CHAPTER 22 Managing submandibular glands

History

In search of the artistically pleasing neck through the addition of subplatysmal fat contouring and submandibular gland treatment

1968: Millard – Submandibular lipectomy.

1972: Millard – Submental and submandibular lipectomies in conjunction with rhytidectomy.

1978: Connell – Contouring the neck in rhytidectomy by lipectomy and a muscle sling.

1979: Aston – Platysma muscle alterations in rhytidoplasty.

1983: Owsley Jr. – SMAS-platysma face lift: a bidirectional cervicofacial rhytidectomy.

1985: Courtiss – Suction lipectomy of the neck.

1985: Giampapa – Neck recontouring with suture suspension and liposuction.

1990: Feldman – Corset platysmaplasty.

1991: de Pina – Aesthetic resection of the submandibular gland.

2006: Sullivan – MRI study demonstrating increasing submandibular gland ptosis with age.

Physical evaluation

• Key features of the aged neck include platysmal banding, pre- and/or subplatysmal fat deposits, skin laxity, and submandibular gland ptosis.

• Indications include young patients with a prematurely aged neck, or older patients with the neck contour issues as a prominent aspect of facial aging.

• Signs of cervicofacial aging may initially manifest as faint vertical platysmal bands overlying the thyroid cartilage and hyoid.

• These progress to longer, more pronounced bands as more support is lost from the retaining ligaments and the platysma descends further.

• A cervical obliquity, which may be composed of pre- and subplatysmal fat deposits.

• Submental fullness may be addressed with conservative contouring of pre- and or subplatysmal fat, but one must be concerned that this does not unmask submandibular gland ptosis.

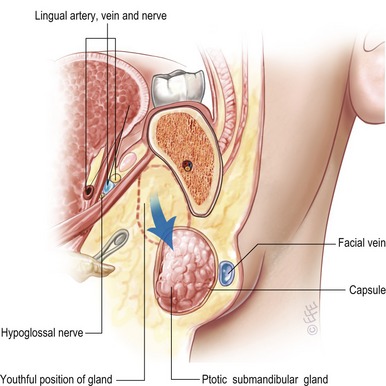

• Fullness laterally below the mandible, may be the result of the ptotic submandibular gland, and this may be addressed via gland resection or suspension.

• Patients undergoing other aesthetic facial surgical procedures may accentuate the appearance of untreated submandibular gland ptosis.

Technical steps

Ligaments in the neck, analogous to the retaining ligaments in the cheek, help suspend the soft-tissues. The mandibular ligaments affix the overlying skin to the inferior aspect of the mandible, and help to define the anterior aspect of the jowls in the aged face. The thin fascial support in the preauricular region is the platysma-auricular ligament, and attaches the posterosuperior platysma to the skin. Anteriorly, the skin is tethered to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system SMAS and platysma via the anterior platysma–cutaneous ligaments. These ligaments check the descent of the soft-tissues of the neck in aging, and are disrupted to allow for proper redraping of the skin during neck rejuvenation.

SMAS suspension/platysmal plication

The anterior platysma is approached through a transverse submental incision (Fig. 22.1). The submental skin and a smooth, consistent layer of adjoining fat are then undermined inferiorly to the level of the cricoid. To correct the platysmal bands, the muscle is freed on the edges from the deeper subplatysmal fat and anterior bellies of the digastric muscles. The platysmal edges are grasped with forceps and brought together in the midline. The excess tissue is then resected as described below, and the edges brought together with interrupted and then a running suture from inferior to superior.

Submandibular gland suspension and resection

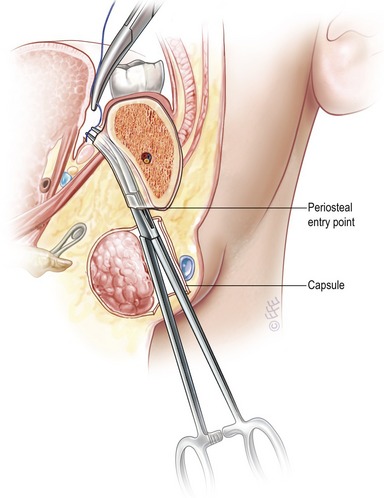

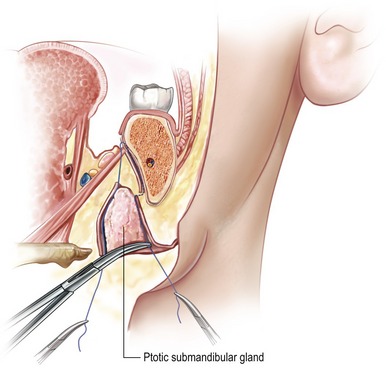

As before, the neck is approached through a submental incision. The dissection is continued beneath the platysma, where the submandibular gland has been marked out preoperatively. In this way, the surgeon can obtain direct visualization of the submandibular capsule. A 1.5 cm incision is made in the capsule along the anterior-inferior surface, parallel to the body of the mandible. Careful dissection around the gland releases any inferior or lateral capsular adhesions and results in mobilization of the gland within the capsule. A blunt snap is inserted until the inferior border of the mandible is encountered, and then is advanced along the lingual aspect of the mandibular body in a subperiosteal plane. This is continued until the oral mucosa tents over the tip of the snap. At this point, a 2–3 mm incision is carefully made with a #15 scalpel. The instrument tip is then delivered into the oral cavity and a 2-0 suture end is grasped and brought back out through the neck incision (Fig. 22.2).

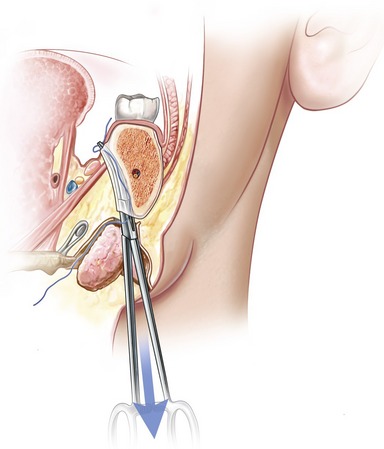

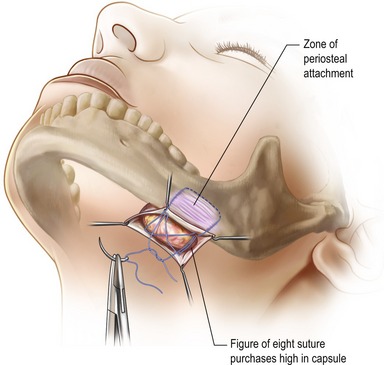

A second pass is then performed, also from within the glandular capsule, but lateral to the gland this time. The periosteal tunnel created for this suture is parallel to, but 3 cm anterior to, the initial pass. The opposite end of the free suture is grasped and pulled down into the neck (Fig. 22.3). After both ends of the suture have been retracted caudally, mild traction on the suture ensures adequate purchase of a sling of periosteum to provide support for the gland (Fig. 22.4). This is the zone of periosteal adhesion. The gland is elevated to the level of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and the inferior border of the mandible with gentle digital pressure. The knot is then cinched, tied, and the gland’s elevated position secured (Fig. 22.5).

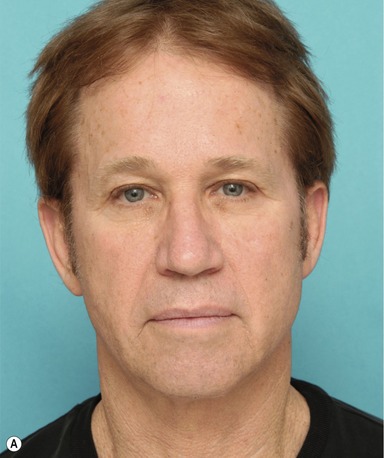

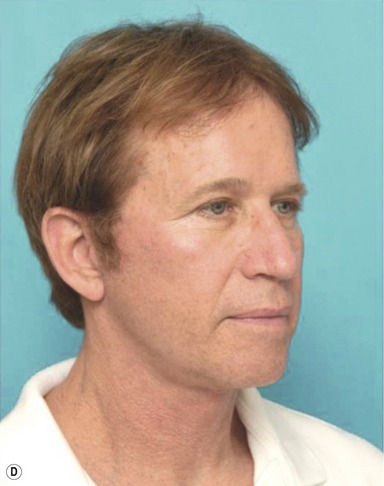

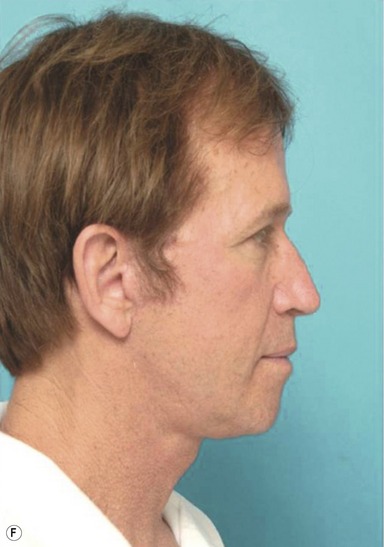

Fig. 22.6 Photographs of a 59-year-old male patient with a ptotic submandibular gland, who underwent submandibular gland suspension. A, Preoperative photograph, anterior view. B, Postoperative photograph, anterior view. C, Preoperative photograph, oblique view. D, Postoperative photograph, oblique view. E, Preoperative photograph, lateral view. F, Postoperative photograph, lateral view. Redrawn from Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Patrick K. Sullivan, M. Brandon Freeman and Scott Schmidt. Contouring the aging neck with submandibular gland suspension July–August 2006. With permission from Elsevier.

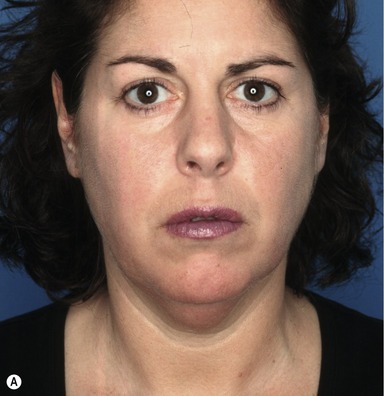

Fig. 22.7 Photographs of a 43-year-old female patient who underwent pre- and subplatysmal fat contouring without contouring of the submandibular gland. A, (Female AP preop): Preoperative photo, anterior view. B, (Female AP postop): Postoperative photo, anterior view. C, (Female oblique preop): Preoperative photo, oblique view. D, (Female oblique postop): Postoperative photo, oblique view. E, (Female lateral preop): Preoperative photo, lateral view. F, (Female lateral postop): Postoperative photo, lateral view.

Postoperative care

Following procedures for neck rejuvenation, postoperative care starts in the operating room. This includes an emergence from sedation that is ideally smooth, without hypertension, coughing, or retching. Attention to hemostasis and strict adherence to activity instructions, will help minimize the risk of hematoma. Patients should be instructed to sleep with their head elevated, with their neck extended slightly to about 95 degrees. To assist in this, patients are urged to place a wedge beneath the head when sleeping. Also, NSAIDs and anticoagulants should be offered for at least a week after neck rejuvenation. Most importantly, by ensuring good communication between surgeon and patient, increased cooperation and better outcomes can be achieved.

Complications

Summary of steps

1. Obtain an accurate history and physical examination, including preoperative photos.

2. Pair the correct procedure to the defect to be addressed.

3. Prep the intraoral surfaces with betadine, and perform intraoral nerve blocks of the mandibular nerve.

4. After infiltrating the areas of planned incisions with local anesthetic, perform the lateral pre- and posterior auricular rhytidectomy incisions and the 3.5 cm submental incisions for access to the neck.

5. Submental skin is then undermined inferiorly to the level of the cricoid.

6. The platysma is divided in the midline, and freed from the deeper subplatysmal fat and anterior bellies of the digastric muscles.

7. Subplatysmal fat is resected with scissors to correct the cervicomental convexity.

8. Exposing the submandibular gland, a 1.5 cm incision is made in the capsule along the anterior–inferior surface, and the gland mobilized within the capsule.

9. A blunt snap is advanced along the lingual aspect of the mandibular body in a subperiosteal plane, and through a 2–3 mm incision, is delivered into the oral cavity.

10. A 2-0 suture end is grasped and brought back out through the neck incision.

11. A second pass is then performed, lateral to the gland this time. The opposite end of the free suture is grasped and pulled down into the neck, and tightened to secure the gland in an elevated position.

12. The incised glandular capsule is imbricated with permanent suture to bolster the suspension sling inferiorly.

13. The intraoral incisions are closed with chromic suture.

14. The cut platysmal edges are brought together in the midline, the excess tissue resected, and the edges re-approximated with interrupted or running sutures.

15. The submental and rhytidectomy incisions are closed in layers, with the last being a fine running nylon suture.

16. The incision is cleaned and dressed with a thin layer of bacitracin.

17. Include meticulous hemostasis and avoidance of hypertension postoperatively in an effort to prevent or minimize postoperative complications.

18. Ensure postoperative follow-up and evaluating results critically and honestly.

Baker DC. Face lift with submandibular gland and digastric muscle resection: radical neck rhytidectomy. Aesthetic Surg J. 2006;26:85–92.

Codner MC, Nahai F. Submandibular gland I: an anatomic evaluation and surgical approach to submandibular gland resection for facial rejuvenation. Discussion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(4):1155–1156.

de Pina DP, Quinta WC. Aesthetic resection of the submandibular salivary gland. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;5:779.

Feldman JJ. Corset platysmaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85:333.

Gardetto A, Dabernig J, Rainer C, Piegger J, Piza-Katzer H, Fritsch H. Does a superficial musculoaponeurotic system exist in the neck? An anatomic study by the tissue plastination technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(2):664–672.

Goddio AS. Skin retraction following suction lipectomy by treatment site: a study of 500 procedures in 458 selected subjects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(1):66–75.

Ramirez OM. Comprehensive approach to rejuvenation of the neck. Facial Plast Surg. 2001;17:129.

Singer DP, Sullivan PK. Submandibular gland I: an anatomic evaluation and surgical approach to submandibular gland resection for facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(4):1150–1154.

Sullivan PK, Freeman MB, Schmidt S. Contouring the aging neck with submandibular gland suspension. Aesthet Surg J. 2006;26(4):465–471.

Zins JE, Fardo D. The “anterior-only” approach to neck rejuvenation: an alternative to facelift surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(6):1761–1768.