CHAPTER 158 Management of Pain by Anesthetic Techniques

Considerations for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Injections

Diagnostic Injection

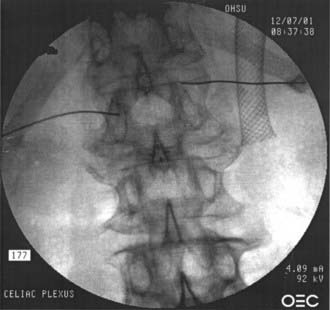

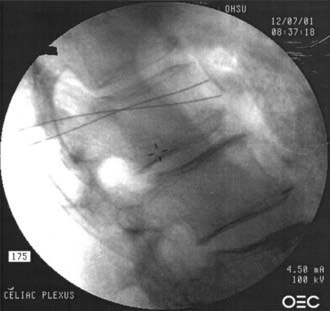

Application of local anesthetics to nervous tissue decreases transmission of sensory and motor information by means of sodium channel blockade. Knowledge of neural innervation patterns and anatomy allows targeted injection of local anesthetics (Figs. 158-1 and 158-2). If effective, the temporary pain relief that lasts until the local anesthetic blockade is reversed provides the basis for diagnostic injections. The blockade assists in confirmation of location of underlying pathology, or confirmation of mechanism, as seen in sympathetically mediated pain.

FIGURE 158-1 Anteroposterior view of a celiac plexus block.

(Courtesy of Brett Stacey, Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine, Portland, OR.)

FIGURE 158-2 Lateral view of a celiac plexus block.

(Courtesy of Brett Stacey, Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine, Portland, OR.)

When an injection or any interventional procedure is the basis for diagnosis or future treatment, careful attention to patient selection, technique, and process is critical.1 The patient must understand in advance that the injection is intended as a diagnostic or prognostic maneuver, not as therapy. A general approach to diagnostic injections is summarized in Table 158-1.

Therapeutic Injection

The rationale for including corticosteroids in therapeutic injections is based on the principle that perineural inflammation accompanies painful conditions. The numerous anti-inflammatory and membrane-stabilizing properties of steroids may contribute to decreased sensitization, decreased edema, and pain relief when steroid is injected into the vicinity of painful nerves. Animal models demonstrate that steroids can beneficially modify the effects of neurogenic inflammation by decreasing thermal hyperalgesia,2 decreasing phospholipase A2 activity,3 inhibiting prostaglandin production,4 and blocking normal C-fiber firing.5

Limitations of Neural Blockade and Therapeutic Injection

Limitations Associated with Neural Blockade

Pain is a subjective experience; patient cooperation and feedback are the basis for interpretation of diagnostic neural blockade. There may be an incidence of placebo response or expectation bias as high as 35% with each injection.6,7 Physicians must be attentive to their own bias when discussing pending diagnostic procedures because the patient response may be influenced by physicians’ suggestions, expectations, and interactions.8,9

The patient may have more than one type of pain or source of pain that may confound the patient’s interpretation of the injection, leading to a partial response open to interpretation. Anatomic and physiologic variations may lead to incomplete block, block of unintended nerves, or lack of effectiveness.10,11 Postoperative changes may limit flow of injectate, obscure landmarks, or alter anatomy.

Limitations of Therapeutic Injections

It is a rare occurrence when we can attribute chronic pain conditions to a single cause. There may be musculoskeletal factors, a psychosocial dynamic, or a functional loss that can influence the impact of the pain syndrome on the patient. In addition, universal neural blockade technique standards do not exist. For example, a patient referred for nerve blocks for the diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome (i.e., reflex sympathetic dystrophy) of an upper extremity could receive an impressive variety of nerve-blocking techniques for this condition. Injection at the stellate ganglion with or without fluoroscopic guidance, a posterior paravertebral approach to the upper thoracic sympathetic chain, injection into the epidural space, performance of an intravenous regional anesthetic, and performance of a brachial plexus block are some of the options available for this condition. For each of these, local anesthetic, steroid, opioid, clonidine, guanethidine, reserpine, bretylium, or a variety of other medications could be employed.12,13

Imaging Guidance

Fluoroscopy

Most fluoroscopy units produce images with an image intensifier and have a “last image hold” function, which allows recalling the last image without having to again expose the patient to radiation. Many newer fluoroscopy units offer a “pulsed fluoro mode,” which is often used to follow the spread of contrast material in real time. In pulsed mode, the x-ray beam is pulsed rapidly on and off, resulting in a lower radiation dose compared with continuous fluoroscopy.14 Quick and easy correlation of surface anatomy with the radiographic image is allowed by use of a laser guidance system. This also decreases fluoroscopy time and radiation dose.

During fluoroscopy, contrast material provides opacification of blood vessels and tissues. Nonionic contrast agents such as iohexol, iotrolan, iomeprol, and iodixanol are water soluble and have a lower potential for central nervous system toxicity, renal impairment, or anaphylactoid reactions compared with ionic agents.15–18 Using fluoroscopy in the anteroposterior, lateral, or oblique views, the pattern of spread visualized after injecting contrast agent can be used to delineate different tissue planes and proper needle placement before the introduction of local anesthetic, steroids, or neurolytic substances.

Epidural steroid injections (ESIs) originally were performed using a “blind” technique without fluoroscopic guidance. Injecting variable amounts of radiologic contrast material under fluoroscopic observation before therapeutic injection improves safety and efficacy. White19 found that inaccurate needle placement occurred in 25% to 30% of blind injections, even in the hands of skilled and experienced proceduralists.

Ultrasound

The modality of ultrasound imaging has been successfully adopted to perform peripheral nerve blocks and catheter placement in the field of regional anesthesiology. There is also some evidence that ultrasound guidance is useful when performing percutaneous pain procedures. Ultrasonography is free from radiation, is easy to use, and can provide real-time images to guide needle placement. Chen and coworkers20 found that when ultrasound was used to guide the epidural needle through the sacral hiatus while performing a caudal ESI, it was accurate 100% of the time when confirmed with contrast-dye fluoroscopy.

Chronic neck pain after whiplash injury is caused by trauma to the cervical zygapophyseal (facet) joints in about 50% of patients. Using ultrasound guidance in 14 volunteers, Eichenberger and coworkers21 were able to visualize and inject adjacent to the third occipital nerve when attempting to block the nervous supply of the C2-3 facet joint. Fluoroscopy, however, demonstrates only the bony adjacent structures, not soft tissue structures such as nerves. Finally, Gruber and associates22 performed neurosclerosis in 82 patients with residual limb neuroma using ultrasound guidance and reported that these patients appeared to have better outcomes than those who received injections without ultrasound guidance.

Epidural and Selective Nerve Root Injections

ESIs have been described as the “bread and butter” of injection treatment for neck, back, and radiculopathic extremity pain. Published studies and commentaries have emphasized the safety of ESIs but questioned the efficacy of the technique and highlighted the ubiquitous, nondiscriminant application of ESIs.23 Between 1996 and mid-2006, 69 ESI–related papers were published in the English-speaking medical literature. Prospective outcome studies are a small minority of these publications, whereas more than 50% are letters and reports of adverse events involving ESIs.24

No conclusive prospective, randomized outcome studies have demonstrated long-term benefit, and multiple studies have demonstrated an outcome similar to placebo after 2 weeks.24 The Wessex Epidural Steroids Trial (WEST)25 study group found that neither single nor multiple ESIs improved on placebo when pain outcomes were measured 35 days after injection. Despite these controversies, ESIs probably have an important role to play in selected patients, particularly those with radicular pain.26 The success of this important therapeutic procedure depends on attention to patient selection, technique, and concomitant therapies.

Rationale for Epidural Steroid Injections

It is well known that a herniated disk pressing on a nerve root can produce radicular pain. Inflammation may play a role in symptomatic nerve root irritation that is associated with herniated intervertebral disks.27 Proinflammatory substances are contained in extruded nucleus pulposus material and may produce an inflammatory response in the epidural space and in the underlying nerve roots.28–31 It is likely that pain and other symptoms are produced by a combination of this inflammatory response, edema, and the mechanical pressure on nerve roots.

Indications, Contraindications, and Limitations

Radicular extremity pain that has not responded to more conservative treatment is the primary indication for ESI (Table 158-2). ESI is not indicated for the treatment of mechanical or muscular axial back pain. Outcome studies do not clearly support the use of ESIs in spinal stenosis patients,32 but many clinicians feel that they can be helpful in this population, particularly in patients with radicular symptoms. Benefit in patients with prior back surgery is less clear, but many believe a subset of these patients benefits from ESI as well.26

| INDICATIONS | CONTRAINDICATIONS | FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH FAILURE |

|---|---|---|

| Herniated nucleus pulposus with extremity pain in a radicular pattern | Anticoagulation Infection at the site |

Smoking Unemployed |

| Foraminal stenosis with radicular symptoms | Other pain that is more intense | Long duration |

| Spinal stenosis with extremity symptoms Imaging studies with concordant findings |

Nonradicular pain

Adapted from Hopwood MB, Abram SE. Factors associated with failure of lumbar epidural steroids. Reg Anesth. 1993;18:238-243; and Jamison RN, VandeBoncouer T, Ferrante FM. Low back pain patients unresponsive to an epidural steroid injection: Identifying predictive factors. Clin J Pain. 1991;7:311-317.

Hwang and colleagues33 reported in a prospective, nonrandomized study that ESI is helpful in treating the pain of acute herpes zoster virus (HZV) infection. Manabe and associates34 demonstrated that in addition to systemic antiviral treatment, an epidural infusion with local anesthetic was superior to saline in a prospective randomized trial at reducing pain and allodynia. ESIs administered during the acute stage can be used for the prevention of postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) and shorten the duration of pain.

Interlaminar versus Transforaminal

In a small study, Thomas and colleagues35 compared loss-of-resistance interlaminar ESI with fluoroscopically guided transforaminal ESI and found improved pain relief, functional, and quality-of-life indicators 6 months after injection in the transforaminal group. In addition, Ackerman and Ahmad36 studied 90 patients with L5-S1 disk herniation and found that the transforaminal route of administration was superior to the caudal and interlaminar routes.

Injection Technique

The goal of the injection is to deliver steroid as a single agent or combined with local anesthetic to the presumed source of pain and symptoms. Delivery techniques vary widely, and a variety of solutions and volumes are commonly used.37 Two very common techniques in widespread use are the parasagittal or midline interlaminar and the transforaminal approaches.

Interlaminar and Caudal Injection Techniques

Without the use of fluoroscopic guidance, failure to achieve injection into the epidural space has been reported to be as high as 12% to 38%.37,38 A prospective study of patients with previous back operations demonstrated a failure rate of 53% in placing an epidural needle at the desired level based on surface anatomy alone and only a 26% success rate in delivering injectate to the level of pathology.37 In a retrospective study, Johnson and colleagues39 demonstrated that combining epidurography with ESI permitted safe and accurate therapeutic injections with an exceedingly low incidence of complications.

Transforaminal Injection Technique

With the patient in a prone position, the primary lumbar landmarks for performing this injection are the transverse process above the desired nerve root representing the superior aspect of the neuroforamen. The target area is referred to as the safe triangle because it does not contain neural structures and therefore limits the opportunity for direct nerve damage from the needle40 (see “Fluoroscopy” earlier).

Outcomes and Adverse Events

Dunbar and coworkers41 performed a sophisticated study in which they measured inline epidural infusion pressure in patients with degenerative spinal disease in a group of patients who had undergone an ESI. Initially, these patients had significantly increased infusion pressures compared with unaffected patients, which reflects outflow resistance or obstruction. There was a significant decrease in inline epidural infusion pressure when it was measured 3 weeks after an ESI. This led the investigators to suggest that ESIs are helpful in decreasing epidural space encroachment by likely inflamed and edematous neural structures.

Carette and associates42 published a randomized, double-blind trial of 158 subjects who received up to three injections of methylprednisolone acetate and saline, compared with a smaller volume of saline alone for patients with sciatica due to herniated nucleus pulposus. The steroid group had short-term improvements in leg pain, mobility, and sensory deficits and no long-term benefit or change in eventual surgical intervention rate. This study has been widely referenced by non–pain specialists as evidence that epidural steroids have little role in managing radicular pain, whereas pain physicians have noticed the ESI technique deficiencies.

Along the line that ESIs provide short-term relief most predominantly, there are other such studies. Buchner and coworkers43 studied the effect of an ESI injection containing 100 mg methylprednisolone in 10 mL of bupivacaine compared with no treatment in 36 patients. They found that after 2 weeks, patients receiving the ESI showed a significant improvement in straight leg raise testing and that the treatment may be valuable in the acute phase. However, after 6 weeks and 6 months, pain relief and improvement of straight leg raising and functional status showed no statistical significance.

Hooten and colleagues44 reported on an epidural abscess and meningitis after ESI, which occurred in an elderly patient with neutropenia who suffered an inadvertent dural puncture. They thought that antibiotic prophylaxis for Staphylococcus aureus should be considered for immunocompromised patients undergoing such injections.

Facet Joint and Medial Branch Nerve Procedures

Intra-articular Facet Joint Injections

Injections into the lumbar facet joint are a popular, if somewhat understudied, modality of treating lumbar spinal pain. Advances in technology, specifically in the area of radiographic visualization, have made fluoroscopic identification of the facet joint and subsequent cannulation possible. However, because of extravasation of injectate into the epidural space or surrounding musculature, the lack of specificity of this technique led to its discredit as a diagnostic tool.45,46 Further investigation into the utility of these injections as a therapy for acute back pain also diminished enthusiasm because intra-articular injections of local anesthetic and corticosteroid were found to be similar to placebo injections several months after injections.47

Despite some of these outcome studies, facet joint injection is frequently performed because of the ease of injection into the facet joint. To improve the ease and accuracy of the injections, ultrasound has been studied as an imaging modality in placing the injections.48 The efficacy of facet joint injections alone for axial back pain and improved function has been questioned. Some suggest that facet joint injections along with physical therapy may be helpful in improving pain and range of motion.49

Lumbar Medial Branch Denervation

Bogduk and Long50 clarified the neuroanatomy of the facet joint in the late 1970s. This improved understanding, along with improvements in technology, allowed for development of radiofrequency neurodestructive procedures, including radiofrequency energy to disrupt the nervous supply (medial branch nerves) of the facet joints. Some studies have indicated that this treatment improves pain, but perhaps not over placebo.51,52 A recent analysis found that psychological variables played a large role in long-term outcomes from denervations.53

Cervical and Thoracic Medial Branch Denervation

The same principles and techniques used in diagnosing and treating lumbar pain from facet arthropathy have been applied to the cervical spine. One recent study also called the efficacy of cervical medial branch denervation into question.54 However, radiofrequency cervical medial branch denervation demonstrated prolonged benefits in other studies.55,56 McDonald and associates57 reported significant pain relief after radiofrequency cervical medial branch denervation in 71% of treated patients. The patients with success had a median duration of relief of 422 days. Also, repeating the denervation procedure potentially could treat recurrent pain.

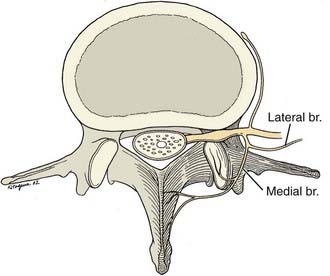

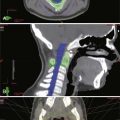

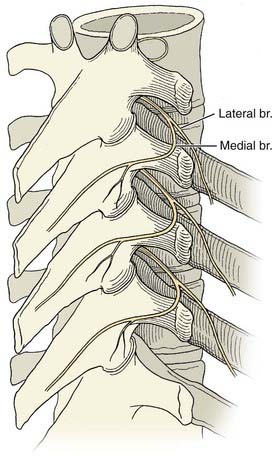

Neuroanatomy

Facet joints begin at C1-2 and are present down to the L5-S1 levels. They are synovial joints, with the capsule and synovium extensively innervated with sensory fibers. Innervation includes mechanoreceptors58 and involves multiple neurotransmitters such as substance P,59 which are linked to nociception.60,61 Their innervation is thought to be segmental and based primarily on the medial branch of the primary posterior ramus of each segmental spinal nerve (Fig. 158-3).37

FIGURE 158-3 Thoracic space anatomy.

(Courtesy of Brett Stacey, Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine, Portland, OR.)

The medial branch innervates the multifidus muscle segmentally in addition to the facet joint capsule and its contents. This muscle, itself a significant pain generator, may account for some of the analgesia associated with lumbar medial branch blocks and denervations.62,63 Except for this muscle, there is no other significant structure for which the medial branch is the sole innervation. The anatomy of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar medial branches is demonstrated in Figure 158-4.

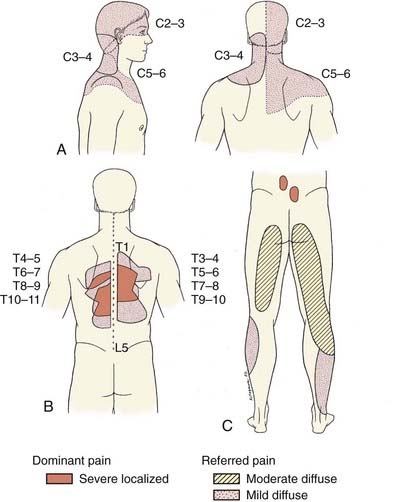

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of pain due to facet arthropathy is based on an accurate history and physical examination. Several physical examination characteristics are used to select patients for diagnostic lumbar medial branch blocks; classic signs include localized low back pain exacerbated by rotation and extension64 with referral in a stereotypical distribution (Fig. 158-5). Incorporating facet-loading maneuvers into the physical examination of the lumbar spine is recommended. Physical evaluation of the lumbar spine for facet arthropathy includes characteristics such as localized unilateral low back pain, pain on unilateral palpation of the facet joint or transverse process, lack of radicular features, pain eased by flexion, and pain, if referred, located above the knee.65 A sequence of diagnostic injections of the medial branches is performed to help secure the diagnosis.

FIGURE 158-5 Referral patterns for cervical (A), thoracic (B), and lumbar facets (C).

(A, Adapted from Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, Bogduk N. Chronic cervical zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash. Spine. 1996;21:1737-1745. B, Adapted from Dreyfuss P, Tibiletti C, Dreyer SJ. Thoracic zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. Spine. 1994;19:807-811. C, Adapted from Fukui S, Ohseto K, Shiotani M, et al. Distribution of referred pain from the lumbar zygapophyseal joints and dorsal rami. Clin J Pain 1997;13:303-307.)

There was originally much speculation about the appropriate diagnostic regimen, but most clinicians use the so-called two-block paradigm. With this method, the patient is subjected to two sets of diagnostic, fluoroscopically guided medial branch injections.66 These injections are usually single blinded (i.e., the clinician knows the contents of the injection; the patient does not) and contain a long-acting (e.g., 0.5% bupivacaine) or short-acting (2% lidocaine) local anesthetic. The patient is not sedated during the procedure. After the procedure, the patient is asked to complete a pain diary, recording numeric rating scale values representing the pain.

Pain relief in each of the two blocks that is concordant with the expected duration of the local anesthetic is required before the clinician makes a decision to perform radiofrequency denervation. One important consideration when using this model to guide further treatment is that it has fairly high false-positive rates, ranging from 15% to 67%, with one large retrospective study finding about 40% for cervical, thoracic, and lumbar blocks.67 No other single model has emerged as a validated model to replace it.

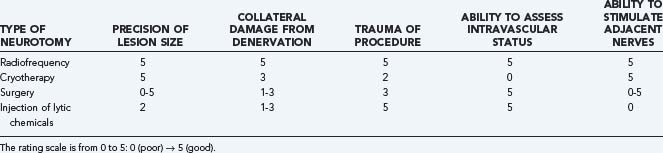

Radiofrequency Denervation Treatment

Procedure

Neurolysis can be achieved using many techniques.68 Various technical considerations have led to the use of radiofrequency energy as the method of choice for denervation of the medial branch (Table 158-3). Equipment improvements include small-diameter (22-gauge) and curved probes, which minimize tissue trauma and improve navigation. The lesion generator, which is also used for intracranial functional neurosurgery, allows multiple settings, depending on the procedure. Of greater importance is the ability to stimulate the adjacent structures with a harmless neurostimulating electrical field (motor and sensory testing) before denervation to rule out contact with the nerve roots. Although not universally used, this is a potentially significant safety advantage of this technique.

The medial branches of two segmental spinal nerves innervate each facet joint ipsilaterally (see Fig. 158-4). To effect anesthesia of the lumbar medial branch, the radiofrequency cannula has to be positioned precisely slightly inferior to the junction of the transverse process and the pedicle at each lumbar level. At the sacrum, the dorsal ramus of L5 is denervated in the sacral alar notch.69 Also commonly denervated is the S1 contribution to the L5-S1 joint, the dorsal ramus that exits the superior aspect of the ipsilateral S1 neural foramen.70

At the cervical levels inferior to C3, the active tip must be positioned in the concave aspect of the lateral articular pillar of the transverse process at each segment. At C3, the anatomy is similar to the inferior segments, except that it has a superficial branch that runs immediately posterior to the C2-3 facet joint and becomes the third occipital nerve, which is partially responsible for the sensory innervation of the posterior skull and scalp. In denervating this nerve as it passes posterior to the C2 lateral articular pillar, the C2 component of the C2-3 joint and the third occipital nerve are lesioned.65

The thoracic anatomy can be more involved, but facet-related pain is less common in this distribution. Successful medial branch denervations have, however, been performed in the thoracic spine after the discovery that, at several levels, the medial branch exists in a plane not adjacent to the transverse process. The course of the medial branches of the thoracic dorsal rami is lumbar in character at T11 and T12 only. The other thoracic levels assume a different anatomic distribution. A two-needle technique has been advocated for this region.71 With the two-needle technique, one needle is inserted to contact the lateral third of the transverse process, and a second is positioned at the identical depth (as verified by lateral fluoroscopy) but cephalad, to be near the medial branch without puncturing the lung.

Outcomes

The prolonged effects of radiofrequency medial branch denervation have been demonstrated in numerous studies. The cervical region is the most thoroughly studied of these procedures. In this area, 75% of the treatment group had at least 50% analgesia for a median duration of 263 days.66 With radiofrequency denervation, the neuronal contents are selectively coagulated, and neuronal function is interrupted. However, the neuronal substrate remains.68,70 This allows regrowth of the nerve about 8 to 12 months after the procedure but prevents neuroma formation.

Sympathetic Nerve Blocks

Anatomy of the Sympathetic Nervous System

These preganglionic fibers, as the name implies, eventually synapse in one of the sympathetic ganglia. After synapsing, the postganglionic fibers then travel to their site of action.72 Afferent fibers carrying pain and visceral sensation travel along the somatic nerves (carrying somatic pain) or travel as hitchhikers with the sympathetic nerves (carrying visceral pain and sensation). Those afferent fibers pass through the sympathetic ganglia but do not synapse there. They are thin, unmyelinated nerves, commonly classified as C fibers, which transmit burning, aching pain. These fibers enter the spinal cord through the dorsal roots, and they have their cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglia. Because these visceral sensory nerves travel beside the sympathetic nerves, sympathetic nerve blocks inevitably anesthetize these nerves as well.

Stellate Ganglion Block

The efficacy of stellate ganglion blockade for the management of CRPS I was studied by Ackerman and Zhang73 using three blocks performed at weekly intervals. Laser Doppler fluxmetric hand perfusion studies were performed on normal and treated subjects. The investigators concluded that an inverse relationship existed between hand perfusion and the duration of symptoms of CRPS I. In addition, they concluded that there was a positive correlation between stellate ganglion block efficacy and how soon the therapy was initiated. They found that if symptoms existed for longer than 16 weeks before therapy or if the skin perfusion had decreased 22% or greater compared with the unaffected hand, the efficacy of the blocks was reduced.

Lumbar Sympathetic Block

There have not been many prospective studies regarding outcomes of lumbar sympathetic blocks as a treatment for lower extremity disorders. Of interest is a study by Tran and coworkers,74 who performed 28 lumbar sympathetic blocks in an attempt to correlate cutaneous toe temperature change with relief of allodynia. They found that a successful lumbar sympathetic block was realized when ipsilateral toe temperatures increased to within 3° C of core temperature. They suggest that cutaneous toe temperatures approaching core temperature may predict relief of sympathetically maintained pain.

Two approaches to the lumbar sympathetic chains are commonly in use: the paramedian approach and the lateral approach. In the paramedian approach, the needles enter the skin at about the level of the transverse process and 5 to 6 cm lateral to the midline. The lateral approach begins 9 to 10 cm lateral to the midline. These two different approaches have their own advantages and disadvantages, but they are essentially identical in their ease and risks.75

Arden NK, Price C, Reading I, et al. A multicentre randomized controlled trial of epidural corticosteroid injections for sciatica: the WEST Study. Rheumatology. 2005;44:1399-1406.

Bogduk N. Epidural steroids. Spine. 1995;20:845-848.

Brown PH. Medical Fluoroscopy: Guide for Safe Usage. Portland: Oregon Health Sciences University; 1997.

Dirkson R, Rutgers MJ, Coolen MW. Cervical epidural steroids in reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Anesthesiology. 1987;66:7173.

Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk DC. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic review. Pain. 1992;49:221-230.

Gruber H, Glodny B, Bodner G, et al. Practical experience with sonographically guided phenol instillation of stump neuroma: predictors of effects, success, and outcome. Am J Radiol. 2008;190:1263-1269.

Hogan QH, Abram SE. Neural blockade for diagnosis and prognosis. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:216-241.

; International Spinal Injection Society (ISIS). Standards for the performance of procedures involving spinal injection. Available at www.spinalinjection.com/ISIS/standard/standl.htm

Jamison RN, VandeBoncouer T, Ferrante FM. Low back pain patients unresponsive to an epidural steroid injection: identifying predictive factors. Clin J Pain. 1991;7:311317.

Manabe H, dan K, Hirata K, et al. Optimum pain relief with continuous epidural infusion of local anesthetics shortens the duration of zoster-associated pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:302-308.

McDonald GJ, Lord SM, Bogduk N. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with cervical radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:6168.

Moran R, O’Connell D, Walsh M. The diagnostic value of facet joint injections. Spine. 1988;13:1408-1410.

Rocco AG, Palombi D, Raeke D. Anatomy of the lumbar sympathetic chain. Reg Anesth. 1995;20:13-19.

Saal JS. General principles of diagnostic testing as related to painful lumbar spine disorders: a critical appraisal of current diagnostic techniques. Spine. 2002;27:2538-2545.

Sibell DM, Fleisch JM. Interventions for low back pain: what does the evidence tell us? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2007;11:14-19.

Stanton-Hicks M, Kaigle A, Reikeras O, Holm S. Complex regional pain syndromes: guidelines for therapy. Clin J Pain. 1998;14:155-166.

Thomas E, Cyteval C, Abiad L, et al. Efficacy of transforaminal versus interspinous corticosteroid injection in discal radiculalgia: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:299-304.

Turk DC, Stacey BR. Multidisciplinary pain centers in the treatment of chronic back pain. In: Frymoyer JW, Sucker TB, Hadler NM, et al, editors. Adult Spine: Principles and Practice. 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997:235-274.

Turner JA, Deyo RA, Loeser JD, et al. The importance of placebo effects in pain treatment and research. JAMA. 1994;271:1609-1614.

Weishaupt D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. MR imaging of the lumbar spine: prevalence of intervertebral disk extrusion and sequestration, nerve root compression, end plate abnormalities, and osteoarthritis of the facet joints in asymptomatic volunteers. Radiology. 1998;209:661-666.

1 Saal JS. General principles of diagnostic testing as related to painful lumbar spine disorders: a critical appraisal of current diagnostic techniques. Spine. 2002;27:2538-2545.

2 Hayashi N, Weinstein JN, Meller ST, et al. The effect of epidural injection of betamethasone or bupivacaine in a rat model of lumbar radiculopathy. Spine. 1998;23:877-885.

3 Lee HM, Weinstein JN, Meller ST, et al. The role of steroids and their effects on phospholipase A2. Spine. 1998;23:1191-1196.

4 Kantrowitz F, Robinson DR, McGuire MB, Levine L. Corticosteroids inhibit prostaglandin production by rheumatoid synovia. Nature. 1975;258:737-739.

5 Johansson A, Hao J, Sjolund B. Local corticosteroid application blocks transmission in normal nociceptive C-fibers. Acta Anesthesiol Scand. 1990;34:335-338.

6 Verdugo RJ, Ochoa JL. Reversal of hypoaesthesia by nerve block, or placebo: a psychologically mediated sign in chronic pseudoneuropathic pain patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:196-203.

7 Turner JA, Deyo RA, Loeser JD, et al. The importance of placebo effects in pain treatment and research. JAMA. 1994;271:1609-1614.

8 Fine PG, Roberts WJ, Gillette RG, Child TR. Slowly developing placebo responses confound tests of intravenous phentolamine to determine mechanisms underlying idiopathic chronic low back pain. Pain. 1994;56:235-242.

9 Gracely RH, Dubner R, Deeter WR, Wolskee PJ. Clinicians’ expectations influence placebo analgesia [letter]. Lancet. 1985;1:43.

10 Kirgis HD, Kuntz A. Inconsistent sympathetic denervation of the upper extremity. Arch Surg. 1942;44:95-102.

11 Cicala RS, Jones JW, Westbrook LL. Causalgic pain responding to epidural but not sympathetic nerve blockade. Anesth Analg. 1990;70:218-219.

12 Dirkson R, Rutgers MJ, Coolen MW. Cervical epidural steroids in reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Anesthesiology. 1987;66:7173.

13 Bloncherd J, Ramamurthy S, Walsh N, et al. Intravenous regional sympatholysis: a double-blind comparison of guanethidine, reserpine, and normal saline. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1990;5:357-361.

14 Brown PH. Medical Fluoroscopy: Guide for Safe Usage. Portland: Oregon Health Sciences University; 1997.

15 Wagner A, Jensen C, Snebye A, Rasmussen TB. A prospective comparison of iotrolan and iohexol in lumbar myelography. Acta Radiol. 1994;35:182-185.

16 Skalpe IO, Bonneville JF, Grane P, et al. Myelography with a dimeric (iodixanol) and a monomeric (iohexol) contrast medium: a clinical multicentre comparative study. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:1054-1057.

17 Stacul F, Thomsen HS. Safety profile of new non-ionic contrast media: renal tolerance. Eur J Radiol. 1996;23(suppl 1):S6-S9.

18 Hill JA, Winniford M, Cohen MB, et al. Multicenter trial of ionic versus nonionic contrast media for cardiac angiography: The Iohexol Cooperative Study. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:770-775.

19 White AH. Injection techniques for the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1983;14:553-567.

20 Chen CP, Tang SF, Hsu TC, et al. Ultrasound guidance in caudal epidural needle placement. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:181-184.

21 Eichenberger U, Greher M, Kapral S, et al. Sonographic visualization and ultrasound-guided block of the third occipital nerve. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:303-308.

22 Gruber H, Glodny B, Bodner G, et al. Practical experience with sonographically guided phenol instillation of stump neuroma: predictors of effects, success, and outcome. Am J Radiol. 2008;190:1263-1269.

23 Rydevik BL, Cohen DB, Kostuik JP. Controversy: spine epidural steroids for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1997;22:2313-2317.

24 Sibell DM, Fleisch JM. Interventions for low back pain: what does the evidence tell us? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2007;11:14-19.

25 Arden NK, Price C, Reading I, et al. A multicentre randomized controlled trial of epidural corticosteroid injections for sciatica: the WEST Study. Rheumatology. 2005;44:1399-1406.

26 Rowlingson JC. Epidural steroids: do they have a place in pain management? Pain Forum. 1994;3:20-27.

27 Weishaupt D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. MR imaging of the lumbar spine: prevalence of intervertebral disk extrusion and sequestration, nerve root compression, end plate abnormalities, and osteoarthritis of the facet joints in asymptomatic volunteers. Radiology. 1998;209:661-666.

28 Goupille P, Jayson MI, Valat JP, Freemont AJ. The role of inflammation in disk herniation-associated radiculopathy. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1998;28:60-71.

29 McCarron RF, Wimpee MW, Hudkins PG, Laros GS. The inflammatory effect of nucleus pulposus: a possible element in the pathogenesis of low-back pain. Spine. 1987;12:760-764.

30 Saal JS, Franson RC, Dobrow R, et al. High levels of inflammatory phospholipase A2 activity in lumbar disc herniations. Spine. 1990;15:674-678.

31 Koch H, Reinecke JA, Meijer H, Wehling P. Spontaneous secretion of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) by cells isolated from herniated lumbar discal tissue after discectomy. Cytokine. 1998;10:703-705.

32 Coppes MH, Marani E, Thomeer RT, Groen GJ. Innervation of “painful” lumbar discs. Spine. 1997;22:2342-2349.

33 Hwang SM, Kang YC, Lee YB, et al. The effects of epidural blockade on the acute pain in herpes zoster. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1359-1364.

34 Manabe H, Dan K, Hirata K, Hori K, et al. Optimum pain relief with continuous epidural infusion of local anesthetics shortens the duration of zoster-associated pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:302-308.

35 Thomas E, Cyteval C, Abiad L, et al. Efficacy of transforaminal versus interspinous corticosteroid injection in discal radiculalgia: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:299-304.

36 Ackerman WE, Ahmad M. The efficacy of lumbar epidural spread injections in patients with lumbar disc herniations. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1217-1222.

37 Bogduk N. Epidural steroids. Spine. 1995;20:845-848.

38 Renfrew DL, Moore TE, Kathol MH, et al. Correct placement of epidural steroid injections: fluoroscopic guidance and contrast administration. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:1003-1007.

39 Johnson BA, Schellhas KP, Pollei SR. Epidurography and therapeutic epidural injections: technical considerations and experience with 5334 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:697-705.

40 Derby R, Bogduk N, Kine G. Precision percutaneous blocking procedures for localizing spinal pain. Part 2. The lumbar neuraxial compartment. Pain Digest. 1993;3:175-188.

41 Dunbar SA, Manikantan P, Philip J. Epidural infusion pressure in degenerative spinal disease before and after epidural steroid therapy. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:417-420.

42 Carette S, Leclaire R, Marcoux S, et al. Epidural corticosteroid injections for sciatica due to herniated nucleus pulposus. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1634-1640.

43 Buchner M, Zeifang F, Brocai DR, Schiltenwolf M. Epidural corticosteroid injection in the conservative management of sciatica. Clin Orthop. 2000;375:149-156.

44 Hooten WM, Kinney MO, Huntoon MA. Epidural abscess and meningitis after epidural steroid corticosteroid injection. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:682-686.

45 Moran R, O’Connell D, Walsh M. The diagnostic value of facet joint injections. Spine. 1988;13:1408-1410.

46 Esses SI, Moro JK. The value of facet joint blocks in patient selection for lumbar fusion. Spine. 1993;18:185-190.

47 Carette S, Marcoux S, Truchon R, et al. Controlled trial of corticosteroid injections into facet joints for chronic low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1002-1007.

48 Galiano K, Obwegeser AA, Bodner G, et al. Ultrasound guidance for facet joint injections in the lumbar spine: a computed tomography-controlled feasibility study. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:579-583.

49 Mayer TG, Robinson R, Pegues P, et al. Lumbar segmental rigidity: can its identification with facet injections and stretching exercises be useful? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:1143-1150.

50 Bogduk N, Long DL. The anatomy of the so-called “articular nerves” and their relationship to facet denervation in the treatment of low-back pain. J Neurosurg. 1979;51:172-177.

51 Leclaire R, Fortin L, Lambert R, et al. Radiofrequency facet joint denervation in the treatment of low back pain: a placebo-controlled clinical trial to assess efficacy. Spine. 2001;26:1411-1417.

52 Cohen SP, Bajwa ZH, Kraemer JJ, et al. Factors predicting success and failure for cervical facet radiofrequency denervation: a multi-center analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:495-503.

53 van Wijk RM, Geurts JW, Lousberg R, et al. Psychological predictors of substantial pain reduction after minimally invasive radiofrequency and injection treatments for chronic low back pain. Pain Med. 2008;9:212-221.

54 Stovner LJ, Kolstad F, Helde G. Radiofrequency denervation of facet joints C2-C6 in cervicogenic headache: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:821-830.

55 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Bogduk N. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy in the treatment of cervical zygapophysial joint pain: a caution. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:732-739.

56 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, et al. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721-1726.

57 McDonald GJ, Lord SM, Bogduk N. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with cervical radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:6168.

58 McLain RF. Mechanoreceptor endings in human cervical facet joints. Spine. 1994;19:495-501.

59 Beaman DN, Graziano GP, Glover RA, et al. Substance P innervation of lumbar spine facet joints. Spine. 1993;18:1044-1049.

60 Ashton IK, Ashton BA, Gibson SJ, et al. Morphological basis for back pain: the demonstration of nerve fibers and neuropeptides in the lumbar facet joint capsule but not in ligamentum flavum. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:72-78.

61 Ahmed M, Bjurholm A, Kreicbergs A, et al. Sensory and autonomic innervation of the facet joint in the rat lumbar spine. Spine. 1993;18:2121-2126.

62 Indahl A, Kaigle A, Reikeras O, et al. Electromyographic response of the porcine multifidus musculature after nerve stimulation. Spine. 1995;20:2652-2658.

63 Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Multifidus muscle recovery is not automatic after resolution of acute, first-episode low back pain. Spine. 1996;21:2763-2769.

64 McCulloch JA. Percutaneous radiofrequency lumbar rhizolysis (rhizotomy). Appl Neurophysiol. 1976-1977;39:87-96.

65 Wilde VE, Ford JJ, McMeeken JM. Indicators of lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain: survey of an expert panel with the Delphi technique. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1348-1361.

66 Barnsley L, Lord S, Bogduk N. Comparative local anesthetic blocks in the diagnosis of cervical zygapophysial joint pain. Pain. 1993;55:99-106.

67 Manchukonda R, Manchikanti KN, Cash KA, et al. Facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain: an evaluation of prevalence and false-positive rate of diagnostic blocks. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:539-545.

68 Kline MT, Yin W. Radiofrequency techniques in clinical practice. In: Waldman SD, Winnie AP, editors. Interventional Pain Management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996:167.

69 Dreyfuss P, Schwarzer AC, Lau P, et al. Specificity of lumbar medial branch and L5 dorsal ramus blocks. Spine. 1997;22:895-902.

70 Kline MT. Radiofrequency techniques in clinical practice. In: Waldman SD, Winnie AP, editors. Interventional Pain Management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996:188. 191

71 International Spinal Injection Society (ISIS). Standards for the performance of procedures involving spinal injection. Available at www.spinalinjection.com/ISIS/standard/standl.htm

72 Rocco AG, Palombi D, Raeke D. Anatomy of the lumbar sympathetic chain. Reg Anesth. 1995;20:13-19.

73 Ackerman WE, Zhang JM. Efficacy of stellate ganglion blockade for the management of type 1 complex regional pain syndrome. South Med J. 2006;99:1084-1088.

74 Tran KM, Frank SM, Raja SN, et al. Lumbar sympathetic block for sympathetically maintained pain: changes in cutaneous temperatures and pain perception. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:1396-1401.

75 Stanton-Hicks M, Kaigle A, Reikeras O, Holm S. Complex regional pain syndromes: guidelines for therapy. Clin J Pain. 1998;14:155-166.