Managing lower limb arterial insufficiency, the diabetic foot and major amputations

Chronic lower limb ischaemia

Natural history of intermittent claudication

The fate of the leg: The clinical course of intermittent claudication is largely benign. Three quarters of patients either stay the same or improve their walking distance. Only 5–10% with claudication will need endovascular or surgical intervention by 5 years for worsening claudication or severe limb ischaemia. Only 2% with claudication progress to needing major amputation. Smoking increases the risk of reconstructive surgery or major amputation. Patients with diabetes have a higher risk of major amputation in part due to small and distal vessel atherosclerosis.

The fate of the patient: Lower limb PAD is a marker of systemic atherosclerosis. The severity of PAD (as estimated by ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) is associated with increasing coronary artery disease and the overall mortality rate. Some 10% of claudicants have a non-fatal cardiovascular event (myocardial infarction or stroke) within 5 years and the 5-year mortality rate is 30% with ¾ being cardiovascular. Smoking increases mortality rates amongst claudicants by 1.5–3.0 times.

Severe ischaemia

The first manifestations of severe ischaemia develop in the foot and include:

• Intolerable rest pain initially at night, later becoming continuous during the day

• Trophic skin changes—atrophic shiny red skin of the leg; ischaemic ulcers between toes, in foot pressure areas or on the leg

• Patchy necrosis of the toes or skin of the foot

If untreated, a very small proportion improve and lose their pain, but most smoulder on with intolerable pain or progress to necrosis. Once the deep tissues of the foot become necrotic, local defences are overwhelmed and infection spreads widely in vulnerable ischaemic tissue, especially in diabetics. This causes wet gangrene and, ultimately, death from sepsis and multi-organ dysfunction. This sequence rarely runs its course since rest pain is so severe and signs of sepsis so obvious that vascular reconstruction or amputation becomes unavoidable.

Critical ischaemia: Critical ischaemia occurs when arterial insufficiency is so severe that it threatens the viability of foot or leg. This is formally defined by a European consensus document as follows: persistently recurring rest pain requiring regular analgesia for more than 2 weeks, or ulceration or gangrene affecting the foot, plus an ankle systolic pressure of less than 50 mmHg (Note: in diabetics, absent ankle pulses on palpation replace pressure as calcification may artificially elevate pressures).

Managing lower limb ischaemia

Investigation of chronic lower limb arterial insufficiency

The ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI): All claudication patients should have resting ankle systolic pressures measured in clinic to confirm the diagnosis, plus a full blood count to exclude polycythaemia and thrombocythaemia. Pressure is measured using a Doppler ultrasound flow detector (see Fig. 5.9, p. 72). Normal pressure is slightly above brachial systolic whilst patients with claudication usually range between 50 and 120 mmHg. Results are often expressed as a ratio, the ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI), with normal values from 0.9 to 1.2. Note that Doppler pressures can be misleading; experience is needed in taking and interpreting measurements, and radical treatment should not be based on random pressure measurements. Values may be spuriously elevated in patients with diabetes owing to calcification in the arterial media which prevents cuff compression. In non-classical exercise-induced leg pain or those with a good history of claudication but normal resting ABPI, a treadmill test with pre- and post-exercise pressure or ABPI helps the diagnosis. A drop in ankle pressure after exercise gives an indication of arterial disease severity and the recovery rate an indication of collateral compensation.

Duplex ultrasonography: This combines greyscale ultrasound imaging (GSUS) and colour Doppler blood flow estimation. GSUS allows estimation of plaque narrowing and colour Doppler allows estimation of flow velocities, which increase in areas of stenosis. These methods provide a ‘road map’ of atherosclerosis in the arterial tree and are usually performed in a vascular laboratory by specialist ultrasonographers. It is non-invasive and rarely requires intravenous contrast media. There is substantial user dependency in the results.

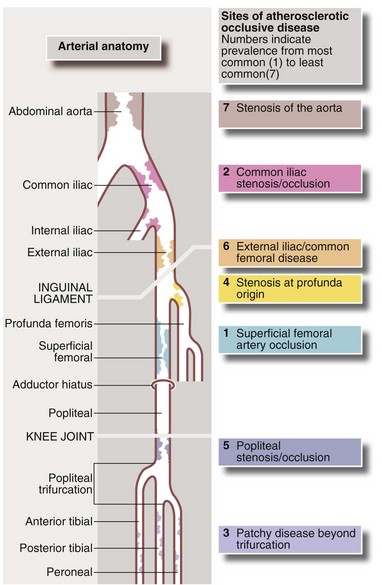

Arteriography (see Ch. 5): Arteriography should be reserved for patients thought to require angioplasty or reconstructive surgery. It maps the arterial system (see Fig. 41.1), showing sites and severity of stenoses and occlusions, the quality of inflow (arteries feeding the area of concern) and the runoff (arteries beyond the main obstruction, see Fig. 41.2). Arteriography is sometimes used wrongly by non-specialists to assess chronic arterial insufficiency but it cannot measure blood flow to the tissues or dynamic circulatory responses to exercise; it helps only with the mechanics of revascularisation. Traditional arteriography is performed via direct arterial puncture but carries risks of vessel trauma and high doses of contrast aggravating chronic renal impairment. It is being replaced by less invasive CT and MR angiography which use lower doses of intravenous contrast media.

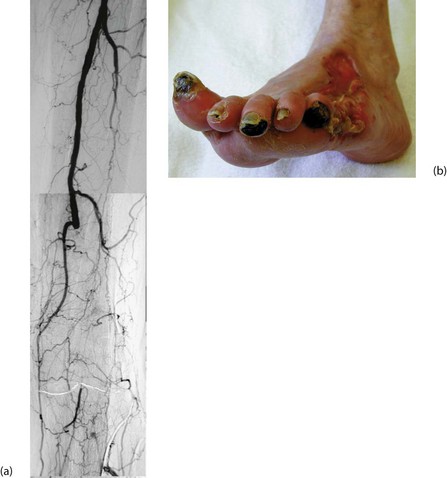

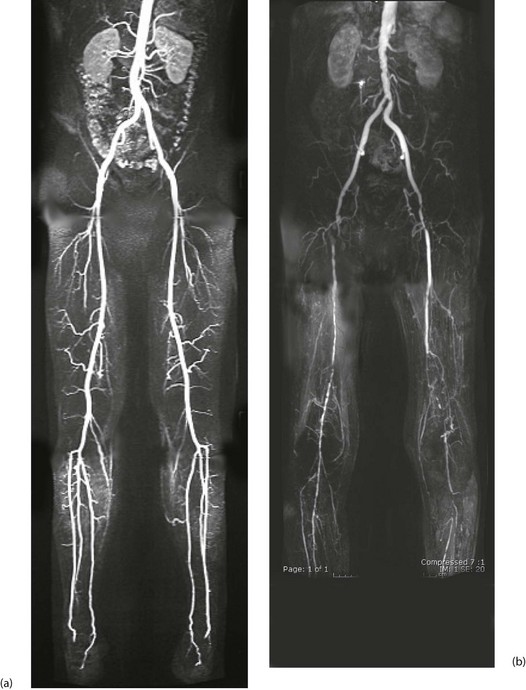

Fig. 41.2 Arteriograms comparing the normal with typical patterns of arterial obstruction affecting the lower limbs

(a) This magnetic resonance angiogram is entirely normal, showing smooth, regular arterial walls, all branches intact and three normal infra-inguinal arteries below knee on each side. (b) This composite subtraction arteriogram was performed because the patient suffered bilateral severe claudication. The aorta is irregular and narrowed by atherosclerosis from above the renal arteries to the bifurcation. The common, internal and proximal external iliacs are normal and smooth but the right external iliac is occluded and the left stenosed. Both profunda femoris arteries are occluded. The superficial femoral arteries are both diseased and occluded distally. On the left side, collaterals are visible around the knee area. The infrageniculate vessels are diseased on both sides with stenoses and occlusions. Reconstruction would have been extensive, difficult and risky, and hence conservative management alone was undertaken, in the absence of rest pain or tissue loss

Approach to management of chronic lower limb arterial insufficiency

Treatment options range from conservative or ‘expectant’ treatment for most, to reconstructive procedures for the few with severe ischaemia. Treatments are summarised in Box 41.1.

Conservative management: In intermittent claudication, management starts with lifestyle measures such as stopping smoking, attention to diet (reduced fat, more fruit and vegetables, weight reduction) and systematic exercise. Cigarette smoking is a primary risk factor in causing atherosclerosis and a secondary risk factor in causing deterioration, as well as causing occlusions or stenoses of angioplasty or graft after reconstruction. Symptoms are more likely to resolve (by collateral development) if the patient stops smoking. Giving up is difficult as nicotine is highly addictive but smoking cessation programmes can help as well as pharmacological aids such as nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion (Zyban) and varenicline (Champix). All family members need to give up together to reinforce the message.

Mild to moderate claudication: Most patients are optimally treated with best medical management and lifestyle advice. Symptoms often improve spontaneously over 6–18 months, especially if the patient stops smoking, exercises regularly and loses excess weight. Simple advice to walk more slowly and use a walking stick often greatly extends the claudication distance. Supervised exercise programmes produce a sustained increase in walking distance but need to continue for at least 3 months to show benefit—there is often a problem with compliance. These programmes are not yet offered in the NHS.

Disabling claudication: Disabling claudication usually requires treatment unless the patient is too unfit even for angiography. Symptoms may include severe exercise restriction in younger patients or markedly worsening symptoms, especially if proximal arterial obstruction is the cause (shown by absent femoral pulses), which is often easily treated by angioplasty. Reconstructive surgery is sometimes needed.

Techniques of revascularisation for chronic arterial insufficiency

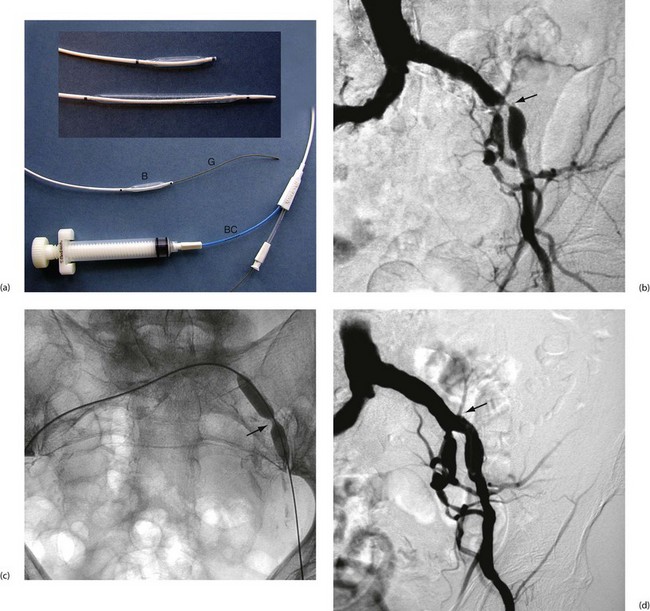

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA): PTA involves cannulating an artery (usually the common femoral but occasionally the brachial), introducing a guide-wire into this remote artery and advancing it to lie across the stenosis. A balloon catheter is passed over the wire and into position (see Fig. 41.3) and the balloon inflated to a high pressure (5–15 atmospheres), crushing the atheroma into the arterial wall to relieve the obstruction. Success is very operator-dependent and also depends upon the site, length and nature of the diseased artery. PTA is most effective for isolated short stenoses in iliac arteries. With increasing experience, longer stenoses and occlusions in smaller vessels can be tackled, avoiding the need for major surgery. The method is less successful for distal calf arteries. Angioplasty often provides symptom improvement for a few years but disease progression (and failure to modify lifestyle) is a limiting factor.

Fig. 41.3 Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty

(a) Balloon angioplasty equipment. This catheter is used for balloon dilatation of arterial stenosis. First, an artery some distance from the stenosis (usually the femoral) is punctured with a needle. A flexible guide-wire G is passed through the needle, along the artery and manipulated across the stenosis. The catheter is then threaded over the guide-wire until the distal balloon B (which is designed to only be inflated to a predetermined diameter) lies within the stenosis. The balloon is then inflated to high pressure using a special syringe attached to the balloon channel BC. Note the radio-opaque markers at each end of the balloon to allow it to be sited radiographically. (b) Arteriogram showing a tight stenosis at the distal end of the left common iliac artery (arrowed). (c) Catheter access proved impossible via the left femoral artery, so a guide-wire was passed from the right femoral, over the bifurcation and across the stenosis. An angioplasty balloon catheter was then guided across the stenosis. As it was inflated the ‘waist’ caused by the arterial stenosis became clearly visible (arrowed). With further inflation to 4 atmospheres pressure, the waist disappeared. (d) Appearance of the arteries post angioplasty. This procedure was completed in under an hour on a day-case basis under local anaesthesia and proved durable over several years

Arterial reconstructive surgery: Arterial reconstructive surgery began in the 1950s with open removal of atheromatous plaques and thrombus from the aorta and iliac arteries. This is known as thrombo-endarterectomy, and is technically difficult, bloody and time-consuming. It has been replaced by bypass grafting, except for carotid endarterectomy, which remains the standard operation for stenosis and for isolated common femoral artery occlusions.

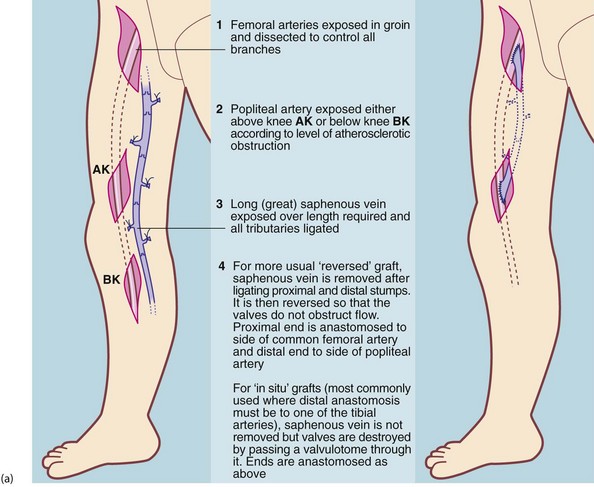

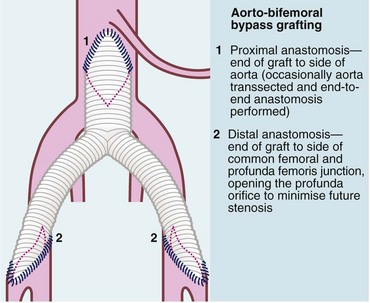

The most common procedures are synthetic ‘trouser’ grafting for aorto-iliac (supra-inguinal) disease and femoro-popliteal grafting using saphenous vein, for infra-inguinal disease (see Figs 41.4 and 41.5). However, a range of other bypasses and endarterectomy techniques sometimes have to be employed to cope with non-standard disease.

Fig. 41.4 Aorto-bifemoral bypass for aorto-iliac disease using a trouser or ‘Y’ graft

A Dacron bifurcation graft or prosthesis is used to bypass the aorto-iliac segment when it is occluded or stenosed, or to replace it when aorta and iliacs are aneurysmal. In the latter case, the distal anastomoses are to the iliac arteries not the femorals so as to maintain pelvic perfusion.

Aorto-iliac disease: The usual surgical procedure is a Dacron trouser or ‘Y’ graft (see Fig. 41.4), anastomosed to the side of the aorta below the renal arteries and to both common femorals below the inguinal ligament (aorto-bifemoral graft). This is a major operation, needing a laparotomy to access and cross-clamp the aorta and carries a mortality risk of about 5%. In patients with critical ischaemia but poor physiological reserve, legs can be revascularised using extra-anatomic synthetic grafts with a lower operative risk. Examples include a cross-over graft to supply blood from one femoral artery to the other or an axillo-bifemoral graft, supplying blood from one axillary artery to both femorals, tunnelling the graft subcutaneously along the lateral chest and abdominal wall.

Femoro-popliteal disease: The superficial femoral artery is the most commonly obstructed peripheral artery. If PTA is unsuitable, femoro-popliteal bypass grafting is employed using an autogenous vein graft. The long (great) saphenous vein (LSV) is dissected from groin to knee, its tributaries ligated and then reversed proximal to distal so the valves do not obstruct flow. An end-to-side anastomosis is performed at each end. If the LSV is unsuitable (i.e. diseased, small diameter or previously removed for CABG), the LSV from the other leg or veins from the arm can be used. An alternative technique leaves the vein in situ and destroys the valves with a valvulotome. As the vein tapers from proximal to distal, this allows bypasses to tibial, dorsalis pedis artery or smaller foot arteries for distal disease. These infrapopliteal or femoro-distal grafts are used only for severe ischaemia because of the higher risk of graft occlusion.

Other therapies for arterial insufficiency

Intravenous and intra-arterial drug therapies: Drug therapy has no substantial effect in relieving claudication or severe ischaemia but recent research has examined gene therapy and local stimulation of angiogenesis (new blood vessel formation) in patients with critical limb ischaemia. However, the results are currently not yet robust enough to employ clinically.

Acute lower limb ischaemia

Pathophysiology

The lower (or upper) limb can become acutely ischaemic from embolism or thrombosis.

Embolism: A large embolus impacting in a major distributing artery causes the distal blood supply to cease abruptly; since the distal arteries are not usually atherosclerotic, collateral networks have not developed and ischaemia is all the more severe. Most large emboli originate in the heart, as a result of atrial fibrillation or mitral stenosis or both (left atrial thrombus), or of myocardial infarction (mural thrombus). Emboli usually impact at branching points where the lumen abruptly narrows. Common sites are the aortic bifurcation (saddle embolus), the common femoral bifurcation and the popliteal trifurcation. Aortic or popliteal aneurysms can be a source of embolism if thrombus accumulated in the sac travels distally (see Figs 41.6 and 41.7).

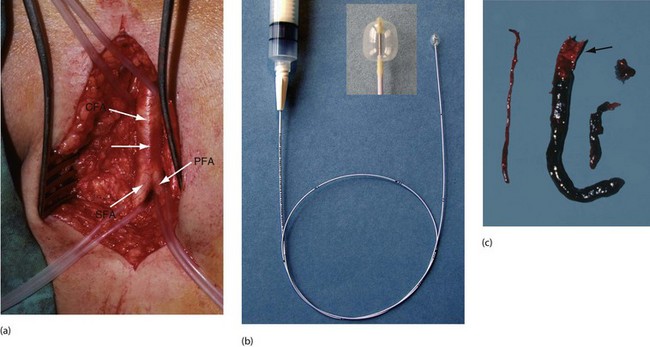

Fig. 41.7 Femoral artery embolectomy

(a) Surgical exposure of the femoral artery bifurcation, usually performed under local infiltration anaesthesia (but with full monitoring). The common femoral artery CFA, the profunda femoris PFA and the superficial femoral artery SFA are dissected cleanly and silicone slings placed around each artery. A transverse arteriotomy is made just proximal to the bifurcation (position arrowed). (b) A Fogarty balloon catheter is passed distally, the balloon is gently inflated and the catheter withdrawn to extract embolic and thrombotic material. This is performed in stages until the catheter can be passed to ankle level and back-bleeding occurs. (c) Embolic material removed at operation from the superficial femoral artery and beyond using a Fogarty catheter. Note the paler embolic material (arrowed) and the darker thrombus propagated beyond it

Thrombosis: Thrombotic causes include thrombosis of a popliteal aneurysm and acute occlusion of a previous bypass graft or angioplasty site. Occasionally, widespread thrombosis occurs in normal arteries causing acute ischaemia. This can be a complication of blood disorders including polycythaemia vera, thrombocythaemia or leukaemias, in nephrotic syndrome or in hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic states in diabetics.

Clinical features of acute lower limb ischaemia (Box 41.3)

The condition usually presents as a sudden onset of pain, coldness and pallor, extending from the foot for a variable distance up the leg. If the blood supply is completely cut off, nerve ischaemia causes loss of sensation and then muscle paralysis after an hour or two (the six Ps—see Ch. 40, p. 489). Acute severe arterial occlusion must be recognised quickly as limb viability is in immediate danger and urgent steps are needed to revascularise it. Unfortunately, this urgency is not always appreciated by the patient, nursing staff or inexperienced doctors. Even with successful revascularisation, ischaemic changes may already be irreversible and with late intervention, there is a serious risk of muscle necrosis and permanent nerve injury from reperfusion injury and/or compartment syndrome (see Ch. 17, p. 235).

Principles of managing the acutely ischaemic limb

Thrombosis or embolism?

In acute ischaemia, the speed of treatment is the key to success. Any patient with sensory loss affecting more than just the toes, especially with evidence of muscle weakness, requires immediate treatment with embolectomy, thrombectomy or bypass graft (see Fig. 41.4, 41.5, p. 502). In limbs that have been profoundly ischaemic, fasciotomies at the time are often required to prevent compartment syndrome. Thrombolysis is now rarely undertaken, except for unblocking a thrombosed bypass graft in a patient whose foot is predicted to remain viable for at least 12 hours.

Embolectomy

Embolectomy is often performed under local anaesthesia but the patient and theatre should be prepared for GA just in case; full monitoring should be applied. The patient has usually been anticoagulated with heparin. A groin incision exposes the femoral artery bifurcation, the vessels are all temporarily clamped and an incision (arteriotomy) made in the common femoral artery (Fig. 41.7) which may reveal the obstructing clot. A Fogarty balloon catheter is then passed gently into each main vessel in turn, proximally and distally for 10 cm or so, the balloon is inflated gently and the catheter drawn back to sweep out any obstructing clot. This is repeated 10 cm further each time until the distal limit is reached. The operation is successful if clot is retrieved and blood flows back (‘back-bleeding’) from each vessel as it is unclamped. If the embolectomy catheter will not pass easily, this usually indicates acute-on-chronic thrombosis. Immediate arteriography and surgical treatment are required as delay carries a high rate of limb loss and death.

The diabetic foot

Pathophysiology of the diabetic foot

Several factors may contribute to diabetic foot problems:

• Neuropathy. Microangiopathy probably causes peripheral neuropathies affecting motor, sensory and autonomic nerves. Affected motor nerves supply the small muscles of the foot and the consequent unmodified traction of the calf muscles distorts the morphology and weight-bearing characteristics of the foot. Sensory neuropathy lessens pain sensation and hence awareness of potential injury from ill-fitting footwear and foreign bodies in shoes. Damaged autonomic nerves disrupt vascular control and cause loss of sweating. Ulceration and infection in neuropathic feet are often painless and hence are often neglected by the patient

• Arteriovenous communications. These open beneath the skin, perhaps diverting nutrient flow away from it. Damaged tissue thus heals poorly and is vulnerable to infection, even if the injury or pressure damage is minor. This may also explain why an ischaemic diabetic foot can be warm and pink

• Arterioles. In a few cases, these become narrowed and restrict capillary perfusion

• Impaired intermediary tissue metabolism and a glucose-rich tissue environment. Both of these favour bacterial growth and spreading infection

• Obliterative atherosclerosis. Diabetics have a markedly increased predisposition to arterial insufficiency. Although 1–5% of the general population have diabetes, 25% of patients with lower limb ischaemia have diabetes. Atherosclerotic disease in diabetic patients follows the usual pattern (although often more distal) but tends to develop at a younger age

Identifying the causes of diabetic foot problems: Most diabetic foot problems can be identified as primarily neuropathic or primarily atherosclerotic but some have elements of both. The term ‘neuro-ischaemic’ foot is sometimes used but is not clinically precise. Typically, the neuropathic foot is painless, red and warm with strong pulses, whereas the atherosclerotic foot without neuropathy is pale, painful, cold and pulseless. However, when both occur together, the diabetic trap is that the limb can be seriously ischaemic yet painless, warm and pink. If the foot is neuropathic and pulseless, only arteriography or duplex scanning will properly demonstrate the arterial insufficiency.

Patients most at risk of neuropathic foot complications are elderly, poorly controlled, maturity-onset (type 2) diabetics and younger patients with longstanding type 1 diabetes. Similarly, patients with diabetic renal or retinal complications have an increased risk of foot problems. Recognising the ‘at-risk’ foot, i.e. the neuropathic foot, before trouble strikes is fundamental, as virtually all neuropathic foot complications can be prevented with proper education, regular inspection and chiropody (podiatry) (Box 41.4).

Clinical presentations of diabetic foot complications: Foot complications of diabetic neuropathy present in four main ways (see Fig. 41.8):

• Painless, deeply penetrating ulcers. These usually develop in pressure areas caused by distortion of foot morphology, often beneath the first or fifth metatarsal head. The infecting organism is usually Staphylococcus aureus. Infection and necrosis spread through the plantar spaces and along tendon sheaths. Infection and local venous thrombosis appear to be the predominant factors causing tissue destruction

• Chronic ulceration of pressure points and sites of minor injury. Skin perfusion is otherwise adequate

• Extensive spreading skin necrosis originating in an ulcer and caused by superficial or deep infection. This develops very rapidly and spreads proximally, threatening limb and life

• Painless necrosis of individual toes. These first turn blue, then later become black and mummified, and may eventually be shed spontaneously. This usually occurs in mixed neuropathy and atherosclerosis and the management hinges on whether local amputations will heal or whether arterial reconstruction is needed

Management of neuropathic foot complications

Removal of necrotic tissue

Surgery may involve anything from simple desloughing of an ulcer to major amputation (see Fig. 41.9). If performed correctly, these result in complete and rapid healing. If good foot care is available, amputation of more than single toes is rarely required. Before debridement, arterial inflow must be assessed and the foot revascularised if necessary before debridement or digital amputation to maximise the chances of wound healing.

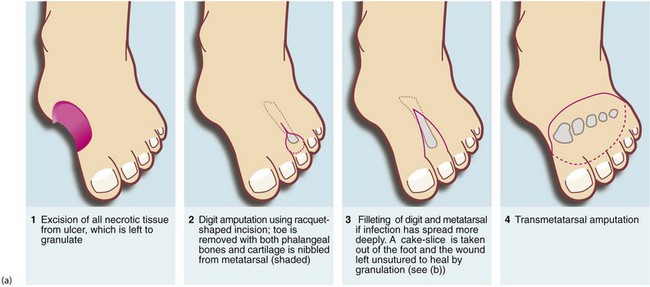

Fig. 41.9 Operations on the diabetic foot

(a) Types of local amputation. (b) This patient had a neuropathic ulcer and necrotic toes but no arterial disease. The second and third metatarsals have been excised, together with all the necrotic tissue, in a ‘cake slice’ procedure. The wound was left open to heal by secondary intention, eventually giving a remarkably good functional result. (c) This elderly man suffered from a combination of neuropathy and obliterative atherosclerosis. He was blind as a result of diabetic retinopathy. The right leg was eventually amputated below knee because of spreading infection, but the left was saved by angioplasty of stenoses in the iliac and superficial femoral arteries, together with local surgery to remove necrotic tissue. Note the typical ‘clawed foot’ and distorted sole of motor neuropathy. Note also that the great toe has already been amputated. The heel has not yet been debrided

Lower limb amputation

Level of amputation

Two principles guide the level of amputation (see Fig. 41.10):

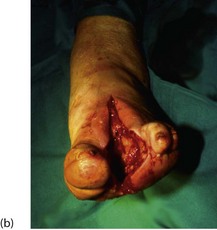

Fig. 41.10 Lower limb amputations

(a) Sites of election for lower limb amputations. (b) Above-knee stump in a diabetic patient. Unfortunately the original above-knee wound broke down and necrotic muscle had to be excised. The wound was left open and had nearly healed by secondary intention two months later. (c) A well-healed below-knee stump at 6 weeks. The operation used a long posterior muscle flap and equal length ‘skew’ skin flaps. (d) The same patient fitted with a modular below-knee prosthesis retained by a close-fitting socket and a small strap above the knee. Note the urinary catheter. (e) Breakdown of below-knee stump because of inadequate arterial blood supply

• The amputation must be made through healthy tissue. If not, there is a high risk of wound breakdown and chronic ulceration, requiring further amputation at a higher level. When amputation is for (uncorrected) peripheral ischaemia, it is almost always necessary to amputate at mid-tibial level or above to ensure healing

• The choice of amputation level must take into account the fitting of a prosthetic limb. For this purpose, the mid-tibia (below-knee) and lower femoral levels (above-knee) are preferred. If the knee joint can be saved, the functional success of a prosthesis is much better. With improved prostheses, through-knee amputation is possible but healing rates are poor; most surgeons and prosthetists prefer above-knee to through-knee amputation as it has a better healing rate and easier prosthetics

The traditional ‘guillotine’ amputation of the battlefield simply sliced off the limb, leaving the wound to heal by secondary intention. This reduced the risk of fatal gas gangrene or tetanus but the outcome for fitting a prosthetic limb was poor. There have been huge developments in amputation techniques in recent decades, particularly in the use of myoplastic flaps. For below-knee amputations, a long posterior flap of muscle and skin is wrapped forward over the amputated bone and sutured in place. This results in more reliable healing and a suitably shaped and cushioned stump. A variation, the Robinson ‘skew flap’, uses a long posterior muscle flap but equal skin flaps. The healing rate is no better but the stump is better shaped for earlier prosthetic fitting. With these techniques and in experienced hands, 70% or more of below-knee amputations for ischaemia will eventually heal even without revascularisation, preserving the knee joint and allowing reasonable walking. Modern below-knee prostheses are modular in construction and weight is borne mainly on the patellar tendon.