Mechanical Ventilation in Pediatric Surgical Disease

Amazingly, ventilation via tracheal cannulation was performed as early as 1543 when Vesalius demonstrated the ability to maintain the beating heart in animals with open chests.1 This technique was first applied to humans in 1780, but there was little progress in positive-pressure ventilation until the development of the Fell–O’Dwyer apparatus. This device provided translaryngeal ventilation using bellows and was first used in 1887 (Fig. 7-1).2,3 The Drinker–Shaw iron lung, which allowed piston-pump cyclic ventilation of a metal cylinder and concomitant negative-pressure ventilation, became available in 1928 and was followed by a simplified version built by Emerson in 1931.4 Such machines were the mainstays in the ventilation of victims of poliomyelitis in the 1930s through the 1950s.

FIGURE 7-1 The Fell–O’Dwyer apparatus that was first used to perform positive-pressure ventilation in newborns. (Reprinted from Matas R. Intralaryngeal insufflation. JAMA 1900;34:1468–73.)

In the 1920s, the technique of tracheal intubation was refined by Magill and Rowbotham.5,6 In World War II, the Bennett valve, which allowed cyclic application of high pressure, was devised to allow pilots to tolerate high-altitude bombing missions.7 Concomitantly, the use of translaryngeal intubation and mechanical ventilation became common in the operating room as well as in the treatment of respiratory insufficiency. However, application of mechanical ventilation to newborns, both in the operating room and in the intensive care unit (ICU), lagged behind that for children and adults.

The use of positive-pressure mechanical ventilation in the management of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) was described in 1962.8 It was the unfortunate death of Patrick Bouvier Kennedy at 32 weeks gestation in 1963 that resulted in additional National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding for research in the management of newborns with respiratory failure.9 The discovery of surfactant deficiency as the etiology of RDS in 1959, the ability to provide positive-pressure ventilation in newborns with respiratory insufficiency in 1965, and demonstration of the effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure in enhancing lung volume and ventilation in patients with RDS in 1971 set the stage for the development of continuous-flow ventilators specifically designed for neonates.10–12 The development of neonatal ICUs (NICUs), hyperalimentation, and neonatal invasive and noninvasive monitoring enhanced the care of newborns with respiratory failure and increased survival in preterm newborns from 50% in the early 1970s to more than 90% today.13

Physiology of Gas Exchange during Mechanical Ventilation

The approach to mechanical ventilation is best understood if the two variables of oxygenation and carbon dioxide elimination are considered separately.14

Carbon Dioxide Elimination

The primary purpose of ventilation is to eliminate carbon dioxide, which is accomplished by delivering tidal volume (Vt) breaths at a designated rate. The product (Vt × rate) determines the minute volume ventilation ( ). Although CO2 elimination is proportional to

). Although CO2 elimination is proportional to  , it is, in fact, directly related to the volume of gas ventilating the alveoli because part of the

, it is, in fact, directly related to the volume of gas ventilating the alveoli because part of the  resides in the conducting airways or in nonperfused alveoli. As such, the portion of the ventilation that does not participate in CO2 exchange is termed the dead space (Vd).15 In a patient with healthy lungs, this dead space is fixed or ‘anatomic’, and consists of about one-third of the tidal volume (i.e., Vd/Vt = 0.33). In a setting of respiratory insufficiency, the proportion of dead space (Vd/Vt) may be augmented by the presence of nonperfused alveoli and a reduction in Vt. Furthermore, dead space can unwittingly be increased through the presence of extensions of the trachea such as the endotracheal tube, a pneumotachometer to measure tidal volume, an end-tidal CO2 monitor, or an extension of the ventilator tubing beyond the ‘Y.’

resides in the conducting airways or in nonperfused alveoli. As such, the portion of the ventilation that does not participate in CO2 exchange is termed the dead space (Vd).15 In a patient with healthy lungs, this dead space is fixed or ‘anatomic’, and consists of about one-third of the tidal volume (i.e., Vd/Vt = 0.33). In a setting of respiratory insufficiency, the proportion of dead space (Vd/Vt) may be augmented by the presence of nonperfused alveoli and a reduction in Vt. Furthermore, dead space can unwittingly be increased through the presence of extensions of the trachea such as the endotracheal tube, a pneumotachometer to measure tidal volume, an end-tidal CO2 monitor, or an extension of the ventilator tubing beyond the ‘Y.’

Tidal volume is a function of the applied ventilator pressure and the volume/pressure relationship (compliance), which describes the ability of the lung and chest wall to distend. At the functional residual capacity (FRC), the static point of end expiration, the tendency for the lung to collapse (elastic recoil) is in balance with the forces that promote chest wall expansion.15 As each breath develops, the elastic recoil of both the lung and chest wall work in concert to oppose lung inflation. Therefore, pulmonary compliance is a function of both the lung elastic recoil (lung compliance) and that of the rib cage and diaphragm (chest wall compliance).

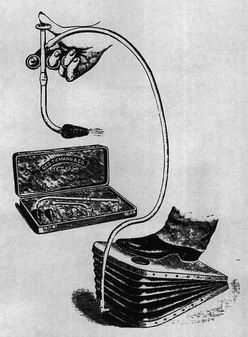

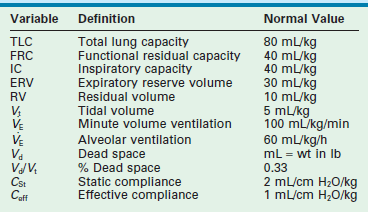

The compliance can be determined in a dynamic or static mode. Figure 7-2 demonstrates the dynamic volume/pressure relationship for a normal patient. Note that application of 25 cmH2O of inflating pressure (ΔP) above static FRC at positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 5 cmH2O generates a Vt of 40 mL/kg. The lung, at an inflating pressure of 30 cmH2O when compared with ambient (transpulmonary) pressure, is considered to be at total lung capacity (TLC) (Table 7-1). Note that the loop observed during both inspiration and expiration is curvilinear. This is due to the resistance that is present in the airways and describes the work required to overcome air flow resistance. As a result, at any given point of active flow, the measured pressure in the airways is higher during inspiration and lower during expiration than at the same volume under zero-flow conditions. Pulmonary compliance measurements, as well as alveolar pressure measurements, can be effectively performed only when no flow is present in the airways (zero flow), which occurs at FRC and TLC. The change observed is a volume of 40 mL/kg and pressure of 25 cmH2O or 1.6 mL/kg/cmH2O. This is termed effective compliance because it is calculated only between the two arbitrary points of end inspiration and end expiration.

FIGURE 7-2 Dynamic pressure/volume relation and effective pulmonary compliance (Ceff) in the normal lung. The volume at 30 cmH2O is considered total lung capacity (TLC). Ceff is calculated by ΔV/ΔP. (Adapted from Bhutani VK, Sivieri EM. Physiological principles for bedside assessment of pulmonary graphics. In: Donn SM, editor. Neonatal and Pediatric Pulmonary Graphics: Principles and Applications. Armonk, NY: Futura Publishing; 1998.)

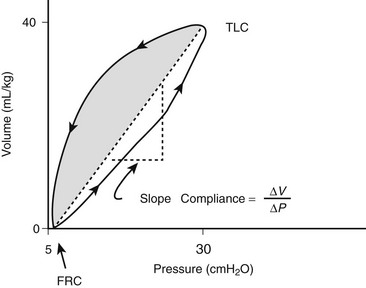

As can be seen from Figure 7-3, the volume/pressure relationship is not linear over the range of most inflating pressures when a static compliance curve is developed. Such static compliance assessments are most commonly performed via a large syringe in which aliquots of 1–2 mL/kg of oxygen, up to a total of 15–20 mL/kg, are instilled sequentially with 3 to 5-second pauses. At the end of each pause, zero-flow pressures are measured. By plotting the data, a static compliance curve can be generated. This curve demonstrates how the calculated compliance can change depending on the arbitrary points used for assessment of the effective compliance (Ceff).16

FIGURE 7-3 Static lung compliance curve in a normal lung. Effective compliance would be altered depending on whether FRC were to be at a level resulting in lung atelectasis (point A) or over distention (point C). Optimal lung mechanics are observed when FRC is set on the steepest portion of the curve (point B). (Adapted from West JB. Respiratory Physiology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1985.)

Alternatively, the pulmonary pressure/volume relationship can be assessed by administration of a slow constant flow of gas into the lungs with simultaneous determination of airway pressure.17,18 A curve may be fitted to the data points to determine the optimal compliance and FRC.19 The compliance will change as the FRC or end-expiratory lung volume (EELV) increases or decreases. For instance, as can be seen in Figure 7-3, at low FRC (point A), atelectasis is present. A given ΔP will not optimally inflate alveoli. Likewise, at a high FRC (point C), because of air trapping or application of high PEEP, the lung is already distended. Application of the same ΔP will result only in over distention and potential lung injury with little benefit in terms of added Vt. Thus, optimal compliance is provided when the pressure/volume range is on the linear portion of the static compliance curve (point B). Clinically, the compliance at a variety of FRC or PEEP values can be monitored to establish optimal FRC.20

Finally, it is important to recognize that a portion of the Vt generated by the ventilator is actually compression of gas within both the ventilator tubing and the airways. The ratio of gas compressed in the ventilator tubing to that entering the lungs is a function of the compliance of the ventilator tubing and the lung. The compliance of the ventilator tubing is 0.3–4.5 mL/cmH2O.21 A change in pressure of 15 cmH2O in a 3 kg newborn with respiratory insufficiency and a pulmonary compliance of 0.4 mL/cmH2O/kg would result in a lung Vt of 18 mL and an impressive ventilator tubing/gas compression volume of 15 mL if the tubing compliance were 1.0 mL/cmH2O. The relative ventilator tubing/gas compression volume would not be as striking in an adult. The ventilator tubing compliance is characterized for all current ventilators and should be factored when considering Vt data. The software in many ventilators corrects for ventilator tubing compliance when displaying Vt values.

Oxygenation

In contrast to CO2 determination, oxygenation is determined by the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) and the degree of lung distention or alveolar recruitment, determined by the level of PEEP and the mean airway pressure (Paw) during each ventilator cycle. If CO2 was not a competing gas at the alveolar level, oxygen within the pulmonary capillary blood would simply be replaced by that provided at the airway, as long as alveolar distention was maintained. Such apneic oxygenation has been used in conjunction with extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal (ECCO2R) or arteriovenous CO2 removal (AVCO2R), in which oxygen is delivered at the carina, whereas lung distention is maintained through application of PEEP.22,23 Under normal circumstances, however, alveolar ventilation serves to remove CO2 from the alveolus and to replenish the PO2, thereby maintaining the alveolar/pulmonary capillary blood oxygen gradient.

Rather than depending on the degree of alveolar ventilation, oxygenation predominantly is a function of the appropriate matching of pulmonary blood flow to inflated alveoli (ventilation/perfusion [ ] matching).15 In normal lungs, the PEEP should be maintained at 5 cmH2O, a pressure that allows maintenance of alveolar inflation at end expiration, balancing the lung/chest wall recoil. An FiO2 of 0.50 should be administered initially. However, one should be able to wean the FiO2 rapidly in a patient with healthy lungs and normal

] matching).15 In normal lungs, the PEEP should be maintained at 5 cmH2O, a pressure that allows maintenance of alveolar inflation at end expiration, balancing the lung/chest wall recoil. An FiO2 of 0.50 should be administered initially. However, one should be able to wean the FiO2 rapidly in a patient with healthy lungs and normal  matching. Areas of ventilation but no perfusion (high

matching. Areas of ventilation but no perfusion (high  ), such as in the setting of pulmonary embolus, do not contribute to oxygenation. Therefore, hypoxemia supervenes in this situation once the average residence time of blood in the remaining perfused pulmonary capillaries exceeds that necessary for complete oxygenation. Normal residence time is threefold that required for full oxygenation of pulmonary capillary blood.

), such as in the setting of pulmonary embolus, do not contribute to oxygenation. Therefore, hypoxemia supervenes in this situation once the average residence time of blood in the remaining perfused pulmonary capillaries exceeds that necessary for complete oxygenation. Normal residence time is threefold that required for full oxygenation of pulmonary capillary blood.

However, the common pathophysiology observed in the setting of respiratory insufficiency is that of minimal or no ventilation, with persistent perfusion (low  ), resulting in right-to-left shunting and hypoxemia. Patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) have collapse of the posterior, or dependent, regions of the lungs when supine.24,25 As the majority of blood flow is distributed to these dependent regions, one can easily imagine the limited oxygen transfer and large shunt secondary to

), resulting in right-to-left shunting and hypoxemia. Patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) have collapse of the posterior, or dependent, regions of the lungs when supine.24,25 As the majority of blood flow is distributed to these dependent regions, one can easily imagine the limited oxygen transfer and large shunt secondary to  mismatch and the resulting hypoxemia that occurs in patients with ARDS. Attempts to inflate the alveoli in these regions, such as with the application of increased PEEP, can reduce

mismatch and the resulting hypoxemia that occurs in patients with ARDS. Attempts to inflate the alveoli in these regions, such as with the application of increased PEEP, can reduce  mismatch and enhance oxygenation.

mismatch and enhance oxygenation.

where FiO2 is the fraction of inspired oxygen, PB is the barometric pressure, PH2O is the partial pressure of water, and RQ is the respiratory quotient or the ratio of CO2 production (VCO2) to oxygen consumption (VO2).

where CvO2, CaO2, and CiO2 are the oxygen contents of venous, arterial, and expected pulmonary capillary blood, respectively.

where Paw represents the mean airway pressure.15

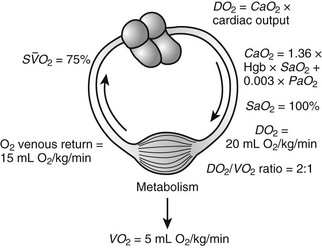

Note that the contribution of the PaO2 to DO2 is minimal and may be disregarded in most circumstances. If the hemoglobin concentration of the blood is normal (15 g/dL) and the hemoglobin is fully saturated with oxygen, the amount of oxygen bound to hemoglobin is 20.4 mL/dL (Fig. 7-4). In addition, approximately 0.3 mL of oxygen is physically dissolved in each deciliter of plasma, which makes the oxygen content of normal arterial blood equal to approximately 20.7 mL O2/dL. Similar calculations reveal that the normal venous blood oxygen content is approximately 15 mL O2/dL.

FIGURE 7-4 Oxygen consumption (VO2) and delivery (DO2) relations. (Adapted with permission from Hirschl RB. Oxygen delivery in the pediatric surgical patients. Opin Pediatr 1994;6:341–7.)

Typically, DO2 is four to five times greater than the associated oxygen consumption (VO2). As DO2 increases or VO2 decreases, more oxygen remains in the venous blood. The result is an increase in the oxygen hemoglobin saturation in the mixed venous pulmonary artery blood ( ). In contrast, if the DO2 decreases or VO2 increases, relatively more oxygen is extracted from the blood, and therefore less oxygen remains in the venous blood. A decrease in

). In contrast, if the DO2 decreases or VO2 increases, relatively more oxygen is extracted from the blood, and therefore less oxygen remains in the venous blood. A decrease in  is the result. In general, the

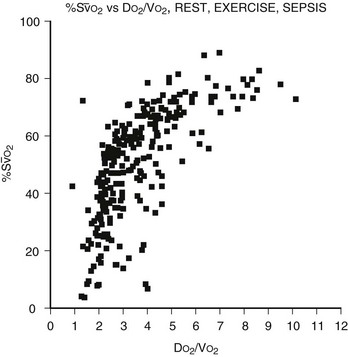

is the result. In general, the  serves as an excellent monitor of oxygen kinetics because it specifically assesses the adequacy of DO2 in relation to DO2 (DO2/VO2 ratio) (Fig. 7-5).26 Many pulmonary arterial catheters contain fiber optic bundles that provide continuous mixed venous oximetry data. Such data provides a means for assessing the adequacy of DO2, rapid assessment of the response to interventions such as mechanical ventilation, and cost savings due to a diminished need for sequential blood gas monitoring.26,27 If a pulmonary artery catheter is unavailable, the central venous oxygen saturation (

serves as an excellent monitor of oxygen kinetics because it specifically assesses the adequacy of DO2 in relation to DO2 (DO2/VO2 ratio) (Fig. 7-5).26 Many pulmonary arterial catheters contain fiber optic bundles that provide continuous mixed venous oximetry data. Such data provides a means for assessing the adequacy of DO2, rapid assessment of the response to interventions such as mechanical ventilation, and cost savings due to a diminished need for sequential blood gas monitoring.26,27 If a pulmonary artery catheter is unavailable, the central venous oxygen saturation ( ) may serve as a surrogate of the

) may serve as a surrogate of the  .28

.28

FIGURE 7-5 The relation of the mixed venous oxygen saturation (SO2) and the ratio of oxygen delivery to oxygen consumption (DO2/VO2) in normal eumetabolic, hypermetabolic septic, and hypermetabolic exercising canines. (Reprinted from Hirschl RB. Cardiopulmonary Critical Care and Shock: Surgery of Infants and Children: Scientific Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997.)

Four factors are manipulated in an attempt to improve the DO2/VO2 ratio: cardiac output, hemoglobin concentration, SaO2, and VO2. The result of various interventions designed to increase cardiac output, such as volume administration, infusion of inotropic agents, administration of afterload-reducing drugs, and correction of acid–base abnormalities, can be assessed by the effect on the  . One of the most efficient ways to enhance DO2 is to increase the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. For instance, an increase in hemoglobin from 7.5 g/dL to 15 g/dL will be associated with a twofold increase in DO2 at constant cardiac output. However, blood viscosity is also increased with blood transfusion, which may result in a reduction in cardiac output.29 The SaO2 can often be enhanced through application of supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation.

. One of the most efficient ways to enhance DO2 is to increase the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. For instance, an increase in hemoglobin from 7.5 g/dL to 15 g/dL will be associated with a twofold increase in DO2 at constant cardiac output. However, blood viscosity is also increased with blood transfusion, which may result in a reduction in cardiac output.29 The SaO2 can often be enhanced through application of supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation.

Assessment of the ‘best PEEP’ identifies the level at which DO2 and  are optimal without compromising compliance.30,31 Evaluation of the best PEEP should be performed in any patient requiring an FiO2 greater than 0.60 and may be determined by continuous monitoring of the

are optimal without compromising compliance.30,31 Evaluation of the best PEEP should be performed in any patient requiring an FiO2 greater than 0.60 and may be determined by continuous monitoring of the  as the PEEP is sequentially increased from 5 cmH2O to 15 cmH2O over a short period. The point at which the

as the PEEP is sequentially increased from 5 cmH2O to 15 cmH2O over a short period. The point at which the  is maximal indicates optimal DO2. The use of PEEP with mechanical ventilation is limited, however, by the adverse effects observed on cardiac output, the effect of barotrauma, and the risk for ventilator-induced lung injury with application of peak inspiratory pressures greater than 30–40 cmH2O.32,33 Furthermore, oxygen consumption can be elevated secondary to sepsis, burns, agitation, seizures, hyperthermia, hyperthyroidism, and increased catecholamine production or infusion. A number of interventions may be applied to reduce VO2, such as sedation and mechanical ventilation. Paralysis may enhance the effectiveness of mechanical ventilation while simultaneously reducing VO2.34,35 In the appropriate setting, hypothermia may be induced with an associated reduction of 7% in VO2 with each 1°C decrease in core temperature.36

is maximal indicates optimal DO2. The use of PEEP with mechanical ventilation is limited, however, by the adverse effects observed on cardiac output, the effect of barotrauma, and the risk for ventilator-induced lung injury with application of peak inspiratory pressures greater than 30–40 cmH2O.32,33 Furthermore, oxygen consumption can be elevated secondary to sepsis, burns, agitation, seizures, hyperthermia, hyperthyroidism, and increased catecholamine production or infusion. A number of interventions may be applied to reduce VO2, such as sedation and mechanical ventilation. Paralysis may enhance the effectiveness of mechanical ventilation while simultaneously reducing VO2.34,35 In the appropriate setting, hypothermia may be induced with an associated reduction of 7% in VO2 with each 1°C decrease in core temperature.36

Mechanical Ventilation

The Mechanical Ventilator and Its Components

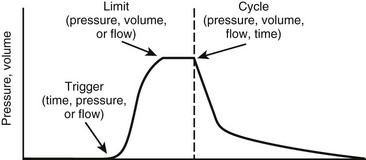

The ventilator must overcome the pressure generated by the elastic recoil of the lung at end inspiration plus the resistance to flow at the airway. To do so, most ventilators in the ICU are pneumatically powered by gas pressurized at 50 pounds per square inch (psi). Microprocessor controls allow accurate management of proportional solenoid-driven valves, which carefully control infusion of a blend of air or oxygen into the ventilator circuit while simultaneously opening and closing an expiratory valve.37 Additional components of a ventilator include a bacterial filter, a pneumotachometer, a humidifier, a heater/thermostat, an oxygen analyzer, and a pressure manometer. A chamber for nebulizing drugs is usually incorporated into the inspiratory circuit. The Vt is not usually measured directly. Rather, flow is assessed as a function of time, thereby allowing calculation of Vt. The modes of ventilation are characterized by three variables that affect patient and ventilator synchrony or interaction: the parameter used to initiate or ‘trigger’ a breath, the parameter used to ‘limit’ the size of the breath, and the parameter used to terminate inspiration or ‘cycle’ the breath (Fig. 7-6).38

The magnitude of the breath is controlled or limited by one of three variables: pressure, volume, or flow. When a breath is volume, pressure, or flow ‘controlled,’ it indicates that inspiration concludes once the limiting variable is reached. Pressure-controlled or pressure-limited modes are the most popular for all age groups, although volume-control ventilation may be of advantage in preterm newborns.39,40 In the pressure modes, the respiratory rate, the inspiratory gas flow, the PEEP level, the inspiratory/expiratory (I/E) ratio, and the Paw are determined. The ventilator infuses gas until the desired peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) is provided. Zero-flow conditions are realized at end inspiration during pressure-limited ventilation. Therefore, in this mode, PIP is frequently equivalent to end-inspiratory pressure (EIP) or plateau pressure.

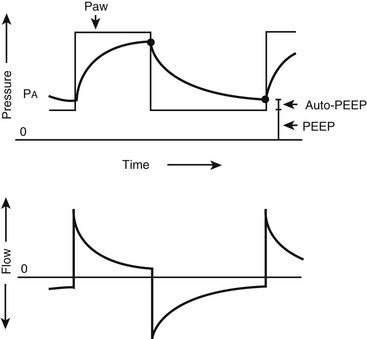

In many ventilators, the gas flow rate is fixed, although some ventilators allow manipulation of the flow rate and therefore the rate of positive-pressure development. Those with rapid flow rates will provide rapid ascent of pressure to the preset maximum, where it will remain for the duration of the inspiratory phase. This ‘square wave’ pressure pattern results in decelerating flow during inspiration (Fig. 7-7). Airway pressure is ‘front loaded,’ which increases Paw, alveolar volume, and oxygenation without increasing PIP.41 However, one of the biggest advantages of pressure-controlled or pressure-limited ventilation is the ability to avoid lung over-distention and barotrauma/volutrauma (discussed later). The disadvantage of pressure-controlled or pressure-limited ventilation is that delivered volume varies with airway resistance and pulmonary compliance, and may be reduced when short inspiratory times are applied (Fig. 7-8).42 For this reason, both Vt and  must be monitored carefully.

must be monitored carefully.

FIGURE 7-7 Pressure and flow waveforms during pressure-limited, time-cycled ventilation. Decelerating flow is applied, which ‘front loads’ the pressure during inspiration. Auto-positive end-expiratory pressure is present when the expiratory time is inadequate for complete expiration. (Reprinted from Marini JJ. New options for the ventilatory management of acute lung injury. New Horiz 1993;1:489–503.)

FIGURE 7-8 Effect of rate on tidal volume (Vd/Vt) and minute ventilation (VE) during pressure-limited ventilation. Note that VE remains unchanged above 20 breaths/min. Simultaneously, Vd/Vt and PaCO2 increase, despite an increase in respiratory rate. (Reprinted from Nahum A, Burke WC, Ravenscraft SA. Lung mechanics and gas exchange during pressure-control ventilation in dogs: Augmentation of CO2 elimination by an intratracheal catheter. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;146:965–73.)

Volume-controlled or volume-limited ventilation requires delineation of the Vt, respiratory rate, and inspiratory gas flow. Gas will be inspired until the preset Vt is attained. The volume will remain constant despite changes in pulmonary mechanics, although the resulting EIP and PIP may be altered. Flow-controlled or flow-limited ventilation is similar in many respects to volume-controlled or volume-limited ventilation. A flow pattern is predetermined, which effectively results in a fixed volume as the limiting component of inspiration.

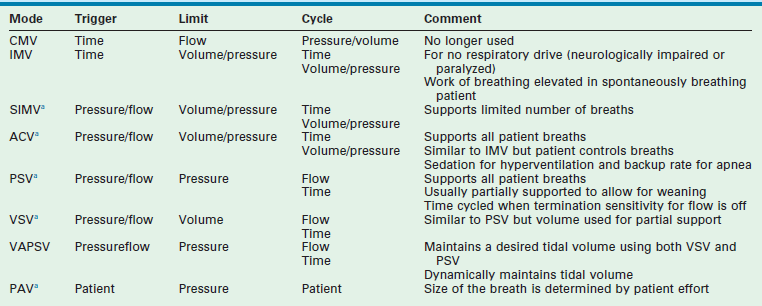

Modes of Ventilation (Table 7-2)

Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation

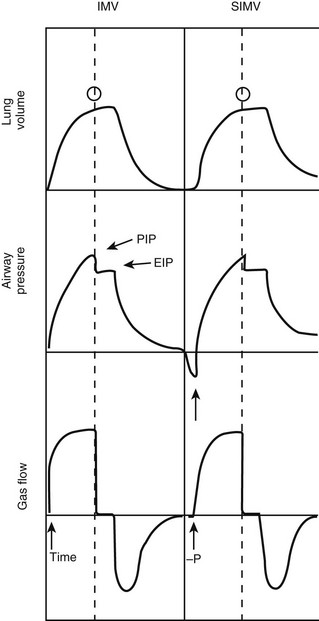

Intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV) is time triggered, volume or pressure limited, and either time, volume, or pressure cycled. A rate is set, as is a volume or pressure parameter. Additional inspired gas is provided by the ventilator to support spontaneous breathing when additional breaths are desired. The difference between CMV and IMV is that, in the IMV mode, inspired gases are provided to the patient during spontaneous breaths.43 IMV is useful in patients who do not have respiratory drive such as those who are neurologically impaired or pharmacologically paralyzed. Work of breathing is still elevated with this mode in the awake and spontaneously breathing patient.

Synchronized Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation

In the SIMV mode, the ventilator synchronizes IMV breaths with the patient’s spontaneous breaths (Fig. 7-9). Small, patient-initiated negative deflections in airway pressure (pressure triggered) or decreases in the constant ventilator gas flow (bias flow) passing through the exhalation valve (flow triggered) provide a signal to the ventilator that a patient breath has been initiated. Ventilated breaths are timed with the patient’s spontaneous respiration, but the number of supported breaths each minute is predetermined and remains constant. Additional constant inspired gas flow is provided for use during any other spontaneous breaths. Advances in neonatal ventilators have provided the means for detecting small alterations in bias flow. As such, flow-triggered SIMV can be applied to newborns, which appears to enhance ventilatory patterns and allows ventilation with reduced airway pressures and FiO2.44,45 SIMV may be associated with a reduction in the duration of ventilation and the incidence of air leak in newborns in general, as well as in those premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and intraventricular hemorrhage.46,47

FIGURE 7-9 Pressure, volume, and flow waveforms observed during intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV) and synchronized IMV (SIMV). In this case, an end-inspiratory pause has been added. Note the difference between peak (PIP) and end-inspiratory (EIP) or plateau pressure. Arrows, triggering variables; open circles, cycling variables. (Adapted from Bartlett RH. Use of the Mechanical Ventilator: Surgery. New York: Scientific American; 1988.)

Assist-Control Ventilation

In the spontaneously breathing patient, brain stem reflexes dependent on cerebrospinal fluid levels of CO2 and pH can be harnessed to determine the appropriate breathing rate.15 As in SIMV, with assist-control ventilation (ACV) the assisted breaths can be either pressure triggered or flow triggered. The triggering-mechanism sensitivity can be set in most ventilators. In contrast to SIMV, the ventilator supports all patient-initiated breaths. This mode is similar to IMV but allows the patient inherently to control the ventilation and minimizes patient work of breathing in adults and neonates.48,49 Occasionally, patients may hyperventilate, such as when they are agitated or have neurologic injury. Heavy sedation may be required if agitation is present. A minimal ventilator rate below the patient’s assist rate should be established in case of apnea.

Pressure Support Ventilation

Pressure support ventilation (PSV) is a pressure- or flow-triggered, pressure-limited, and flow-cycled mode of ventilation. It is similar in concept to ACV, in that mechanical support is provided for each spontaneous breath and the patient determines the ventilator rate. During each breath, inspiratory flow is applied until a predetermined pressure is attained.50 As the end of inspiration approaches, flow decreases to a level below a specified value (2–6 L/min) or a percentage of peak inspiratory flow (at 25%). At this point, inspiration terminates. Although it may apply full support, PSV is frequently used to support the patient partially by assigning a pressure limit for each breath that is less than that required for full support.51 For example, in the spontaneously breathing patient, PSV can be sequentially decreased from full support to a PSV 5–10 cmH2O above PEEP, allowing weaning while providing partial support with each breath.52,53 Thus, Vt during PSV may be dependent on patient effort. PSV provides two advantages during ventilation of spontaneously breathing patients: (1) it provides excellent support and decreases the work of breathing associated with ventilation; and (2) it lowers PIP and Paw while higher Vt and cardiac output levels may be observed.50,54,55

Volume Support Ventilation

Volume support ventilation (VSV) is similar to PSV except that a volume, rather than a pressure, is assigned to provide partial support. Automation with VSV is enhanced because there is less need for manual changes to maintain stable tidal and minute volume during weaning.56 Both VSV and PSV are equally effective at weaning infants and children from the ventilator.57

Volume-Assured Pressure Support Ventilation

Volume-assured pressure support ventilation (VAPSV) attempts to combine volume- and pressure-controlled ventilation to ensure a desired Vt within the constraints of the pressure limit. It has the advantage of maintaining inflation to a point below an injurious PIP level while maintaining Vt constant in the face of changing pulmonary mechanics. Work of breathing may be markedly decreased while Ceff is increased during VAPSV.58

Proportional Assist Ventilation

Proportional assist ventilation (PAV) is an intriguing approach in the spontaneously breathing patient. It relies on the concept that the combined pressure generated by the ventilator (Paw) and respiratory muscles (Pmus) is equivalent to that required to overcome the resistance to flow of the endotracheal tube/airways (Pres) and the tendency for the inflated lungs to collapse.59

With PAV, airway pressure generation by the ventilator is proportional at any instant to the respiratory effort (Pmus) generated by the patient. Small efforts, therefore, result in small breaths, whereas greater patient effort results in development of a greater Vt. Inspiration is patient triggered and terminates with discontinuation of patient effort. Rate, Vt, and inspiratory time are entirely patient controlled. The predominant variable controlled by the ventilator is the proportional response between Pmus and the applied ventilator pressure. This proportional assist (Paw/Pmus) can be increased until nearly all patient effort is provided by the ventilator.60 Patient work of breathing, dyspnea, and PIP are reduced.61,62 Elastance and resistance are set, as is applied PEEP. Vt is variable, and the risk of atelectasis is present. PAV produces similar gas exchange with lower airway pressures when compared with conventional ventilation in infants.63 Compared with preterm newborns being ventilated with the assist-control mode and with IMV, preterm newborns managed with PAV maintained gas exchange with lower airway pressures and a decrease in the oxygenation index by 28%.64 Chest wall dynamics also are enhanced.65 PAV represents an exciting first step in servoregulating ventilators to patient requirements. Additional studies using neutrally adjusted ventilation are also underway and certain populations (obstructive lung disease and small children) may benefit from the increased patient-ventilator synchrony.66,67

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure

During continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), pressures greater than those of ambient pressure are continuously applied to the airways to enhance alveolar distention and oxygenation.68 Both airway resistance and work of breathing may be substantially reduced. Since ventilation is unsupported, this mode requires that the patient provides all of the work of breathing and CPAP should be avoided in patients with hypovolemia, untreated pneumothorax, lung hyperinflation, or elevated intracranial pressure, and in infants with nasal obstruction, cleft palate, tracheoesophageal fistula, or untreated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. CPAP is frequently applied via nasal prongs, although it can be delivered in adult patients with a nasal mask.

Bilevel Control of Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP)

Although sometimes used in the setting of acute lung injury, BiPAP is frequently used for home respiratory support by varying airway pressure between one of two settings: the inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and the expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP).69,70 With patient effort, a change in flow is detected, and the IPAP pressure level is developed. With reduced flow at end expiration, EPAP is re-established. Therefore, this device provides both ventilatory support and airway distention during the expiratory phase; however, BiPAP ventilators should be used only to support the patient who is spontaneously breathing. In fact, in a randomized trial of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) in a subset of pediatric patients with lung injury, NIV improved hypoxemia and decreased the rate of endotracheal intubation.71 In neonates, a multicenter randomized trial demonstrated decreased days of mechanical ventilation, chronic lung disease, and mortality when early CPAP was used instead of intubation and surfactant in preterm infants.72

Inverse Ratio Ventilation

In the setting of respiratory failure, it would be helpful to enhance alveolar distention to reduce hypoxemia and shunt. One means to accomplish this is to maintain the inspiratory plateau pressure for a longer proportion of the breath.73 The inspiratory time may be prolonged to the point at which the I/E ratio may be as high as 4 : 1.74 In most circumstances, however, the I/E ratio is maintained at approximately 2 : 1. Inverse ratio ventilation (IRV) is usually performed during pressure-controlled ventilation (PC-IRV), although prolonged inspiratory times can be applied during volume-controlled ventilation by adding a decelerating flow pattern or an end-inspiratory pause to the volume-controlled ventilator breath.75 One advantage of IRV is the ability to recruit alveoli that are associated with high-resistance airways that inflate only with prolonged application of positive pressure.76 Unfortunately, IRV is associated with a profound sense of dyspnea in patients who are awake and spontaneously breathing. Therefore, heavy sedation and pharmacologic paralysis is required during this ventilator mode.

As Et is reduced, the risk for incomplete expiration, identified by the failure to achieve zero-flow conditions at end expiration, is increased. This results in ‘auto-PEEP’ or a total PEEP greater than that of the preset or applied PEEP. Care should be taken to recognize the presence of auto-PEEP and to incorporate it into the ventilation strategy to avoid barotrauma.77 IRV also may negatively affect cardiac output and, therefore, decrease DO2.78 Some studies using IRV revealed an increase in Paw and oxygenation while protecting the lungs by reducing PIP.79–82 Other reports suggest that early implementation of IRV in severe ARDS enhances oxygenation and allows reduction in FiO2, PEEP, and PIP.83 On the contrary, a number of studies have failed to demonstrate enhanced gas exchange with this mode of ventilation. Some series have suggested that IRV is less effective at enhancing gas exchange than is application of PEEP to maintain the same mean airway pressure.84 Overall, it appears that oxygenation is determined primarily by the mean airway pressure rather than specifically by the application of IRV. As such, the usefulness of IRV remains in question.85

Airway Pressure Release Ventilation

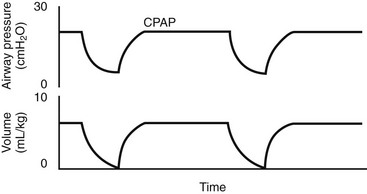

Airway pressure release ventilation (APRV) is a unique approach to ventilation in which CPAP at high levels is used to enhance mean alveolar volume while intermittent reductions in pressure to a ‘release’ level provide a period of expiration (Fig. 7-10). Re-establishment of CPAP results in inspiration and return of lung volume back to the baseline level. The advantage of APRV is a reduction in PIP of approximately 50% in adult patients with ARDS when compared with other more conventional modes of mechanical ventilation.86,87 Spontaneous ventilation also is allowed throughout the cycle, which may enhance cardiac function and renal blood flow.88,89 Some data suggest that  matching may beimproved and dead space reduced.90,91 In performing APRV, tidal volume is altered by adjusting the release pressure. Conceptually, ventilator management during APRV is the inverse of other modes of positive-pressure ventilation in that the PIP, or CPAP, determines oxygenation, while the expiratory pressure (release pressure) is used to adjust Vt and CO2 elimination.

matching may beimproved and dead space reduced.90,91 In performing APRV, tidal volume is altered by adjusting the release pressure. Conceptually, ventilator management during APRV is the inverse of other modes of positive-pressure ventilation in that the PIP, or CPAP, determines oxygenation, while the expiratory pressure (release pressure) is used to adjust Vt and CO2 elimination.

FIGURE 7-10 Typical pressure and volume waveforms observed during airway pressure release ventilation (APRV).

APRV is very similar to modes of ventilation, such as IRV, that use prolonged I/E ratios; however, APRV appears to be better tolerated when compared with IRV in patients with acute lung injury/ARDS, as demonstrated by a reduced need for paralysis and sedation, increased cardiac performance, decreased pressor use, and decreased PIP requirements.92 APRV improved the lung perfusion, as measured by pulmonary blood flow and oxygen delivery, in infants who underwent repair of tetralogy of Fallot or cavopulmonary shunt.93 However, the overall clinical experience with APRV is limited in the pediatric population.94,95

Management of the Mechanical Ventilator

IMV and SIMV may suffice for patients with normal lungs, such as when needed after an operation.96 If the patient is spontaneously breathing and is to be ventilated for more than a brief period, a flow- or pressure-triggered assist mode, pressure support, or PAV will result in maximal support and minimal work of breathing.48,49 Ventilator modes that allow adjustment of specific details of pressure, flow, and volume are required in the patient with severe respiratory failure. With all these modes, the ventilator rate, Vt or PIP, PEEP, and either inspiratory time alone or I/E ratio (if ventilation is pressure limited) must be assigned. Other secondary controls such as the flow rate, the flow pattern, the trigger sensitivity for assisted breaths, the inspiratory hold, the termination sensitivity, and the safety pressure limit also are set on individual ventilators. The normal  is 100–150 mL/kg/min. The FiO2 is usually initiated at 0.50 and decreased based on pulse oximetry. All efforts should be made to maintain the FiO2 less than 0.60 to avoid alveolar nitrogen depletion and the development of atelectasis.97,98 Oxygen toxicity likely is a result of this phenomenon, although free oxygen radical formation may play a role when an FiO2 greater than 0.40 is applied for prolonged periods.99 A short inspiratory phase with a low I/E ratio favors the expiratory phase and CO2 elimination, whereas longer I/E ratios enhance oxygenation. In the normal lung, I/E ratios of 1 : 3 and inspiratory time of 0.5 to 1 second are typical.

is 100–150 mL/kg/min. The FiO2 is usually initiated at 0.50 and decreased based on pulse oximetry. All efforts should be made to maintain the FiO2 less than 0.60 to avoid alveolar nitrogen depletion and the development of atelectasis.97,98 Oxygen toxicity likely is a result of this phenomenon, although free oxygen radical formation may play a role when an FiO2 greater than 0.40 is applied for prolonged periods.99 A short inspiratory phase with a low I/E ratio favors the expiratory phase and CO2 elimination, whereas longer I/E ratios enhance oxygenation. In the normal lung, I/E ratios of 1 : 3 and inspiratory time of 0.5 to 1 second are typical.

Strategies in Respiratory Failure

Preventing Ventilator-Induced Lung Injury

A decrease in pulmonary compliance and FRC is seen in the patient with acute lung injury (PaO2/FiO2 ratio, 200–300) or ARDS (PaO2/FiO2 ratio, <200). This is secondary to alveolar collapse and a decrease in the volume of lung available for ventilation and, in turn, to decreased pulmonary compliance. As a result, higher ventilator pressures are necessary to maintain Vt and  . However, any attempt to ventilate the patient with respiratory insufficiency due to parenchymal disease with higher pressures can result in compromise of cardiopulmonary function and the development of ventilator-induced lung injury.100

. However, any attempt to ventilate the patient with respiratory insufficiency due to parenchymal disease with higher pressures can result in compromise of cardiopulmonary function and the development of ventilator-induced lung injury.100

The concept of ventilator-induced lung injury was first identified in 1974 by demonstrating the detrimental effects of ventilation at PIP of 45 cmH2O in rats.101 Electron microscopy has been used to document an increased incidence of alveolar stress fractures in ex-vivo, perfused rabbit lungs exposed to transalveolar pressures more than 30 cmH2O.102 Other studies have demonstrated increases in albumin leak, elevation of the capillary leak coefficient, enhanced wet-to-dry lung weight, deterioration in gas exchange, and augmented diffuse alveolar damage on histology with application of increased airway pressure (45–50 cmH2O) in otherwise normal rats and sheep over a 1- to 24-hour period.31,103,104 Pulmonary exposure to high pressures may potentially worsen nascent respiratory insufficiency and, ultimately, lead to the development of pulmonary fibrosis.

Such injury may be prevented during application of high PIPs by strapping the chest, thereby preventing lung over-distention, suggesting that alveolar distention or ‘volutrauma’ is the injurious element, rather than application of high pressures or ‘barotrauma’.105 A low-Vt (6 mL/kg) approach to mechanical ventilation in rabbits with Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced acute lung injury appears to be associated with enhancement in oxygenation, increase in pH, increase in arterial blood pressure, and decrease in extravascular lung water when compared with a high-Vt group (15 mL/kg).106 A relation may also exist between ventilator gas flow rate and the development of lung injury.107 Positive blood cultures were found in five of six animals exposed to high EIP, but rarely in those with low EIP.108

Together, the above data suggest that the method of ventilation has an effect on lung function and gas exchange as well as a systemic effect, which may include translocation of bacteria from the lungs. As such, avoidance of high PIPs and lung over-distention should be a primary goal of mechanical ventilation. Although the animal data suggests that high PIPs and volumes may be deleterious, two multicenter studies have attempted to randomize patients with ARDS to high and low peak pressure or volume strategies. The first failed to demonstrate a difference in mortality or duration of mechanical ventilation in patients randomized to either the low-volume (7.2 ± 0.8 mL/kg) or the high-volume (10.8 ± 1.0 mL) strategy, although the applied PIP was not elevated to what would commonly be considered injurious levels in either group (low, 23.6 ± 5.8 cmH2O; high, 34.0 ± 11.0 cmH2O).109 Another study found similar results, but had similar design limitations.110 A survival increase from 38% to 71% at 28 days, a higher rate of weaning from mechanical ventilation, and a lower rate of barotrauma has been demonstrated in patients in whom a lung-protective ventilator strategy was used. This strategy consisted of lung distention to a level that prevented alveolar collapse during expiration (see later) and avoidance of high distending pressures.111 One study identified a significant reduction over time in bronchoalveolar lavage concentrations of polymorphonuclear cells (P < 0.001), interleukin (IL)-1β (P < 0.05), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (P < 0.001), interleukin (IL)-8 (P < 0.001), and IL-6 (P < 0.005) and in the plasma concentration of IL-6 (P < 0.002) among 44 patients randomized to receive a lung-protective strategy rather than a conventional approach.112 The mean number of ventilator-free days at 28 days in the lung-protective strategy group was higher than in the control group (12 ± 11 vs. 4 ± 8 days, respectively; P < 0.01). However, mortality rates at 28 days from admission were not different.

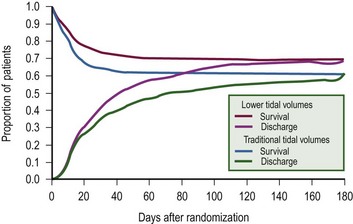

The NIH’s Acute Respiratory Distress Network convincingly demonstrated that mortality was reduced with the use of a low-volume (6 mL/kg, mortality of 31%) when compared with a high-volume (12 mL/kg, mortality of 39%; P = 0.005) ventilator approach (Fig. 7-11).113 Interestingly, no difference was found in gas exchange or pulmonary mechanics between groups to account for the difference in mortality. The majority of clinicians are now convinced that avoidance of high PIP and support of lung recruitment, through the application of appropriate levels of PEEP (see later), should be a primary goal of any mechanical ventilatory program.

FIGURE 7-11 Probability of survival and of being discharged home and breathing without assistance during the first 180 days after randomization in patients with acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The status at 180 days or at the end of the study was known for all but nine patients. (From The Acute Respiratory Distress Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1301–8.)

Permissive Hypercapnia

To avoid ventilator-induced lung injury, practitioners have applied the concept of permissive hypercapnia. With this approach, PaCO2 is allowed to increase to levels as high as 120 mmHg as long as the blood pH is maintained in the 7.1–7.2 range by administration of buffers.114 Mortality was reduced to 26% when compared with that expected (53%; P < 0.004) based on Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) scores when low-volume, pressure-limited ventilation with permissive hypercapnia was applied in the setting of ARDS in adults.115 For burned children, the mortality rate was only 3.7% despite a high degree of inhalation injury when a ventilator strategy used a PIP of 40 cmH2O and accepted an elevated PaCO2 as long as the arterial pH was greater than 7.20.116 Other studies suggested that a strategy of high-frequency (40–120 breaths/min) ventilation with a low Vt, low PIP, high PEEP (7–30 cmH2O), and mild hypercapnia (PaCO2 from 45 to 60 mmHg) enhances the survival rate in children with severe ARDS.117

Using Protective Effects of PEEP

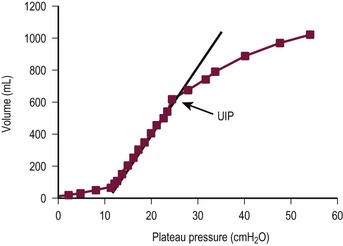

Although application of high, over distending airway pressures appears to be associated with the development of lung injury, a number of studies have demonstrated that application of PEEP or high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) may prevent lung injury by the following mechanisms: (1) recruitment of collapsed alveoli, which reduces the risk for over-distention of healthy units; (2) resolution of alveolar collapse, which in and of itself is injurious; and (3) avoidance of the shear forces associated with the opening and closing of alveoli.118,119 In the older child with injured lungs, a pressure of 8–12 cmH2O is required to open alveoli and to begin Vt generation.111,120,121 Alveoli will subsequently close unless the end-expiratory pressure is maintained at such pressures, and cyclic opening and closing is thought to be particularly injurious because of application of large shear forces.120 One way to avoid this process is through the application of PEEP to a point above the inflection pressure (Pflex), such that alveolar distention is maintained throughout the ventilatory cycle (Fig. 7-12).122,123 In addition, as mentioned previously, it has been demonstrated that the distribution of infiltrates and atelectasis in the supine patient with ARDS is predominantly in the dependent regions of the lung.124 This is likely the result of compression due to the increased weight of the overlying edematous lung. It has been shown that when the superimposed gravitational pressure from the weight of the overlying lung exceeded the PEEP applied to a given region of the lung, end-expiratory lung collapse increased, resulting in de-recruitment.125 Thus, application of PEEP may result in recruitment of these atelectatic lung regions, simultaneously enhancing pulmonary compliance and oxygenation. PEEP and prone positioning (see later) are more effective if the need for ventilation is of extrapulmonary etiology rather than pulmonary etiology.126

FIGURE 7-12 Static pressure/volume curve demonstrating the Pflex point in a patient with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Positive end-expiratory pressure should be maintained approximately 2 cmH2O above that point. The upper inflection point (UIP) indicates the point at which lung over distention is beginning to occur. Ventilation to points above the UIP should be avoided in most circumstances. (Reprinted from Roupie E, Dambrosio M, Servillo G. Titration of tidal volume and induced hypercapnia in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:121–8.)

As a result of these new data and concepts, the approach to mechanical ventilation in the patient with respiratory failure has changed drastically over the past few years (Box 7-1). Time-cycled, pressure-controlled ventilation has become favored because of the ability to limit EIP to noninjurious levels at a maximum of 35 cmH2O.121 In infants and newborns, this EIP limit is set lower at 30 cmH2O. The Vt should be maintained in the range of 6 mL/kg.113 A lung-protective approach also incorporates lung distention and prevention of alveolar closure. Pressure/volume curves should be developed on each patient at least daily so that the Pflex can be identified and the PEEP maintained above Pflex. If a pressure/volume curve cannot be determined, then Pflex can be assumed to be in the 7–12 cmH2O range, and PEEP, at that level or up to 2 cmH2O higher, can be applied.121,127,128 Recruitment maneuvers that use intermittent sustained inflations of approximately 40 cmH2O for up to 40 seconds often can be beneficial by initially inflating collapsed lung regions.129 The inflation obtained with the recruitment maneuver is then sustained by maintaining PEEP greater than Pflex.

As both PIP and PEEP are increased, enhancements in compliance and reductions in Vd/Vt and shunt are to be expected. If they are not observed, then one should suspect the presence of over-distention of currently inflated alveoli instead of the desired recruitment of collapsed lung units. Application of increased levels of PEEP also may result in a decrease in venous return and cardiac output. In addition, West’s zone I physiology, which predicts diminished or absent pulmonary capillary flow in the nondependent regions of the lungs at end inspiration, may be exacerbated with application of higher airway pressures. This may be especially detrimental, because it is the nondependent regions that are best inflated and to which one would wish to direct as much pulmonary blood flow as possible.15 As a result, parameters of DO2 should be carefully monitored during application of increased PEEP.130 One approach for monitoring delivery is by applying close attention to the SVO2 whenever the PEEP is increased to more than 5 cmH2O.

If oxygenation remains inadequate with application of higher levels of PEEP, FiO2 should be increased to maintain SaO2 greater than 90%, although levels as low as 80% may be acceptable in patients with adequate DO2. As mentioned previously, one of the most effective ways to enhance DO2 is with transfusion. All attempts should be made to avoid the atelectasis and oxygen toxicity associated with FiO2 levels greater than 0.60.97 Extending FiO2 to levels more than 0.60 often has little effect on oxygenation, because severe respiratory failure is frequently associated with a large transpulmonary shunt. If inadequate DO2 persists, a trial increase in PEEP level should be performed or institution of extracorporeal support considered.131 Inflation of the lungs also can be enhanced by prolonging the inspiratory time by PC-IRV. Pharmacologic paralysis and sedation are required during performance of PC-IRV, and paralysis may have the additional benefit of decreasing oxygen consumption and enhancing ventilator efficiency.35 PaO2 may improve with application of PC-IRV.132,133 Monitoring the effect on DO2 and  is critical to ensure the benefit of this intervention. The advantages of the alveolar inflation associated with a decelerating flow waveform during pressure-limited modes of ventilation also should be used.41

is critical to ensure the benefit of this intervention. The advantages of the alveolar inflation associated with a decelerating flow waveform during pressure-limited modes of ventilation also should be used.41

Prone Positioning

Altering the patient from the supine to the prone position appears to enhance gas exchange.134,135 Enhanced blood flow to the better-inflated anterior lung regions with the prone position would logically appear to account for this increase in oxygenation. However, data in oleic acid lung-injured sheep suggest that the enhancement in gas exchange may be due predominantly to more homogeneous distribution of ventilation, rather than to redistribution of pulmonary blood flow, because lung distention is more uniform in the prone position.136–138 This effect may be reversed after a number of hours. Enhanced posterior region lung inflation frequently accounts for persistent increases in oxygenation when the patient is returned to the supine position. Therefore, benefit may be seen when the prone and supine positions are alternated, usually every four to six hours.124 A randomized, controlled, multicenter trial evaluating the effectiveness of the prone position in the treatment of patients with ARDS was recently completed.139 One group was placed in the prone position for 6 or more hours daily for ten days while the control group remained in the supine position. Although the PaO2/FiO2 ratio was greater in the prone when compared with the supine group (prone, 63.0 + 66.8, vs supine, 44.6 + 68.2; P = 0.02), no difference in mortality was noted between groups. It is clear that some patients will not respond to altered positioning, in which case this adjunct should be discontinued. Meticulous attention to careful patient padding and avoidance of dislodgement of tubes and catheters is of the utmost importance in successful implementation of this approach.

Adjunctive Maneuvers

Another means for enhancing oxygenation is through administration of diuretics and the associated reduction of left atrial and pulmonary capillary hydrostatic pressure.140 Diuresis results in a decrease in lung interstitial edema. In addition, reduction of lung edema decreases compression of the underlying dependent lung.141 Collapsed dependent lung regions are thereby recruited. Although this treatment approach has not been proved in randomized clinical trials, reduction in total body fluid in adult patients with ARDS appears to be associated with an increase in survival.142 One must be cognizant of the risks of hypoperfusion and organ system failure, especially renal insufficiency, if overly aggressive diuresis is performed. Overall, however, a strategy of fluid restriction and diuresis should be pursued in the setting of ARDS, while monitoring organ perfusion and renal function.143 In a randomized trial, a conservative fluid management strategy improved the oxygenation index, the lung injury score, the ventilator-free days, and the number of days spent out of the ICU while the prevalence of shock and use of dialysis did not increase.144 Although the study was limited to 60 days, the results further support keeping a patient with acute lung injury in a state of fluid balance.

Applying noninjurious PIPs and enhancing PEEP levels limits the ΔP (the amplitude between the PIP and the PEEP) and Vt, and compromises CO2 elimination. Therefore, the concept of permissive hypercapnia, which was discussed previously, is integral to the successful application of lung-protective strategies. PaCO2 levels greater than 100 mmHg have been allowed with this approach, although most practitioners prefer to maintain the PaCO2 at less than 60–70 mmHg.115 Bicarbonate or tris-hydroxymethyl-aminomethane (THAM) can be used to induce a metabolic alkalosis to maintain the pH at greater than 7.20. Few significant physiologic effects are observed with elevated PaCO2 levels as long as the pH is maintained at reasonable levels.145 If adequate CO2 elimination cannot be achieved while limiting EIP to noninjurious levels, then initiation of extracorporeal life support (ECLS) should be considered.

The one situation in which it may be acceptable to increase EIP to levels greater than 35 cmH2O (30 cmH2O in the infant and newborn) is in the patient with reduced chest wall compliance and relatively normal pulmonary compliance. As pulmonary compliance is a combination of lung compliance and chest wall compliance, a decrease in chest wall compliance, such as due to abdominal distention, obesity, or chest wall edema, can markedly reduce pulmonary compliance despite reasonable lung compliance. This situation is analogous to studies discussed previously in which the lungs remain uninjured despite application of high airway pressures because the chest is strapped to prevent lung over distention.105 This is a frequent problem in secondary respiratory failure due to trauma, sepsis, and other disease processes observed among surgical patients, including tightly placed dressings. A cautious increase in EIP in such patients may be warranted. Finally, a simple intervention, such as raising the head of the bed, may have marked effects on FRC and gas exchange in such patients.

Weaning From Mechanical Ventilation

Once a patient is spontaneously breathing and able to protect the airway, consideration is given to weaning from ventilator support. Weaning in the majority of children should take 2 days or less.57 The Fi O2 should be decreased to less than 0.40 before extubation. Simultaneously, PEEP should be lowered to 5 cmH2O. The pressure support mode of ventilation is an efficient means for weaning because the preset inspiratory pressure can be gradually decreased while partial support is provided for each breath.146 Adequate gas exchange with a pressure support of 7–10 cmH2O above PEEP in adults and newborns is predictive of successful extubation.147 Another study in adults demonstrated that simple transition from full ventilator support to a ‘T-piece,’ in which oxygen flow-by is provided, is as effective at weaning as is gradual reduction in rate during IMV or pressure during PSV.148 In all circumstances, brief trials of spontaneous breathing before extubation should be performed with flow-by oxygen and CPAP. Prophylactic dexamethasone administration does not appear to increase the odds of a successful extubation in infants, except in ‘high risk’ patients who receive multiple doses starting at least four hours before extubation.149,150 Parameters during a T-piece trial that indicate readiness for extubation include the following: (1) maintenance of the pretrial respiratory and heart rates; (2) inspiratory force greater than 20 cmH2O; (3)  less than 100 mL/kg/min; and (4) SaO2 greater than 95%. If the patient’s status is unclear, transcutaneous CO2 monitoring, along with arterial blood gas analysis (PaCO2 < 40 mmHg; PaO2 > 60 mmHg), may help in determining whether extubation is appropriate. The weaning trial should be brief, and under no circumstances should it last longer than one hour. In most cases, the patient who tolerates spontaneous breathing through an endotracheal tube for only a few minutes will demonstrate enhanced capabilities once the tube is removed.

less than 100 mL/kg/min; and (4) SaO2 greater than 95%. If the patient’s status is unclear, transcutaneous CO2 monitoring, along with arterial blood gas analysis (PaCO2 < 40 mmHg; PaO2 > 60 mmHg), may help in determining whether extubation is appropriate. The weaning trial should be brief, and under no circumstances should it last longer than one hour. In most cases, the patient who tolerates spontaneous breathing through an endotracheal tube for only a few minutes will demonstrate enhanced capabilities once the tube is removed.

Frequent causes of failed extubation include persistent pulmonary parenchymal disease, interstitial fibrosis, and reduced breathing endurance. PSV is ideal for use in the difficult-to-wean patient because it allows gradual application of spontaneous support to enhance respiratory strength and conditioning (Box 7-2).146 Enteral and parenteral nutrition should be adjusted to maintain the total caloric intake to no more than 10% above the estimated caloric needs of the patient. Excess calories will be converted to fat, with a high respiratory quotient and increased CO2 production. Nutritional support high in glucose will have a similar effect.150 Manipulation of feedings along with treatment of sepsis may reduce VCO2 and enhance weaning. Pulmonary edema should be treated with diuretics. Some patients will benefit from a tracheostomy to avoid ongoing upper airway contamination, to decrease dead space and airway resistance, and to provide airway access for evacuation of secretions during the weaning process. In addition, the issue of ‘extubating’ the patient is removed by tracheostomy. Spontaneous breathing trials, therefore, are easy to perform, and the transition from the mechanical ventilator is a much smoother and efficient process.151 In older patients, the tracheostomy can be performed percutaneously in the ICU.152 Long-term complications are fairly minimal in older patients. However, in newborns and infants, the rate of development of stenoses and granulation tissue may be significant.153,154

Nonconventional Modes and Adjuncts to Mechanical Ventilation

High-Frequency Ventilation

The concept of high-frequency jet ventilation (HFJV) was developed in the early 1970s to provide gas exchange during procedures performed on the trachea. HFJV uses small bursts of gas through a small ‘jet port’ in the endotracheal tube typically at a rate of 420 breaths/min, with the range being 240–660 breaths/min.155 The expiratory phase is passive.156 The Vt is adjusted by controlling the PIP, which is usually initiated at 90% of conventional PIP. CO2 removal is most affected by the ΔP. Therefore, an increase in the PIP or a decrease in the PEEP will result in enhanced CO2 elimination. Adjusting the Paw, PEEP, and FiO2 alters oxygenation. HFJV is typically superimposed on background conventional Vt mechanical ventilation.

The utilization of HFJV has decreased in favor of HFOV, which uses a piston pump-driven diaphragm and delivers small volumes at frequencies between 3–15 Hz.155 Both inspiration and expiration are active. Oxygenation is manipulated by adjusting Paw, which controls lung inflation similar to the role of PEEP in conventional mechanical ventilation. CO2 elimination is controlled by adjusting the tidal volume, also known as the amplitude or power. In short, only four variables are adjusted during HFOV:

1. Mean airway pressure (Paw) is typically initiated at a level 1–2 cmH2O higher in premature newborns and 2–4 cmH2O higher in term newborns and children than that used during conventional mechanical ventilation.156 For most disease processes, Paw is adjusted thereafter to maintain the right hemidiaphragm at the rib 8 to 9 level on the anteroposterior chest radiograph.

2. Frequency (Hz) is usually set at 12 Hz in premature newborns and 10 Hz in term patients. Lowering the frequency tends to result in an increase in Vt and a decrease in PaCO2.

3. Inspiratory time, which may be increased to enhance tidal volume, is usually set at 33%.

4. Amplitude or power (ΔP) is set to achieve good chest wall movement and adequate CO2 elimination.

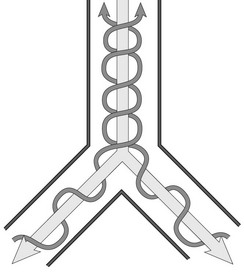

Gas exchange during HFOV is thought to occur by convection involving those alveoli located close to airways. For the remaining alveoli, gas exchange occurs by streaming, a phenomenon in which inspiratory gas, which has a parabolic profile, tends to flow down the center of the airways whereas the expiratory flow, which has a square profile, takes place at the periphery (Fig. 7-13).157 Other effects may also play a role: (1) pendelluft, in which gas exchange takes place between lung units with different time constants, as some are filling while others are emptying; (2) the movement of the heart itself may enhance mixing of gases in distal airways; (3) Taylor dispersion, in which convective flow and diffusion together function to enhance distribution of gas; and (4) local diffusion.158

FIGURE 7-13 Streaming as a mechanism of gas exchange during high-frequency ventilation. Note that the parabolic wavefront of the inspiratory gas induces central flow in the airways, whereas expiratory gas flows at the periphery.

HFOV should be applied to the newborn and child for whom conventional ventilation is failing, because of either parameters of oxygenation or CO2 elimination. The advantage of HFOV lies in the alveolar distention and recruitment that is provided while limiting exposure to potentially injurious high ventilator pressures.159 Thus, the approach during HFOV should be to apply a mean airway pressure that will effectively recruit alveoli and maintain oxygenation while limiting the ΔP to that which will provide chest wall movement and adequate CO2 elimination. CO2 elimination at lower PIPs may be a specific advantage in patients with air leak, especially those with bronchopleural fistulas.160 Once again, the effect on DO2, rather than simply PaO2, should be considered.

Although some studies with HFOV in preterm newborns have suggested that the incidence of BPD is similar to that found with conventional ventilation, other trials have found an increase in the rescue rate and a reduction in BPD with HFOV.161–165 One multicenter, randomized trial found that 56% of preterm newborns managed with HFOV were alive without the need for supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks postmenstrual age as compared with 47% of those receiving conventional ventilation (P = 0.046).166 In an additional pilot study, those preterm infants managed with HFOV were extubated earlier and had decreased supplemental oxygen requirements.167 In addition, improved neurodevelopmental outcomes were also seen after early intervention with HFOV, especially when used in conjunction with surfactant.168 Thus, although mixed, the data would suggest a reduction in pulmonary morbidity with the use of HFOV when compared with conventional ventilation.

In term newborns and children with respiratory insufficiency, studies suggest that the rescue rate and survival in those treated with HFOV is significantly increased when compared with conventional mechanical ventilation.169–171 In a randomized controlled trial of HFOV and inspired (inhaled) nitrous oxide (iNO) in pediatric ARDS, HFOV with or without iNO resulted in greater improvement in the PaO2/FiO2 ratio than did conventional mechanical ventilation.172 However, in contrast, one randomized controlled trial in term newborns failed to identify a significant difference in outcome between these treatment modalities.173 In fact, a Cochrane Database review of randomized clinical trials comparing the use of HFOV versus conventional ventilation failed to show any clear advantage in the elective use of HFOV as a primary modality in the treatment of premature infants with acute pulmonary dysfunction.174

Inhaled Nitric Oxide Administration

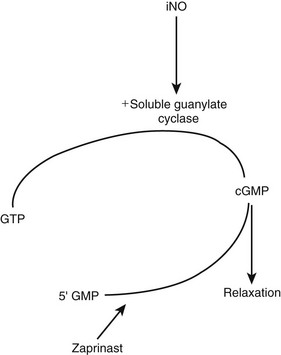

Nitric oxide is an endogenous mediator that serves to stimulate guanylate cyclase in the endothelial cell to produce cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which results in relaxation of vascular smooth muscle (Fig. 7-14).175 NO is rapidly scavenged by heme moieties. Therefore, iNO serves as a selective vasodilator of the pulmonary circulation, but is inactivated before reaching the systemic circulation. Diluted in nitrogen and then mixed with blended oxygen and air, iNO is administered in doses of 1–80 parts per million (ppm).

FIGURE 7-14 Mechanism of action of inhaled nitrous oxide (iNO) in inducing vascular smooth muscle relaxation. Zaprinast is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that may increase the potency and duration of the effect of iNO. GTP, guanosine triphosphate; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate. (Reprinted from Hirschl RB. Innovative therapies in the management of newborns with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg 1996;5:255–65.)

Pediatric patients with respiratory failure demonstrate increases in PaO2 with iNO at 20 ppm.176 Unfortunately, a prospective, randomized, controlled trial investigating the effects of iNO therapy in children with respiratory failure revealed that although pulmonary vascular resistance and systemic oxygenation were acutely improved at one hour by administration of 10 ppm iNO, a sustained improvement at 24 hours could not be identified.177

Other studies have shown more promising results with iNO. In one study, only 40% of the iNO-treated term infants with pulmonary hypertension required ECLS when compared with 71% of controls.178 These results were corroborated in another study by demonstrating a reduction in the need for ECLS in control newborns (ECLS, 64%) when compared with iNO-treated newborns (ECLS, 38%; P = 0.001).179 The incidence of chronic lung disease was also decreased in newborns managed with iNO (7% vs 20%). Similar results were noted for infants with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) who were on HFOV. In another study, the need for ECLS was decreased from 55% in the control HFOV group to 14% in the combined iNO and HFOV group (P = 0.007).180 In a clinical trial conducted by the Neonatal Inhaled Nitric Oxide Study (NINOS) Group, neonates born at 34 weeks or older gestational age with hypoxic respiratory failure were randomized to receive 20 ppm iNO or 100% oxygen as a control.181 If a complete response, defined as an increase in PaO2 of more than 20 mmHg within 30 minutes after gas initiation, was not observed, then iNO at 80 ppm was administered. Sixty-four per cent of the control group and 46% of the iNO group died within 120 days or were treated with ECLS (P = 0.006). No difference in death was found between the two groups (iNO, 14% vs control, 17%), but significantly fewer neonates in the iNO group required ECLS (39% vs 54%). Follow-up at age 18 to 24 months failed to demonstrate a difference in the incidence of cerebral palsy, rate of sensorineural hearing loss, and mental developmental index scores between the control and iNO patients.182 Other studies have similarly failed to identify a difference in pulmonary, neurologic, cognitive, or behavioral outcomes between survivors managed with iNO and those in the conventional group.183

An associated, but separate, trial demonstrated no difference in mortality and a significant increase in the need for ECLS when neonates with congenital disphragmatic hernia (CDH) were treated with 20 or 80 ppm of iNO versus 100% oxygen as control.184 It should be noted, however, that some investigators have suggested that the efficacy of iNO in patients with CDH may be more substantial after surfactant administration or at the point at which recurrent pulmonary hypertension occurs.185 iNO administration also may be helpful in the moribund CDH patient until ECLS can be initiated.

Some concern has been expressed for the development of intracranial hemorrhage in premature newborns treated with iNO. More than a 25% increase in the arterial/alveolar oxygen ratio (PaO2/PAO2) was observed in ten of 11 premature newborns, with a mean gestational age of 29.8 weeks and severe RDS, in response to administration of 1–20 ppm iNO.186 However, in seven of these 11 newborns, intracranial hemorrhage developed during their hospitalization. Also, a meta-analysis of the three completed studies evaluating the efficacy of iNO in premature newborns suggested no significant difference in survival, incidence of chronic lung disease, or rate of development of intracranial hemorrhage between iNO and controls.187

NO is associated with the production of potentially toxic metabolites. When combined with O2, iNO produces peroxynitrates, which can be damaging to epithelial cells and also can inhibit surfactant function.188,189 Nitrogen dioxide, which is toxic, can be produced, and hemoglobin can be oxidized to methemoglobin. Additional concerns exist about the immunosuppressive effects and the potential for platelet dysfunction.

Surfactant Replacement Therapy

The use of exogenous surfactant has been responsible for a 30–40% reduction in the odds of death among very low birth weight newborns with RDS.190,191 In addition, in those premature neonates with birth weight more than 1250 g, mortality in a controlled, randomized, blinded study decreased from 7% to 4%.192

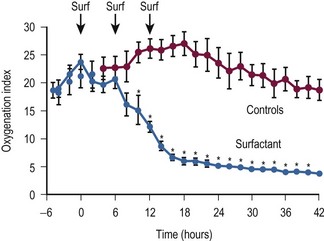

A randomized, prospective, controlled trial in term newborns with respiratory insufficiency demonstrated that the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was significantly reduced in those managed with surfactant when compared with placebo.193 The benefit of surfactant was greatest in those with a lower oxygenation index (<23). Another randomized controlled study demonstrated the utility of surfactant in term newborns with the meconium aspiration syndrome.194 The OI minimally decreased following the initial dose, but markedly decreased with the second and third surfactant doses from a baseline of 23.7 to 5.9 (Fig. 7-15). After three doses of surfactant, PPHN had resolved in all but one of the infants in the study group versus none in the control group. The incidence of air leaks and need for ECLS were markedly reduced in the surfactant group compared with the control infants. The neurodevelopmental outcome, however, was not affected by timing of surfactant administration. Therefore, gas exchange after intubation can be initially evaluated before surfactant is given, if needed.195 The incidence of air leaks, chronic lung disease, and time on the ventilator seem to improve though when early surfactant administration with extubation to nasal CPAP was used.196

FIGURE 7-15 The effect of exogenous surfactant administration on oxygen index in term newborns with meconium-aspiration syndrome. (Reprinted from Findlay RD, Taeusch HW, Walther FJ. Surfactant replacement therapy for meconium aspiration syndrome. Pediatrics 1996;97:48–52.)

Studies have concluded that surfactant phospholipid concentration, synthesis, and kinetics are not significantly deranged in infants with CDH compared with controls, although surfactant protein A concentrations may be reduced in CDH newborns on ECMO.197–199 Animal and human studies have suggested that surfactant administration before the first breath is associated with enhancement in PaO2 and pulmonary mechanics.200,201 However, among CDH patients on ECLS, no difference was noted in terms of lung compliance, time to extubation, period of oxygen requirement, and the total number of hospital days.197

In summary, multiple approaches to preserve lung function should be used in patients with severe lung injury or RDS, including limiting lung volumes, recruitment maneuvers, prone positioning, APRV, high-frequency oscillation, nitric oxide, surfactant, and early ECMO use in nonresponders.202,203

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), diagnosed at 48 hours or later on mechanical ventilation, is the second most common hospital-acquired infection in the neonatal and pediatric ICUs. Occurring in 3–10% of all ventilated PICU patients and up to 32% of NICU patients, VAP results in higher mean lengths of ICU stay, increased mortality rates, and increased hospital costs.204–206 Controversies surround the definition, treatment, and prevention of VAP. Finally, many studies do not incorporate the pediatric population and the data therefore cannot be applied blindly to all patients.