Chapter 347 Manifestations of Liver Disease

Clinical Manifestations

Hepatomegaly

Enlargement of the liver can be due to several mechanisms (Table 347-1). Normal liver size estimations are based on age-related clinical indices, such as the degree of extension of the liver edge below the costal margin, the span of dullness to percussion, or the length of the vertical axis of the liver, as estimated from imaging techniques. In children, the normal liver edge can be felt up to 2 cm below the right costal margin. In a newborn infant, extension of the liver edge >3.5 cm below the costal margin in the right midclavicular line suggests hepatic enlargement. Measurement of liver span is carried out by percussing the upper margin of dullness and by palpating the lower edge in the right midclavicular line. This may be more reliable than an extension of the liver edge alone. The 2 measurements can correlate poorly.

Table 347-1 MECHANISMS OF HEPATOMEGALY

INCREASE IN THE NUMBER OR SIZE OF THE CELLS INTRINSIC TO THE LIVER

Storage

Inflammation

INFILTRATION OF CELLS

Primary Liver Tumors: Benign

Primary Liver Tumors: Malignant

INCREASED SIZE OF VASCULAR SPACE

INCREASED SIZE OF BILIARY SPACE

IDIOPATHIC

Jaundice (Icterus)

Yellow discoloration of the sclera, skin, and mucous membranes is a sign of hyperbilirubinemia (Chapter 96.3). Clinically apparent jaundice in children and adults occurs when the serum concentration of bilirubin reaches 2-3 mg/dL (34-51 µmol/L); the neonate might not appear icteric until the bilirubin level is >5 mg/dL (>85 µmol/L). Jaundice may be the earliest and only sign of hepatic dysfunction. Liver disease must be suspected in the infant who appears only mildly jaundiced but has dark urine or acholic (light-colored) stools. Immediate evaluation to establish the cause is required.

Investigation of jaundice in an infant or older child must include determination of the accumulation of both unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin. Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia might indicate increased production, hemolysis, reduced hepatic removal, or altered metabolism of bilirubin (Table 347-2). Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia reflects decreased excretion by damaged hepatic parenchymal cells or disease of the biliary tract, which may be due to obstruction, sepsis, toxins, inflammation, and genetic or metabolic disease (Table 347-3).

Table 347-2 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF UNCONJUGATED HYPERBILIRUBINEMIA

INCREASED PRODUCTION OF UNCONJUGATED BILIRUBIN FROM HEME

Hemolytic Disease (Hereditary or Acquired)

DECREASED DELIVERY OF UNCONJUGATED BILIRUBIN (IN PLASMA) TO HEPATOCYTE

DECREASED BILIRUBIN UPTAKE ACROSS HEPATOCYTE MEMBRANE

DECREASED STORAGE OF UNCONJUGATED BILIRUBIN IN CYTOSOL (DECREASED Y AND Z PROTEINS)

DECREASED BIOTRANSFORMATION (CONJUGATION)

ENTEROHEPATIC RECIRCULATION

Table 347-3 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF NEONATAL AND INFANTILE CHOLESTASIS

INFECTIOUS

TOXIC

METABOLIC

GENETIC OR CHROMOSOMAL

INTRAHEPATIC CHOLESTASIS SYNDROMES

EXTRAHEPATIC DISEASES

MISCELLANEOUS

Ascites

The onset of ascites in the child with chronic liver disease means that the 2 prerequisite conditions for ascites are present: portal hypertension and hepatic insufficiency. Ascites can also be associated with nephrotic syndrome and other urinary tract abnormalities, metabolic diseases (such as lysosomal storage diseases), congenital or acquired heart disease, and hydrops fetalis. Factors favoring the intra-abdominal accumulation of fluid include decreased plasma colloid osmotic pressure, increased capillary hydrostatic pressure, increased ascitic colloid osmotic fluid pressure, and decreased ascitic fluid hydrostatic pressure. Abnormal renal sodium retention must be considered (Chapter 362).

347.1 Evaluation of Patients with Possible Liver Dysfunction

Adequate evaluation of an infant, child, or adolescent with suspected liver disease involves an appropriate and accurate history, a carefully performed physical examination, and skillful interpretation of signs and symptoms. Further evaluation is aided by judicious selection of diagnostic tests, followed by the use of imaging modalities or a liver biopsy. Most of the so-called liver function tests do not measure specific hepatic functions: a rise in serum aminotransferase levels reflects liver cell injury, an increase in immunoglobulin levels reflects an immunologic response to injury, or an elevation in serum bilirubin levels can reflect any of several disturbances of bilirubin metabolism (see Tables 347-2 and 347-3). Any single biochemical assay provides limited information, which must be placed in the context of the entire clinical picture. The most cost-efficient approach is to become familiar with the rationale, implications, and limitations of a selected group of tests so that specific questions can be answered. Young infants with cholestatic jaundice should be evaluated promptly to identify patients needing surgical intervention.

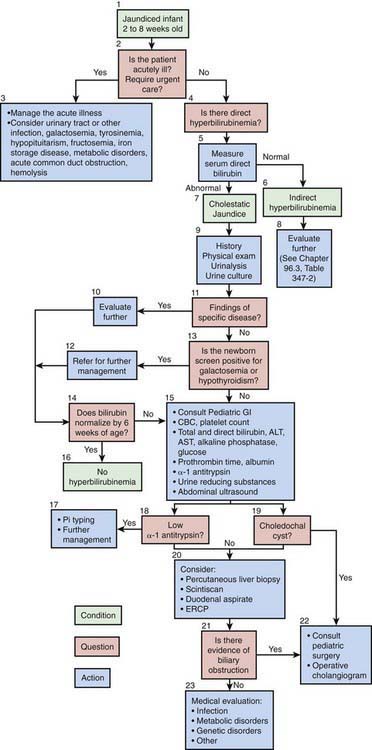

Diagnostic Approach to Infants with Jaundice

The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition has published an algorithm for the evaluation of cholestatic jaundice in neonates and young infants. Well-appearing infants can have cholestatic jaundice. Biliary atresia and neonatal hepatitis are the most common causes of cholestasis in early infancy. Biliary atresia portends a poor prognosis unless it is identified early. The best outcome for this disorder is with early surgical reconstruction (45-60 days of age). History, physical examination, and the detection of a conjugated hyperbilirubinemia via examination of total and direct bilirubin are the 1st steps in evaluating the jaundiced infant (Fig. 347-1). Consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist should be sought early in the course of the evaluation.

Batres LA, Maller ES. Laboratory assessment of liver function and injury in children. In: Suchy FS, Sokol RJ, Balistreri WF, editors. Liver disease in children. ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:155-170.

Moyer V, Freese DK, Whitington PF, et al. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition: Guideline for the evaluation of cholestatic jaundice in infants: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:115-128.

Balistreri WF. Pediatric hepatology. A half-century of progress. Clin Liver Dis. 2000;4:191-210.

Balistreri WF. Bile acid therapy in pediatric hepatobiliary disease: the role of ursodeoxycholic acid. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:573-589.

Bezerra JA, Balistreri WF. Cholestatic syndromes of infancy and childhood. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2001;12:54-65.

Feranchak AP, Ramirez RO, Sokol RJ. Medical and nutritional management of cholestasis. In: Suchy FS, Sokol RJ, Balistreri WF, editors. Liver disease in children. ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:195-238.

Garcia-Tsao G. Current management of the complications of cirrhosis and portal hypertension: variceal hemorrhage, ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:726-748.

Ryckman FC, Alonso MH. Causes and management of portal hypertension in the pediatric population. Clin Liver Dis. 2001;5:789-818.

Ryckman FC, Alonso MH, Bucuvalas JC, Balistreri WF. Liver transplantation in children. In: Suchy FS, Sokol RJ, Balistreri WF, editors. Liver disease in children. ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:949-974.