Measurement of bone mass

Bone mass, measured by bone mineral densitometry, is used to establish the diagnosis of osteoporosis, to predict the risk of subsequent fractures, and to monitor changes in bone mass during therapy for osteoporosis. No clinical finding, laboratory test, or other radiographic examination is able to reliably identify individuals with osteoporosis. Conventional radiographic techniques are not sensitive enough to diagnose osteoporosis as they do not reliably detect bone loss until 30% to 40% of bone mineral is lost. Although bone densitometry may determine low bone mass, it cannot identify the etiology of the bone loss. Thus, bone densitometry must be used with a complete clinical evaluation, laboratory testing, and other diagnostic studies to determine the cause of and the most appropriate treatment for osteoporosis.

2. Is bone mass the only parameter that determines whether a bone will fracture?

Although decreased bone mass is the primary determinant of whether a bone will fracture, bone architecture and geometry are also important factors contributing to bone strength. The relationship between bone mass and fracture risk is more powerful than the relationship between serum cholesterol concentration and coronary artery disease. A decrease in bone mass of one standard deviation (SD) doubles the risk of fracture. In comparison, a decrease in the cholesterol concentration of 1 SD increases the risk of coronary artery disease by only 20% to 30%.

3. How does bone densitometry measure bone mass?

All bone densitometry techniques determine the amount of calcium present in bone by utilizing an ionizing radiation source (either from a radionuclide or from an x-ray tube) and a radiation detector. Bone densitometry is based on the principle that bone absorbs radiation in proportion to its bone mineral content. The bone mineral content of the bone (or a region of interest within a bone) is then divided by the measured area. The result is the bone mineral density (BMD), expressed in grams per unit area (g/cm2). This BMD is not a true volumetric density (g/cm3) but rather an areal density. In this chapter, bone mass and BMD are used interchangeably.

4. What techniques are available to measure bone mass?

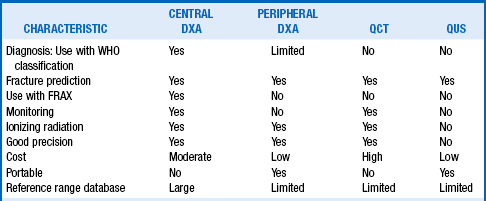

The techniques available to measure bone mass include dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and quantitative computed tomography (QCT). Central DXA measures bone mass of the hip, spine, and whole skeleton, whereas peripheral DXA measures bone mass of the forearm only. Another technique, quantitative ultrasound (QUS), transmits ultrasound waves through the bone. The more complex and denser the bone structure, the greater will be the attenuation of the ultrasound wave. Thus, QUS may determine both density and structure of the bone. Table 10-1 compares these bone mass measurement techniques.

5. What is the preferred method for measuring bone mass?

DXA is the preferred method for measuring bone mass. It has the best correlation with fracture risk, requires relatively short scanning times (< 5 minutes), determines bone mass in all areas of the skeleton with high accuracy and reproducibility (precision), and is associated with a small radiation exposure. DXA does not require replacement of the radiation source. Drawbacks of DXA are the cost of the equipment, exposure of patients to ionizing radiation (no matter how small a dose), and cost of the test (in comparison with some other methods).

6. What are the indications for the measurement of bone mass?

Widespread BMD screening for osteoporosis is not recommended at this time. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for osteoporosis of women of all racial and ethnic groups age 65 or greater and in women 50 to 65 years of age whose 10-year risk for any osteoporotic fracture is 9.3% or greater (determined by the FRAX fracture assessment tool; see later). The USPSTF concluded that for men, evidence of the benefits of screening for osteoporosis is lacking and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommends BMD testing for the following:

Women age 65 and older and men age 70 and older regardless of clinical risk factors

Women age 65 and older and men age 70 and older regardless of clinical risk factors

Younger postmenopausal women and men age 50 to 69 for whom there is concern about the patient’s clinical risk factor profile

Younger postmenopausal women and men age 50 to 69 for whom there is concern about the patient’s clinical risk factor profile

Women in the menopausal transition if there is a specific risk factor associated with increased fracture risk, such as low body weight, prior low-trauma fracture, or high-risk medication

Women in the menopausal transition if there is a specific risk factor associated with increased fracture risk, such as low body weight, prior low-trauma fracture, or high-risk medication

Adults who have a fracture after age 50

Adults who have a fracture after age 50

Adults who have a condition (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) or are taking a medication (e.g., glucocorticoids in a daily dose ≥ 5 mg prednisone or equivalent for ≥ 3 months) associated with low bone mass or bone loss

Adults who have a condition (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) or are taking a medication (e.g., glucocorticoids in a daily dose ≥ 5 mg prednisone or equivalent for ≥ 3 months) associated with low bone mass or bone loss

Anyone being considered for pharmacologic therapy for osteoporosis

Anyone being considered for pharmacologic therapy for osteoporosis

Anyone being treated for osteoporosis, to monitor treatment effect

Anyone being treated for osteoporosis, to monitor treatment effect

Anyone not receiving therapy in whom evidence of bone loss would lead to treatment

Anyone not receiving therapy in whom evidence of bone loss would lead to treatment

Postmenopausal women who are discontinuing estrogen should be considered for bone density testing.

In addition, DXA is also being increasingly used to study bone status in pediatric and adolescent patients, to perform vertebral fracture assessment, and to determine body composition.

7. What do bone mass measurements mean?

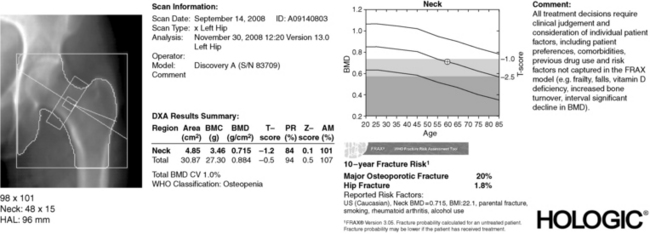

The bone densitometry report gives the absolute bone mass measurements (in g/cm2), which do not provide clinically useful information unless these values are compared with those of reference populations. To do this, the BMD report provides additional pieces of information: a T-score and a Z-score (Fig. 10-1).

The T-score is the number of SDs that the patient’s BMD is above or below the mean BMD of a normal young adult gender-matched population. This population represents the optimal or peak BMD for the patient. A patient whose BMD is 1 SD below that of the young reference population has a T-score of −1.0. At the spine, 1 SD represents about 10% of the bone mass. Thus, someone with a T-score of −1.0 has lost about 10% of his or her bone mass or has fallen short by 10% of achieving an optimal peak bone mass. Because the T-score is a good predictor of future fractures, it is used to diagnose osteoporosis.

9. What do Z-scores tell us about the patient?

The Z-score is the number of SDs that the patient’s BMD is above or below the mean BMD of an age- and gender-matched population. The Z-score compares a patient’s BMD with that of other individuals of the same age. A Z-score less than expected for a given individual (e.g., less than −2.0) indicates that the individual has lower BMD than is normal for his/her age. This finding should prompt a search for associated medical or lifestyle conditions (current or in the past) that may have accelerated bone loss or prevented the patient from reaching peak bone mass.

10. What are the diagnostic classifications for bone mass?

In 1994, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed criteria for the diagnosis of osteoporosis and osteopenia in postmenopausal white women and older men using T-scores calculated from DXA BMD measurements from the spine, hip, or forearm. A T-score greater than −1.0 defines normal BMD, a T-score between −1.0 and −2.5 defines low BMD (or osteopenia), and a T-score less than −2.5 defines osteoporosis. Established (or severe) osteoporosis is defined as a T-score less than −2.5 and the presence of one or more osteoporotic fractures.

11. How should the WHO criteria be used?

The WHO classification criteria were derived from data from white postmenopausal women. Thus, these definitions should be applied to other ethnic groups or to men with caution. The WHO criteria were not intended to apply to premenopausal women, men younger than 50 years, or children. Also, these criteria were developed from studies using DXA. Therefore, applying the WHO criteria to bone mass measurements obtained with other technologies (such as QCT and QUS) may be misleading. Finally, the WHO definitions for osteopenia and osteoporosis were developed as general guidelines for diagnosis and were not intended to require or restrict therapy for individual patients.

12. How are bone density measurements interpreted in men and non-Caucasians?

The criteria by which a densitometric diagnosis of osteoporosis can be made in males and in non-Caucasians is extremely controversial because it is unclear whether fractures occur at the same BMD values in men and non-Caucasians as in Caucasian women. Pending additional studies, the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) has recommended that osteoporosis in these groups be diagnosed at or below a T-score of −2.5 using a gender-adjusted but not a race-adjusted normative database. The database is programmed into the densitometer. The clinician needs to understand which database is being used to generate the T- and Z-scores.

13. Can bone densitometry determine vertebral fractures?

Vertebral fractures are the most common of all osteoporotic fractures, occurring in 15% of women 50 to 59 years of age and in 50% of women 85 years or older. The majority of these vertebral fractures are classified as mild, with a reduction in height of not more than 20% to 25%. They may be asymptomatic, often occur in the absence of specific trauma, and frequently do not come to clinical attention or are underreported when radiographic studies are performed. The presence of these mild fractures increases the risk of subsequent fractures. The image generated by routine spine DXA should not be used to diagnose vertebral fractures. Some DXA machines have a special program (Vertebral Fracture Assessment [VFA]) to image the thoracic and lumbar spine for the purpose of detecting these morphometric vertebral fracture deformities. The identification of a previously unrecognized vertebral fracture may change diagnostic classification, assessment of fracture risk, and treatment decisions. Appropriate candidates for VFA include postmenopausal women or men with low bone mass (osteopenia) and at least one risk factor (see the ISCD website for a list of specific risk factors for men and women), women or men receiving long-term glucocorticoid therapy (equivalent to 5 mg or more of prednisone daily for 3 months or longer), and postmenopausal women or men with osteoporosis, if documentation of one or more vertebral fractures will alter clinical management.

14. How is fracture risk determined?

The WHO has developed the FRAX fracture risk assessment tool to determine the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture and the 10-year probability of hip fracture in men and women. This tool utilizes clinical risk factors and BMD at the femoral neck (or total hip BMD) when available. Treatment guidelines that rely exclusively or predominantly on a densitometric diagnosis of osteoporosis to select patients for treatment will miss many patients with T-scores greater than −2.5 who are at high risk for fracture and might benefit from pharmacologic therapy. Therefore, it is recommended that this tool be used for untreated postmenopausal women or men older than 50 years who have T-scores between −1.0 and −2.5, with no history of hip or vertebral fracture, and with a DXA-evaluable hip. The FRAX assessment tool is available at www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX and should be available soon on newer DXA scanners.

FRAX is intended for determining fracture risk for postmenopausal women and men age 50 and older. It should not be used in younger adults or children. The tool has not been validated in patients currently or previously treated with medications for osteoporosis. In such patients, clinical judgment must be exercised in interpreting FRAX scores. In the absence of femoral neck BMD, total hip BMD may be substituted. However, use of BMD from non-hip sites in the algorithm is not recommended because such use has not been validated.

15. Discuss how bone mass measurements are used to determine the need for treatment of osteoporosis.

The health-care provider should use information from bone mass testing in conjunction with knowledge of a patient’s specific medical and personal history to determine the most appropriate treatment. BMD results should not be used as the sole determinant for treatment decisions. The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends treatment of postmenopausal women and men age 50 and older with all of the following features:

A hip or vertebral (clinical or morphometric) fracture

A hip or vertebral (clinical or morphometric) fracture

A T-score ≤ −2.5 at the femoral neck or spine after appropriate evaluation to exclude secondary causes

A T-score ≤ −2.5 at the femoral neck or spine after appropriate evaluation to exclude secondary causes

Low bone mass (T-score between −1.0 and −2.5 at the femoral neck or spine) and a 10-year probability of a hip fracture ≥ 3% or a 10-year probability of a major osteoporosis-related fracture ≥ 20% based on the U.S.-adapted FRAX assessment tool

Low bone mass (T-score between −1.0 and −2.5 at the femoral neck or spine) and a 10-year probability of a hip fracture ≥ 3% or a 10-year probability of a major osteoporosis-related fracture ≥ 20% based on the U.S.-adapted FRAX assessment tool

Clinicians should use clinical judgment to treat patients at lower FRAX risk levels if additional risk factors are present.

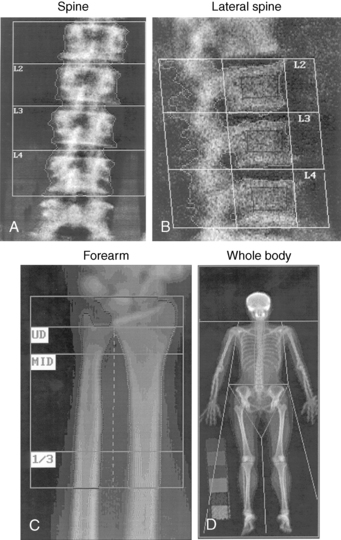

16. Which bone(s) should be selected for measurement of bone mass?

It is possible to measure bone mass at several sites (Fig. 10-2). Measurement of bone mass at any skeletal site has value in predicting fracture risk. However, the bone density of the hip is the best predictor of hip fractures (the osteoporotic fracture with the greatest mortality and morbidity). The bone mass of the hip also predicts fractures at other sites, as well as do bone mass measurements at those sites. Hip bone mass measurements are the only ones used by the FRAX assessment tool. For these reasons, the hip is the preferred site for measurement. Although there is significant concordance between skeletal sites in predicting bone mass, there is still enough discordance in bone mass at various sites that single bone mass measurements should not be relied on to diagnose osteoporosis. Thus, bone mass should be measured at both the hip and the spine, and the diagnosis of osteoporosis should be based on the lowest T-score.

Figure 10-2. Images of several skeletal sites scanned by a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry bone densitometer. (See Figure 10-1 for image of the hip.)

17. What is the role of bone mass measurements of the forearm?

Measurement of peripheral bone mass (e.g., the forearm) generally adds little to the evaluation of an individual with postmenopausal osteoporosis. However, the forearm appears to be the best site to assess the effects on bone of excess parathyroid hormone associated with primary hyperparathyroidism. In addition, measurement of forearm bone mass should be performed when the hip and spine cannot be accurately measured or when a patient is over the weight limit for the DXA table. The weight limit for most DXA machines is 300 pounds, although some newer machines can measure bone density in people who weigh up to 400 pounds. Peripheral bone mass measurements have not been shown to be useful for monitoring the effects of therapy for osteoporosis because changes in bone density occur very slowly at this site.

18. How often should bone mass measurements be repeated?

The frequency of bone density measurements is determined, in part, by the precision error (or reproducibility) of the technique. The precision of BMD measurements by DXA is approximately 1.0% for spine and 1% to 2% for the femoral neck. This means that the smallest difference between two BMD measurements that is significant is a change of 2.83% at the spine and 5.66% at the femoral neck. In contrast, the average amount of early postmenopausal bone loss from the spine is 1% to 2% per year. Therefore, to obtain statistically meaningful BMD results, postmenopausal women should not undergo routine DXA measurements of the spine more often than once every 2 years unless accelerated bone loss is suspected. Measurement of BMD every 6 months is recommended for patients in whom glucocorticoid therapy is being initiated for this reason. One study has indicated that the interval for repeat BMD measurements to screen for osteoporosis may be considerably longer than 2 years for older women with normal or near-normal bone mass on initial screening.

19. What conditions limit the accuracy of bone mass measurements?

Degenerative changes, oral contrast agents used for other radiographic studies, and osteophytes all falsely elevate the measured spine bone density. Anatomic distortions such as lumbar disc disease, compression fractures, scoliosis, prior surgical intervention, and vascular calcifications in the overlying aorta also affect the accuracy of spine measurements. Likewise, previous surgery on the hip may alter bone mass at this site.

20. Interpret the BMD results from the four patients whose BMD scores are shown in the table. Each patient is a white postmenopausal woman.

| Patient 1 | T-score = −0.9 | Z-score = +0.2 |

| Patient 2 | T-score = −2.0 | Z-score = −0.9 |

| Patient 3 | T-score = −3.0 | Z-score = −1.4 |

| Patient 4 | T-score = −3.0 | Z-score = −2.5 |

Patient 1 has a normal bone mass.

Patient 1 has a normal bone mass.

Patient 2 has a low bone mass (osteopenia) that is appropriate for her age because her Z-score is greater than −2.0.

Patient 2 has a low bone mass (osteopenia) that is appropriate for her age because her Z-score is greater than −2.0.

Patient 3 has osteoporosis, and this bone loss is appropriate for her age.

Patient 3 has osteoporosis, and this bone loss is appropriate for her age.

Patient 4 has osteoporosis with bone loss that is greater than expected for her age. This bone density finding should prompt a thorough evaluation to rule out secondary causes of osteoporosis (such as hyperthyroidism, malabsorption, Cushing’s syndrome, hypogonadism, vitamin D deficiency, excessive alcohol consumption, celiac disease, and use of certain drugs).

Patient 4 has osteoporosis with bone loss that is greater than expected for her age. This bone density finding should prompt a thorough evaluation to rule out secondary causes of osteoporosis (such as hyperthyroidism, malabsorption, Cushing’s syndrome, hypogonadism, vitamin D deficiency, excessive alcohol consumption, celiac disease, and use of certain drugs).

Binkley, N, Schmeer, P, Wasnich, R, et al. What are the criteria by which a densitometric diagnosis of osteoporosis can be made in males and noncaucasians. (Suppl). J Clin Densitom. 2002;5:S19.

Binkovitz, LA, Sparke, P, Henwood, MJ, Pediatric DXA. clinical applications. Pediatr Radiol 2007;37:625.

Blake, G, Fogelman, I. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry and its clinical applications. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2002;6:207.

Blake, GM, Fogelman, I. The clinical role of dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71:406.

Cummings, SR, Bates, D, Black, D, Clinical use of bone densitometry. scientific review. JAMA 2002;288:1889.

Dasher, LG, Newton, CD, Lenchik, L. Dual x-ray absorptiometry in today’s clinical practice. Radiol Clin N Am. 2010;48:541.

Diacinti, D, Guglielmi, G. Vertebral morphometry. Radiol Clin N Am. 2010;48:561.

Gourlay, ML, Fine, JP, Preisser, JS, et al. Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med. 2012;364:248.

Hamdy, R, Petak, S, Lenchik, L. Which central dual x-ray absorptiometry skeletal sites and regions of interest should be used to determine the diagnosis of osteoporosis. (Suppl). J Clin Densitrom. 2002;5:S11.

Kanis, JA, Hans, D, Cooper, C. Interpretation and use of FRAX in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2395.

Lenchik, L, Kiebzak, G, Blunt, B. What is the role of serial bone mineral density measurements in patient management. (Suppl). J Clin Densitom. 2002;5:S29.

Lewiecki, EM. Bone densitometry and vertebral fracture assessment. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2010;8:123.

Lewiecki, EM, Laster, AJ. Clinical applications of vertebral fracture assessment by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4215.

Miller, P. Bone mineral density—clinical use and application. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32:159.

Miller, PD, Leonard, MB. Clinical use of bone mass measurements in adults for the assessment and management of osteoporosis. In: Favus MJ, ed. Primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. New York: Raven Press; 2006:150.

Miller, PD, Zapalowski, C, Kulak, CA, et al, Bone densitometry. the best way to detect osteoporosis and to monitor therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:1867.

Shagam, J, Bone densitometry. an update. Radiol Technol 2003;74:321.

Siris, ES, Baim, S, Nattiv, A, Primary care use of FRAX®. absolute fracture risk assessment in postmenopausal women and older men. Postgrad Med 2010;122:82.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Screening for Osteoporosis. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:356.

, WHO Study Group. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis, WHO Tech Rep Ser 843, 1994 Geneva: World Health Organization;.