32

Medical disorders in pregnancy

Introduction

Medical disorders are relatively common in pregnancy and often have no implications for the mother or her baby. However, the alteration in maternal physiology, which occurs during pregnancy may affect the medical condition, or the medical condition itself may affect the pregnancy and the baby. Treatment options for the mother may be limited by concerns for fetal welfare and there is therefore the potential for difficult clinical decision-making.

The following conditions will be considered, but see also hypertension (p. 293) and infection in pregnancy (p. 273):

![]() diabetes mellitus

diabetes mellitus

![]() venous thromboembolic disease

venous thromboembolic disease

![]() cardiac disease

cardiac disease

![]() connective tissue disease

connective tissue disease

![]() epilepsy

epilepsy

![]() hepatic disorders

hepatic disorders

![]() renal disorders

renal disorders

![]() respiratory disorders

respiratory disorders

![]() thrombocytopenia

thrombocytopenia

![]() thyroid disorders.

thyroid disorders.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus may be diagnosed before pregnancy (pre-existing) or may be discovered for the first time during pregnancy (gestational). Discovery during pregnancy is rare for type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes but not uncommon for type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. In addition to these, a transient self-limiting state of hyperglycaemia may occur in pregnancy as a result of maternal endocrine changes.

Glucose homeostasis is maintained by the balance between insulin, which reduces glucose levels by increasing cellular uptake, and other hormones such as glucagon and cortisol, which increase glucose production. In pregnancy, the placenta produces additional cortisol as well as other insulin antagonists, such as human placental lactogen, progesterone and human chorionic gonadotrophin, all of which tend to increase the maternal glucose level. If the pancreatic β islet cells are unable to produce sufficient insulin to balance this increase, or if there is maternal insulin resistance, the mother may develop a state of hyperglycaemia referred to as ‘gestational diabetes’.

Women with pre-existing diabetes mellitus may have high glucose levels in the first trimester at the time of organogenesis, and there is a consequent increase in the rate of congenital abnormalities. The abnormalities are principally cardiac defects, neural tube defects and renal anomalies and are more likely to occur when diabetic control has been poor. Although the mechanism of this teratogenesis is unclear, there is evidence that improved pre-pregnancy and early pregnancy blood glucose control reduces the risk of congenital abnormality.

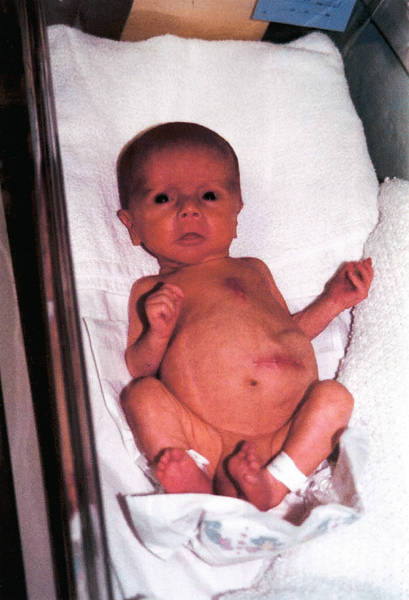

Fetal glucose levels closely reflect those of the mother, with glucose crossing the placenta through facilitated diffusion. Maternal insulin does not cross the placenta and the fetus produces its own insulin from around 10 weeks’ gestation. This insulin is recognized to have a significant role in promoting fetal growth. As maternal levels of glucose are higher in mothers with diabetes, fetal levels are also increased and, in turn, there is increased fetal insulin production. This fetal hyperinsulinaemia often results in macrosomia (large babies) and organomegaly as well as increased erythropoiesis and neonatal polycythaemia.

In addition to the risk of congenital abnormality, there is also a risk of unexplained intrauterine fetal death, possibly because fetal hyperinsulinaemia leads to chronic hypoxia and acidaemia. A macrosomic fetus may be more at risk of these complications because of its increased oxygen demands.

Because babies of women with diabetes are often macrosomic, labour and delivery may be complicated by dystocia and in particular, shoulder dystocia. Neonates may have hypoglycaemia, hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia and polycythaemia. There is also an increased incidence of hyaline membrane disease.

Effects of pregnancy on diabetes

Insulin requirements may be static or decrease during the first trimester. They typically increase during the second and third trimesters and may reduce slightly towards term. Pregnancy may exacerbate diabetic retinopathy, and the fundi should be assessed for signs of proliferative retinopathy, with laser treatment advised as necessary.

Effects of diabetes on pregnancy

The incidence of pre-eclampsia is increased. There is also an increased incidence of maternal infection, particularly of the urinary tract. Polyhydramnios, which probably results from fetal polyuria, may result in unstable lie, malpresentation and pre-term labour.

Screening for gestational diabetes

This is a controversial subject. National (UK) guidelines recommend offering a 75 g glucose tolerance test (GTT) at 24–28 weeks to women with risk factors, including a family history of diabetes; a raised BMI (> 30); a previous macrosomic baby (> 4.5 kg); or those with previous gestational diabetes (GDM). For those with previous GDM, early self-monitoring or a GTT should be offered at 16–18 weeks and, if normal, repeated at 28 weeks.

The normal fasting plasma glucose is < 5.5 mmol/L. For an oral GTT, patients should fast overnight. Venous blood is taken for fasting blood glucose and a 75 g glucose drink is given. Further venous blood samples are taken after 1 h and 2 h. The International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups’ diagnostic criteria are:

![]() GDM

GDM

![]() fasting glucose ≥ 5.1 mmol/L and/or 2-h level > 8.5 mmol/L

fasting glucose ≥ 5.1 mmol/L and/or 2-h level > 8.5 mmol/L

![]() Overt diabetes

Overt diabetes

![]() fasting glucose > 7.0 mmol/L or

fasting glucose > 7.0 mmol/L or

![]() HbA1c > 6.5% or

HbA1c > 6.5% or

![]() Random plasma glucose > 11.1 mmol/L.

Random plasma glucose > 11.1 mmol/L.

Management of gestational diabetes

Treatment with dietary advice and adjustment should be the first step, and metformin and then insulin therapy instituted if the target levels are not achieved. Insulin treatment should aim to keep the preprandial glucose < 5.5 mmol/L and postprandial < 7.5/8 mmol/L.

Women with GDM have an increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus in the subsequent 25 years. Recurrence of GDM in subsequent pregnancies is up to 75% (especially if treatment with insulin was required).

Antenatal management of established diabetes

At pre-pregnancy counselling, advice should be given about good diabetic control, diet, smoking and high-dose (5 mg) folate supplements. Pregnancy management should be in a combined obstetric/diabetic clinic, with frequent visits planned as required. Blood glucose should be measured several times a day at home, aiming for tight control (e.g. with preprandial levels 3.5–5.9 mmol/L and 1-h postprandial levels of < 7.8 mmol/L). Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) should be checked monthly when planning a pregnancy and in early pregnancy, aiming for levels towards 6.0%.

Insulin is commonly given as a short-acting analogue three times a day (with meals), with an intermediate- or long-acting insulin once or twice a day as background. Ketoacidosis should be avoided, as it is associated with an increased risk of perinatal mortality.

Maternal kidney function and optic fundi should be examined in early pregnancy, and a detailed anomaly scan offered at 18–22 weeks. The maternal abdomen should be examined for polyhydramnios, macrosomia or fetal growth restriction (measurement of symphysis–fundal height), and serial ultrasound fetal biometry is recommended.

Delivery at 38 weeks is recommended but there is no indication for elective caesarean section on the basis of diabetes alone. If pre-term labour occurs, steroids may be given as for the non-diabetic patient, but will lead to marked deterioration in diabetic control, unless insulin doses are increased appropriately or a sliding scale employed.

Delivery

Concern regarding fetal macrosomia and the potential for shoulder dystocia in particular, may necessitate a planned caesarean section.

There are numerous different regimens of intravenous dextrose and insulin, but the aim of them all is to maintain tight intrapartum control, whether during labour or for caesarean section. In the immediate postpartum period, insulin requirements rapidly return to pre-pregnancy levels and the previous subcutaneous regimen can be re-established. For women with GDM, insulin should be discontinued following delivery.

Venous thromboembolic disease

Antenatal

In pregnancy, the balance of the coagulation system is altered towards thrombus formation. There are increased levels of fibrinogen, prothrombin and other clotting factors, together with reduced levels of endogenous anticoagulants. This tendency to clot formation is only in part offset by an increase in fibrinolysis. In addition to the clotting system changes, the gravid uterus causes a degree of mechanical obstruction to the venous system and leads to peripheral venous stasis in the lower limbs.

Venous thromboembolic disease appears to be very rare in Africa and the Far East but is a common direct cause of maternal mortality in the UK. The reason for such wide racial differences may be that the factor V Leiden mutation and prothrombin gene variants are rare in African and Asian populations. In the UK, over 50% of maternal deaths from thromboembolism occur antenatally.

Over 80% of deep venous thromboses (DVTs) in pregnancy are left-sided, in contrast to only 55% in the non-pregnant woman. This difference may reflect compression of the left common iliac vein by the right common iliac artery and the ovarian artery, which cross the vein on the left side only. The gravid uterus lies over the right common iliac artery. Furthermore, over 70% of DVTs in pregnancy are iliofemoral rather than femoral popliteal compared with the non-pregnant rate of around 9%, and are therefore more likely, than lower calf vein thromboses, to give rise to pulmonary embolism.

Thromboembolism may be asymptomatic but usually presents with the traditional symptoms and signs, such as calf tenderness, breathlessness and chest pain. It may also present with lower abdominal or groin pain. It is essential to make a definitive diagnosis, not just for management of the current pregnancy but because there are major implications with regard to the need for thromboprophylaxis in subsequent pregnancies.

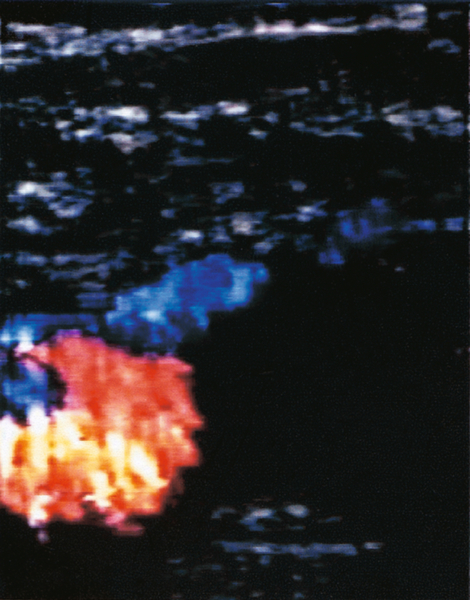

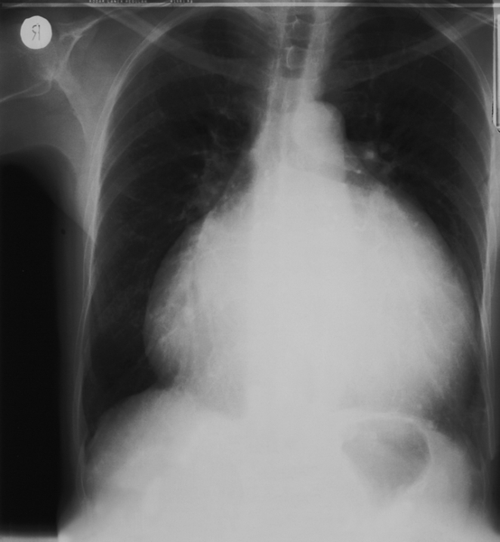

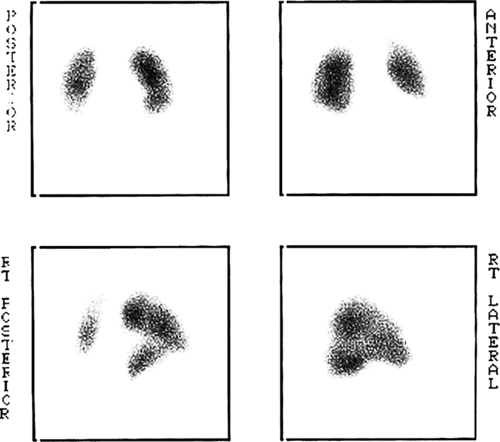

Haematological testing for D-dimers is not helpful in pregnancy. Radiological investigations are required if there is clinical suspicion. Duplex Doppler ultrasound is particularly useful for identifying femoral vein thromboses, although iliac veins are less easily seen (Fig. 32.1). It is safe and should be the first-line investigation. X-ray venography is more specific, but has the disadvantage of radiation exposure. Venography or magnetic resonance venography (MRV) is appropriate if Doppler studies give equivocal results, or negative results, despite strong clinical suspicion. Pregnancy is not a contraindication to carrying out a chest X-ray and/or a ventilation-perfusion (![]() ) scan – any radiation risks are outweighed by the benefits of accurate diagnosis (Fig. 32.2). A normal scan virtually excludes the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. A computerized tomography pulmonary arteriogram (CTPA) may also be appropriate, especially if the chest X-ray is abnormal or an alternative diagnosis is suspected. CTPA, despite involving less radiation to the fetus than (

) scan – any radiation risks are outweighed by the benefits of accurate diagnosis (Fig. 32.2). A normal scan virtually excludes the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. A computerized tomography pulmonary arteriogram (CTPA) may also be appropriate, especially if the chest X-ray is abnormal or an alternative diagnosis is suspected. CTPA, despite involving less radiation to the fetus than (![]() ) scanning is associated with significant radiation to the maternal breasts.

) scanning is associated with significant radiation to the maternal breasts.

Note the lack of perfusion in the right lower lobe. The ventilation scan was normal.

Treatment of DVT or pulmonary embolism in pregnancy is with subcutaneous (s.c.) low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). Intravenous (i.v.) unfractionated heparin is appropriate in cases of massive pulmonary embolus. LMWH therapy is interrupted for delivery to allow for regional analgesia and anaesthesia and to minimize the risk of haemorrhage. After delivery, the woman may choose to continue with s.c. LMWH or commence warfarin, continuing anticoagulation for 6–12 weeks as decided by timing of onset and clinical severity of the thrombosis.

The management of those with a previous history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is dependent on the circumstances of the previous VTE. Women who have experienced a single provoked episode of VTE should be screened for thrombophilia (Box 32.1). If the screen is negative, and the event occurred outside pregnancy and was not severe, antenatal thromboprophylaxis may not be required. Postnatal thromboprophylaxis with LMWH should be recommended for 6 weeks. If the screen is positive, or there are other risk factors or a positive family history, antenatal and postnatal prophylaxis with LMWH should be offered. Women with previous unprovoked, multiple, oestrogen-related (pill or pregnancy) or thrombophilia-related VTE should also be offered antenatal and postnatal prophylaxis with LMWH.

Antenatal and postnatal risk assessment

The risks of thromboembolism should be assessed in all women at booking, at the time of any antenatal hospital admission and after delivery (see Box 32.2), and those at risk (previous thrombosis, thrombophilia, emergency caesarean section or any two (postnatal or admitted) or three (antenatal) of the other risk factors) offered thromboprophylaxis with LMWH (e.g. enoxaparin 40 mg once daily).

Cardiac disease

Heart disease complicates less than 1% of all pregnancies but accounts for around 20% of maternal deaths in the UK. Rheumatic heart disease remains a significant problem in the developing world and it is also encountered with increasing frequency in western countries, as a result of migration. There are increasing numbers of fertile women who have had surgery as children for congenital heart disease. Maternal mortality is highest in conditions where pulmonary blood flow cannot be increased to compensate for the increased demand during pregnancy – particularly Eisenmenger syndrome, where maternal mortality rates reach 40–50%.

Unfortunately, many symptoms and signs similar to those of heart disease occur commonly in normal pregnancy, making a clinical diagnosis difficult. Breathlessness and syncopal episodes are present in 90% of normal pregnancies, atrial ectopic beats are common, and up to 96% of normal women may have an audible ejection systolic murmur. Further investigation should be considered if the murmur is loud (> 2/6), diastolic, if a precordial thrill is present or if there are any other suspicious features, especially in migrant women.

If problems are discovered, a cardiologist should be involved during the antenatal period. If there is no haemodynamic compromise (e.g. congenital mitral valve prolapse), the prognosis is good and there is often no requirement for cardiac follow-up. If there are potential haemodynamic problems, very close follow-up by a multidisciplinary team is mandatory and a careful plan should be made for delivery. Serious consideration of pregnancy termination is advisable in women with Eisenmenger syndrome, any cause of pulmonary hypertension, or pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. With atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation is required to prevent atrial clot forming and subsequent embolic problems. If the maternal PO2 is decreased, the fetus is at risk from hypoxia and fetal growth restriction, and should be monitored closely.

Severe cardiac disease can cause problems at delivery, particularly in those with prosthetic valves, aortic stenosis, mitral stenosis, left ventricular dysfunction, or pulmonary hypertension (Box 32.3).

Myocardial infarction is rare in pregnancy but is the commonest cardiac cause of maternal mortality. Peripartum cardiomyopathy is also rare (< 1:5000), but carries a 5% mortality and is associated with hypertension in pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, high multiparity and increased maternal age. It presents with sudden onset of heart failure and on chest radiology or echocardiography, there is usually a grossly dilated heart (Fig. 32.3).

Connective tissue disease

These diseases are not uncommon and, as they often affect women during their childbearing years, they are not infrequently found in association with pregnancy. See also the antiphospholipid syndrome page 87.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

There is an increased chance of an exacerbation of SLE (flare-up) occurring in pregnancy and during the postnatal period. Women should be discouraged from becoming pregnant when their disease is active, to minimize problems. Active SLE nephritis during pregnancy is associated with significant maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity, and in particular with a risk of pre-eclampsia.

SLE nephritis is associated with increased fetal loss rates from spontaneous miscarriages and preterm delivery. This is particularly so in those with antiphospholipid antibodies. There is an increased incidence of pre-eclampsia and this may be difficult to differentiate from a disease flare, as both are associated with hypertension and proteinuria. There is no increase in the rate of fetal abnormalities, although there is a risk of fetal congenital heart block associated with the presence of anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies (Fig. 32.4). Neonatal lupus may rarely occur and is characterized by haemolytic anaemia, leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, discoid skin lesions, pericarditis and congenital heart block.

If lupus anticoagulant or anticardiolipin antibodies (antiphospholipid antibodies) are present, low-dose aspirin should be given, and in women with a previous history of thromboembolic disease or adverse pregnancy outcome, low-molecular-weight heparin is indicated. Careful monitoring of renal function is appropriate. Flare-ups should be managed where possible, with oral prednisolone and there should be regular ultrasound fetal biometry owing to the increased risk of fetal growth restriction.

Epilepsy

A first seizure in the second half of pregnancy should be assumed to be eclampsia until proven otherwise. Around a third of pregnant women with epilepsy have an increase in seizure frequency independent of the effects of medication. For women with epilepsy on treatment, the fall in antiepileptic drug (AED) levels due to dilution, reduced absorption, reduced compliance and increased drug metabolism is partially compensated for by reduced protein binding (and therefore an increase in the level of free drug) for phenytoin, but for most AEDs the free drug levels fall in pregnancy. This is particularly the case for lamotrigine. There is an increased incidence of fetal anomalies in association with AEDs (6% vs 3% in the general population) (Fig. 32.5). Single-drug regimens are less teratogenic than multidrug therapy (Table 32.1) and sodium valproate carries the highest risk of teratogenesis.

Table 32.1

Management of epilepsy in pregnancy

| Pre-pregnancy counselling | Monotherapy with AED ideal. Folate supplementation (5 mg/day) should be continued until at least 12 weeks |

| Antiepileptic drug dosage | AED doses adjusted on clinical grounds. There are fetal risks from AEDs as well as from not taking the drugs (from increased fit frequency) Increased doses and checking plasma levels is recommended for lamotrigine therapy |

| Detailed ultrasound scan at 18–22 weeks | Neural tube, cardiac and craniofacial abnormalities, as well as diaphragmatic herniae, are more common |

| Vitamin K for women on enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants | Oral vitamin K should be given daily from 36 weeks in women receiving enzyme-inducing AEDs to reduce the risk of haemorrhagic disease of the newborn. The baby should be given intramuscular vitamin K stat at birth |

| Seizures | Most seizures in pregnancy will be self-limiting; if prolonged, however, rectal or intravenous diazepam or intravenous lorazepam, with or without ventilation may be required |

| Postnatal | The mother may breastfeed safely (drugs pass into the milk but neonatal levels are low for most AEDs). Advice should be given about safe and suitable settings for feeding, bathing, etc. Carbamazepine, phenytoin, primidone and phenobarbitone induce liver enzymes, reducing the effectiveness of the standard-dose combined oral contraceptives, and a higher-dose oestrogen preparation or alternative form of contraception is therefore required |

Hepatic disorders

There are a large number of potential causes of liver dysfunction in pregnancy (Tables 32.2 and 32.3). A history of a prodromal illness, overseas travel or high-risk group for blood-borne illness may suggest viral hepatitis. Itch is suggestive of cholestasis. Abdominal pain is associated with gallstones, HELLP syndrome (p. 299) or acute fatty liver. Urea and electrolytes (U&Es), urate, liver function tests (LFTs), blood glucose, platelets and coagulation screen should be performed and blood sent for hepatitis serology. Abdominal ultrasound of the liver and gall bladder may show obstruction or gall stones. It is normal for the alkaline phosphatase level to increase in pregnancy (1.5–2 times normal).

Table 32.2

Liver disorders specific to pregnancy

| Hyperemesis gravidarum | This may occasionally be associated with abnormal LFTs |

| Obstetric cholestasis | Usually presents after 30 weeks’ gestation possibly due to a genetic predisposition to the cholestatic effect of oestrogens. Pruritus affects the limbs and trunk and it is often severe. There may be a positive family history in up to 35% of cases. Serum total bile acid concentration is increased early in the disease and is the optimum marker for the condition. Transaminases may be increased (< 3-fold). Bilirubin is usually < 100 μmol/L, and there may be pale stools and dark urine. There are no serious long-term maternal risks but there is a risk of pre-term labour, fetal distress and intrauterine fetal death. Delivery at 37–38 weeks is appropriate if bile acids > 40 μmol/L in an effort to prevent fetal death |

| HELLP syndrome | See page 299 |

| Acute fatty liver of pregnancy | This is very rare, is associated with increased maternal and fetal mortality, and may progress rapidly to hepatic failure. It usually presents with vomiting in the third trimester associated with malaise and abdominal pain, jaundice, thirst and polyuria and may cause hepatic encephalopathy. LFTs are elevated, urate is very high and there is often profound hypoglycaemia. There may be hypertension and proteinuria. Coagulopathy, hypoglycaemia and fluid imbalance should be corrected and the fetus delivered. Following delivery, there is a risk of postpartum haemorrhage and liver dysfunction may be prolonged. Hepatic encephalopathy may develop and liver transplant is occasionally necessary. If the patient recovers, there is no long-term liver impairment |

Table 32.3

Liver disorders coincidental to pregnancy

| Viral hepatitis | Serology should be performed for hepatitis A, B and C as well as for cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and toxoplasmosis (see p. 275) |

| Gall stones | Asymptomatic gallstones do not require treatment. Cholecystitis should be managed conservatively if possible |

| Cirrhosis | In severe cirrhosis, there is usually amenorrhoea. If pregnancy occurs, and the disease is well compensated, there is usually no long-term effect on hepatic function. The main risk is bleeding from oesophageal varices |

| Chronic active hepatitis | Pregnancy does not usually have any long-term effect on liver function. Immunosuppressant therapy with prednisolone and azathioprine should be continued in those with autoimmune disease |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | This is variable in severity. The prognosis for mother and fetus is good in mild disease. It may present during pregnancy for the first time in a similar way to obstetric cholestasis |

Renal disorders

In pregnancy, there is a physiological increase in the size of both kidneys as well as dilatation of the ureter and renal pelvis. This dilatation is greater on the right than on the left because of dextrorotation of the uterus. There is also an increase in creatinine clearance owing to the increased glomerular filtration rate (maximal in the second trimester). In pregnancy, the normal serum urea is < 4.5 mmol/L and creatinine < 75 μmol/L.

Infection

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) occur in 3–7% of pregnancies and, if untreated, may lead to septicaemia and pre-term labour. Asymptomatic bacteriuria should be treated, since there is a 30–40% risk of developing a symptomatic UTI. Pyelonephritis should be treated aggressively.

Obstruction

Acute hydronephrosis is characterized by loin pain, ureteric colic, sterile urine and a renal ultrasound scan showing dilatation of the renal tract greater than normal for pregnancy (Fig. 32.6). If the symptoms are not settling and the ultrasound scan does not demonstrate the cause of the obstruction, a limited intravenous urogram or MRI should be considered. Treatment is with ureteric stenting or nephrostomy. There may be no obvious cause of obstruction and complete resolution may occur following delivery. Renal tract calculi are associated with an increased incidence of UTIs but otherwise do not usually affect pregnancy (unless obstruction is severe).

Fig. 32.6Ultrasound of left kidney with ureteric obstruction and calyceal clubbing.

There was a calculus in the lower-third of the ureter.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

With chronic kidney disease in pregnancy, the fetal prognosis is best if maternal renal function and blood pressure (BP) are optimized. If the plasma creatinine is < 125 μmol/L, the maternal and perinatal outcome is usually good. If pregnancy occurs with a creatinine > 250 μmol/L, there is a high risk of deterioration in renal function. Between these levels, women should be advised that pregnancy may cause their renal function to deteriorate and that there are also risks to the fetus (mainly fetal growth restriction and preterm delivery). Some renal diseases carry a poorer prognosis than others and specialist advice is required.

Women with CKD should receive pre-pregnancy counselling. The woman should be seen frequently antenatally, particularly in the third trimester. Hypertension should be treated aggressively, U&Es, plasma albumin, urinalysis and midstream urine (MSU) samples checked at each visit, and a protein–creatinine ratio sent each month to quantify proteinuria. Close fetal monitoring is important. It is difficult to distinguish pre-eclampsia from increasing renal compromise, as both may present with hypertension, rising serum creatinine and proteinuria.

Pregnancy should be discouraged in women with CKD 4–5 (estimated glomerular filtration rate eGFR < 30) or on dialysis, as the fetal prognosis is poor. Pregnancy in women who have had a renal transplant is increasingly common and usually successful with good allograft function.

Respiratory disorders

Breathlessness due to the physiological increase in ventilation is a common symptom in pregnancy. Although there is an increased tidal volume from early pregnancy, the exact cause of the feeling of breathlessness is unclear. Investigation should be considered if the breathlessness is of sudden onset, associated with chest pain or if there are clinical signs. It should be remembered that breathlessness can also be a feature of pulmonary thromboembolic disease and heart failure.

Asthma is a common condition. In most women, the disease is unchanged in pregnancy. Treatment is similar to that outside pregnancy and women already established on treatment should continue. Inhaled beta-sympathomimetics and inhaled steroids are considered safe. Oral steroids should be given if clinically indicated.

Thrombocytopenia

Maternal thrombocytopenia in pregnancy

In the second half of normal pregnancies there is a mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count 100–150 × 109/L) in 8% of women, which is not associated with any additional risk to the mother or fetus. The platelet count may also be reduced in pre-eclampsia.

Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura (AITP) is the commonest cause of thrombocytopenia in early pregnancy (but can also arise in later pregnancy) and may be acute or chronic. Antiplatelet antibodies may be detected. These may cross the placenta and, rarely, cause fetal thrombocytopenia, although this seldom is associated with long-term morbidity (cf. alloimmune thrombocytopenia below). No treatment is required in the absence of bleeding, providing the platelet count remains above 50 × 109/L. If the platelet count falls below this level, steroids and/or immunoglobulin can be given. Specialist haematological advice is appropriate before considering treatment.

Fetal (alloimmune) thrombocytopenia

This is a rare disorder, in which there are maternal antibodies to fetal platelets. This has some similarities with rhesus disease, in which there are maternal antibodies to the fetal red cells. The maternal platelet count is normal but there may be profound fetal thrombocytopenia and antenatal or intrapartum fetal intracranial haemorrhage. The diagnosis should be suspected when a previous child has experienced neonatal thrombocytopenia and maternal antiplatelet antibodies have been identified (often to the HPA-1a antigen). Antenatal therapy is either with fetal platelet transfusion and/or maternal immunoglobulin.

Thyroid disorders

In total, 1% of pregnant women in the western world are affected by thyroid disease, with hypothyroidism being commoner than hyperthyroidism. The fetal thyroid gland secretes thyroid hormones from the 12th week and is independent of maternal control.

Hypothyroidism

This may present with fatigue, hair loss, dry skin, abnormal weight gain, poor appetite, cold intolerance, bradycardia and delayed tendon reflexes. If untreated, there is an increase in the rate of spontaneous miscarriages and stillbirths compared with the euthyroid population, as well as a risk of fetal neurological impairment. There is minimal fetal risk if the mother is treated and is euthyroid. Thyroid function should be regularly monitored, aiming to keep TSH and free T4 within the normal range for pregnancy. If the woman is already on treatment and euthyroid at booking, the dose need not be increased.

Hyperthyroidism

Thyrotoxicosis presents with weight loss, exophthalmos, tachycardia and restlessness. It is usually due to Graves disease but may be secondary to a toxic thyroid adenoma or multinodular goitre. Untreated thyrotoxicosis is associated with high fetal mortality and a risk of maternal thyroid crisis at delivery. Well-controlled hyperthyroidism is not associated with an increase in fetal anomalies but there is a tendency for babies to be small for gestational age. Graves disease usually improves during pregnancy.

Carbimazole and propylthiouracil cross the placenta and can potentially cause fetal thyroid suppression in high doses. Radioactive iodine is contraindicated in pregnancy and surgery is indicated only for those with a very large goitre or poor compliance with oral therapy.

Postpartum thyroiditis

This occurs following 5–10% of all pregnancies, usually with initial hyperthyroidism followed by hypothyroidism and then recovery. Because the hypothyroidism occurs at around 1–3 months, the condition may be confused with postnatal depression. Symptoms of hyperthyroidism may be treated with propranolol (antithyroid drugs accelerate the appearance of hypothyroidism). Hypothyroidism should be treated with thyroxine as above, withdrawing around 6 months after delivery. Affected women may require long-term treatment or may develop subsequent hypothyroidism.