30 Maxillofacial Disorders

• Temporomandibular joint dislocation is usually readily reduced in the emergency department after the patient has been pretreated with analgesic and antispasmodic agents.

• Epistaxis may be the initial complaint of a patient with a more serious systemic illness, such as a clotting disorder.

• When visible blood loss from the nasopharynx has been stopped, the clinician should examine the posterior oropharynx for ongoing occult blood loss.

• Posterior epistaxis accounts for about 10% of nasal hemorrhages and can result in large volumes of blood loss.

• Any abnormal neurologic or ocular physical findings in a patient with rhinosinusitis mandate further investigation to assess for central nervous system extension of the disease.

Temporomandibular Disorders

Epidemiology

The temporomandibular articulations are unique within the body in that they are bilateral joints that are nearly continuously in use. Consequently, the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is subject to both pain and dislocation. Discomfort of the TMJ was previously referred to as TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome. However, because it was realized that more than just the actual joint can be the source of a patient’s discomfort, the term has evolved to temporomandibular disorder (TMD). TMD is defined as craniofacial pain that involves the TMJ, masticatory muscles, and associated head and neck musculoskeletal structures.1 It is roughly estimated that more than 10 million people in the United States alone have symptomatic TMD.2 Most of those affected are women.

TMJ dislocation is an uncommon disorder, with one case series reporting 37 occurrences in 700,000 patient visits.3

Pathophysiology

TMD is probably due to excessive strain on the muscles of mastication with resultant strain on the capsular ligaments of the TMJ.4 The result is that the mandibular condyle does not articulate properly in its joint. The patient feels pain and senses an occlusal disturbance.

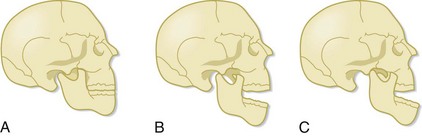

Patients with TMJ dislocation are unable to close their mouth. With normal function, when the mandible is open, the mandibular condyle moves anteriorly and inferiorly. When the mandible closes, the condyle moves posteriorly and superiorly and returns to its original location (Fig. 30.1). TMJ dislocation results when the mandibular condyle moves anterior to the temporal eminence (the anterior portion of the mandibular fossa) (see Fig. 30.1). Once the dislocation occurs, the muscles of mastication spasm, which results in trismus and inability of the patient to return the mandibular condyle to its anatomic position. The dislocation usually results from excessive opening of the mouth, such as occurs with yawning or laughing. TMJ dislocation can also be the result of trauma, seizure, or dystonic drug reactions.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Unilateral pain in the region of the TMJ and clicking or crepitance that is exacerbated by chewing are the classic complaints of a patient with TMD (Box 30.1). The dull or throbbing pain is localized to the preauricular region or to the muscles of mastication and typically worsens with movement of the mandible, such as when eating or talking. Pain may be most severe in the morning if bruxism is an issue.5 If a click is present, the patient hears it when jaw opening is initiated. The pain may also radiate to the neck, ears, mandible, or temporal region.

An inability to close the mouth following extreme jaw opening, such as yawning, is the classic manifestation of TMJ dislocation. If the dislocation is unilateral, the mandible will deviate away from the side of the dislocation (Box 30.2).

Treatment

Temporomandibular Disorders

Pain should be addressed with antiinflammatory agents (e.g., ibuprofen, 600 mg by mouth every 6 hours, or naproxen, 500 mg by mouth every 12 hours) and narcotic pain medications (e.g., oxycodone, 5 to 10 mg by mouth every 6 hours as needed). Warm compresses should also be applied to the TMJ region for 15 minutes three times per day. Benzodiazepines are used to relieve masseter muscle spasm (e.g., diazepam, 5 mg by mouth every 8 hours as needed). Behavioral modifications include minimizing masseter muscle use through a soft diet and cessation of gum chewing. Reassurance is important because up to 40% of patients will experience resolution of their TMD symptoms with little or no treatment (Box 30.3).6

If bruxism is suspected, dental follow-up should be arranged, and a bite appliance can be considered. To date, experimentation with the use of botulinum toxin to reduce masseter muscle contractility and strength has yielded mixed results.7

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Temporomandibular Disorders

Take antiinflammatory and pain medications as prescribed.

Apply warm compresses in front of your ear for 15 minutes 3 times per day.

Benzodiazepines may have been prescribed to control muscle spasm. These drugs may cause sedation.

Eat only soft foods until the symptoms resolve.

See your dentist for follow-up to evaluate whether bruxism is the cause of your condition.

Many cases resolve spontaneously and very few require aggressive treatment.

See your doctor or return to the emergency department if your pain is not controlled or if you are unable to fully open or close your mouth, which may indicate a dislocation of your jaw.

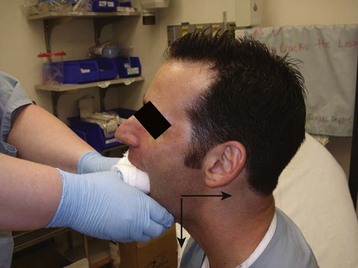

Temporomandibular Dislocation

Once the patient is comfortable, the clinician faces the patient and grasps the mandible inferiorly with the fingers of both hands. The clinician’s thumbs should be heavily wrapped in gauze for protection and then placed on the occlusive surfaces of the mandibular molars. Downward pressure is applied to move the mandibular condyle inferior to the temporal eminence. The mandible is then pushed posteriorly (Fig. 30.2). Once the condyle is posterior to the temporal eminence and pressure is released, the condyle returns to its anatomic position in the mandibular fossa. At the time of reduction, the masseter muscles may contract forcefully and cause the patient to inadvertently clench the jaw. The clinician must be aware of this possibility and ensure that the thumbs are guarded during the procedure and remove the thumbs from the occlusive surface of the molars as quickly as possible. If this method does not work, both thumbs may be placed simultaneously on the dislocated side and the reduction reattempted.8

In an effort to minimize risk to the practitioner, an extraoral approach to TMJ reduction was proposed by Chen et al. in 2007.9 The physician faces the patient and places a thumb on the palpable coronoid process that is displaced anteriorly. The fingers of that hand are placed on the mastoid process for stability. On the nondislocated side, the thumb is placed on the zygoma and the fingers hold the mandible angle. The nondisplaced side of the mandible is pulled anteriorly while concomitant pressure is applied posteriorly to the displaced coronoid process. Although this approach is less successful than the traditional approach, there is no risk of injury to the practitioner.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation

Avoid excessive mouth opening, including laughing and yawning, to prevent recurrence of the dislocation.

Take pain medications and muscle relaxants as prescribed. These drugs may cause sedation.

Follow up with an oromaxillofacial surgeon within 2 weeks.

Return to the emergency department if your pain is not controlled or if you are unable to fully close your mouth, which may indicate a recurrent dislocation.

Epistaxis

Epidemiology

The incidence of epistaxis is unknown, but it is estimated to occur in up to 60% of all individuals. The vast majority of these episodes are self-limited and only 6% require medical attention.10 Epistaxis affects both adults and children, with a higher incidence in children younger than 10 years and adults older than 35 years.11

Pathophysiology

The nasal mucosa is a highly vascular area, and any disruption of the mucosa can result in bleeding. Although epistaxis can be caused by trauma, this is not the most common cause. Bleeding more commonly results from upper respiratory infections (URIs), a dry environment, nasal foreign bodies, allergic rhinitis, nasal mucormycosis, topical nasal medications (including antihistamines and corticosteroids), and drugs taken intranasally such as cocaine (Box 30.4). Additionally, epistaxis may be the initial symptom of a primary or secondary systemic bleeding disorder. One study found that 45% of patients with bleeding severe enough to warrant hospitalization had an associated systemic disorder that may have contributed to the epistaxis.12

Box 30.4 Risk Factors for Epistaxis

The relationship of hypertension to epistaxis is controversial. It is unclear whether elevated blood pressure is the cause or the effect of epistaxis; therefore, hypertension alone is not known to be an independent risk factor for nasal hemorrhage.13–15

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Obtaining a detailed history is often the key to determining the cause of the patient’s epistaxis. The clinician must know whether the patient has recurrent epistaxis, easy bruising, or other sources of bleeding, such as when shaving or brushing the teeth, or is taking a platelet inhibitor or anticoagulant medication. The past medical history is important in a patient who has hepatic disease, atherosclerosis, Osler-Weber-Rendu disease (hemorrhagic telangiectasia), diabetes mellitus, or cancer with ongoing chemotherapy treatment because each of these conditions is a risk factor for epistaxis.16 Women are more prone to epistaxis during pregnancy.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Mechanical causes of epistaxis, such as trauma, nose picking, nasal foreign bodies, and nasogastric or nasotracheal intubation, directly disrupt the nasal mucosa. Blood dyscrasias, hepatic disease, platelet inhibitors, and anticoagulant medications result in decreased blood clotting and predispose the host to bleeding. Infectious causes include sinusitis, rhinitis, mucormycosis, and URIs that result in nasal congestion and vasodilation.16 In women, both endometriosis and pregnancy must be considered as causes of epistaxis. Environmental factors also play a role in the incidence of epistaxis. Visits to the ED for the treatment of epistaxis are more common in the winter months.11 This has been proposed to be due to lower ambient humidity and subsequent drying of the nasal membranes during the winter season. Barotrauma can also incite epistaxis.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Epistaxis

Epistaxis may be the initial manifestation of a primary or secondary blood dyscrasia.

Occluded nares may mask ongoing bleeding.

Hematemesis may be the initial complaint in patients with large-volume bleeding.

An antihypertensive agent (i.e., beta-blocker) can mask the early stages of hemorrhagic shock by limiting tachycardia.

Treatment

In the absence of massive epistaxis, the initial step is to evacuate intranasal clots and apply a topical vasoconstrictor and analgesic to the mucosa (Box 30.5). This can be achieved by soaking cotton pledgets in a combined vasoconstrictor and topical analgesic solution. If cotton is not available, rolled 2- × 2-inch gauze can be used. The analgesic is added to improve patient comfort during any necessary interventions once vasoconstriction has occurred. These medications are left in contact with the mucosa for 5 to 10 minutes.

If neither of the preceding measures is successful, direct compression of the mucosa through packing the anterior nasal cavity is necessary. This can be accomplished with nonadherent ribbon gauze packing or a nasal tampon or balloon. Preformed nasal tampons and nasal balloons are now widely available and are easily inserted. The tampon or balloon is lubricated with a water-based lubricant and then directed posteriorly into the nasal cavity. The tampon should be placed gently but firmly and quickly into the nasal cavity. If it is inserted too slowly, the first part may expand from contact with blood before insertion is complete, which makes further insertion more difficult for both the patient and clinician. If after insertion the tampon is not fully expanded, saline or a vasoconstrictive agent (see Box 30.5) can be dripped into the nasal cavity until expansion is achieved. If a balloon is used, it will need to be inflated with saline or air, depending on the model used. If nonadherent ribbon gauze is to be used instead, the technique is to insert the packing in an accordion pattern from posterior to anterior and inferior to superior. If the septum bows to the contralateral side after packing, packing the other side may be necessary. Pain medication may be needed to alleviate the discomfort from nasal packing. The packing should remain in place for 1 to 3 days.

Bleeding from posterior epistaxis is more challenging to control. By definition, the bleeding site is not readily visualized, thus making compression and treatment more difficult. The most rapid method for controlling posterior epistaxis is insertion of a posterior balloon device. Typically, this device has a double-balloon design, one balloon to tamponade the posterior nasal cavity and the other for the anterior nasal cavity. After the device is lubricated, it is inserted into the nasal cavity to its hub. The posterior balloon is inflated and the hub is then drawn out away from the nose until resistance is met. Resistance indicates that the posterior balloon has set in the posterior nasal cavity and is not in the pharynx. Next, the anterior balloon is inflated. The quantity of saline required to fill each balloon varies by device but is typically 7 to 10 mL for the posterior balloon and 15 to 30 mL for the anterior balloon.16

Laboratory tests have a limited role in patients with epistaxis. Patients with low- or moderate-volume anterior bleeding who have no known blood dyscrasia and who are not taking anticoagulant medications do not require any laboratory studies.12

If, however, the patient’s history or physical examination raises concern for a systemic cause of the epistaxis, studies should be ordered as appropriate for the clinician’s specific suspicions. Such studies may include a prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, coagulation factor levels, bleeding time, vitamin K level, and liver function tests.16 In patients exhibiting signs of shock, the hematocrit should be checked to obtain a starting value with which to compare serial measurements. Additionally, blood typing and screening may be necessary for a possible transfusion.

Otorhinolaryngologic consultation is not routinely necessary and should be reserved for refractory epistaxis, for which endoscopy for direct visualization and cauterization, surgical vessel ligation, or embolization may be necessary.11

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Epistaxis

Avoid nose blowing, bending over, and straining.

Be sure to open your mouth when you sneeze.

Avoid any activity that puts you at risk for nasal injury.

Use humidifiers and saline nasal spray to help keep the interior of your nose moist.

Take pain medications as needed.

Do not take aspirin or aspirin products.

Follow up with an otorhinolaryngologist in 24 to 72 hours.

Take your antibiotics as prescribed. It is important that you continue to take antibiotics as long as your nasal packing or balloon is in place.

Do not put anything into your nose.

If bleeding recurs, compress your nose by squeezing the bottom half of it with your thumb and index finger. Hold this compression for 10 minutes. If bleeding continues beyond this time, see your doctor or return to the emergency department.

See your doctor or return to the emergency department if a fever or rash develops.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Epistaxis

Apply a topical vasoconstrictive agent to the nasal mucosa.

Examine the nasopharynx and the posterior oropharynx to localize the source of bleeding.

Chemical cautery should be used with caution and bilateral septal cautery should be avoided to minimize the risk for septal injury.

Ensure that a posterior nasal balloon is properly secured to avoid airway occlusion.

Follow-Up and next Steps in Care

Patients with nasal packing or balloons should be treated with antistaphylococcal antibiotics to minimize the risk for sinusitis and toxic shock syndrome.17 Drug choices include amoxicillin–clavulanate potassium, 875 mg two times per day, and cephalexin, 500 mg four times per day. The packing should be left in place for 1 to 3 days and antibiotics continued until the packing is removed. Nasal packing containing antibiotics is also available; these products have been shown to inhibit the growth of nasal flora and may supplant the need for additional systemic antibiotics.

Sinusitis

Epidemiology

Sinusitis is an inflammatory disease of the paranasal sinuses, and rhinitis is an inflammatory disease of the membranes lining the nose. Because sinusitis without associated rhinitis is rare, the term rhinosinusitis is now the accepted nomenclature for this disease complex.18–22 In much of the current literature, however, the terms sinusitis and rhinosinusitis are used interchangeably.

Rhinosinusitis is estimated to affect one in seven adults in the United States and has a significant impact on missed workdays and health care costs.23,24 It is a complication of URI in 5% to 10% of children and 0.5% to 2% of adults. The actual number of people affected by rhinosinusitis may be significantly higher than reported because of the multitude of over-the-counter sinus medications available.

Over the past decade, five major expert organizations have generated guidelines on the definitions and treatments of rhinosinusitis and its subtypes.18–22 There is variation among many of the guidelines’ definitions and recommendations. The information presented in this chapter reflects the areas of greatest consensus among the expert groups.

Rhinosinusitis is the parent term for several subtypes of disease. In acute rhinosinusitis (ARS), symptoms last 4 weeks or less; recurrent ARS is defined as three or more episodes of ARS within 1 year, with resolution of symptoms between episodes; and chronic rhinosinusitis requires symptoms for 12 weeks or longer18–22 (Table 30.1).

Table 30.1 Clinical Forms of Rhinosinusitis Based on Duration of Symptoms

| TYPE | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| Acute | Symptoms present < 4 wk |

| Chronic | Symptoms present > 12 wk |

| Recurrent | >3 acute episodes within 1 yr |

Pathophysiology

Each sinus is lined with ciliated epithelium and mucous goblet cells. Healthy sinuses have relatively few mucus-producing goblet cells, and the cilia beat the mucus toward the ostium of the sinus. The patent ostium allows the free flow of mucus and air from the sinus to the nose. When an ostium is occluded, air and mucus no longer flow freely, new mucus-producing cells develop, and mucostasis results.25

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The diagnosis of ARS is based on three signs or symptoms: nasal congestion, obstruction, or blockage; anterior or posterior purulent rhinorrhea; and facial pain or pressure.18–22 Other suggestive symptoms support the diagnosis but serve only as adjuncts (Box 30.6).

A detailed history to determine the duration, severity, and course of the symptoms is the only readily available tool to differentiate acute viral rhinosinusitis from acute bacterial rhinosinusitis18–2226 (see Fig. 30.2). It can be challenging to differentiate early rhinosinusitis from URI because viral URIs are the most common event precipitating rhinosinusitis and the two may be present concurrently.

The signs and symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis include those of ARS plus a decreased sense of smell.18–22 The symptoms are often more vague and less severe and, by definition, must be present for 12 weeks or longer.

Physical examination will reveal nasal mucosal erythema and edema leading to nasal obstruction. Purulent secretions may also be seen in the nose or the posterior oropharynx. Purulent secretions have the highest positive predictive value for rhinosinusitis of any physical finding.27 The nasal cavities must also be thoroughly inspected for foreign bodies, especially in children.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The diagnosis of ARS is clinical, and in the absence of specific concerns raised by the history and physical examination, no imaging or laboratory tests are warranted. Nasal cultures may be considered during outpatient care in the event of treatment failure.18 Evaluation for systemic disorders predisposing to rhinosinusitis, such as cystic fibrosis or immunodeficiency, can be done on a nonemergency basis.

The infectious organisms causing rhinosinusitis are most commonly viral, then bacterial, then fungal. The most common viruses are rhinovirus, parainfluenza virus, and influenza virus. The most common bacterial pathogens of ARS and recurrent ARS in an immunocompetent host are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Rhinosinusitis pathogens more commonly found in immunocompromised hosts are Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Rhizopus, Aspergillus, Candida, Histoplasma, Blastomyces, Coccidioides, and Cryptococcus. P. aeruginosa is also a common pathogen in patients with cystic fibrosis.28

Noninfectious causes include congenital diseases that inhibit ciliary function, such as cystic fibrosis and Kartagener syndrome; autoimmune diseases, such as Wegener granulomatosis and sarcoidosis; anatomic obstruction, such as from nasal polyps, nasal tumors, or foreign bodies; and facial trauma that directly disrupts sinus drainage.28

Treatment

Intranasal corticosteroids are known to decrease nasal inflammation and may therefore improve ostial patency. These agents have very few identified side effects and are effective in reducing symptoms even as monotherapy.29 Mometasone nasal spray, 200 mcg in each nostril twice daily, may be used.29,30

Topical and oral α-adrenergic decongestants are often prescribed for patients with rhinosinusitis to induce vasoconstriction and reduce nasal mucosal swelling, thereby improving ostial patency and sinus drainage. No controlled clinical trials, however, have examined the efficacy of these agents,28 and the recommendations by the five expert panels are widely disparate.18,20,21 There is no evidence that decongestants are harmful in patients with rhinosinusitis, and therefore the decision regarding their use is left to the clinician. Topical sprays, such as oxymetazoline, two sprays in each nostril every 12 hours, or oral decongestants, such as pseudoephedrine, 60 mg every 6 hours, should be considered on the basis of the risk-to-benefit profile of the individual patient. Decongestant nasal sprays should not be used for longer than 5 days because of the risk for rebound nasal congestion (rhinitis medicamentosa).

Antihistamines are a useful adjunct for patients whose rhinosinusitis has an allergic cause. Diphenhydramine, 25 to 50 mg every 6 hours, loratadine, 10 mg daily, or fexofenadine, 180 mg daily, may all be used. No studies have indicated that antihistamines play a role in nonallergic rhinosinusitis.20

Saline nose drops prevent crusting of nasal secretions and facilitate elimination of these secretions. Physiologic saline and hypertonic saline sprays both increase mucociliary clearance and increase nasal airway patency.31,32 Saline nose drops, normal or hypertonic, may be a useful adjunct to aid in relieving the symptoms of rhinosinusitis.

Guaifenesin is an expectorant that decreases sputum viscosity. It has been shown to improve the ease of sputum expectoration in patients with respiratory infections but has not been demonstrated to aid in the management of rhinosinusitis (Box 30.7).

The vast majority of cases of ARS are caused by viruses, with only 0.5% to 2.0% estimated to have a bacterial cause.33 For this reason, antibiotic treatment should be initiated only in patients for whom the clinician has high suspicion of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (Table 30.2).

Table 30.2 Differentiating Acute Viral from Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis

| VIRAL | BACTERIAL |

|---|---|

| Symptom duration < 10 days | Symptom duration ≥ 10 days |

| Worst symptoms at days 2-3 | Increasing symptoms 5 days after onset |

| Improving symptoms after day 3 | Worsening symptoms after initial improvement |

| Severe symptoms (high fever, unilateral facial or tooth pain, periorbital swelling, orbital cellulitis) |

First-line antibiotic therapy is amoxicillin. If the incidence of β-lactamase–positive S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, or M. catarrhalis infection is high in the area of patient care, adults should be treated with amoxicillin–clavulanate potassium. Alternative first-line agents are certain second- and third-generation cephalosporins. Third- or fourth-generation quinolone antibiotics are also appropriate agents for adult acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Azithromycin or clarithromycin are additional treatment choices, but the local resistance patterns of S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae must first be assessed. The clinician should tailor the choice of antibiotic to the specific resistance patterns of the practice environment. See Box 30.8 for doses and duration of treatment.

Box 30.8 Antibiotic Choices for Acute and Chronic Rhinosinusitis

Amoxicillin, 45 mg/kg per dose PO every 12 hr; adult dose, 500 mg twice daily*

Amoxicillin–clavulanate potassium, 875 mg PO twice daily

Cefuroxime, 500 mg PO twice daily

Cefpodoxime, 400 mg PO twice daily

Azithromycin, 500 mg once then 250 mg daily for 4 additional days

If protracted or severe course, consider anaerobic coverage:

Previously, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim was a popular antimicrobial agent for the treatment of rhinosinusitis; however, as resistance to it has increased, its clinical utility has become limited.20

Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis should be treated with antibiotics for 10 to 14 days (except azithromycin, as noted previously). The patient should be reassessed 3 to 5 days after antibiotic treatment has begun. If no improvement is seen, concern for resistant organisms is raised, and a change in antibiotics should be considered. Chronic rhinosinusitis is treated with a 21-day course of antibiotics, although data supporting the optimum duration of treatment are minimal.22,23

Any patient with evidence of ocular or intracranial extension of sinus disease requires immediate otorhinolaryngologic, ophthalmologic, or neurosurgical consultation (or any combination of the three). Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic therapy, such as with a third-generation cephalosporin and vancomycin, must be started.21 However, because many of these complications require surgical intervention, the choice of antibiotic should be made in conjunction with the surgical service. A patient with this complication must be admitted to the hospital.

Chen YC, Chen CT, Lin CH, et al. A safe and effective way for reduction of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:105–108.

Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL. Rhinosinusitis diagnosis and management for the clinician: a synopsis of recent consensus guidelines. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:427–443.

Viehweg TL, Roberson JB, Hudson JW. Epistaxis: diagnosis and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:511–518.

1 Truelove E. The research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. III: validity of axis I diagnoses. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24:35–47.

2 Annino DJ, Jr., Goguen LA. Pain from the oral cavity. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003;36:1127–1135. vi-vii

3 Lowery LE. The wrist pivot method, a novel technique for temporomandibular joint reduction. J Emerg Med. 2004;27:167–170.

4 Molina OF, dos Santos J, Jr., Nelson SJ, et al. Profile of TMD and bruxer compared to TMD and nonbruxer patients regarding chief complaint, previous consultations, modes of therapy, and chronicity. Cranio. 2000;18:205–219.

5 Rossetti LM, Pereira de Araujo C, Dos R, Rossetti PH, et al. Association between rhythmic masticatory muscle activity during sleep and masticatory myofascial pain: a polysomnographic study. J Orofac Pain. 2008;22:190–200.

6 Levitt SR, McKinney MW. Validating the TMJ scale in a national sample of 10,000 patients: demographic and epidemiological characteristics. J Orofac Pain. 1994;8:25–35.

7 Qerama E. A double-blind, controlled study of botulinum toxin A in chronic myofascial pain. Neurology. 2006;67:241–245.

8 Chang D. Unified hands technique for mandibular dislocation. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:366–367.

9 Chen YC, Chen CT, Lin CH, et al. A safe and effective way for reduction of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:105–108.

10 Viehweg TL, Roberson JB, Hudson JW. Epistaxis: diagnosis and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:511–518.

11 Walker TWM, Macfarlane TV, McGarry GW. The epidemiology and chronobiology of epistaxis: an investigation of Scottish hospital admissions 1995–2004. Clin Otolaryngol. 2007;32:361–365.

12 Awan MS, Iqbal M, Imam SZ. Epistaxis: when are coagulation studies justified? Emerg Med J. 2008;25:156–157.

13 Fuchs FD, Moreira LB, Pires CP, et al. Absence of association between hypertension and epistaxis: a population-based study. Blood Press. 2003;12:145–148.

14 Knopfholz J, Lima-Junior E, Précoma-Neto D, et al. Association between epistaxis and hypertension: a one year follow-up after an index episode of nose bleeding in hypertensive patients. Int J Cardiol. 2009;134:e107–e109.

15 Herkner H, Havel C, Mullner M, et al. Active epistaxis at ED presentation is associated with arterial hypertension. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:92–95.

16 Kucik CJ, Clenney T. Management of epistaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:305–311.

17 Frazee TA, Hauser MS. Nonsurgical management of epistaxis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:419–424.

18 Fokkens W, Lund V, Mullol J. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps Group. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2007. Rhinology. 2007;45(S20):1–139.

19 Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, et al. for the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI); the American Academy of Otolaryngic Allergy (AAOA); the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS); the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI); and the American Rhinologic Society (ARS). Rhinosinusitis: establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;l14(6 Suppl):S155–S212.

20 Slavin RG, Spector SL, Bernstein IL, et al. for the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; and the Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. The diagnosis and management of sinusitis: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;l 16(6, suppl):S13–S47.

21 Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):Sl–S31.

22 Scadding GK, Durham SR, Mirakian R, et al. for the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. BSACI guidelines for the management of rhinosinusitis and nasal polyposis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:260–275.

23 Pleis JR, Lucas JW, Ward BW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 10. 2009;242:1–157.

24 Bhattacharyya N. Contemporary assessment of the disease burden of sinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:392–395.

25 Dykewicz MS. Rhinitis and sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:S520–S529.

26 Lim M, Lew-Gors S, Darby Y, et al. The relationship between subjective assessment instruments in chronic rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 2007;45:144–147.

27 Lacroix JS, Ricchetti A, Lew D, et al. Symptoms and clinical and radiological signs predicting the presence of pathogenic bacteria in acute rhinosinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:192–196.

28 Slavin RG, Spector SL, Bernstein IL. The diagnosis and management of sinusitis: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(suppl):S13–S47.

29 Meltzer EO, Bachert C, Staudinger H. Treating acute rhinosinusitis: comparing efficacy and safety of mometasone furoate nasal spray, amoxicillin, and placebo. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:1289–1295.

30 Nayak AS. Effective dose range of mometasone furoate nasal spray in the treatment of acute rhinosinusitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:271–278.

31 Hauptman G, Ryan MW. The effect of saline solutions on nasal patency and mucociliary clearance in rhinosinusitis patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:815–821.

32 Keojampa BK, Nguyen MH, Ryan MW. Effects of buffered saline solution on nasal mucociliary clearance and nasal airway patency. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:679–682.

33 Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL. Rhinosinusitis diagnosis and management for the clinician: a synopsis of recent consensus guidelines. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:427–443.