Chapter 79 Management of Soft Cervical Disc Herniation

Controversies and Complication Avoidance

About 450 years ago, Vesalius described the intervertebral disc.1 It was not until 1928 that Stookey described a number of clinical syndromes resulting from cervical disc protrusions. These protrusions were thought to be neoplasms of notochordal origin and were incorrectly identified as chondromas.2 During this same era, other investigators provided a more precise understanding of the pathophysiology of intervertebral disc herniation.3–5

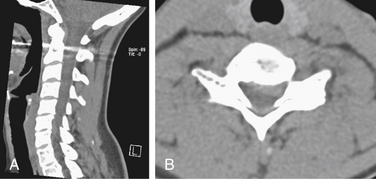

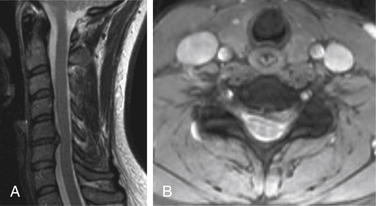

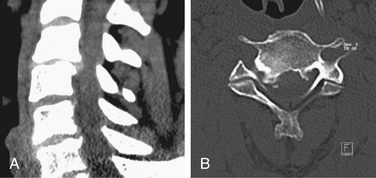

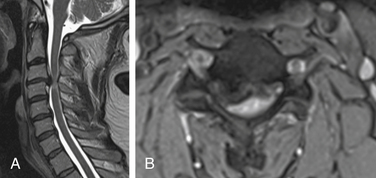

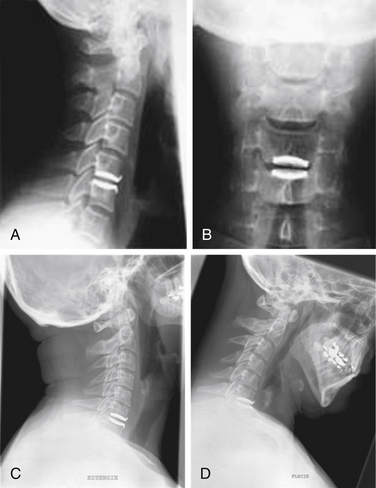

Both soft and hard cervical disc herniations can lead to nerve root compression (radiculopathy) and/or compression of the spinal cord (myelopathy). Hard cervical disc herniation is a condition in which osteophytosis is involved. This chapter focuses on pure soft disc herniation, which causes radiculopathy more frequently than myelopathy (Figs. 79-1 to 79-4).

Population-based data from Rochester, Minnesota, indicate that cervical radiculopathy has an annual incidence rate of 107.3 per 100,000 for men and 63.5 per 100,000 for women, with a peak at 50 to 54 years of age. A history of physical exertion or trauma preceded the onset of symptoms in only 15% of cases. A study from Sicily reported a prevalence of 3.5 cases per 1000 population.6

The most common cause of cervical radiculopathy (in 70–75% of cases) is foraminal encroachment of the spinal nerve due to a combination of factors, including decreased disc height and degenerative changes of the uncovertebral joints ventrally and the zygoapophyseal joints dorsally (i.e., cervical spondylosis). In contrast to disorders of the lumbar spine, pure herniation of the nucleus pulposus (soft disc herniation) is responsible for only 20% to 25% of cases,7 although the relative proportion of disc herniation in younger people is significantly higher.8 Overall, though, in many cases, there is a combination of some spondylosis with a soft disc herniation. Other causes, including tumors of the cervical spine and spinal infections, are infrequent.6

Controversies

Surgical Indications

Data on the natural history of cervical radiculopathy are limited. In the population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 26% of 561 patients with cervical radiculopathy underwent surgery within 3 months of diagnosis (typically for the combination of radicular pain, sensory loss, and muscle weakness), whereas the remainder were treated medically.6 The natural course of spondylotic and discogenic cervical radiculopathy is generally favorable. In particular, pure soft disc herniations often resolve spontaneously.8

The main objectives of treatment are to relieve pain, to improve neurologic function, and to prevent recurrences. None of the commonly recommended nonsurgical therapies for cervical radiculopathy have been tested in randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Therefore, recommendations are derived largely from case series and anecdotal experiences. The patient’s preferences should be taken into account in the decision-making process. Analgesic agents, including opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, are often used as first-line therapy. Retrospective and prospective cohort studies reported favorable results with interlaminar and transforaminal epidural injections of corticosteroids, with up to 60% of patients experiencing long-term relief of radicular and neck pain and a return to usual activities. However, complications from these injections, although rare, can be serious and include severe neurologic sequelae from spinal cord or brainstem lesions. Given the potential for harm, placebo-controlled trials are needed to assess both the safety and the efficacy of cervical epidural injections. Some investigators advocate the use of short-term immobilization (<2 weeks) with either a hard or a soft collar (either continuously or only at night) to aid in pain control. Cervical traction consists of administering a distracting force to the neck to separate the cervical segments and relieve compression of nerve roots by intervertebral discs. Especially in the absence of night pain, traction therapy may be considered to alleviate pain. Various techniques and durations have been recommended. However, a systematic review stated that no conclusions could be drawn about the efficacy of cervical traction. The same is true for exercise therapy.6

Therefore, in appropriate patients, surgery may effectively relieve otherwise intractable symptoms and signs related to cervical radiculopathy, although there are no data to guide the optimal timing of this intervention. For cervical radiculopathy without evidence of myelopathy, surgery is typically recommended when cervical root compression is visualized on MRI or CT myelography with concordant symptoms and signs of cervical root–related dysfunction and when the pain does not disappear despite nonsurgical treatment for at least 6 to 12 weeks. A progressive, functionally important motor deficit represents a more urgent surgical indication. Surgery is definitely recommended in cases in which imaging shows cervical compression of the spinal cord in combination with clinical evidence of moderate to severe myelopathy.6

As summarized in a Cochrane review, there are only a limited number of good-quality studies comparing surgical and nonsurgical treatments for cervical radiculopathy. In one randomized trial comparing surgical and nonsurgical therapies among 81 patients with radiculopathy alone, the patients in the surgical group had a significantly greater reduction in pain at 3 months than the patients who were assigned to receive physiotherapy or who underwent immobilization in a hard collar. However, at 1 year, there was no difference among the three treatment groups in any of the outcomes measured, including pain, function, and mood.9

Comparing cervical with lumbar (soft) disc herniations, Peul10 pointed out that in the absence of alarming symptoms related to lumbar disc herniations, surgery is optional, depending on the patient’s preference. However, in contrast with lumbar disc herniation, cervical soft disc herniations more frequently justify surgical treatment when refractory radiculopathy is concerned.

Surgical Approach

Multiple surgical approaches to the cervical spinal canal or neural foramina are possible, with associated advantages and disadvantages. Ventral and dorsal options have been described.11

The dorsal exposures have three possible advantages in comparison to the ventral approach: (1) Less surgical effort is required in exposing or decompressing multiple levels; (2) additional fusion with or without instrumentation is often not required; and (3) the procedure does not necessarily stiffen the motion segments involved and therefore does not accelerate spondylotic degeneration at adjacent levels, as is thought to occur after (ventral) fusion procedures. Partial hemilaminectomy, with or without foraminotomy, has become a standard dorsal exposure for laterally located cervical disc herniation.11 Central disc herniations, however, should be approached ventrally.

Technically, the dorsal approach is begun with a small partial hemilaminectomy above and below the level of expected pathology.11 Removing the caudal margin of the rostral lamina laterally and the attached ligamentum flavum allows for identification of the lateral dural margin and the nerve root origin. Although the major exposure is caudal, it is desirable to also expose the rostral border of the nerve root to allow for its complete identification and achieve some space for the minimal mobilization of the nerve root. Often, there is a small amount of space caudal to the nerve root. This space can be enlarged with a curette or a high-speed drill. Venous bleeding is most common with this approach and should be adequately addressed during exposition of the neural structures. Care must also be taken to ensure that one has enough of the nerve root exposed that the motor root is not confused with extruded disc material. After sufficient exposure of the nerve, the surgeon starts to explore for a disc extrusion, from above or beneath the nerve root. If there is a soft disc extrusion, the posterior longitudinal ligament can be incised with a knife, and a bit of pressure on the above posterior longitudinal ligament occasionally causes the fragment to be milked outward beneath the elevated root. Following this, there is often some additional space so that the foramen can be better explored and enlarged if necessary. If there is only a small, hard bony ridge beneath the nerve root, it might not be necessary to remove this. Often, a simple but thorough decompression of the nerve root dorsally into the foramen provides adequate relief of symptoms. After removal of an extruded cervical disc, it is not necessary or advisable to enter the cervical disc space to remove additional degenerated disc material from behind. Usually, visualizing the interspace would require significant root and spinal cord retraction, which in itself could result in nerve root or spinal cord injury. On the other hand, such additional discectomy is not necessary, since the recurrence rate for a cervical disc herniation without entering the disc space is less than 1% in most series.

Half a century has elapsed since the initial description of ventral cervical discectomy by Bailey and Badgley.12 Modifications of this technique were described by Robinson and Smith in 195513 and by Cloward and the group of Dereymaeker and Mulier, both in 1958.14,15 Robinson and Smith described an operation for removal of cervical disc material with replacement by a rectangular bone graft, obtained from the iliac crest, to allow for the development of a cervical fusion.13 With Cloward’s method, the discectomy and fusion were performed by a dowel technique. Although numerous modifications have been developed since the 1950s, the great majority of spine surgeons currently use either the Cloward or the Smith-Robinson technique, primarily for herniations that are located on the midline or mediolaterally.16–25

Radiologic evaluation is crucial in decision making. When the abnormality is central, broad based, and dorsal, a ventral procedure is more likely to achieve decompression. On the other hand, with lateral or foraminal nerve root compression, the simpler dorsal keyhole laminoforaminotomy works well. One may consider that the possible additional decompressive effect due to (slight) distraction of the vertebrae (and thus opening of the neuroforamina) in ventral fusion is not obtained via a dorsal approach. Physicians who advocate either procedure exclusively may not always provide the “best” approach.26

Ventral Approach: Cervical Discectomy without Bone Fusion versus Cervical Discectomy with Bone Fusion versus Prosthesis

Cervical discectomy with bone fusion (ACDF) as has been described by Cloward 14 and Robinson and Smith13 has become a routine surgical procedure. Nevertheless, when autografts from the iliac crest are used, the technique has been associated with donor site morbidity such as pain, infection, hematomas, nerve injury, and iliac crest deformity. Graft and fusion problems at the fusion bed may occur, such as nonunion, graft collapse, or dislodgement.27 In attempts to overcome the graft-related problems, cervical discectomy without bone fusion (ACD) was introduced in 1960 by Hirsch.28 However, ACD has usually been associated with postoperative neck pain, cervical curve deformity (kyphosis), and lower fusion rates (up to 60%). One can consider that the actual aim of ACD is even to avoid fusion. Hospital stay is an important consideration in the recent era of cost consciousness. In some countries, the debate between advocates of ACDF and of ACD is still ongoing. Abd-Alrahman et al.27 concluded that the controversial issue in the management of patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy will continue regarding the choice between ACD and ACDF. Proponents of interbody grafting claim that with ACD, the disc height and the area of the neural foramina at that level will decrease postoperatively, with the potential for persistent symptoms and/or the development of a radiculopathy, and that the kyphosis rate is high. With ACDF, the fusion rate is high, the neck pain is less, the distraction of disc space stretches the ligamentum flavum and reduces its buckling, diminishing the risk for postoperative ongoing or recurrent nerve root compression. Nowadays, ACDF is much more frequently performed than is ACD. ACD should furthermore be limited to patients with a single soft disc without spondylosis.

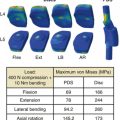

The option of disc arthroplasty is emerging. Cervical disc arthroplasty or total intervertebral disc replacement (TDR) seems to be a promising nonfusion alternative for the treatment of degenerative disc disease, especially in cases of pure soft disc herniation. TDR is designed to preserve motion, avoid limitations of fusion, and allow patients to quickly return to routine activities. The primary goal of the procedure in the cervical spine is to maintain segmental motion after removing the local pathology and, by doing this, to prevent later adjacent-level degeneration,29–31 as is sometimes seen after ACDF due to increased motion stress at those adjacent levels. TDR also avoids the morbidity of bone graft harvest, pseudarthrosis, issues caused by ventral cervical plating, and cervical immobilization side effects.30 The Frenchay (Bristol) prosthesis32 and the Bryan intervertebral disc prosthesis were the first to be clinically assessed in Europe. The first cervical disc arthoplasty clinical trial in the United States was the Bryan disc study initiated in May 2002 after a European prospective human clinical trial began in 2000.33 The results of the European clinical trial with the Bryan disc prosthesis, though neither randomized nor controlled, validated the stability, biocompatibility, and functionality predicted by preclinical testing. Although the mechanical rationale seems obvious and TDR thus can be considered an attractive tool for treating cervical soft disc herniation, Peng-Fei and Yu-Hua34 recently stated that the follow-up time of the studies that have already been published is not (yet) long enough to support the advantage of cervical disc prosthesis technology. On the contrary, Walraevens et al. more recently demonstrated that up to 8 years after surgery with the Bryan disc, maintenance of mobility at the treated level is preserved in the vast majority of cases.35 Moreover, they argued that the prosthesis seems to protect against acceleration of adjacent-level degeneration. Finally, 90% of all patients were shown to have a clinically good to excellent outcome. Chapter 224D provides further details about this matter (Fig. 79-5).

Recently, Yi et al.36 reported that ventral cervical foraminotomy, as cervical arthroplasty, can be a valid treatment for unilateral cervical radiculopathy, sharing the same goal of preservation of segmental motion and avoidance of adjacent segment degeneration.

Cervical Discectomy with Bone Fusion Strategies

Several techniques for ACDF are currently performed, mostly depending on the choice of the surgeon. However, there may be differences in perioperative morbidity and short- and long-term outcome. A recently published study by Bhadra et al.37 analyzed the cost-effectiveness of the three different techniques in comparison to each other and to arthroplasty. Besides a group of arthroplasty patients, they defined three groups of 15 patients each: (1) plate and tricortical autograft; (2) plate, cage, and bone substitute; and (3) cage only. They found that the clinical outcome in terms of a visual analogue scale of neck and arm pain and physical and mental score improvement were comparable with all three techniques. The radiologic fusion rate was comparable to currently available data. Because the hospital stay was longer in the plate and autograft group, the total cost was a maximum with this group. Using a cage alone was the most cost-effective technique in the authors’ hands.

Autograft?

Autograft is still considered the gold standard in achieving radiographic fusion in one-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Autogenous bone has osteoinductive, osteoconductive, and osteogenic properties.38 The capacity for rapid regeneration comes mostly from fresh cancellous bone, which contains bone matrix proteins and mineral collagen. An ideal autograft includes strong cortical bone to provide structural support and cancellous bone for augmented incorporation and fusion characteristics. Revascularization of cancellous bone is completed within 2 weeks, whereas it takes 2 months for cortical bone. An additional advantage of autogenous bone graft is that is does not carry transmissible diseases to the host. Cortical and cancellous graft material is generally obtained from the iliac crest.

As was mentioned by Bhadra et al.,37 autograft as a gold standard is challenged. Seemingly, when rigid instrumentation is used, the inferior fusion rates with allograft can be overcome. Samartzis et al.,39 found that when autograft (without plate) was compared with allograft with rigid ventral plate fixation in one-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, the two methods resulted in statistically equivalently high fusion rates with excellent and good clinical outcomes. The radiographic fusion rate was even higher in the allograft group. They stated also that the use of allograft eliminates complications and pitfalls associated with autologous donor site harvesting. On the other hand, autograft was considered safer in terms of prevention of infection. The specific complication rates related to the plating itself were not addressed. Additionally, the same authors showed in another study 40 that considering autograft in one-level cervical fusion with or without rigid plate fixation, the two methods gave similar results.

Allograft?

Allografts are tissues obtained from cadavers or living donors.38 They are associated with delayed vascularization and delayed incorporation, perhaps because of antigenic recognition. Allografts have osteoinductive and osteoconductive properties. However, they have lost their osteogenic property.

To overcome the relatively high collapse rate of allogeneic iliac crest, Martin et al. conducted a study on the efficacy of allogeneic fibula graft41 on cervical fusion rate. They found that allogeneic fibula is an effective substrate for use in achieving fusion after cervical discectomy. Maximal results were achieved with its use at one level. As a secondary outcome, cigarette smoking appeared to decrease the fusion rates, but not by a statistically significant amount.

Cage?

Cage fusion technology originated in 1979 from Bagby’s work in horses and was first used in humans in around 1990.42 The principle of distraction-compression, the basic principle of stand-alone intervertebral cage fusion, was introduced. Interbody cages provide initial segmental stability by tensioning the ligament apparatus, which anchors a cage’s top and bottom areas to the adjacent end plates. They can be threaded or not.

Titanium cage-assisted ACDF provides long-term stability, increasing lordosis, segmental height, and foraminal height. Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) is a semicrystalline polyaromatic linear polymer that provides a good combination of strength, stiffness, toughness, and environmental resistance. The elastic modulus of the PEEK cage is close to that of bone, which helps to decrease stress shielding and increase bony fusion. The PEEK cage has a deleterious influence on cell attachment and growth and inhibits a stimulatory effect on the protein content of osteoblasts.43 Trabecular Metal is a porous tantalum biomaterial with structure and mechanical properties similar to those of trabecular bone and with proven osteoconductivity.44

Recent studies by Cho et al.45 and by Chou et al.43 consistently showed the equivalence of PEEK cages and autografts in ACDF, in terms of fusion rates, clinical improvement, and complication rate. Löfgren et al. recently published a study in which Trabecular Metal showed a lower fusion rate than the Smith-Robinson technique with autograft after single-level ventral cervical fusion without plating. However, no difference was seen in clinical outcomes between the groups. The operative time was shorter with Trabecular Metal implants.44

To Plate or Not to Plate?

The first question is answered by a number of studies showing higher fusion rates in instrumented autologous and allogeneic grafts, compared with cases without plating, even at one level.46,47 Second, despite the differences in the reported fusion rates of these procedures, they seem to be similar in their effectiveness of symptomatic relief.46,48 The proposal that surgical fusion is unnecessary is controversial.

Bhadra et al.37 tend to answer the final question. Seemingly, plating can compensate for lower fusion rates in allografts in comparison to autografts. The clinical relevance again can be questioned.

Bone Morphogenetic Protein?

Because of the potential risk of pseudarthrosis (0–40%) and late-term destabilization of ventral cervical fusion, means to improve the rate and speed of bone healing seem to be needed. Besides autogenous iliac crest grafts and PEEK cages, BMP containing allograft struts can be considered.49,50 When consideration is given to BMP, necessity, efficacy, safety, and cost should be taken into account. Tumialan et al.51 and Buttermann showed the efficacy of BMP.52 The latter study included 66 patients in whom either autograft (without BMP) or allograft struts augmented with BMP were used to obtain fusion. The autograft (without BMP) nonunion rate was twice as high as that of the allograft with BMP group. Considering safety, the use of BMP may be associated with postoperative swelling and dysphagia. With special techniques—correct packing of the BMP sponges, fibrin glue barriers to limit diffusion of BMP—the risk of postoperative swelling and dysphagia can be decreased to a rate that is comparable to that of ventral cervical fusions in which BMP is not used.51,53,54 Cahill et al.,55 on the other hand, found that there remains a higher complication rate with BMP going from wound-related complications to dysphagia and hoarseness. Facing cost, one should consider that a small package of BMP costs about $2500 U.S. Cahill et al. found that the inpatient hospital charges across all categories of fusion were greater if BMP was used. In conclusion, BMP utilization may increase fusion rates and avoid iliac crest harvest complications but seems to increase the overall complication rate. Cost-effectiveness is doubtful. Until there is better evidence on these issues, a cautious approach is certainly in order.

Complication Avoidance

Of utmost importance in avoiding complications with any operation for soft cervical disc herniations is to perform the appropriate operation on the appropriate patient. Correlating the clinical picture with the imaging abnormalities is crucial.56 It is known that ACDF is one of the most commonly performed spinal procedures. Its outcome is satisfactory in the majority of cases. However, occasional complications can become troublesome and even, in rare circumstances, catastrophic. Although there are several case reports describing such complications, their rate of occurrence is generally underreported, and data regarding their exact incidence in large clinical series are lacking. Meticulous knowledge of potential ACDF-related complications is of paramount importance in order to avoid them whenever possible, as well as to successfully and safely manage them when they happen.53

Complications Related to Cervical Disc Arthroplasty

Besides the intraoperative risks and possible complications that are, for the most part, the same as those seen with ventral discectomy and fusion techniques,57 one can specifically distinguish disc arthroplasty techniques as specifically being associated with immediate (e.g., malpositioning of the prosthesis), early (e.g., migration), intermediate (e.g., subsidence), and late (e.g., wear debris formation with osteolysis) postoperative complications. The impact of a cervical disc prosthesis and its long-term complications must be elucidated. Such complications can be minimized while providing optimal function by limiting this type of surgery to patients with appropriate indications.

Complications Related to Cervical Discectomy with Bone Fusion

Preoperative Period

In patients with a significant neurologic deficit, the preoperative use of corticosteroids may be considered. However, there are no convincing reports in the literature to support the efficacy of the routine use of corticosteroids in patients undergoing elective decompressive operation.56 As has been shown for trauma patients,58 corticosteroids are more likely to induce additional problems, especially in elderly patients, than they are to effectively diminish the risk of spinal cord or nerve injury.

Intraoperative Period56

Injury to the Structures in the Carotid Sheath

The carotid artery, the internal jugular vein, and the vagus nerve are at risk of damage in the lateral part of the operative field. Laceration of these structures is caused by the sharp teeth of retractor blades or during dissection with sharp instruments. For this reason, blunt dissection could be advisable. In most cases, carotid artery lacerations can be repaired primarily. Bleeding from the jugular vein should be controlled by repairing the laceration. In an ultimate case, ligation of the jugular vein should be considered. Injury to the vagus nerve is a very unusual complication, but if transsection is observed intraoperatively, primary anastomosis should be attempted.

Injury to the Vertebral Artery

Far lateral bone removal can damage the vertebral artery and is most likely to occur on the opposite side of the approach. An aggressive dissection of the longus colli muscles can also injure the artery between the transverse processes. Third, an anatomic variation with a midline loop of the vertebral artery into the vertebral body or intervertebral disc can cause problems. Commonly, bleeding can be controlled with gentle compression using a muscle pledget, hemostatic gelatin (Gelfoam), or oxidized cellulose (Surgicel). The risk of neurologic deficit after a unilateral vertebral artery occlusion is low, but this can be encountered if there is a congenital anomaly with absence of anastomosis between the left and the right vertebral arteries.61 Cases of the Wallenberg syndrome were described in such situations. To avoid this injury, one should identify the midline carefully and proceed with drilling accordingly.

Horner Syndrome

The cervical sympathetic chain is located ventral to the transverse process and ventrolateral to the longus colli muscle. Injury leads to Horner syndrome, which can result from either transsection or retraction of the sympathetic chain. The incidence of permanent injury is less than 1%. To avoid this injury during a ventral approach, the soft tissue dissection should be limited to the medial aspect of the longus colli muscle.62

Increased Neurologic Deficit

In an attempt to decrease the potential additional neurologic deficit, one can consider monitoring neurologic function with intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials. By doing this, spinal cord injury as well as nerve root injury may diminish.63 Since spinal cord compression is not very common in pure soft cervical disc herniations, the advantage of such a neurophysiologic backup is rather theoretical in this particular indication.

Postoperative Period56

Postoperative Infection

Although one can speculate that with cages and/or plates (and TDR) the infection rates may be higher, data in the literature are scarce. Exceptional case reports are described.64,65

Graft or Cage Complications

Bone graft complications include graft collapse, displacement (and subsidence), and nonunion (pseudarthrosis). Elderly patients with osteoporotic bone are most prone to display graft collapse. In case of doubt about the structural integrity of autologous bone, an allograft should be used. However, in younger patients, autologous graft is stronger than allograft in resisting axial compression. Most patients with graft collapse are asymptomatic and do not require reoperation.

Graft Displacement and Subsidence

Stand-alone cage subsidence appears to occur frequently but, as was stated earlier, does not seem to have significant clinical repercussions.66 Plating is reported to avoid subsidence, but such has not been shown via clinical studies.67

Biomechanics: Focus on Kyphosis

Kyphosis after ACD is classic and tends to become greater if the operation is performed on two levels rather than on one level. This could be explained by the fact that after discectomy, the disc space systematically collapses. Collapse occurs ventrally more than dorsally, owing to the dorsal structures of the vertebra (facet joints), which do not collapse, and because of the wedge shape of the cervical disc. This results in a reversal of lordosis or straightening of the cervical curve.26 Additional fusion (ACDF) is performed to overcome this problem.

Long-Term Benefit

Data from prospective observational studies indicate that 2 years after surgery for cervical radiculopathy caused by soft cervical disc herniation (without myelopathy), 75% of patients have substantial pain relief from radicular symptoms (pain, numbness, and weakness).68,69 Overall improvement of myelopathy symptoms may take longer than recovery from radicular symptoms.56

Bhadra A.K., Raman A.S., et al. Single-level cervical radiculopathy: clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness of four techniques of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion and disc arthroplasty. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:232-237.

Carette S., Fehlings M.G. Cervical radiculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:392-399.

Chou Y.C., Chen D.C., Hsieh W.A., et al. Efficacy of anterior cervical fusion: comparison of titanium cages, polyetheretherketone (PEEK) cages and autogenous bone grafts. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;15:1240-1245.

Fountas K.N., Kapsalaki E.Z., Nikolakakos L.G., et al. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion associated complications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(21):2310-2317.

Samartzis D., Shen F.H., Goldberg E.J., An H.S. Is autograft the gold standard in achieving radiographic fusion in one-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with rigid anterior plate fixation? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:1756-1761.

Sasso R.C., Smucker J.D., Hacker R.J., Heller J.G. Artificial disc versus fusion. A prospective, randomized study with 2-year follow up on 99 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:2933-2940.

Yue W.M., Bronder W., Highland T.R. Long term results after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with allograft and plating: 5-11 year radiologic and clinical follow up study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2138-2144.

1. Connolly E.S., Seymour R.J., Adams J.E. Clinical evaluation of anterior cervical fusion for degenerative cervical disc disease. J Neurosurg. 1965;23:431-437.

2. Stookey B. Compression of the spinal cord due to ventral extradural cervical chondromas. Diagnosis and surgical treatment. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1928;20:275-291.

3. Keyes D.C., Compere E.L. The normal and pathological physiology of the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disc. An anatomical, clinical and experimental study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1932;14:897-938.

4. Mixter W.J., Barr J.S. Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N Engl J Med. 1934;211:210-215.

5. Schmorl G. Uber Verlagerung von Bandscheiloengewebe und ihre Folgen. Arch Klin Chir. 1932;172:240-276.

6. Carette S., Fehlings M.G. Cervical radiculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:392-399.

7. Radhakrishan K., Litchy W.J., O’Fallon W.M., Kurland L.T. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy: a population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 1976 through 1990. Brain. 1994;117:325-335.

8. Kuijper B., Tans J.T., Schimsheimer R.J., et al. Degenerative cervical radiculopathy: diagnosis and conservative treatment. A review. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:15-20.

9. Fouyas I.P., Statham P.F., Sandercock P.A. Cochrane review on the role of surgery in cervical spondylotic radiculomyelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:736-747.

10. Peul W.C. Timing of surgery for sciatica. Leiden, The Netherlands: Doctoral thesis, Leiden University; 2008.

11. Ebersold M.J., Raynor R.B. Cervical laminectomy, laminectomy, laminoplasty and foraminotomy. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Spine surgery: techniques, complication avoidance, and management, vol 2. ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005:387-394.

12. Bailey R.W., Badgley C.E. Stabilization of cervical spine by anterior fusion. Am J Orthop. 1960;42:565-594.

13. Robinson R.A., Smith G.W. Anterolateral cervical disc removal and interbody fusion for cervical disc syndrome (Abstract). Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1955;96:223-224.

14. Cloward R.B. The anterior approach for removal of ruptured discs. J Neurosurg. 1958;15:602-614.

15. Dereymaeker A., Mulier J. Vertebral fusion by a ventral approach in cervical intervertebral disc disorders. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1958;99(6):597-616.

16. Bohler J., Gaudernak T. Anterior plate stabilization for fracture: dislocations of the lower cervical spine. J Trauma. 1980;20:203-205.

17. Brigham C.D., Tsahakis P.J. Anterior cervical foraminotomy and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:766-770.

18. Brodke D.S., Zdeblick T.A. Modified Smith-Robinson procedure for anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992;17:427-430.

19. Chang K.W., Lin G.Z., Liu Y.W., et al. Intraosseous screw fixation of anterior cervical graft construct after discectomy. J Spinal Disord. 1994;7:126-129.

20. Emery S.E., Bolesta M.J., Banks M.A., Jones P.K. Robinson anterior cervical fusion: comparison of the standards and modified techniques. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:660-663.

21. Galera R., Tovi D. Anterior disc excision with interbody fusion in cervical spondylitic myelopathy and rhizopathy. J Neurosurg. 1968;28:305-310.

22. Hakuba A. Trans-unco-discal approach: a combined anterior and lateral approach to cervical discs. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:284-291.

23. Kambin P. Anterior approach to the cervical disc with bone grafting. Mt Sinai J Med. 1994;61:243-245.

24. McGuire R.A., St. John K. Comparison of anterior cervical fusions using autogenous bone graft obtained from the cervical vertebrae to the modified Smith-Robinson technique. J Spinal Disord. 1994;7:499-503.

25. Snyder G.M., Bernhardt M. Anterior cervical fractional interspace decompression for treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a review of the first 66 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;246:92-99.

26. Zeidman S.M., Ducker T.B. Posterior cervical laminoforaminotomy for radiculopathy: review of 172 cases. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:356-362.

27. Abd-Alrahman N., Dokmak A.S., Abou-Madawi A. Anterior cervical discectomy (ACD) versus anterior cervical fusion (ACF), clinical and radiological outcome study. Acta Neurochir. 1999;14:1089-1092.

28. Hirsch C. Cervical disc rupture. Diagnosis and therapy. Acta Orthop Scand. 1960;30:172-186.

29. Yue W.M., Bronder W., Highland T.R. Long term results after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with allograft and plating: 5-11 year radiologic and clinical follow up study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2138-2144.

30. Sasso R.C., Smucker J.D., Hacker R.J., Heller J.G. Artificial disc versus fusion: a prospective, randomized study with 2-year follow up on 99 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:2933-2940.

31. Walraevens J., Liu B., Vander Sloten J., Goffin J. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of degeneration of cervical intervertebral discs and facet joints. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:358-369.

32. Wigfield C.C., Gill S.S., Nelson R.J., et al. The new Frenchay artificial cervical joint: results from a two year pilot study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:2446-2452.

33. Goffin J., Casey A., Kehr P., et al. Preliminary clinical experience with the Bryan cervical disc prosthesis. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:840-847.

34. Peng-Fei S., Yu-Hua J. Cervical disc prosthesis replacement and interbody fusion: a comparative study. Int Orthop. 2008;32:103-106.

35. Walraevens J., Demaerel P., Suetens P., et al. Longitudinal prospective long-term radiographic follow up after treatment of single-level cervical disc disease with the Bryan cervical disc. Neurosurgery. 2010;67(3):679-687. discussion 687

36. Yi S., Lim J.H., Choi K.S., et al. Comparison of anterior cervical foraminotomy vs arthroplasty for unilateral cervical radiculopathy. Surg Neurol. 2009;71:677-680.

37. Bhadra A.K., Raman A.S., Casey A.T.H., et al. Single-level cervical radiculopathy: clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness of four techniques of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion and disc arthroplasty. Aur Spine J. 2009;18:232-237.

38. Zileli M., Benzel E.C., Bell G.R. Bone graft harvesting. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Spine surgery: techniques, complication avoidance, and management, vol 2. ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005:1253-1261.

39. Samartzis D., Shen F.H., Goldberg E.J., An H.S. Is autograft the gold standard in achieving radiographic fusion in one-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with rigid anterior plate fixation? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:1756-1761.

40. Samartzis D., Shen F.H., Lyon G., et al. Does rigid instrumentation increase the fusion rate in one-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion? Spine J. 2004;4:636-643.

41. Martin G.J., Haid R.W., MacMillan M., et al. Anterior cervical discectomy with freeze-dried fibula allograft. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:852-859.

42. Bagby G.W. Arthrodesis by the distraction-compression method using a stainless steel implant. Orthopedics. 1988;11:931-934.

43. Chou Y.C., Chen D.C., Hsieh W.A., et al. Efficacy of anterior cervical fusion: comparison of titanium cages, polyetheretherketone (PEEK) cages and autogenous bone grafts. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;15:1240-1245.

44. Löfgren H., Engquist M., Hoffmann P., et al. Clinical and radiological evaluation of Trabecular Metal and the Smith-Robinson technique in anterior cervical fusion for degenerative disease: a prospective, randomized, controlled study with 2 year follow up. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(3):464-473.

45. Cho D.Y., Lee W.Y., Sheu P.C. Treatment of multilevel cervical fusion with cages. Surg Neurol. 2006;62:378-385.

46. Kaiser M.G., Haid R.W.Jr., Subach B.R., et al. Anterior cervical plating enhances arthrodesis after discectomy and fusion with cortical allograft. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:229-238.

47. Shapiro S., Connolly P., Donaldson J., et al. Cadaveric fibula, locking plate and allogeneic bone matrix for anterior cervical myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:43-50.

48. Savolainen S., Rinne J., Hernesniemi J. A prospective randomized study of anterior single level cervical disc operations with long term follow up: surgical fusion is unnecessary. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:51-55.

49. Silber J.S., Anderson D.G., Daffner S.D., et al. Donor site morbidity after iliac crest bone harvest for single level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(2):134-139.

50. Hilibrand A.S., Yoo J.U., Carlson G.D., et al. The success of anterior cervical arthrodesis adjacent to a previous fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(14):1574-1579.

51. Tumialan L.M., Pan J., Rodts G.E., et al. The safety and efficacy of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with polyetheretherketone spacer and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: a review of 200 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8(6):529-535.

52. Bettermann G.R. Prospective nonrandomized comparison of an allograft with bone morphogenetic protein versus an iliac crest autograft in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine J. 2008;8(3):426-435.

53. Fountas K.N., Kapsalaki E.Z., Nikolakakos L.G., et al. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion associated complications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(21):2310-2317.

54. Patel V.V., Zhao L., Wong P., et al. Controlling bone morphogenetic protein diffusion and bone morphogenetic protein-stimulated bone growth using fibrin glue. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(11):1201-1206.

55. Cahill K.S., Chi J.H., Day A., et al. Prevalence, complications and hospital charges associated with use of bone morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA. 2009;302(1):58-66.

56. Hanbali F., Gokaslan Z.L., Cooper P.R. Ventral and ventrolateral subaxial decompression. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Spine surgery: techniques, complication avoidance, and management, vol 2. ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005:341-350.

57. Riley L., Skolasky M., Albert T., et al. Dysphagia after anterior cervical decompression and fusion: prevalence and risk factors from a longitudinal cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;20:564-569.

58. Casha S., Silvaggio J., Hurlbert J. Pharmacotherapy for spinal cord injury. In: Amar A.P., editor. Surgical management of spinal cord injury: controversies and consensus. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Futura; 2007:18-33.

59. Ardon H., Van Calenbergh F., Van Raemdonck D., et al. Oesophageal perforation after anterior cervical surgery: management in four patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2009;151(4):297-302.

60. Sharma R.R., Sethu A.U., Lad S.D., et al. Pharyngeal perforation and spontaneous extrusion of the cervical graft with its fixation device: a late complication of C2-C3 fusion via anterior approach. J Clin Neurosci. 2001;8:464-468.

61. Goffin J., Van Brussel K., Vander Sloten J., et al. 3D-CT based, personalized drill guide for posterior transarticular screw fixation at C1-2: technical note. Neuro-Orthopedics. 1999;25:47-56.

62. Yasumoto Y., Abe Y., Tsutsumi S., et al. Rare complication of anterior spinal surgery: Horner syndrome. No Shinkei Geka. 2008;36:911-914.

63. Epstein N. Intraoperative evoked potential monitoring. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Spine surgery: techniques, complication avoidance, and management. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:1249-1257.

64. Martinez-Lage J.F., Felipe-Murcia M., Martinez-Lage Azorin L. Late prevertebral abscess following anterior cervical plating: the missing screw. Neurocirurgia. 2007;18:111-114.

65. Talmi Y.P., Knoller N., Dolev M., et al. Postsurgical prevertebral abscess of the cervical spine. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1137-1141.

66. Gercek E., Arlet V., Delisle J., Marchesi D. Subsidence of stand alone cervical cages in anterior interbody fusion: warning. Eur Spine J. 2004;12:513-516.

67. Samartzis D., Marco R.A., Jenis L.G., et al. Characterization of graft subsidence in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with rigid plate fixation. Am J Orthop. 2007;36:421-427.

68. Hacker R.J., Cauthen J.C., Gilbert T.J., Griffith S.L. A prospective randomized multicenter clinical evaluation of an anterior cervical fusion cage. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:2646-2654.

69. Casha S., Fehlings M.G. Clinical and radiological evaluation of the Codman semiconstrained load-sharing anterior cervical plate: prospective multicenter trial and independent blinded evaluation of outcome. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:264-270.