Chapter 238 Measles

Epidemiology

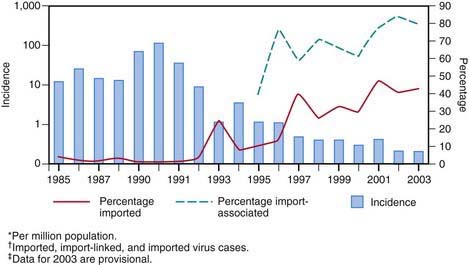

Measles continues to be imported into the USA from abroad; therefore, continued maintenance of >90% immunity through vaccination is necessary to prevent widespread outbreaks from occurring (Fig. 238-1).

Clinical Manifestations

Measles is a serious infection characterized by high fever, an enanthem, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and a prominent exanthem. After an incubation period of 8-12 days, the prodromal phase begins with a mild fever followed by the onset of conjunctivitis with photophobia, coryza, a prominent cough, and increasing fever. Koplik spots represent the enanthem and are the pathognomonic sign of measles, appearing 1 to 4 days prior to the onset of the rash (Fig. 238-2). They first appear as discrete red lesions with bluish white spots in the center on the inner aspects of the cheeks at the level of the premolars. They may spread to involve the lips, hard palate, and gingiva. They also may occur in conjunctival folds and in the vaginal mucosa. Koplik spots have been reported in 50-70% of measles cases but probably occur in the great majority.

Figure 238-2 Koplik spots on the buccal mucosa during the 3rd day of rash.

(From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Public health image library, image #4500 [website]. http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/details.asp.)

Symptoms increase in intensity for 2-4 days until the 1st day of the rash. The rash begins on the forehead (around the hairline), behind the ears, and on the upper neck as a red maculopapular eruption. It then spreads downward to the torso and extremities, reaching the palms and soles in up to 50% of cases. The exanthem frequently becomes confluent on the face and upper trunk (Fig. 238-3).

Differential Diagnosis

Typical measles is unlikely to be confused with other illnesses, especially if Koplik spots are observed. Measles in the later stages or inapparent or subclinical infections may be confused with a number of other exanthematous immune-mediated illnesses and infections, including rubella, adenoviruses, enteroviruses, and Epstein-Barr virus. Exanthem subitum (in infants) and erythema infectiosum (in older children) may also be confused with measles. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and group A streptococcus may also produce rashes similar to that of measles. Kawasaki syndrome can cause many of the same findings as measles but lacks discrete intraoral lesions (Koplik spots) and a severe prodromal cough, and typically leads to elevations of neutrophils and acute-phase reactants. In addition, the characteristic thrombocytosis of Kawasaki syndrome is absent in measles (Chapter 160). Drug eruptions may occasionally be mistaken for measles.

Complications

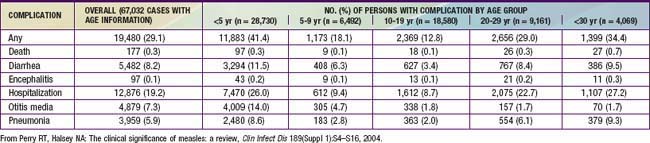

Complications of measles are largely attributable to the pathogenic effects of the virus on the respiratory tract and immune system (Table 238-1). Several factors make complications more likely. Morbidity and mortality from measles are greatest in patients <5 yr of age (especially <1 yr of age) and >20 yr of age. In developing countries, higher case fatality rates have been associated with crowding, which are possibly attributable to larger inoculum doses after household exposure. Severe malnutrition in children results in suboptimal immune response and higher morbidity and mortality with measles infection. Low serum retinol levels in children with measles have been shown to be associated with higher measles morbidity and mortality in developing countries and in the USA. Measles infection lowers serum retinol concentrations, so subclinical cases of hyporetinolemia may be made symptomatic during measles. Measles infection in immunocompromised persons is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Among patients with malignancy in whom measles develops, pneumonitis occurs in 58% and encephalitis in 20%.

Treatment

Vitamin A

Vitamin A deficiency in children in developing countries has long been known to be associated with increased mortality from a variety of infectious diseases, including measles. In the USA, studies in the early 1990s documented that 22-72% of children with measles had low retinol levels. In addition, one study demonstrated an inverse correlation between the level of retinol and severity of illness. Several randomized controlled trials of vitamin A therapy in the developing world and the USA have demonstrated reduced morbidity and mortality from measles. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests vitamin A therapy for selected patients with measles (Table 238-2).

Table 238-2 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR VITAMIN A TREATMENT OF CHILDREN WITH MEASLES

INDICATIONS

Children 6 mo-2 yr of age hospitalized with measles and its complications (e.g., croup, pneumonia, and diarrhea). (Limited data are available about the safety of and need for vitamin A supplementation for infants <6 mo of age).

Children >6 mo of age with measles who are not already receiving vitamin A supplementation and who have any of the following risk factors:

REGIMEN

Parenteral and oral formulations of vitamin A are available in the USA. The recommended dosage, administered as a capsule, is:

The dose should be repeated the next day and again 4 wk later for children with ophthalmologic evidence of vitamin A deficiency

Data from the American Academy of Pediatrics: Red book: 2009 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 28, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics, p 446.

Prevention

Vaccine

Measles vaccine in the USA is available as a monovalent preparation or combined with the rubella (MR) or measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, the last of which is the recommended form in most circumstances (Table 238-3). Following the measles resurgence of 1989-1991, a second dose of measles vaccine was added to the schedule. The current recommendations include a first dose at 12-15 mo followed by a second dose at 4-6 yr of age. Seroconversion is slightly lower in children who receive the first dose before or at 12 mo of age (87% at 9 mo, 95% at 12 mo, and 98% at 15 mo) because of persisting maternal antibody. For children who have not received 2 doses by 11-12 yr of age, a second dose should be provided. Infants who receive a dose before 12 mo of age should be given 2 additional doses at 12-15 mo and 4-6 yr of age.

| CATEGORY | RECOMMENDATIONS |

|---|---|

| Unimmunized, no history of measles (12-15 mo of age) | A 2-dose schedule (with MMR) is recommended The first dose is recommended at 12-15 mo of age; the 2nd is recommended at 4-6 yr of age |

| Children 6-11 mo of age in epidemic situations or prior to international travel | Immunize (with monovalent measles vaccine, or if not available, MMR); reimmunization (with MMR) at 12-15 mo of age is necessary, and a 3rd dose is indicated at 4-6 yr of age |

| Children 4-12 yr of age who have received 1 dose of measles vaccine at ≥12 mo of age | Reimmunize (1 dose) |

| Students in college and other post–high school institutions who have received 1 dose of measles vaccine at ≥12 mo of age | Reimmunize (1 dose) |

| History of immunization before the 1st birthday | Consider susceptible and immunize (2 doses) |

| History of receipt of inactivated measles vaccine or unknown type of vaccine, 1963-1967 | Consider susceptible and immunize (2 doses) |

| Further attenuated or unknown vaccine given with IG | Consider susceptible and immunize (2 doses) |

| Allergy to eggs | Immunize; no reactions likely |

| Neomycin allergy, nonanaphylactic | Immunize; no reactions likely |

| Severe hypersensitivity (anaphylaxis) to neomycin or gelatin | Avoid immunization |

| Tuberculosis | Immunize; if patient has untreated tuberculosis disease, start antituberculosis therapy before immunizing |

| Measles exposure | Immunize and/or give IG, depending on circumstances |

| HIV-infected | Immunize (2 doses) unless severely immunocompromised |

| Personal or family history of seizures | Immunize; advise parents of slightly increased risk of seizures |

| IG or blood recipient | Immunize at the appropriate interval (see Table 238-4) |

IG, immunoglobulin; MMR, measles-mumps-rubella vaccine.

From American Academy of Pediatrics: Red book: 2009 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 28, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics, p 450.

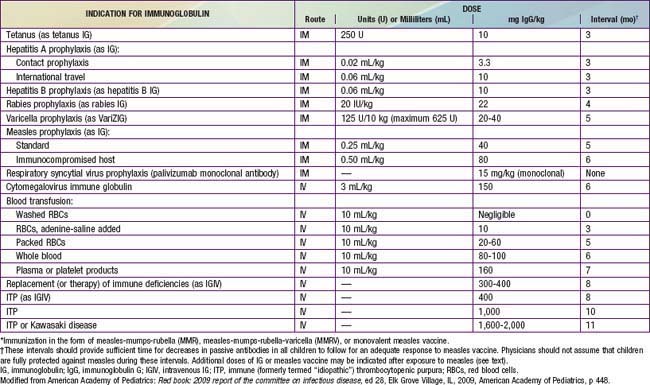

Passively administered immune globulin may inhibit the immune response to live measles vaccine, and administration should be delayed for variable amounts of time based on the dose of immune globulin (Table 238-4).

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Vitamin A treatment of measles. Pediatrics. 1993;91:1014-1015.

Asaria P, MacMahon E. Measles in the United Kingdom: can we eradicate it by 2010? BMJ. 2006;333:890-895.

Campbell H, Andrews N, Brown KE, et al. Review of the effect of measles vaccination on the epidemiology of SSPE. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:1334-1348.

Caulfield LE, deOvis M, Blössner M, et al. Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria and measles. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:193-198.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global measles mortality, 200–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1321-1326.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles—United States, January 1–April 25, 2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:494-498.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Out break of measles—San Diego, California, January–February 2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:203-206.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multistate measles outbreak associated with an international youth sporting event—Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Texas, August–September 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:169-172.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Import-associated measles outbreak—Indiana, May–June 2005. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:1073-1075.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: Measles—United States, January–July 2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:893-896.

Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Rivetti A, et al: Vaccines for measles, mumps, and rubella in children (review), Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD004407, 2005.

Dyken PR. Nonprogressive disease of post-infectious origin: a review of resurging subacute sclerosing parencephalitis (SSPE). Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001;7:217-225.

Elliman D, Bedford H. Achieving the goal for global measles mortality. Lancet. 2007;369:165-166.

Halsey NA. Measles in developing countries. BMJ. 2006;333:1234.

Katz SL. Has the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine been fully exonerated? Pediatrics. 2006;118:1744-1745.

Kremer JR, Muller CP. Measles in Europe—there is room for improvement? Lancet. 2009;373:356-358.

Meissner HC, Strebel PM, Orenstein WA. Measles vaccine and the potential for worldwide eradication of measles. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1065-1069.

Otten M, Kezaala R, Fall A, et al. Public-health impact of accelerated measles control in the WHO African region 2000–03. Lancet. 2005;366:832-838.

Parker AA, Staggs W, Dayan GH, et al. Implications of a 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana for sustained elimination of measles in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:447-454.

Perry RT, Halsey NA. The clinical significance of measles: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;189(Suppl 1):S4-S16.

Rosales FJ. Vitamin A supplementation of vitamin deficient measles patients lowers risk of measles-related pneumonia in Zambian children. J Nutr. 2002;132:3700-3703.

Redd SC, King GE, Heath JL, et al. Comparison of vaccination with measles-mumps-rubella vaccine at 9, 12, and 15 months of age. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(Suppl 1):S116-S122.

Remington PL, Hall WN, Davis IH, et al. Airborne transmission of measles in a physician’s office. JAMA. 1985;253:1574-1577.

Rivera ME, Mason WH, Ross LA, et al. Nosocomial measles infection in a pediatric hospital during a community-wide epidemic. J Pediatr. 1991;119:183-186.

Sugerman DE, Barskey AE, Delea MG, et al. Measles outbreak in a highly vaccinated population, San Diego, 2008: role of the intentionally under vaccinated. Pediatrics. 2010;125:747-755.

Suringa DWR, Bank LJ, Ackerman AB. Role of measles virus in skin lesions and Koplik’s spots. N Engl J Med. 1970;283:1139-1142.