142 Marine Food-Borne Poisoning, Envenomation, and Traumatic Injuries

• Scombroid is thought to be caused by breakdown of histidine into histamine in dark-meat marine fish and can be managed with antihistamines.

• Ciguatera poisoning results from the consumption of large tropical predatory reef fish that have bioaccumulated ciguatoxin; it causes gastrointestinal distress and neurologic symptoms.

• Tetrodotoxin blocks sodium channels and can lead to ascending paralysis and respiratory failure.

• box jellyfish (Cubozoa). Portuguese man-of-war (Hydrozoa), and other stinging marine invertebrates envenomate humans via nematocysts that contain a stinging barb and venom.

• The box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) and related species cause the most morbidity and mortality of all marine envenomations.

• Acetic acid immersion is recommended for the treatment of box jellyfish envenomation but may worsen man-o-war envenomation.

• Hot water immersion appears to be an effective treatment of almost all marine envenomations.

• Sea snake venom is neurotoxic and myotoxic. Treatment with antivenom is effective.

• Evaluation for a retained foreign body should be considered with stingray and spiny fish envenomation.

• Wound infection is a common complication of spiny fish and stingray envenomation, and prophylactic antibiotics effective against common pathogens such as Vibrio species should be considered.

• Direct marine injuries are usually abrasions and contusions, but fatal attacks by sharks and large predatory fish do occur.

Marine Food-Borne Poisonings

Pathophysiology

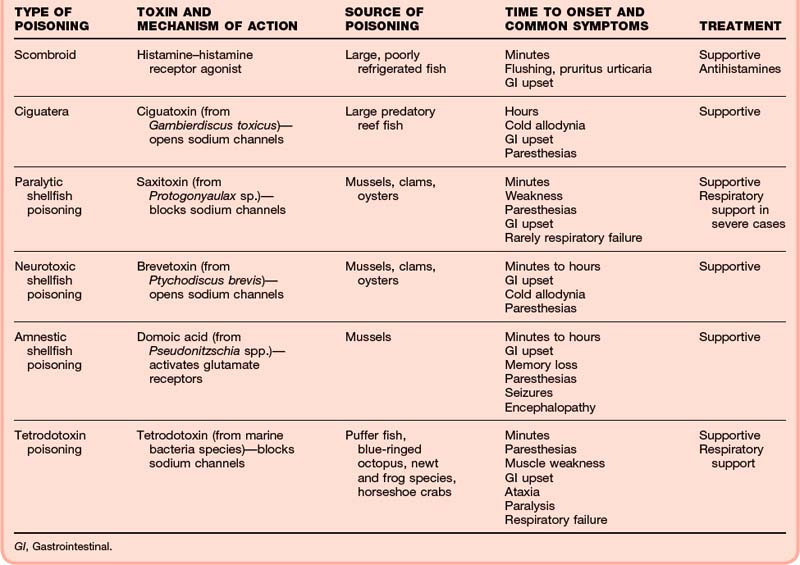

The toxins responsible for the signs and symptoms of marine food-borne illnesses are primarily produced in microorganisms such as dinoflagellates, diatoms, and marine bacteria and are bioaccumulated by shellfish or fish, which are then ingested by humans and result in toxicity. Most of these toxins modulate neuronal and muscle sodium channels. Scombroid is not caused by a preformed toxin but rather by breakdown of histidine into histamine in inadequately stored dark-meat fish. Table 142.1 lists the common marine food-borne poisonings, causative toxins, and typical sources of such poisonings.8

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Table 142.1 lists the typical onset and common symptoms associated with marine food-borne poisonings. Typically, a history of seafood ingestion can be obtained. In most cases the symptoms are manifested within minutes to hours and include a mixture of gastroenteritis (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) and often dramatic neurologic findings.

Treatment

Treatment of marine food-borne poisoning is entirely supportive (see Table 142.1). Attention should be paid to fluid resuscitation and control of nausea and vomiting with antiemetics (ondansetron, 4 to 8 mg intravenously as needed). Although scombroid can be treated with antihistamine therapy, no antidotes are available for any other seafood toxin–mediated poisonings.

Marine Envenomation

Pathophysiology

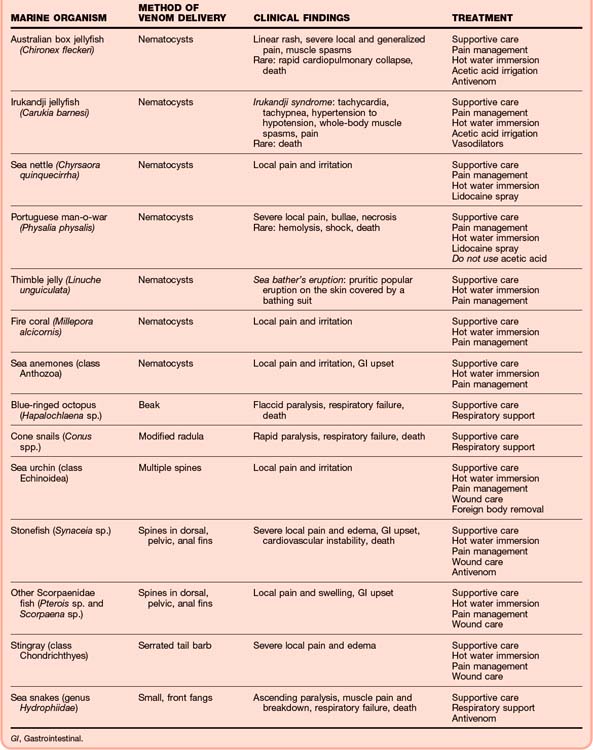

Envenomation can occur from both marine invertebrates and vertebrates. Members of the Cnidaria phylum, which includes the box jellyfish, true jellyfish, Portuguese man-o-war, and sea anemone, have nematocysts with hollow venomous barbs that deliver venom hypodermically. Stingrays have a serrated spine connected to a venom gland located on the tail that can be impaled into unsuspecting victims, whereas the Scorpaenidae family of fish (stonefish, lionfish, scorpion fish) have venomous spines on their fins (Fig. 142.1). Table 142.2 lists the most medically important offending marine organisms and their toxicity.5,9-15

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of marine envenomation depend on the offending organism. Local pain and irritation are the most common symptoms, especially when nematocysts and spines are involved (Fig. 142.2). However, certain marine organisms can cause severe systemic symptoms and even death. The Australian box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) can cause sudden cardiopulmonary collapse.5 The Irukandji jellyfish (Carukia barnesi) can cause Irukandji syndrome, a condition characterized by severe whole-body pain and spasms, tachycardia, and severe hypertension, and it has caused deaths.12 The blue-ringed octopus has tetrodotoxin in its venom, which can cause paralysis and respiratory failure.13 The cone snail’s venom is a complex mixture of peptides that can lead to rapid paralysis and death.14 Stonefish envenomation can result in cardiovascular instability and death, although severe local effects are more common.10 Sea snake venom has both a neurotoxic component, which leads to ascending paralysis, and a myotoxic component, which causes muscle breakdown.15 Table 142.2 summarizes the signs and symptoms of the more significant marine envenomations.

Treatment

Treatment of marine envenomation begins with addressing the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation status. Typically, good supportive care and pain control are all that is needed. Hot water immersion is recommended to control the pain caused by Cnidaria, Scorpaenidae fish, and stingray envenomation and is efficacious because of the heat-labile properties of the neurotoxic component of the venom responsible for the pain. This is typically achieved by immersing the affected body part in water heated to approximately 42° C to 45° C for 20 minutes.16,17 Acetic acid may have a role in inactivating the nematocysts of the box jellyfish and Irukandji jellyfish but should not be used on other types of jellyfish because it may worsen these envenomations.18 Recently, topical lidocaine was shown to help in alleviating the pain and inactivating nematocysts from several different species of Cnidaria, including the Portuguese man-o-war.19 Antivenom therapy is available to treat poisoning by the Australian box jellyfish, the stonefish, and the sea snake.20 Evaluation for a retained foreign body should also be considered, especially with stingray and sea urchin envenomation21,22 (Fig. 142.3). Table 142.2 summarizes the recommended treatments.

Marine Traumatic Injuries

Atkinson PR, Boyle A, Hartin D, et al. Is hot water immersion an effective treatment for marine envenomation? Emerg Med J. 2006;23:503–508.

Currie BJ. Marine antivenoms. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:301–308.

Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103–112.

Isbister GK, Kiernan MC. Neurotoxic marine poisoning. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:219–228.

Noonburg GE. Management of extremity trauma and related infections occurring in the aquatic environment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:243–253.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks—United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:973–979.

2 Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr., et al. 2008 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 26th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2009;47:911–1084.

3 Ahasan HA, Mamun AA, Karim SR, et al. Paralytic complications of puffer fish (tetrodotoxin) poisoning. Singapore Med J. 2004;45:73–74.

4 White J, Warrell D, Eddleston M, Currie BJ, Whyte IM, Isbister GK. Clinical Toxinology—where are we now? J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:263–276.

5 Lumley J, Williamson JA, Fenner PJ, et al. Fatal envenomation by Chironex fleckeri, the north Australian box jellyfish: the continuing search for lethal mechanisms. Med J Aust. 1988;148:527–534.

6 Byard RW, Gilbert JD, Brown K. Pathologic features of fatal shark attacks. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2000;21:225–229.

7 Fenner PJ, Williamson JA, Skinner RA. Fatal and non-fatal stingray envenomation. Med J Aust. 1989;151:621–625.

8 Isbister GK, Kiernan MC. Neurotoxic marine poisoning. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:219–228.

9 Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103–112.

10 Ngo SY, Ong SH, Ponampalam R. Stonefish envenomation presenting to a Singapore hospital. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:506–509.

11 Maretić Z, Russell FE. Stings by the sea anemone Anemonia sulcata in the Adriatic Sea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:891–896.

12 Pereira P, Barry J, Corkeron M, Keir P, Little M, Seymour J. Intracerebral hemorrhage and death after envenoming by the jellyfish Carukia barnesi. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010;48:390–392.

13 Cavazzoni E, Lister B, Sargent P, Schibler A. Blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena sp.) envenomation of a 4-year-old boy: a case report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46:760–761.

14 Rice RD, Halstead BW. Report of fatal cone shell sting by Conus geographus Linnaeus. Toxicon. 1968;5:223–224.

15 Tu At. Biotoxicology of sea snake venoms. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:1023–1028.

16 Atkinson PR, Boyle A, Hartin D, et al. Is hot water immersion an effective treatment for marine envenomation? Emerg Med J. 2006;23:503–508.

17 Nomura JT, Sato RL, Ahern RM, et al. A randomized paired comparison trial of cutaneous treatments for acute jellyfish (Carybdea alata) stings. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:624–626.

18 Hartwick R, Callanan V, Williamson J. Disarming the box-jellyfish: nematocyst inhibition in Chironex fleckeri. Med J Aust. 1980;1:15–20.

19 Birsa LM, Verity PG, Lee RF. Evaluation of the effects of various chemicals on discharge of and pain caused by jellyfish nematocysts. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010;151:426–430.

20 Currie BJ. Marine antivenoms. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:301–308.

21 De La Torre C, Toribio J. Sea-urchin granuloma: histologic profile. A pathologic study of 50 biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:223–228.

22 Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, Ly BT, Davis DP. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33–37.

23 Noonburg GE. Management of extremity trauma and related infections occurring in the aquatic environment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:243–253.

24 Teitelbaum JS, Zatorre RJ, Carpenter S, Gendron D, Evans AC, Gjedde A, Cashman NR. Neurologic sequelae of domoic acid intoxication due to the ingestion of contaminated mussels. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1781–1787.

25 Lehane L, Rawlin GT. Topically acquired bacterial zoonoses from fish: a review. Med J Aust. 2000;173:256–259.