CHAPTER 26 Management of Superior Sagittal Sinus Invasion in Parasagittal Meningiomas

Resection Versus Irradiation

INTRODUCTION

Treatment of meningiomas that invade vital vascular structures is still a significant challenge in neurosurgery.1 Invasion of the superior sagittal sinus (SSS) is commonly observed in parasagittal meningiomas; it increases the risk of recurrence, and, in certain cases, the management of the venous sinus invasion becomes a greater problem than the resection of the tumor.1,2 Current treatment options vary according to the involved segment and to the extent of invasion; however, many unresolved problems remain.

PARASAGITTAL MENINGIOMAS AND THE SUPERIOR SAGITTAL SINUS

Parasagittal meningiomas comprise 21% to 31% of intracranial meningiomas.3–5 The distribution of the meningiomas along the SSS ranged from 14.8% to 33.9% in the anterior third, from 44.8% to 70.4% in the middle third, and from 9.2% to 29.6% in the posterior third of the sinus.6 As shown by several studies the recurrence rate of meningiomas depends on the completeness of resection.3,7–9 Therefore, the aim of surgery in parasagittal meningiomas is complete surgical resection of the tumor along with the involved dura and bone with minimal morbidity and possibly supplement this with adjuvant therapies to decrease the chance of recurrence. This is a major challenge if the tumor has invaded the SSS, because damage to the venous drainage of the brain can result in permanent neurologic damage.

The extent of venous involvement by the meningioma can range from invasion of the outer surface of the venous wall to complete invasion and obliteration of the sinus. Several authors have devised classification schemes for surgical decision making.1,10,11 The first detailed classification scheme of Krause was later modified by Merrem,11 then Bonnal and Brotchi.10 The latest, simplified version by Sindou1 describes 6 types of parasagittal meningiomas according to the degree of sinus invasion:1

The reported incidences of these types are 31%, 8%, 11%, 13%, 5%, and 32%, respectively.2

The superior sagittal sinus drains the superficial veins of both cerebral hemispheres. The sinus increases in size from anterior to posterior and is divided into anterior, middle, and posterior thirds.1 The clinical consequences differ from one region to the other. It is widely cited that the sacrifice of the anterior third is well tolerated. However, even when its rarely encountered, general slowing of the thought process and activity or even akinetic mutism may complicate such a resection.1 The middle third receives the central group of cortical veins and its sacrifice carries the risk of hemiplegia and akinesia.1 The posterior third is the largest portion, which receives the straight sinus. Acute occlusion or surgical sacrifice of the posterior third carries a significant risk of fatal brain edema and increase in intracranial pressure (ICP).

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Parasagittal meningiomas located in the middle third portion of the superior sagittal sinus are the most difficult to treat. This is caused by the abundance of afferent veins, the significant morbidity associated with this location, and the high risk of recurrence. For meningiomas that totally obstruct the SSS, total excision of the tumor and the obstructed part of the sinus is traditionally considered to be the treatment of choice. However, there are reports that challenge this belief. Some studies indicated that replacement or bypass of the sagittal sinus by using a vein graft may be useful and result in reduced morbidity and mortality, as compared with radical excision including the occluded sinus without venous reconstruction.2 Sindou and colleagues reported their results in 15 patients who had complete occlusion of the SSS by the tumor and who were treated with global resection of both the tumor and the invaded sinus: 3 (20%) of the patients died and 6 (40%) had permanent neurological morbidity. In contrast, only 1 (7.7%) of the 13 patients who had a venous reconstruction after global resection of both the tumor and the invaded sinus suffered permanent neurologic morbidity. The authors explained this unexpected finding with the possibility that veins running in the capsule or inside the tumor might provide some degree of continual flow between the proximal and distal aspects of the occluded sinus.2

The significant challenge lies in the management of patients with patent SSS. In such cases surgical resection of the meningioma along with the infiltrated but patent SSS carries a significant risk of mortality and morbidity.12–15 Certainly, at least the bulk of the tumor should be removed whenever possible when the patient is progressively symptomatic; however, there is no clear consensus on how aggressive the surgeon should manage the part that invades the sinus. Two surgical strategies exist for the management of an infiltrated but patent SSS: (1) maximal safe tumor resection outside the involved sinus and (2) aggressive surgical resection of the involved portion with subsequent venous reconstruction.

Colli and colleagues6 reviewed their 53 patients with parasagittal meningiomas. In 7 cases, the tumor involved and partially obstructed the SSS. They removed the tumor subtotally and did not attempt sinus resection or reconstruction. They found that the recurrence-free survival rate was not related to extent of resection. Caroli and colleagues16 reported surgical results for 328 cases of parasagittal meningiomas. Their strategy involved resection of the SSS if it was obliterated by the tumor and to preserve if it was not obliterated. This study included 221 patients with meningiomas involving the middle or posterior third of the SSS. The recurrence rate was 3% in Simpson grade 1 resections, 35% in Simpson grade 2 resections with sinus completely resected cases, and 8% in Simpson grade 3 with sinus marginally resected cases.

Recurrence in limited resections and the risk of serious morbidity and mortality after sacrificing a patent sinus prompted surgeons to develop techniques for reconstructing the sinus at the time of resection.1,10,14,16–19 Such a venous reconstruction is a formidable surgical challenge and the literature contains only few large case series of SSS reconstruction. In 1978, Bonnal and Brotchi10 reported their results for SSS repair in 34 cases of parasagittal meningioma. Their aim was to preserve SSS patency and they used venous autografts when necessary. In 9 cases, the surgeons were able to preserve the patency of the sinus without using a graft. In the other 25 cases, they removed 1 or more walls of the SSS and then rebuilt the structure using a dural or venous graft. In 1 case, it was necessary to remove the entire SSS and then create a new sinus structure using a total vein graft. Immediate postoperative control angiography demonstrated patent SSS in 87% of the 34 patients. In 2003, Brotchi’s research group documented the long-term results for these cases.10 Of the 25 individuals who underwent partial or total SSS removal and sinus reconstruction, 15 cases were total tumor excisions and these patients had been followed for more than 10 years. Five (33%) of these 15 individuals had developed focal meningioma recurrence. The remaining 10 of the 25 patients underwent subtotal tumor excision, and 8 of them had been followed for more than 10 years. Five (63%) of these 8 patients had developed local recurrence. Based on these outcomes, the authors questioned the efficacy of their approach to these tumors. They concluded that the optimal strategy for meningiomas involving the SSS is gross tumor removal followed by monitoring, and radiosurgery if regrowth occurs.

Hakuba and colleagues20 reported his results with 23 cases of parasagittal meningiomas. In 6 cases he removed the tumor and the sinus totally. In 17 cases, there was a sinus involvement and after total tumor excision he repaired the sinus wall or reconstructed the sinus with a vein graft. In this group, there was 29% of postoperative paresis. Postoperative angiogram demonstrated the patency of SSS in 66% of cases. This means that in one third of the cases the reconstruction of the SSS did not work.

In 2001, Sindou21 reported the outcomes of SSS reconstruction in 32 cases of meningioma infiltrating the SSS. Repair was achieved by patching in 16 cases and by bypass (10 autologous vein grafts, 6 GORE-TEX® grafts) in the other 16 cases. This author advocates that the SSS should be reconstructed even if the cavity has been totally obliterated by the meningioma. He reasons that it is difficult to safely remove a totally obliterated SSS without performing reconstruction because collateral venous pathways must often be sacrificed during the surgical approach. Concerning patch material, Sindou reported success with locally harvested dura, fascia lata, fascia temporalis, or pericranium. For cases that require bypass, he recommends autologous vein grafts. Sindou claims that graft thrombosis in the long term has no effect on the neurologic status of patients who had bypass. He states that this is because gradual occlusion of the SSS by meningioma growth allows time for compensatory venous pathways to form. Control angiography was done in 28 of the 32 cases reported by Sindou. Thirteen of the 16 patients who underwent sinus repair via patching were assessed in this manner, and angiography showed sinus occlusion in only 1 of these individuals during follow-up. Nine of the 10 patients who received autologous vein grafts for bypass were assessed with angiography 2 weeks after the operation. At this stage, 3 of these 9 grafts had thrombosed but the patients showed no clinical deterioration. As detailed, the other 6 bypass patients received GORE-TEX® grafts. All of these were evaluated angiographically, and all thrombosed within the first week. Thus, of the 28 total repaired SSS that were assessed angiographically after surgery, 10 (36%) were occluded. These results raise questions about the efficacy of sinus reconstruction in cases of meningioma invading the SSS. In addition to the 32 SSS meningioma cases that involved sinus repair, Sindou also reported on 40 other SSS meningioma cases who did not require sinus reconstruction. Only 2 of his 72 total patients died, and neither of these individuals had undergone SSS reconstruction. For the 72 total patients in his series, the rate of morbidity was 10%, the mean follow-up time was 8 years, and the rate of meningioma recurrence was 2.5%.

A more recent paper by DiMeco and colleagues14 reported the authors’ extensive surgical experience with meningiomas involving the SSS. In 100 of the 108 total cases, they were able to achieve Simpson grade 1 or 2 removal. These authors advocate resecting the tumor mass plus any SSS tissue that is infiltrated by tumor, and then repairing the sinus wall(s) using lyophilized cadaveric grafts. In cases where the SSS is totally occluded, they excise the entire tumor and the entire sinus. Thirty (28%) of their 108 cases featured tumoral invasion of the whole SSS, and these patients underwent excision of the tumor plus the complete sinus. The other 78 tumors had only partially invaded the sinus. Tumor resection was performed in these cases, with Simpson grade 1 and 2 removal achieved in 40 and 34 patients, respectively. Simpson grade 4 resection was performed in the remaining 4 cases. DiMeco and colleagues14 did not perform bypass surgery in this series of 108 cases of meningioma invading the SSS. They reported only 2 deaths (1.9% mortality). The most serious complication was brain edema, which occurred in 8.3% of the 108 cases. The authors did not perform postoperative angiography, so the sinus patency rate for this series is unknown. The mean follow-up time was 79.5 months, and the recurrence rate was 13.9%.

Sindou reported his experience with aggressive management of parasagittal meningiomas invading the superior sagittal sinus twice.2,21 The second study, which involved 100 meningiomas with invasion of dural sinuses, included 92 cases that were located in the SSS (30.4% in the anterior third in close relation to the precentral veins, 52.3% in the middle third in relation to the postcentral veins, and 17.4% in the posterior third).2 The authors reported gross total removal in 93% of the patients (Simpson grade 1 or 2) and radical excision combined with coagulation of a small amount of residual tumor (Simpson grade 3 removal) in the other 7%. The permanent neurologic morbidity rate was 8%, and the mortality rate was 3%. The authors reported a recurrence rate of 4% over a mean 8-year follow-up period (3–23 years). The study had one very important conclusion, as mentioned earlier: resection of a totally occluded sinus was associated with significant morbidity.

Aside from the series presented in the preceding text, the literature contains few sporadic case reports on SSS reconstruction for parasagittal meningiomas. One report by Steiger and colleagues22 documents a case of SSS meningioma in which sinus reconstruction was achieved with venous interposition grafting and reimplantation of rolandic veins. Two weeks after surgery, Doppler sonography confirmed that the SSS was patent. Angiography was performed in this case. Computed tomography (CT) at 20 months revealed no recurrence, but no long-term findings were available. In another case of meningioma infiltrating the SSS, Murata and colleagues23 performed cortical vein anastomosis. Control angiography at 2 weeks after surgery revealed a patent sinus and patent cortical veins, but the long-term outcome for this patient was not documented.

A newer and less invasive mode of management for an occluded sinus is endovascular stent placement. Ganesan and colleagues24 reported a patient with benign intracranial hypertension due to parasagittal meningioma–related sinus obstruction. The authors treated this patient with endovascular stent placement and adjuvant radiotherapy. Fourteen months after the treatment the stent was patent and the tumor was stable. Higgins and colleagues25 reported treatment of a patient with tentorial meningioma who was operated three times and had received radiotherapy. Increased ICP due to partial obstruction of the confluence of sinuses was successfully treated with a stent placement into the right transverse sinus. At the 9-month follow-up post-stenting the patient was reportedly well.

ROLE OF RADIOSURGERY

The high rate of complication rates of aggressive treatment strategies and the risk of recurrence after conservative treatment have created a need for alternative treatment strategies. Radiosurgical treatment of meningiomas has proven safe and effective, and this treatment modality for meningiomas has become very popular in recent years for primary treatment of small meningiomas or as an adjuvant for residual or recurrent cases.26,27 The reported tumor growth control rates range from 85% to 95%.27 As in the case of cavernous sinus meningiomas, this relatively less invasive treatment modality can potentially be used as an adjunct or alternative in parasagittal meningiomas invading the SSS to achieve long-term tumor growth control with little morbidity.28

Currently there is no definitive evidence to show superiority of aggressive or less invasive treatment paradigms. Only two studies have been published to test the hypothesis that the Gamma-Knife can be effectively used in the treatment of parasagittal meningiomas with SSS invasion. The multicenter study led by Kondziolka and colleagues15 analyzed treatment results in 203 meningiomas with SSS invasion that were treated with gamma-knife radiosurgery. Most of these meningiomas had invaded the middle or posterior region of the SSS and were relatively small tumors (mean tumor volume 10 cm3). Seventy-eight patients underwent radiosurgery as the primary therapy, and the 5-year actuarial tumor control rate for this group was 93%. None of the tumors smaller than 7.5 mL that were treated with radiosurgery showed tumor regrowth in the long term. For the 125 patients who had undergone surgery before Gamma-Knife treatment, the 5-year control rate was only 60%. The authors reported that most cases of radiosurgery failure were due to remote tumor growth. Defining meningioma borders for radiosurgery can be difficult in patients who have undergone previous surgery for SSS-invading meningiomas. In the 203 cases reported by Kondziolka and colleagues, the median marginal dose was 15 Gy. Sixteen percent of the patients developed symptomatic edema after radiosurgery, and this rate is relatively high. The authors analyzed potential contributors to edema development and found that the only factor correlated with this complication was previous neurologic deficit. In all cases, the edema resolved with medical therapy. Kondziolka and colleagues concluded that, in cases where a small meningioma (< 3 cm diameter) has invaded the SSS and the sinus is still patent, radiosurgery should be the primary surgical procedure. In cases where the tumor is larger, they recommend planned, second-stage radiosurgery.

AUTHORS’ EXPERIENCE

We treated 60 cases with SSS infiltrating meningiomas between 1997 and 2007. The results of the first 43 cases were previously reported.29 The follow-up period after radiosurgery ranged from 12 to 96 months (median, 36 months) in 49 patients. The group consisted of 16 men and 33 women with a mean age of 56 years (range, 9–87 years). The meningioma was mainly located in the anterior third of the SSS in 7 cases (12%), in the middle third in 32 cases (70%), and in the posterior third in 10 cases (19%). Thirty-nine patients were clinically symptomatic at the time of Gamma-Knife treatment. The other 10 were asymptomatic but were treated after serial MRI scans revealed progression of the meningioma. Nineteen of the 49 patients had virgin tumors (group I), whereas the other 30 had undergone previous resection in our center (group II). At our institution, MRI is performed within the first 24 hours after tumor resection, and this reveals the presence and extent of any residual tumor. Based on these findings, we divided the group II (previously operated) cases into subgroups. Of the 30 patients in that group, 12 had residual tumors (group IIA) and 18 had recurrent tumors (group IIB).

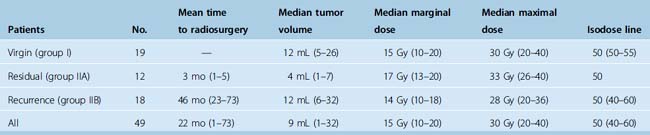

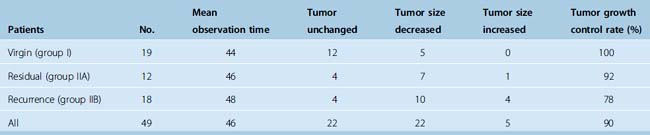

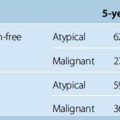

Table 26-1 lists the tumor size and radiosurgical treatment information for the three groups investigated and for the 49 tumors overall. The median tumor volume in the 49 patients was 9 mL (range, 1–32 mL). In most cases, a 50% isodose was administered to the tumor margins. The median marginal dose was 15 Gy.

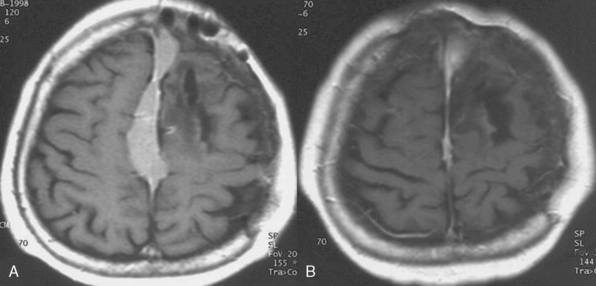

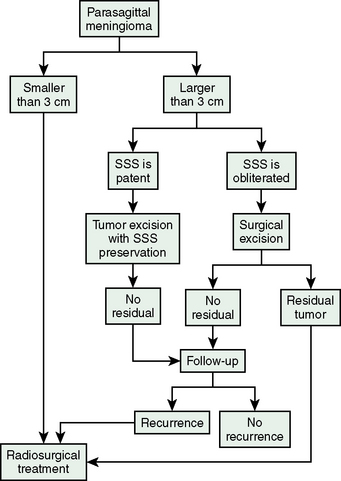

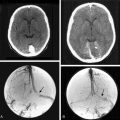

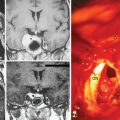

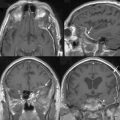

Table 26-2 lists the radiologic results by group and for all patients combined. For total of 49 cases, follow-up time after radiosurgery ranged from 12 to 104 months (median 58 months). During follow-up, 22 (45%) tumors decreased in size, 22 (45%) remained unchanged, and 5 (10%) expanded. The overall rate of tumor control with radiosurgery was 90%. In our series, 30 of the 49 patients had undergone surgery before Gamma-Knife treatment. Based on at least 1 year of follow-up, radiosurgery provided successful tumor control in 14 of the 18 patients with meningioma recurrence and 11 of the 12 patients with residual tumor tissue. This discrepancy is related to low tumor volumes in the residual tumor cases, which meant that high marginal doses could be applied to these neoplasms. Our 2 years of follow-up data also indicate that gamma-knife therapy provided 100% tumor control for the 19 patients who had virgin meningiomas affecting the SSS. Much longer follow-ups are needed for definitive conclusion on this issue. We found that radiosurgery was ineffective for our two cases of malignant meningioma invading the SSS, and do not recommend Gamma-Knife as a primary irradiation treatment for malignant meningiomas in this location. Four of the five tumors that progressed after radiosurgery were recurrent meningiomas and 1 was a residual meningioma. The five included both malignant meningiomas, one of the two atypical meningiomas, and two typical meningiomas in group II. The overall rate of recurrence after radiosurgery for the 24 residual or recurrent typical meningiomas we treated with Gamma-Knife surgery was 8%, which is comparable to reported recurrence rates for gross total resection (Fig. 26-1). Based on this experience we developed an algorithm for the treatment of SSS infiltrating meningiomas (Fig. 26-2).

[1] Sindou M., Auque J. The intracranial venous system as a neurosurgeon’s perspective. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 2000;26:131-216.

[2] Sindou M.P., Alvernia J.E. Results of attempted radical tumor removal and venous repair in 100 consecutive meningiomas involving the major dural sinuses. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:514-525.

[3] Chan R.C., Thompson G.B. Morbidity, mortality, and quality of life following surgery for intracranial meningiomas. A retrospective study in 257 cases. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:52-60.

[4] Jaaskelainen J. Seemingly complete removal of histologically benign intracranial meningioma: late recurrence rate and factors predicting recurrence in 657 patients. A multivariate analysis. Surg Neurol. 1986;26:461-469.

[5] Kallio M., Sankila R., Hakulinen T., Jaaskelainen J. Factors affecting operative and excess long-term mortality in 935 patients with intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:2-12.

[6] Colli B.O., Carlotti C.G.Jr, Assirati J.A.Jr, et al. Parasagittal meningiomas: follow-up review. Surg Neurol. 2006;66(Suppl. 3):S20-S27. discussion S27–8

[7] Simpson D. Recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:22-39.

[8] Mirimanoff R.O., Dosoretz D.E., Linggood R.M., et al. Meningioma: analysis of recurrence and progression following neurosurgical resection. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:18-24.

[9] Marks S.M., Whitwell H.L., Lye R.H. Recurrence of meningiomas after operation. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:436-440.

[10] Bonnal J., Brotchi J. Surgery of the superior sagittal sinus in parasagittal meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:935-945.

[11] Merrem G. [Parasaggital meningiomas. Fedor Krause memorial lecture]. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1970;23:203-216.

[12] Stippler M., Kondziolka D. Skull base meningiomas: Is there a place for microsurgery? Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005;148:1-3.

[13] Iwai Y., Yamanaka K., Morikawa T. Adjuvant gamma knife radiosurgery after meningioma resection. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:715-718.

[14] DiMeco F., Li K.W., Casali C., et al. Meningiomas invading the superior sagittal sinus: surgical experience in 108 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:1263-1272. discussion 1272–4

[15] Kondziolka D., Flickinger J.C., Perez B. Judicious resection and/or radiosurgery for parasagittal meningiomas: outcomes from a multicenter review. Gamma Knife Meningioma Study Group. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:405-413. discussion 413–4

[16] Caroli E., Orlando E.R., Mastronardi L., Ferrante L. Meningiomas infiltrating the superior sagittal sinus: surgical considerations of 328 cases. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:236-241.

[17] Hakuba A. Al-Mefty O., editor. Reconstruction of dural sinus involved in meningiomas, Meningiomas. Raven Press, New York, 1991;371-382.

[18] Hancq S., Baleriaux D., Brotchi J. Surgical treatment of parasagittal meningiomas. Sem Neurosurgery. 2003;3:203-210.

[19] Buster W.P., Rodas R.A., Fenstermaker R.A., Kattner K.A. Major venous sinus resection in the surgical treatment of recurrent aggressive dural based tumors. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:522-530.

[20] Hakuba A., Huh C.W., Tsujikawa S., Nishimura S. Total removal of a parasagittal meningioma of the posterior third of the sagittal sinus and its repair by autogenous vein graft. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1979;51:379-382.

[21] Sindou M. Meningiomas invading the sagittal or transverse sinuses, resection with venous reconstruction. J Clin Neurosci. 2001;8(Suppl. 1):8-11.

[22] Steiger H.J., Reulen H.J., Huber P., Boll J. Radical resection of superior sagittal sinus meningioma with venous interposition graft and reimplantation of the rolandic veins. Case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1989;100:108-111.

[23] Murata J., Sawamura Y., Saito H., Abe H. Resection of a recurrent parasagittal meningioma with cortical vein anastomosis: technical note. Surg Neurol. 1997;48:592-595. discussion 595–7

[24] Ganesan D., Higgins J.N., Harrower T., et al. Stent placement for management of a small parasagittal meningioma. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:377-381.

[25] Higgins J.N., Burnet N.G., Schwindack C.F., Waters A. Severe brain edema caused by a meningioma obstructing cerebral venous outflow and treated with venous sinus stenting. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:372-376.

[26] Kondziolka D., Lunsford L.D., Coffey R.J., Flickinger J.C. Gamma knife radiosurgery of meningiomas. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1991;57:11-21.

[27] Kondziolka D., Mathieu D., Lunsford L.D., et al. Radiosurgery as definitive management of intracranial meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:53-58. discussion 58–60

[28] Pamir M.N., Kilic T., Bayrakli F., Peker S. Changing treatment strategy of cavernous sinus meningiomas: experience of a single institution. Surg Neurol. 2005;64(Suppl. 2):S58-66.

[29] Pamir M.N., Peker S., Kilic T., Sengoz M. Efficacy of gamma-knife surgery for treating meningiomas that involve the superior sagittal sinus. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2007;68:73-78.