses of intravenous penicillin cause a similar but short-lived effect. Aspirin ingestion, even in low doses, tends to cause oozing during and after operation, although this is rarely serious. For major elective arterial surgery, aspirin should ideally be stopped about 2 weeks before operation.

Psychiatric disorders

Obesity

Gross obesity carries 2–3 times the risk of perioperative death or morbidity, as outlined in Table 8.1. Whenever possible, weight should be reduced before operation, particularly if it is not urgent. Referral to a dietician may be helpful although self-help groups often provide stronger motivation. Preoperative investigations for obese patients include blood glucose measurement, respiratory function tests and ECG, even if the patient is asymptomatic.

Table 8.1

Surgical complications of obesity

| Complication | Factors |

| Cardiopulmonary complications such as cardiac failure and chest infections | Predisposing factors are atherosclerosis, increased demands on the cardiovascular system, decreased chest wall compliance, inefficient respiratory muscles and shallow breathing |

| Wound complications such as infection, dehiscence | Poor-quality abdominal wall musculature with fat infiltration. Large ‘dead space’ in which fat predisposes to haematoma formation |

| Venous thromboembolism—increased risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism | Poor peripheral venous return; delayed return to normal mobility |

| General anaesthesia complications | Anatomical problems, e.g. intravenous cannulae difficult to insert and intubation more difficult. Clinical signs of dehydration and hypovolaemia are more difficult to elicit Physiological problems: metabolic, e.g. altered distribution of drugs |

| Predisposition to various medical disorders | Hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, type 2 diabetes, gallstones, gout |

| Operative difficulties | Operations take longer because of difficult access and obscuring of vital structures by fat. Leads to a higher incidence of anaesthetic and surgical complications, particularly of the wound |

| Problems of manual handling | Weight and size limitations of standard equipment including CT scanners, operating tables, beds Need for hoists, powered beds Risks to staff involved in lifting and handling |

Chronic drug therapy

Many drugs prescribed for long-term treatment of ‘medical’ conditions can complicate management of the surgical patient. Note that the risk of stopping long-term medication before surgery is often greater than the risk of continuing it throughout. Drugs that should not normally be stopped include anticonvulsants, antiparkinsonian drugs, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, bronchodilators, cardiovascular drugs, glaucoma drugs, immunosuppressants, drugs of dependence and thyroid or antithyroid drugs. The most important of these commonly encountered in practice are summarised in Box 8.6.