Chapter 8 Management of the Tuberous Breast

Management of the tuberous breast represents perhaps the greatest challenge in all of aesthetic breast surgery as, in its most dramatic form, the preoperative deformity in breast shape can be significant. It is important to remember, however, that at times the condition can also be subtle and yet significantly impact in an adverse way the result obtained after aesthetic breast surgery. To avoid poor results in these types of patients, it is very important to recognize which elements of the deformity are present preoperatively and then develop a sound surgical plan designed effectively to correct the anatomic abnormalities that are present.

Clinical Presentation

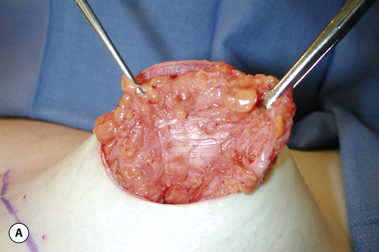

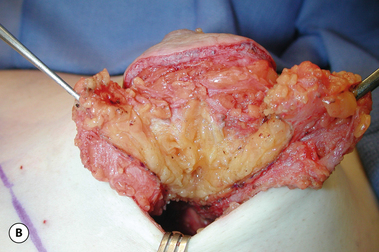

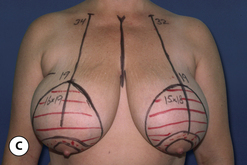

Typically, a fully involved tuberous breast deformity will include a superiorly malpositioned inframammary fold that appears high in relation to what would be considered a ‘normal’ breast position. Present along with this is usually a constricted lower pole skin envelope that is likewise tight and unexpanded. As a result, whatever breast parenchyma is present variably protrudes through the areola, creating a ‘pseudoherniation’. It appears as if the embryonic breast bud was restricted to a small area of the anterior chest wall with an abnormally absent peripheral expansion and, as the breast develops during puberty, it has nowhere to go as it grows except forward. Because the areolar dermis is more elastic than the surrounding breast skin, there is a preferential expansion through the areola, which leads to the herniated appearance (Figure 8.1). Anatomically, in severe tuberous breast cases, fibrous bands can be identified along the underside of the breast in association with the constricted breast base diameter (Figure 8.2 A). Once these bands are cut, the entire breast mound can be observed to expand, creating a more normal breast appearance (Figure 8.2 B). Currently, it is not known if these bands are responsible for the deformity or, conversely, are present as a result of the deformity. Either way, it is interesting to postulate what role these bands might have in the development of the condition.

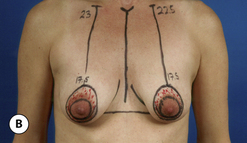

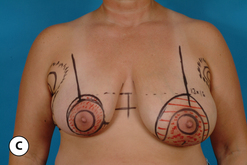

Further complicating the altered overall appearance of the breast is the fact that asymmetry is a very common finding in patients with this condition. At times this asymmetry can be as dramatic a finding as the basic abnormality itself (Figure 8.3). It is not at all uncommon for one breast to present as a hypoplastic, misshapen mound that contrasts starkly with an enlarged, ptotic and disproportionate opposite breast with a nipple–areola complex (NAC) that appears to be medially translocated. Clearly, adequate surgical treatment must be geared toward artistically reshaping both breasts to maximal advantage in an attempt to restore symmetry.

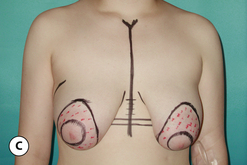

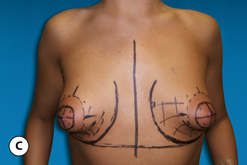

Additionally, the tuberous breast deformity is not an all or none entity and, for any given patient, there can be varying degrees of involvement. As a result, the appearance of the breast can range from a subtle tightening of the inframammary fold all the way to the fully developed deformity with asymmetry as described previously (Figure 8.4). All of these factors combine to make treatment of the tuberous breast one of the most demanding surgical challenges in all of aesthetic breast surgery.

Surgical Strategies

Management of the Constricted Skin Envelope

It must be emphasized that, even in patients who demonstrate only a mild tendency toward a tuberous breast, the inframammary fold contour can create significant problems in breast shaping. This can become very important in a general breast augmentation practice as the subtly high and mildly tight inframammary fold can escape the notice of the surgeon, only to become a problem later at the time of surgery when the lower pole of the breast appears constricted or the previous fold fails to soften completely as a new and lower fold position is created. These types of patients can be recognized by carefully observing the nature of the medial inframammary fold crease. If there is any convexity or superiorly oriented curving of the medial lower pole contour, a mild tuberous breast can be diagnosed (Figure 8.5). Recognition of this deformity preoperatively can help prepare the surgeon for what is to come at the time of surgery and allow for appropriate preoperative technical planning to be done. Also, the patient can be advised ahead of time as to the nature of her deformity, which then allows reasonable expectations to be set.

Perhaps the most difficult determination that must be made by the surgeon is whether or not the constricted inferior pole skin can be expanded enough to allow the primary placement of a breast implant to create a natural contour in the lower pole of the breast. Also, it must be determined whether or not the crease created by the old inframammary fold (IMF) can be overcome by the implant once the new and more inferiorly located fold is created. This is a critical decision point in designing a successful operative strategy as, in fully developed tuberous breast cases, a persistent fold and a flattened and tight lower pole contour will very commonly persist despite aggressive release of the underlying soft tissue support structures. In these patients, better control of the lower pole and the location of the IMF can be afforded with the primary use of a tissue expander. In this fashion, the constricted skin envelope can be stretched sufficiently over time to allow the subsequent placement of an implant and any persistent crease in the old IMF can be softened. Deciding between the primary insertion of an implant versus the use of a staged tissue expander/implant strategy is the major determination that must be made when treating a patient with a tuberous breast deformity. This decision is complicated by other factors. To a certain extent, an old IMF crease that does not completely soften initially may subsequently relax over time due to the influence of the underlying implant. When this old fold will fill out and to what extent will be very patient dependent and is therefore subject to a significant degree of variability. As a result, an early persistent fold that can detract from the overall result after surgical correction may or may not improve over time and in no way can this be predicted with certainty. Added to this is the desire on the part of many patients to accomplish surgical correction in one operation. Besides the basic advantages of needing only one operation on traditional considerations such as operative risk, recovery and time off work, many patients have a financial incentive to effect correction in one stage. Unfortunately, insurance companies very commonly do not extend benefit coverage for tuberous breast correction and the procedure is considered cosmetic. As a result, a great many patients have financial constraints that allow only one procedure. All of this combines to place a fair amount of pressure on the surgeon to provide a one-stage correction.

To this end, several surgical strategies can be employed to maximally expand the skin of the lower pole and accurately lower the IMF. By placing the implant in the subglandular plane, direct force is applied to the skin of the lower pole and any tethering effect created by the pectoralis major muscle can be obviated. Also, by using the subglandular plane, the underside of the breast can be stretched and released as needed. As noted previously, there may be tethering fascial bands running horizontally along the underside of the breast. By radially scoring up into the parenchyma and dividing these bands, a visual and palpable release of the underside of the breast will be noted, resulting in a softer and more compliant breast mound. Taken together, these two maneuvers will allow the soft tissue envelope and the implant to better complement one another, resulting in a smooth and naturally contoured lower pole.

Management of Breast Asymmetry

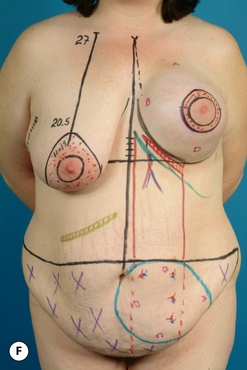

When a symmetric tuberous breast deformity is present, the same operative techniques are simply applied from side to side as needed to provide a symmetric result. However, it is very common for the breasts to demonstrate asymmetrically variable deformity in shape and size. One common variant of this clinical presentation is the patient who presents with a fully developed hypoplastic tuberous breast on one side and an enlarged and ptotic breast on the other. It is important to realize that the enlarged breast almost invariably demonstrates many of the attributes of a tuberous breast including a superiorly dislocated IMF and a constricted base diameter. Very often, the breast protrudes over the IMF, creating an exaggerated ptosis with an enlarged areola that tends to be displaced medially. Adequate treatment to provide for a symmetric result must then concentrate not only on the frankly tuberous hypoplastic breast, but the enlarged and ptotic breast as well. From a surgical planning perspective, it is my preference to either reduce or lift the enlarged breast at the same time as the hypoplastic breast is treated with an implant in the hopes of providing the best symmetry possible in one stage. Should a revision subsequently be required, the breasts will display a greater degree of symmetry than they did initially and the revision will be easier to accomplish with greater accuracy.

Clinical Applications

Soft Tissue Reconstruction

In some patients with a fully developed tuberous breast deformity, there may be enough tissue to allow the breast simply to be re-sculpted without the need for an implant. In these cases, it is possible to utilize a standard mastopexy technique to reshape the breast and lift and reposition the NAC. However, a technique that manages only the skin envelope will not adequately address the deformity as internal dissection and release of the constricted breast base is required to allow the breast to splay out and more anatomically fill out the skin brassiere. My preferred method for doing this is with the short scar periareolar inferior pedicle (SPAIR) technique. Because of the way the breast flaps are developed, an internal release of the constricted base is accomplished that allows the normal dimensions of the breast to be restored. Then, after the inferior pedicle is developed, the underside base of the pedicle can be scored to release completely any deep restraining bands that may be present. Once the breast is reshaped and the widened areola reduced, a standard circumvertical pattern is applied to normalize the skin envelope (Figure 8.6). This same strategy can be used in patients with a tuberous breast deformity that includes any degree of macromastia as a reduction in breast volume can easily be accomplished along with the associated soft tissue release and reshaping of the breast. As with more standard techniques of breast reduction, the advantage of using the SPAIR technique is that an effective method for reshaping the breast and reducing the volume is provided that results in only a circumvertical scar pattern with the inframammary fold scar being eliminated. Because the technique is associated with only a modest settling during the postoperative recovery period, the classical finding of ‘bottoming out’ associated with the Wise pattern inferior pedicle technique is negated and the shape of the breast does not significantly change over time (Figure 8.7). This, along with the fact that the technique can be applied to a wide variety of breast sizes and shapes makes it particularly applicable to the subset of tuberous breast patients who present with asymmetric macromastia (Figure 8.8). Because the shape of the breast is aesthetic immediately, no provision for trying to predict how the breast shape will change over time is required, therefore the breasts can be sculpted with confidence at the initial procedure and very aesthetic results can be obtained.

Implant Based Reconstruction

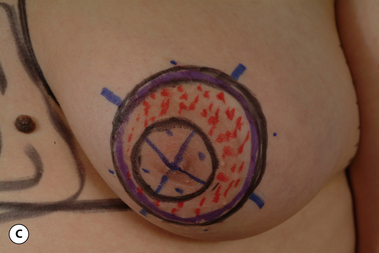

If there is not enough native breast parenchyma to adequately fill out the skin envelope after it has been released, then additional volume must be provided for in the form of an implant. After it has been determined that the soft tissue envelope of the hypoplastic constricted breast is compliant enough to accept a breast implant, planning for the placement of the implant proceeds as it does for any breast augmentation. The three major decisions that must be made, namely implant choice, incision location and pocket selection, are made based on the dictates of the clinical situation. As noted previously, the subglandular plane can afford a practical advantage to shaping the breast in most patients as the skin envelope is more directly filled out by the implant when it is placed on top of the pectoralis major muscle rather than underneath it. In this fashion, any potential tethering effect of the muscle is obviated and the implant can fill out the skin envelope unimpeded by any potential internal constriction. Also, the incision location is optimally situated at either the IMF or around the areola. If there is any degree of areolar herniation or enlargement, a periareolar approach is best used to access the subglandular plane as this will also allow the altered areolar dynamics to be addressed as discussed previously (Figure 8.9). If the areola is not enlarged or does not need repositioning, the IMF incision can provide a direct approach to the underside of the breast and allow soft tissue release and implant insertion (Figures 8.10, 8.11). The transaxillary approach is the least favored approach as direct visualization of the altered and constricted elements of the soft tissue envelope can be difficult at best, even with endoscopic control, and subglandular placement of the implant may be difficult to accomplish through this incision. Finally, implant selection proceeds as with a standard breast augmentation. Essentially, any type of implant can provide an aesthetic result given the types of considerations discussed in the chapter on breast augmentation.

Tissue Expander Based Reconstruction

In cases where it has been determined that an implant will be required to provide the needed volume in the affected breast, but the soft tissue envelope is too constricted to allow the primary placement of an implant, a tissue expander must then be used to prepare the pocket. The same types of considerations that influence decision making for implant placement also come into play when using a tissue expander. Namely, the optimal plane for insertion of the device is the subglandular plane and the most versatile incision location is periareolar. The only important variable influencing the expander choice relates to the base diameter of the device. It is important to completely fill out the width of the tuberous breast to be certain an appropriate implant can ultimately be inserted into the pocket. For this reason, the same types of considerations that are used in the breast augmentation implant selection are employed in choosing an expander. Essentially, the base diameter of the desired breast is measured and an estimate is made of the medial and lateral soft tissue contribution to this measurement. By subtracting half of the medial and lateral pinch thickness, a starting width for the expander can be determined. It is my preference to choose a base diameter that slightly exceeds this measurement by up to a centimeter as it is much more preferable to have a larger pocket at the time of expander exchange for the implant than a pocket that is not wide enough. Selecting the height of the expander is dependent on surgeon preference. In some cases, it can be advantageous to use a full-height device to ensure that every last portion of the pocket is stretched to make room for the subsequent implant. Candidates for this strategy include those patients who present with a soft tissue envelope that is severely constricted in all directions. Alternatively, it can also be advantageous to use a mid-height device to focus expansion on a tight lower pole. This strategy will limit the magnitude of the deformity created during the expansion process and may be more applicable in those patients in whom the expander will remain in place for 6 months to a year or more.

At times it can be advantageous to plan a long-term expansion process, leaving the expander in place for a year or more. Candidates for this strategy include young girls in their mid- to late teens who present with a tuberous breast on one side and an immature and incompletely developed breast on the other. In such cases, initial reconstruction of the tuberous breast may provide short-term symmetry; however, once the opposite breast reaches full maturity and changes in the size, shape or volume of the breast occur, the symmetry may be lost and a revisionary procedure later in life may become necessary. It can be a better option to insert an expander once the deformity begins to result in a noticeable breast asymmetry and then simply keep the expander in place for up to several years, occasionally inflating the device as needed to keep up with the growth of the opposite breast. Once breast growth appears to have stabilized, the expander can be removed and replaced with an appropriately sized permanent implant (Figure 8.12).

At the time of expander removal and replacement with the permanent implant, any revisionary procedure required to obtain the best aesthetic result possible can and should be performed. In many instances, such maneuvers can include partial or complete capsulectomy, raising or lowering the inframammary fold, recontouring the lateral chest wall via liposuction, or redoing a mastopexy to create symmetry in the location of the NAC (Figure 8.13). It is for this reason that my personal approach utilizes two distinct devices each managed at a separate operative procedure. This is in contrast to the use of combination expander/implant devices constructed of an internal saline bladder surrounded by an outer silicone gel envelope of varying thickness and volume. The inner bladder is connected to a remote valve via a silicone rubber tube that passes through the outer silicone gel layer. Once the device is inserted and subsequently inflated to the desired volume, the valve and the tubing can be removed from the device by pulling the tubing free from a self-sealing sheath that passes through the implant. This procedure is performed under local anesthesia and involves a small incision located over the location of the remote valve. The advantage of this approach is that only one general anesthetic is required to complete the procedure as the valve removal is easily performed in the office. Also, only one device is required, which can help hold down costs for patients who do not qualify for insurance coverage. The disadvantage is that the dimensions of the expander/implant are fixed and, since the device by default also functions as the permanent implant, any design feature of the device regarding base diameter or projection that does not create the desired result cannot be changed. Also, strict utilization of the expander/implant ‘one-stage’ strategy eliminates the opportunity to revise the soft tissue envelope at the second-stage procedure and can prevent the surgeon from achieving the best result possible. Therefore, although some authors have been able to utilize such combination expander/implant devices to good effect, greater versatility is afforded when the surgeon has the freedom to alter the soft tissue dynamics at a second procedure where the expander is removed and a carefully chosen permanent implant is inserted. In this fashion, strict control over all the variables that combine to determine the quality of the final result is maintained and the surgeon is not locked into the dimensions of the initial expander in terms of base diameter, shape, or projection.

No matter what the specifics of the expansion strategy may be, the basic design of the expansion approach remains sound and the opportunity to expand the soft tissue envelope over time can greatly enhance the ability of the surgeon to reshape the breast, reposition the inframammary fold and aesthetically reconstruct the size and shape of the resulting breast with a properly chosen permanent implant. By using this staged approach, consistent and aesthetic results can be obtained.