Chapter 188 Medical Management of Neck and Low Back Pain

Back pain is common and costly. It was the most frequent type of pain reported by U.S. respondents in the 2002 National Health Information Survey (NHIS), with more than one fourth of adults reporting an episode of low back pain lasting at least 1 day in the preceding 3 months.1 In the NHIS survey, neck pain ranked third, with 13.8% of persons reporting at least a 1-day episode. Back pain ranks in the top five reasons for visits to primary care physicians in the United States.1,2 Up to 71% of the adult population may experience a significant episode of neck pain in their lifetimes.3 Approximately 2% of the U.S. workforce sustains a compensable back injury each year.4 The direct cost of health care attributed for low back pain exceeds $25 billion dollars in the United States.5 The largest proportion of direct medical costs for back pain is spent on physical therapy (17%), followed by pharmacy (13%) and primary care physician visits (13%).6 Indirect costs related to lost productivity in the workplace or homes are substantially higher than the direct costs of back pain.6

An appreciation of the benign short-term prognosis of acute nonradicular low back pain is fundamental to the management of these patients. Most patients recover within 1 month and more than 90% of patients have returned to work by 3 months.7 However, about one fourth of patients have persistent symptoms at 3 months and about 20% have substantial limitations of activity at 1 year.8,9 Clearly, an important objective of medical treatment should be to reduce the likelihood of progression from acute symptoms to chronic pain and functional impairment. The primary determinants of persistent disability at 12 months are psychosocial in nature.8,10 In fact, psychosocial variables have been shown to be superior to structural findings or discography as predictors of both long- and short-term disability, duration of symptoms, and health care visits for back pain.11 High levels of psychological distress, depressive mood, and somatization are well established as risk factors for transition from acute back pain to chronicity.8,12 Coping styles characterized by catastrophizing or fear avoidance are suspected but less well established as predisposing to the development of chronic symptoms. Failure to recognize these psychosocial issues in patients with low back pain will frustrate even the most well-conceived medical management strategy.

Etiology of Back and Neck Pain

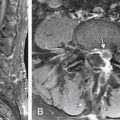

The specific anatomic etiology of nonradicular spinal pain is often ambiguous. Up to 85% of patients have pain that cannot be assigned to a particular pain generator.13 “Abnormal” findings on plain radiographs, including spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, facet joint degenerative changes, Schmorl nodes, and mild scoliosis, are common in asymptomatic persons.14 Radiography of the lumbar spine in patients with back pain of at least 6 weeks’ duration (mean, 10 weeks) has been shown to increase patient satisfaction without any improvement in functional outcome or severity of pain.15 The addition of lateral dynamic flexion-extension radiographs to the initial evaluation of patients with low back pain rarely provides information that alters clinical management, at the expense of significant additional cost and radiation exposure.16 Disc abnormalities are found on MRI in more than 50% of asymptomatic persons by age 40 years and include degenerative disc bulging and protrusions as well as Schmorl nodes.17 The lack of specificity of clinical symptoms and signs for the multiple potential sources of spinal pain—ligaments, facet joints, discs, paravertebral musculature—confounds the attempt to attribute symptoms to radiographic findings. In some patients previously categorized as having nonspecific pain, interventional diagnostic techniques, including discography, facet joint medial branch block or injection, and sacroiliac joint injection, may suggest a specific pathoanatomic etiology. However, these studies have high false-positive rates, particularly in patients with psychosocial issues, and fail to reliably predict the success of specific surgical or interventional treatments.11,14

Cancer and infection are serious but fortunately uncommon specific causes of back pain found in 0.7% and 0.01%, respectively, of patients presenting in a primary care setting.13 The spine is one of the most common sites of metastasis, most commonly arising from breast, lung, prostate, or kidney primary tumors.18 Ankylosing spondylitis is identified in about 0.3% of patients with low back pain, typically younger men.14 Acute or subacute vertebral compression fractures are identified in about 4% of patients. A variety of nonspinal conditions may present with symptoms that mimic spine disorders. These include common musculoskeletal problems such as greater trochanteric bursitis and osteoarthritis of the hip, as well as visceral problems such as kidney stones, aortic aneurysms, and peptic ulcers.

The American College of Physicians and American Pain Society’s recently published evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the management of back pain suggests a focused history and physical examination should permit placement of patients with back pain into one of three broad categories: nonspecific low back pain, back pain with radicular symptoms including lumbar spinal stenosis, and back pain associated with another specific spinal cause.13 Diagnostic imaging is recommended only when a serious etiology (cancer or infection) is suspected or when surgical or other interventional treatment is imminent (Box 188-1). For patients with nonspecific, nonradicular back pain, the guideline incorporates education, activity, physical therapy, medications, and a range of nonpharmacologic therapies.

Recommendation 1: Conduct a focused history and physical examination to categorize patients into one of three categories: nonspecific low back pain, back pain potentially associated with radiculopathy or spinal stenosis, or back pain potentially associated with another specific spine cause. Evaluate for psychosocial risk factors which predict risk for chronic, disabling low back pain.

Recommendation 2: Imaging or other diagnostic tests should not be obtained routinely in patients with nonspecific low back pain.

Recommendation 3: Perform diagnostic imaging and testing for patients with low back pain when severe or progressive neurologic deficits are present or when serious underlying conditions are suspected on the basis of history and physical examination.

Recommendation 4: Evaluate patients with persistent low back pain and signs or symptoms of radiculopathy or stenosis with MR (preferred) or CT only if they are potential candidates for surgery or epidural steroid injection.

From Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med 147:478–491, 2007.

Medical Treatment Options

Prevention

In view of the enormous personal, societal, and financial burden of back pain, numerous preventive approaches have been investigated. A recent systematic review of prospective, controlled trials of interventions to prevent back pain in working-age adults identified 20 trials that met inclusion criteria.19 Only exercise, in seven of eight trials, was found effective in preventing self-reported episodes of back pain. A variety of exercise approaches were used, including stretching, strengthening of abdominal, back, and leg muscles, and general conditioning. Interventions found ineffective in reducing back pain episodes included stress management, shoe inserts, back supports, ergonomic and back education, and reduced lifting programs. Although evidence for efficacy in prevention of back pain is lacking, smoking cessation and reduction to appropriate weight for height should be encouraged because both smoking and obesity have been associated with increased severity of back symptoms.20,21

Exercise and Physical Therapy

For patients with acute (<4 weeks) back or neck pain, there is little evidence that formal physical therapy is necessary.22 The best advice for such patients is probably to continue with their usual activities as tolerated. In fact, early referral to physical therapy prolonged duration of symptoms compared with patients simply advised to stay active.23 For patients with persistent chronic neck or back symptoms, however, exercise therapy is the cornerstone of medical treatment to decrease pain and restore function and mobility. An impairment-based manual physical therapy and exercise program resulted in clinically and statistically significant short- and long-term improvements in pain, disability, and patient-perceived recovery in patients with mechanical neck pain compared with a program comprising advice, mobility exercise, and subtherapeutic ultrasonography.24 Similarly, a recent meta-analysis found that exercise therapy was effective at decreasing pain and improving function in adults with chronic low back pain and may improve work absenteeism in patients with subacute symptoms.22 Unfortunately, studies comparing different exercise approaches, including stabilization, McKenzie, Pilates, and general aerobic conditioning, are insufficient to strongly recommend a single approach in a particular subset of patients. However, two recent studies have suggested that selection of a physical therapy approach based on diagnosis or mechanical assessment is more effective than general nonspecific exercise advice.25,26

General aerobic conditioning is often recommended for patients with chronic neck or back pain. The sense of well-being and accomplishment acquired from a planned aerobic exercise program such as walking, running, cycling, or swimming creates a positive treatment milieu and further establishes the extent of patient motivation and commitment to the overall treatment plan. Patients participating in an aerobic exercise program have been shown to receive fewer prescriptions for pain, were given fewer physical therapy referrals, and had improved mood states and lessened depression.27

Evidence suggests the superiority of neck stabilization exercises, with some advantages in pain and disability outcomes, compared with isometric and stretching exercises in combination with physical therapy agents (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, continuous ultrasonography, and infrared irradiation) for the management of neck pain.28 There is moderate evidence that lumbar stabilization exercises are effective in improving pain and function in a heterogeneous group of patients with chronic low back pain.29 Unfortunately, available studies are unable to define a specific subgroup of patients with chronic low back pain most suitable for this exercise approach. The current evidence suggests that in the short term, lumbar extensor strengthening exercise administered alone or with cointerventions is more effective than no treatment and most passive modalities in improving pain, disability, and other patient-reported outcomes in chronic low back pain.30

Yoga and Pilates exercises have grown in popularity over the last decade and represent two mind-body exercise interventions that address both the physical and mental aspects of pain with core strengthening, flexibility, and relaxation. There has been a gradual trend toward inclusion of these nontraditional exercise regimens into treatment paradigms for back pain, although few studies critically examining their effects have been published.31 A retrospective analysis of two randomized, controlled trials and one case-controlled series found significant improvement in general function and pain with the Pilates approach in treating nonspecific chronic low back pain in adults. However, as with other exercise paradigms, currently available data do not predict which groups of patients might be best managed with this approach.32

The McKenzie method is a unique and comprehensive approach to neck or low back pain that includes both assessment and intervention. The assessment is designed to detect a directional preference, which refers to a particular direction of movement or sustained posture that causes symptoms to centralize, decrease, or be abolished. Centralization is defined as the sequential and lasting abolition of all distal referred symptoms and subsequent abolition of any remaining spinal pain in response to a single direction of repeated movements or sustained postures. The finding of centralization has positive prognostic value, provided treatment is guided by assessment findings. Noncentralization is a strong predictor of poor prognosis and correlates well with “nonorganic” signs.33 In limited clinical trials, McKenzie-based therapy produces results comparable with those of stabilization or strengthening programs.34,35

Aquatic exercise is potentially beneficial to patients suffering from chronic low back pain and pregnancy-related low back pain.36 Patients with barriers to land-based programs, including lower extremity joint disorders and obesity, are often able to exercise actively in the pool.

Medication

In addition to passage of time, participation in an active exercise program, and use of nonpharmacologic treatments, medicinal treatment is an important component of medical management of neck and back pain. Medications with reasonable evidence of short-term effectiveness for low back pain include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, skeletal muscle relaxants (for acute low back pain), and tricyclic antidepressants (for chronic low back pain).37 Evidence suggests that NSAIDs are no more effective than pure analgesics for low back pain.38

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen (acetyl-para-aminophenol [APAP]) has analgesic and antipyretic properties comparable with aspirin, but its anti-inflammatory effects are weak. APAP’s analgesic effects and excellent safety profile make it a reasonable first-line medication for acute back and neck pain. Peak analgesic effects are typically noted from 30 to 60 minutes after ingestion. APAP is relatively inexpensive and produces fewer adverse reactions than NSAIDs. Although recent systematic reviews have found APAP as effective as NSAIDs in the treatment of back pain, in other musculoskeletal disorders, particularly osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, NSAIDs provide better pain relief.39 The accepted oral dose of acetaminophen is 325 to 1000 mg every 4 to 6 hours, not to exceed 4000 mg in 24 hours. The most serious adverse effect of acute acetaminophen overdosage is hepatotoxicity. Risk of hepatotoxicity is increased in patients with known liver disease, heavy alcohol use, or severe fasting states due to vomiting, diarrhea, or severe flu. A major current concern is accidental overdosage in patients who take APAP in addition to a prescription analgesic containing APAP. In adults, serious hepatotoxicity may occur from a single dose of 10 to 15 g.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

The NSAIDs relieve both pain and inflammation and are a reasonable choice as a first-line agent for the control of acute low back or neck pain in patients without significant risk factors for adverse effects. A recent systematic review of randomized, controlled trials found NSAIDs were effective for short-term relief of acute and chronic back pain, but no more effective than acetaminophen.40 This review and others have concluded that all NSAIDs, including cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, are equally effective in treating low back pain.41 Because efficacy among these drugs is comparable, the choice of a particular NSAID is based on cost and safety, particularly in patients at higher risk for adverse effects. GI toxicity is the major limiting factor to NSAID therapy, with serious ulcer complications (bleeding or perforation) seen in about 1.5% of treated patients. All NSAIDs may increase the risk of a cardiovascular event in patients at risk. The American Heart Association recommendations for drug therapy for musculoskeletal pain in patients at cardiovascular risk favor pure analgesics as the drugs of first choice, with nonacetylated salicylates such as salsalate or non-COX-2–selective drugs (particularly naproxen) as alternative choices.42 Other potential side effects include renal failure, tinnitus, fluid retention, and high blood pressure. Although some variability with regard to adverse effects has been recognized, all NSAIDs can cause central nervous system side effects such as drowsiness, dizziness, and confusion. If an NSAID is used, frequent clinical and laboratory monitoring for adverse renal or GI reactions is mandatory. Risk factors for NSAID toxicity include age older than 65 years, known or suspected cardiovascular disease, history of congestive heart failure, history of recent GI bleed or ulcer, kidney disease, hepatic cirrhosis, and history of aspirin-induced respiratory disease. NSAIDs should also be avoided in patients in the third trimester of pregnancy. Acetaminophen is relatively inexpensive with a superior safety profile to NSAIDs and is the first choice in such high-risk patients.43

Oral Steroids

Medications such as prednisone and methylprednisolone are potent corticosteroids with strong anti-inflammatory properties. Corticosteroids are effective in the treatment of inflammatory reactions associated with allergic states, rheumatic and autoimmune diseases, and respiratory disorders. Studies designed to investigate the use of oral steroids in the setting of low back or neck pain are limited. A placebo-controlled trial of a single dose of intravenous methylprednisolone in acute low back pain demonstrated no significant improvement in the steroid-treated group.44 Despite lack of any published evidence for efficacy, oral corticosteroids are widely prescribed to treat acute back or neck pain, particularly with radicular symptoms. Dosage schedules vary, but 7 to 14 days of tapering from a prednisone equivalent dose of 40 to 60 mg is typical. Patients with diabetes should be warned about steroid-induced hyperglycemia. The risk of steroid-induced osteonecrosis is a concern, but the risk appears low.

Antidepressant Medications

Antidepressants are often used in the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain as well as in neuropathic pain syndromes. Although there is no evidence to support their use in acute pain, the efficacy of antidepressants in patients with chronic low back pain is reasonably well established. Antidepressant drug therapy may be beneficial in these patients because up to one third of them also experience depression. However, treating nondepressed patients with tricyclic antidepressants has been shown to significantly improve neuropathic-type pain compared with placebo, but without an improvement in functional status.45 In contrast to tricyclic antidepressants, newer selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have not been demonstrated to be effective in treating back or neck pain.

Opioids

Since the initial report of Portenoy and Foley describing the use of long-term opioid analgesics in treating nonmalignant pain, opioids have gained increasing acceptance as an appropriate therapy for carefully selected patients with spinal pain.46 A recent study found 66% of patients treated in an orthopaedic spine practice received opioids, 25% for longer than 3 months.47 Despite increasing use, concerns about long-term opioid use in chronic nonmalignant pain remain, including risk of abuse, tolerance, and dependence as well as fear of disciplinary action by medical boards for prescribing physicians. In addition, studies of opioids in chronic back pain have inconsistently demonstrated improvement in functional status in addition to pain. Furthermore, long-term trials demonstrating sustained benefit with acceptable toxicity are few.

Opioids are available in sustained-release (sustained release [SR], controlled release [CR], extended release [ER]) forms with prolonged analgesic effect lasting up to 72 hours (fentanyl transdermal), or short-acting immediate-release preparations with analgesic effect for 2 to 6 hours.48 Most opioids undergo first-pass metabolism in the liver, by oxidation involving cytochrome P-450 enzymes (fentanyl, oxycodone) and/or by glucuronidation (morphine, oxymorphone).49 Differences in opioid efficacy are partially related to genetic factors involving cytochrome P-450 alleles. Other clinically important differences in opioid metabolism are related to age, sex, and ethnicity.

Although most opioids share common pharmacologic properties and mechanisms of action, unique properties of selected agents are clinically relevant. Methadone is an effective and relatively inexpensive, long-acting opioid analgesic with unique pharmacokinetics and mechanism of action. In addition to activity at the mu-opioid receptor like other agents, methadone inhibits serotonin uptake and antagonizes the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, potentially offering superior efficacy for neuropathic pain. However, because of a disparity between duration of analgesic effect (8 hours) and drug half-life (24–26 hours), initiating treatment with methadone must be done cautiously, with increments in the dose at 5- to 7-day intervals.50 Tramadol and its active metabolite exert their analgesic effect as both mu receptor agonists and by nonopioid inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake.49 Coadministration of tramadol with antidepressants of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor class risks development of a “serotonin syndrome” manifested by hyperactivity, agitation, fever, seizures, and even death.51 Finally, meperidine has a half-life of 3 hours, but the half-life of its inactive metabolite normeperidine is about 20 hours. Repeated administration of meperidine for pain relief may result in toxic levels of normeperidine, particularly in elderly patients. Clinical manifestations of normeperidine toxicity include tremors, hallucinations, and seizures.52

Several recent reviews of both short- and long-acting opioids in chronic low back pain have concluded that opioids are safe and effective, at least in the short term, in reducing symptoms.48,53,54 In general, among patients able to tolerate opioid therapy, about one third can be classified as excellent responders, one third as “fair” responders, and one third as nonresponders.48 Magnitude of pain reduction in these trials as assessed by visual analogue scale ranges from 2.0 to 3.8. In most studies approximately one third of opioid-treated patients withdraw because of intolerable adverse effects. Significant improvement in pain and function, assessed by the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) for low back pain, was sustained up to 1 year in a case series of patients with refractory chronic low back pain treated with opioids.55 Two recent trials found little evidence of tolerance or addiction and abusive behavior in patients with back pain treated with long-term opioids.47,56 However, another recent systematic review of opioid treatment in patients with chronic low back pain found “aberrant medication-taking behavior” in 5% to 24% of patients.53 However, the authors noted that the studies reviewed failed to control for aberrant behavior related to inadequate pain control (“pseudoaddictive behavior”).

Unlike other analgesics, including acetaminophen or NSAIDs, opioids are not toxic to the liver, kidneys, brain, or other organs. Common adverse effects include constipation, nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, sedation, and sweating.48 Unlike most other adverse effects, tolerance does not develop to opioid-induced constipation. Prophylactic treatment with laxatives and stool softeners should be considered in all patients beginning opioid therapy. Although concerns have been raised whether opioid-treated patients can drive safely, a systematic review found no impairment of psychomotor abilities of opioid-dependent patients.57 The best approach is probably to counsel patients to be aware of possible transient cognitive impairment and not to drive or engage in dangerous work situations, particularly when initiating opioid treatment or increasing the dose. In men, androgen deficiency manifested by low libido, erectile dysfunction, and lack of energy is a concern because opioids suppress gonadotropin-releasing hormone.58 Whether long-term opioid therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone suppression results in bone loss (“opioid osteoporosis”) is uncertain.

Tolerance, the need to increase opioid dosage to maintain the same therapeutic effect, appears to be uncommon in patients with low back pain treated with opioids.47,55 Physical dependence on opioids and addictive behavior are often confused. Dependence is a state of physiologic adaption characterized by withdrawal symptoms when the drug is abruptly discontinued. Most opioid-treated patients become dependent within a few weeks of initiating treatment. Addiction, on the other hand, represents a maladaptive disorder characterized by compulsive use of an opioid despite biologic psychological, or social harm.48 In the absence of a prior history of substance abuse, the risk of addiction in opioid-treated patients with low back pain appears low. When opioid therapy is considered in patients with chronic spinal pain, a careful assessment of risk for abuse, misuse, or diversion should be performed. This assessment should include evaluation for known risk factors, including smoking, psychiatric disorders, and personal history or family history of substance abuse.59 In patients on long-term opioid therapy, risk management for abuse should include use of a prescription monitoring program as is available in most states, an opioid treatment agreement outlining risk, benefits, and behavior expectations to the patient beginning therapy, compliance monitoring with urine drug screens or pill counts, and regular assessment of the “Four A’s” of pain treatment: analgesia, activities of daily living, adverse events, and aberrant drug-taking behavior.59

Muscle Relaxants

Muscle relaxants are widely used to treat low back and neck pain, presumably to address muscle spasm as the primary source of spinal pain or as a secondary phenomenon superimposed on underlying spine pathology. These drugs, which include benzodiazepine and nonbenzodiazepine antispasmodics and antispasticity agents, are believed to act centrally at the brainstem or spinal cord level.60 Systematic reviews of muscle relaxants for nonspecific low back pain have concluded that all are comparably effective in providing early, short-term pain relief compared with placebo, but with significant risk of side effects. In acute back pain, the treatment benefit appears greatest in the first few days and declines rapidly after the first week of symptoms. There is limited evidence that combination of an NSAID and a muscle relaxant is modestly more effective than either agent alone.61 No studies have demonstrated benefit of muscle relaxants in chronic low back pain.62,63

Approximately 50% of persons treated with muscle relaxants experience an adverse effect, most commonly dizziness and sedation.60 Benzodiazepines, cyclobenzaprine, and tizanidine tend to be more sedating than metaxalone or methocarbamol. However, alertness and cognitive acuity may be impaired by any muscle relaxant. Carisoprodol is metabolized to meprobamate, a highly addictive barbiturate. Because carisoprodol is not more effective than alternative muscle relaxants, it should be avoided. Cyclobenzaprine is chemically in the same class as tricyclic antidepressants and should not be used in patients with significant cardiac arrhythmias.

Anticonvulsants, Antiepileptics, and Membrane Stabilizers

There is limited evidence directly evaluating the efficacy of antiepileptic medications for chronic low back, radicular, or neuropathic pain. However, use of these medications may be reasonable for patients with persistent back or neck pain despite treatment with simple analgesics, NSAIDs, or tricyclic antidepressants.64 Gabapentin has U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved labeling for trigeminal neuralgia, but is widely used to treat neuropathic pain of other sources. Dose-related sedation is a limiting factor with gabapentin. Pregabalin is one of the newer membrane stabilizers used in painful neuropathic and musculoskeletal conditions, including fibromyalgia. Carbamazepine is an older anticonvulsant that has FDA-approved labeling for trigeminal neuralgia and is sometimes used for other types of neuropathic pain. Oxcarbamazepine, topiramate, lamotrigine, tiagabine, and valproate have been reported in case studies to offer relief from neuropathic discomfort. These agents are typically used at their anticonvulsant dosages. Antiepileptic drugs act at several sites that may be relevant to pain, but the precise mechanism of their analgesic effect remains unclear. They may limit neuronal excitation and enhance inhibition. Transmission of painful stimuli through the spinal column and central nervous system is modulated by excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters, as well as actions at sodium and calcium channels. Antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs are also thought to diminish neuropathic pain through interaction with specific neurotransmitters and ion channels.

Acupuncture

As acupuncture has become established in the West, studies investigating its physiologic effects have found several potential explanations for the analgesic effect of the procedure. Because acupuncture stimulates A delta fibers entering the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, potentially inhibiting unmyelinated C-fiber pain impulses, a gate theory mechanism of analgesia has been suggested. Acupuncture needling increases cerebrospinal fluid levels of various neuropeptides, including serotonin, endorphins, and enkephalins, an effect that can be blocked by naloxone.65 An anti-inflammatory effect of acupuncture has been proposed based on elevated adrenocorticotropic hormone levels noted after needling. Functional MRI of the brain has demonstrated that acupuncture activates central antinociceptive pathways while decreasing activity in limbic areas involved in pain processing.66 Evidence that acupuncture meridians and points correspond to intermuscular or intramuscular fascia has led to the hypothesis that needling may stimulate bioelectrical or biochemical signaling along these connective tissue planes.67

Acupuncture has been increasingly accepted as a useful modality in the treatment of back and neck pain. Approximately two thirds of pain specialists and rheumatologists report referrals to practitioners of acupuncture.68,69 A National Institutes of Health consensus conference in 1998 concluded that acupuncture might be useful as an adjunct treatment for low back pain or an acceptable alternative to be included in a comprehensive management program.70 Ten years later, the recently published American College of Physicians and American Pain Society guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain recommends acupuncture be considered as a nonpharmacologic treatment with proven benefits for patients with chronic or subacute, nonspecific low back pain.13 A recent systematic review of the effectiveness of acupuncture for back pain found 23 randomized, controlled trials including more than 6000 patients.71 This analysis concluded that there is moderate evidence that acupuncture is more effective than no treatment and strong evidence of no significant difference between acupuncture and sham acupuncture for short-term pain relief. The authors also concluded that there is strong evidence that acupuncture can be a useful supplement to other forms of conventional treatment for nonspecific low back pain. Another recent systematic review of acupuncture in patients with chronic low back pain included 19 studies with more than 5000 patients and concluded that the most consistent evidence demonstrated that the addition of acupuncture to other therapies was superior in pain relief and functional improvement compared with the same therapies without acupuncture.72 A variant of acupuncture, percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS), has been demonstrated to be significantly more effective than sham-PENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and exercise in treating back pain attributed to degenerative disc disease.73 This technique uses electrical stimulation of acupuncture needles that have been placed in soft tissue or muscular points arrayed to stimulate peripheral sensory nerves in a dermatomal distribution corresponding to the local pathologic process.

A systematic review of acupuncture for neck pain found 10 randomized, controlled trials of variable quality and concluded there was moderate evidence that acupuncture was more effective for pain relief than sham procedures immediately after treatment and at short-term follow-up.3 For chronic neck pain, acupuncture has been shown to be superior to massage.74 In this study, however, no difference was found between “real” and “sham” acupuncture.

A reasonable trial of acupuncture in most patients requires 6 to 10 treatments, perhaps more in older patients. Acupuncture is contraindicated in patients with severe bleeding disorders or systemic infection. Electroacupuncture should be avoided in patients with pacemakers, defibrillators, implanted medication pumps, and implanted neuromodulating devices. In pregnant patients, acupuncture points that may stimulate labor are “forbidden.” Opioid-dependent patients may be less responsive to acupuncture. Serious complications of acupuncture such as organ or vascular puncture are extremely rare. Minor adverse effects, including local bleeding or pain, are seen in about 5% of patients.72

Manipulation

Spinal manipulation is defined as the application of high-velocity, low-amplitude manual thrusts to the spinal joints with movement beyond the passive range of motion.75 Although the use of spinal manipulation for healing was described in the writings of Galen and Hippocrates, the “modern era” of manipulation dates to the late 19th century, when both chiropractic treatment and osteopathy emerged as medical disciplines.76 Chiropractors perform more than 90% of all manipulations in the United States, but other practitioners include osteopathic physicians and physical therapists.77 Almost 90% of visits to chiropractors are for neck or back pain.78

Manipulation techniques vary considerably based on the training of the practitioner. In general, osteopathic manipulation uses a long-lever, lower-velocity technique using a long bone such as the femur to apply force to one or more joints.77 Short-lever, higher-velocity manipulation of a specific joint represents the more commonly performed chiropractic spinal “adjustment.” More recently, medicine-assisted manipulation has been reintroduced, primarily in the chiropractic community. This technique involves spinal manipulation after local anesthesia (epidural or facet) or with deep conscious sedation.79 To date, medicine assisted–manipulation has not been evaluated in a controlled trial.

The precise mechanism of action for any effects attributed to manipulation remains unknown. Current hypotheses focus on either direct effects on the facet joints themselves or secondary neurologic effects of facet and myofascial manipulation. Manipulation may release trapped synovial plica, alter orientation of the joint, relax periarticular hypertonic muscles, disrupt adhesions, or unbuckle abnormal motion segments.75,77 There is some evidence that manipulation may affect afferent nerves in the paraspinal musculature, inhibiting excessive reflex activity and potentially affecting central pain processing.80,81

For patients with acute or subacute low back pain, manipulation has been shown to be superior to sham manipulation but not statistically or clinically superior to general care, analgesics, physical therapy, exercises, or back schools.82 In a randomized clinical trial, patients with acute and subacute back pain treated with osteopathic manipulation required significantly less medication than the standard care group, however.83 In another large, prospective, randomized trial comparing chiropractic manipulation with medical care, including physical therapy, similar outcomes were noted in pain and disability, but patients treated with manipulation had a greater likelihood of perceived improvement.84 For patients with chronic low back pain, a recent systematic review of 11 trials including approximately 1200 patients found moderate evidence that manipulation was superior to usual medical care or placebo for patient-rated improvement.75 Manipulation with strengthening exercises was comparable to prescription NSAIDs for pain relief. For mechanical neck pain, manipulation in addition to exercise was found superior to waiting list controls for pain reduction in a systematic review of 33 trials.85

Mild adverse effects of spinal manipulation occur in 30% to 61% of all patients.86 Most of these effects occur within 4 hours of treatment and resolve the same day. The most common symptoms reported include local discomfort (53%), headache (12%), tiredness (11%), radiating discomfort (10%), and dizziness (5%).87 Serious adverse affects of lumbar manipulation such as disc herniation or cauda equina syndrome are rare, estimated at 1 event per 3.72 million manipulations.88 Risk of serious injury from cervical manipulation, particularly vertebral artery dissection, is well described, but the frequency is unknown. Although likely rare, the consequences of this complication are potentially catastrophic, such that some have suggested avoidance of cervical manipulation in patients with known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.86

Massage

Massage, defined as manipulation of muscle and fascia using one’s hands or a mechanical device, is a widely used adjunctive treatment in patients with neck and back pain. Common variations of massage include Rolfing, Swedish massage, acupuncture massage, myofascial release, and craniosacral therapy. Therapeutic benefits of massage have been attributed to local effects, including increased blood flow and oxygenation of tissues and relaxation of tight muscles.89,90 Other proposed mechanisms include stimulation of serotonin or endorphin release, as well as effects on pain transmission at the spinal segmental level.

Recent systematic reviews of massage therapy have concluded that massage is effective for subacute and chronic low back pain.89,90 Although limited in number and mixed in quality, clinical trials have shown massage is more effective than exercise, acupuncture, and self-care education in improving symptoms and function in patients with nonspecific low back pain.91,92 Several trials have suggested that the addition of massage to exercise improves outcome in patients with low back pain compared with exercise alone.90 These studies also suggest that the experience of the massage therapist influences outcome. The optimal number and frequency of treatments are not known.

Studies of massage for chronic neck pain are less definitive. A recent review of 19 trials of massage for “mechanical” neck pain found 12 were of low quality.93 The remaining studies of massage for neck pain as a stand-alone treatment or as part of a multimodality treatment approach were inconclusive.

Traction

Theoretically, the objective of spinal traction is to distract the vertebrae, potentially reducing protrusion of a bulging or herniated disc. Approximately 1.5 times a patient’s body weight is needed to develop distraction of the vertebral bodies. This is rarely achieved in clinical practice because patient tolerance is poor. No specific effect of traction over standard physiotherapeutic interventions was observed in adults with chronic neck pain. Conceptually, traction may be useful as an adjunct to active exercise therapy to assist in releasing muscle spasm and facilitating active therapy, but evidence for benefit is lacking.94 The current literature does not support or refute the effectiveness of continuous or intermittent traction for pain reduction, improved function, or global perceived effect compared with placebo traction, tablet or heat, or other conservative treatments in patients with chronic neck disorders.95 Only limited evidence is available to warrant the routine use of nonsurgical spinal decompression, particularly when many other well-investigated, less expensive alternatives are available.96

Summary: An Aggressive, Evidence-Informed Approach to Nonsurgical Management of Back and Neck Pain

Acute Pain (<4 Weeks)

If a focused history and physical examination, carefully assessing risk factors for underlying serious causes (“red flags”) and psychosocial risk factors for prolonged recovery and disability (“yellow flags”) is unrevealing, initial treatment should include a simple, age-appropriate analgesic or NSAID for symptom control and emphasize the importance of maintaining physical activities as tolerated (Box 188-2). For patients with significant muscle spasm, the addition of a muscle relaxant for up to 1 week is appropriate. Perhaps the most important feature of early treatment is education of the patient about the favorable natural history of low back or neck pain, the benefits of early appropriate physical activity, and the importance of general health measures in promoting spine wellness, including smoking cessation, aerobic exercise, and weight management.

Recommendation: Provide patients with evidence-based information on low back pain with regard to expected course, advise patients to remain active, and provide information about effective self-care options.

Recommendation: Consider the use of medications with proven benefits in conjunction with back care information and self-care. Assess severity of pain and functional deficits, potential benefits, risks, and relative lack of long-term efficacy and safety data before initiating therapy. For most patients, first-line medication options are acetaminophen or NSAIDs.

Recommendation: For patients who do not improve with self-care options, clinicians should consider addition of nonpharmacologic therapy with proven benefits:

From Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med 147:478–491, 2007.

Subacute Pain (4 to 12 Weeks)

Patients with nonspecific back or neck pain who have persistent significant symptoms and impaired function after 4 weeks of appropriate medical therapy must be reevaluated. Repeating a careful history and physical examination is required, including another search for previously unrecognized serious causes (infection, malignancy, or fracture) of pain as well as psychosocial barriers to recovery. Some patients may be identified whose clinical picture has now evolved from a purely axial pain syndrome to a radicular pattern, requiring a different approach. If indicated, and particularly in older patients, appropriate laboratory and imaging studies may be required. If this evaluation fails to identify new findings, more aggressive medical treatment is indicated, including referral for formal physical therapy, emphasizing an active exercise approach with education. Additional nonpharmacologic modalities, including acupuncture, manipulation, and massage therapy may be used to provide additional analgesic benefit and facilitate rehabilitation. Patients manifesting “yellow flags” may be referred for more formal psychosocial assessment and treatment. In the case of work-related back pain, vocational rehabilitation and active job-specific rehabilitation (“work hardening”) may be indicated.

Carragee E.J., Alamin T.F., Miller J.L., et al. Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain. Spine J. 2005;5:24-35.

Chang V., Gonzalez P., Akuthota V. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with adjunctive analgesics. Spine J. 2008;8:21-27.

Chou R., Huffman L.H. Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:505-514.

Chou R., Qaseem A., Snow V., et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478-491.

Malanga G., Wolff E. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxants, and simple analgesics. Spine J. 2008;8:173-184.

May S., Donelson R. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with the McKenzie method. Spine J. 2008;8:134-141.

Schofferman J., Mazanec D. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with opioid analgesics. Spine J. 2008;8:185-194.

1. Deyo R.A., Mizra S.K., Martin B.I. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from the U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2724-2727.

2. Hart L.G., Deyo R.A., Cherkin D.C. Physician office visits for low back pain: frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns from a U.S. national survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:11-19.

3. Trinh K., Graham N., Gross A., et al. Acupuncture for neck disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:236-243.

4. Andersson G.B. Epidemiological features of chronic low back pain. Lancet. 1999;354:581-585.

5. Luo X., Pietrobon R., Sun S.X., et al. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:79-86.

6. Dagenais S., Caro J., Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J. 2008;8:8-20.

7. Pengel L.H., Herbert R.D., Maher C.G., et al. Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis. BMJ. 2003;327:323.

8. Grotle M., Brox J.I., Veierod M.B., et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: patients consulting primary care for the first time. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:976-982.

9. Von Korff M., Saunders K. The course of back pain in primary care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:2833-2837.

10. Burton A.K., Tilloston K.M., Main C.J., et al. Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and sub acute low back trouble. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;20:722-728.

11. Carragee E.J., Alamin T.F., Miller J.L., et al. Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain. Spine J. 2005;5:24-35.

12. Pincus T., Burton A.K., Vogel S., et al. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:E109-E120.

13. Chou R., Qaseem A., Snow V., et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478-491.

14. Jarvik J.G., Deyo R.A. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:586-597.

15. Kendrick D., Fielding K., Bentley E., et al. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322:400-405.

16. Hammouri Q.M., Haims A.H., Simpson A.K., et al. The utility of dynamic flexion-extension radiographs in the initial evaluation of the degenerative lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:2361-2364.

17. Jensen M.C., Brant-Zawadzki M.N., Obuchowski N., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69-73.

18. Siemionow K., Steinmetz M., Bell G., et al. Identifying serious causes of back pain: cancer, infection, fracture. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75:557-566.

19. Bigos S.J., Holland J., Holland C., et al. High-quality controlled trials on preventing episodes of back problems: systematic literature review in working-age adults. Spine J. 2009;9:147-168.

20. Fanuele J.C., Abdu W.A., Hanscom B., et al. Association between obesity and functional status in patients with spine disease. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:306-312.

21. Leboeuf-Yde C. Smoking and low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:1463-1470.

22. Hayden J.A., van Tulder M.W., Malmivaara A.V., et al. Meta-analysis: exercise therapy for nonspecific low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:756-775.

23. Malmimaara A., Hakkinen U., Aro T., et al. The treatment of acute low back pain: bedrest, exercise, or ordinary activity? N Engl J Med. 1995;332:351-355.

24. Walker M.J., Boyles R.E., Young B.A., et al. The effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise for mechanical neck pain: a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:2371-2378.

25. Fritz J.M., Delitto A., Erhard R.E. Comparison of classification-based physical therapy with therapy based on clinical practice guidelines for patients with acute low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:1363-1372.

26. Long A., Donelson R., Fung T. Does it matter which exercise: a randomized, controlled trial for low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:2593-2602.

27. Sculco A.D., Paup D.C., Ferhall B., et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on low back pain patients in treatment. Spine J. 2001;1:95-101.

28. Dusuneceli Y., Ozturk C., Atamaz F., et al. Efficacy of neck stabilization exercises for neck pain: a randomized controlled study. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:626-631.

29. Standaert C.J., Weinstein S.M., Rumpeltes J. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with lumbar stabilization exercises. Spine J. 2008;8:114-120.

30. Mayer J., Mooney V., Dagenais S. Evidence informed management of chronic low back pain with lumbar extension strengthening exercises. Spine J. 2008;8:96-113.

31. Sorosky S., Stilp S., Akuthota V. Yoga and Pilates in the management of low back pain. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1:39-47.

32. LaTouche R., Escalante K., Linares M.T. Treating nonspecific chronic low back pain through the Pilates method. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2008;12:364-370.

33. May S., Donelson R. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with the McKenzie method. Spine J. 2008;8:134-141.

34. Peterson T., Kryger P., Ekdahl C., et al. The effect of McKenzie therapy as compared with that of intensive strengthening training for the treatment of patients with acute or sub acute chronic back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:1702-1709.

35. Miller E.R., Schenk R.J., Karnes J.L., et al. A comparison of the McKenzie approach to a specific spine stabilization program for chronic low back pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2005;13:103-112.

36. Waller B., Lambeck J., Daly D. Therapeutic aquatic exercise in the treatment of low back pain: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:3-14.

37. Chou R., Huffman L.H. Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:505-514.

38. van Tulder M.W., Scholten RJPM, Koes B.W., et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:2501-2513.

39. Pincus T., Koch G.C., Sokka T., et al. A randomized double-blind placebo crossover clinical trial of diclofenac plus misoprostol versus acetaminophen in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1587-1598.

40. Roelofs P., Deyo R.A., Koes B.W., et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: an updated Cochrane Review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:1766-1774.

41. van Tulder M.W., Koes B.W., Bouter L.M. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review of the most common interventions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:2128-2156.

42. Antman E.M., Bennet J.S., Daugherty A., et al. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;115:1634-1642.

43. American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacologic management of persistent pain in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1331-1346.

44. Friedman B.W., Holden L., Esses D., et al. Parenteral corticosteroids for emergency department patients with non-radicular low back pain. J Emerg Med. 2006;31:365-370.

45. Atkinson J.H., Slater M.A., Wahlgren D.R., et al. Effects of noradrenergic and serotonergic antidepressants on chronic low back pain intensity. Pain. 1999;83:137-145.

46. Portenoy R.K., Foley K.M. Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non-malignant pain: report of 38 cases. Pain. 1986;25:171-186.

47. Mahowald M.L., Singh J.A., Majeski P. Opioid use by patients in an orthopedics spine clinic. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:312-321.

48. Schofferman J., Mazanec D. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with opioid analgesics. Spine J. 2008;8:185-194.

49. Smith H.S. Opioid metabolism. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:613-624.

50. Fishman S.M., Wilsey B., Mahajan G., et al. Methadone reincarnated: novel clinical applications with related concerns. Pain Med. 2002;3:339-348.

51. Ripple M.G., Pestaner J.P., Levine B.S., et al. Lethal combination of tramadol and multiple drugs affecting serotonin. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2000;21:370-374.

52. Szeto H.H., Inturrisi C.E., Houde R., et al. Accumulation of normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine in patients with renal failure of cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:738-741.

53. Martell B.A., O’Connor P.G., Kerns R.D., et al. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:116-127.

54. Argoff C.E., Silverman D.I. A comparison of long- and short-acting opioids for treatment of chronic noncancer pain: tailoring therapy to meet patient needs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:602-612.

55. Schofferman J. Long-term opioid analgesic therapy for severe refractory lumbar spine pain. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:136-140.

56. Allan L., Richarz U., Simpson K., et al. Transdermal fentanyl versus sustained relief oral morphine in strong opioid-naïve patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2484-2490.

57. Fishbain D.A., Cutler R.B., Rosomoff H.L., et al. Are opioid-dependent/tolerant patients impaired in driving-related skills? A structured, evidenced-based review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:559-577.

58. Daniell H.W. DHEAS deficiency during consumption of sustained-action prescribed opioids: evidence for opioid-induced inhibition of adrenal androgen production. J Pain. 2006;7:901-907.

59. Passik S.D. Issues in long-term opioid therapy: unmet needs, risks, and solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:593-601.

60. Malanga G., Wolff E. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxants, and simple analgesics. Spine J. 2008;8:173-184.

61. Borenstein D.G. Cyclobenzaprine and naproxen versus naproxen alone in the treatment of acute low back pain and muscle spasm. Clin Ther. 1990;12:125-131.

62. Browning R., Jackson J.L., O’Malley P.G. Cyclobenzaprine and back pain: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1613-1620.

63. van Tulder M.W., Touray T., Furlan A.D., et al. Muscle relaxants for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 28, 2003. 1978-1992

64. Chang V., Gonzalez P., Akuthota V. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with adjunctive analgesics. Spine J. 2008;8:21-27.

65. Sierpina V.S., Frenkel M.A. Acupuncture: a clinical review. South Med J. 2005;98:330-337.

66. Wu M.T., Hsieh J.C., Xiong J., et al. Central nervous pathways for acupuncture stimulation: localization of processing with functional MR imaging of the brain—preliminary experience. Radiology. 1999;212:133-141.

67. Langevin H.M., Yandow J.A. Relationship of acupuncture points and meridians to connective tissue planes. Anat Rec. 2002;269:257-265.

68. Berman B.M., Bausell R.B. The use of non-pharmacologic therapies by pain specialists. Pain. 2000;85:313-316.

69. Berman B.M., Bausell R.B., Lee W.L. Use and referral patterns for 22 complementary and alternative medical therapies by members of the American College of Rheumatology: results of a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:766-770.

70. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Acupuncture: Acupuncture. JAMA. 1998;280:1518-1524.

71. Yuan J., Purepong N., Kerr D.P., et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture for low back pain: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:E887-E900.

72. Ammendolia C., Furlan A.D.D., Imamura M., et al. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with needle acupuncture. Spine J. 2008;8:160-172.

73. Ghoname E.A., Craig W.F., White P.F., et al. Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for low back pain: a randomized crossover study. JAMA. 1999;281:818-823.

74. Irnich D.D., Behrens N., Molzen H., et al. Randomized trial of acupuncture compared with conventional massage and “sham” laser acupuncture for treatment of chronic neck pain. BMJ. 2001;322:1-6.

75. Bronfort G., Haas M., Evans R., et al. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with spinal manipulation and mobilization. Spine J. 2008;8:213-225.

76. Meeker W.C., Haldeman S. Chiropractic: a profession at the crossroads of mainstream and alternative medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:216-227.

77. Shekelle P.G., Adams A.H., Chassin M.R., et al. Spinal manipulation for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:590-598.

78. Hurwitz E.L., Coulter I.D., Adams A.H., et al. Use of chiropractic services from 1985 through 1991 in the United States and Canada. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:771-776.

79. Dagenais S., Mayer J., Wooley J.R., et al. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with medicine-assisted manipulation. Spine J. 2008;8:142-149.

80. Bolton P.S. Reflex effects of vertebral subluxations: the peripheral nervous system. An update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23:101-103.

81. Pickar J.G. Neurophysiological effect of spinal manipulation. Spine J. 2002;2:357-371.

82. Assendelft W.J.J., Morton S.C., Yu E.I., et al. Spinal manipulation for low back pain: a meta-analysis relative to other therapies. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:871-881.

83. Andersson G.B.J., Lucente T., Davis A.M., et al. A comparison of osteopathic spinal manipulation with standard care for patients with low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1426-1431.

84. Hurwitz E.L., Morgenstern H., Kominski G.F., et al. A randomized trial of chiropractic and medical care for patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:611-621.

85. Gross A.R., Hoving J.L., Haines T.A., et al. A Cochrane review of manipulation and mobilization for mechanical neck disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:1541-1548.

86. Ernst E. Adverse effects of spinal manipulation: a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2007;100:330-338.

87. Senstad O., Leboeuf-Yde C., Borchgrevink C. Frequency and characteristics of side effects of spinal manipulation therapy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:435-440.

88. Oliphant D. Safety of spinal manipulation in the treatment of lumbar disc herniations: a systematic review and risk assessment. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27:197-210.

89. Furlan A.D., Brosseau L., Imamura M., et al. Massage for low back pain: a systematic review with the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 27, 2002. 1896-1910

90. Imamura M., Furlan A.D., Drhden T., et al. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with massage. Spine J. 2008;8:121-133.

91. Cherkin D.C., Eisenberg D., Sherman K., et al. Randomized trial comparing traditional Chinese medical acupuncture, therapeutic massage, and self-care education for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1081-1088.

92. Preyde M. Effectiveness of massage therapy for sub acute low-back pain: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2000;162:1815-1820.

93. Ezzo J., Haraldsson G.B., Gross A.R., et al. Massage for mechanical neck disorders: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:353-362.

94. Borman P., Keskin D., Ekici B.D. The efficacy of intermittent cervical traction in patients with chronic neck pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(27):1249-1253.

95. Graham N., Gross A., Goldsmith C.H., et al. Mechanical traction for neck pain with or without radiculopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16(3):CD006408.

96. Daniel D.M. Non-surgical spinal decompression therapy: does the scientific literature support efficacy claims made in advertising media? Chiropr Osteopat. 2007;15:7.