Chapter 43 Management of Neurological Disease

How an experienced neurologist uses the history of the patient’s illness, the neurological examination, and investigations to diagnose neurological disease is discussed in Chapters 1 and 31. This chapter presents some general principles guiding the management of neurological disease. Chapters 44 to 48 cover individual areas of neurological management such as pain management, neuropharmacology, intensive care, neurosurgery, and neurological rehabilitation. Details about the management of specific neurological diseases are presented in Chapter 49, Chapter 50, Chapter 51, Chapter 52, Chapter 53, Chapter 54, Chapter 55, Chapter 56, Chapter 57, Chapter 58, Chapter 59, Chapter 60, Chapter 61, Chapter 62, Chapter 63, Chapter 64, Chapter 65, Chapter 66, Chapter 67, Chapter 68, Chapter 69, Chapter 70, Chapter 71, Chapter 72, Chapter 73, Chapter 74, Chapter 75, Chapter 76, Chapter 77, Chapter 78, Chapter 79, Chapter 80, Chapter 81, Chapter 82 . Many aspects of management are common to all neurological disorders; these management considerations are the subject of this chapter.

Principles of Neurological Management

As in all medical disciplines, many neurological diseases are, at present, “incurable.” This does not mean, however, that such diseases are not treatable and that nothing can be done to help the patient. Help that can be provided short of curing the disease ranges from treating the symptoms, to providing support for the patient and family, to end-of-life care (Box 43.1). Healthcare professionals are so committed to the scientific understanding of diseases and their treatment that the natural tendency of the clinician is to feel guilty when confronted with a patient with an incurable disease. The number of neurological diseases that are curable or arrestable is constantly expanding thanks to research.

Unfortunately, a physician who is fixated on the need to cure disease may simply strive to make the diagnosis of an as-yet incurable disease and then give no thought to patient management. Such a physician will tell the patient that he or she has an incurable disease, so coming back for further appointments is pointless (“diagnose and adios”). The aphorism “To cure sometimes, to relieve often, to comfort always” originated in the 1800s with Dr. Edward Trudeau, founder of a tuberculosis sanatorium. Any other attitude not only is an abrogation of the physician’s responsibility to care for the patient, but also leaves the patient without the many modalities of assistance that can be provided even to those with incurable diseases. The neurologist who accepts the responsibility for treating the patient will review with the patient and family all the issues listed in Box 43.1. In fact, it usually is necessary to spend more time with the patient with an incurable disease than with one for whom effective treatment is available. In addition to providing all practical help available, the compassionate neurologist should share the grief and provide consolation for the patient and family; both are essential aspects of patient management.

Goals of Treatment

Arresting an Attack

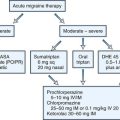

Many neurological diseases cause episodic attacks. These include strokes, migraine, MS, epilepsy, paroxysmal dyskinesias, and periodic paralyses, and in some of these diseases, treatment may prevent or halt the attacks. Although it does not cure the underlying disease, aborting the attacks is of great help to the patient. Triptan-class drugs generally arrest a migraine, and valproate, a beta-blocker, or a calcium channel blocker will reduce the frequency of the attacks (see Chapter 69). Status epilepticus usually can be arrested by intravenous antiepileptic drugs, and the frequency of epileptic attacks can be reduced by the use of chronic oral anticonvulsant drugs (see Chapter 67). Intravenous and intraarterial thrombolytics may terminate and potentially reverse an otherwise disastrous “brain attack” (cerebral ischemia) (see Chapter 51A).

Slowing Disease Progression

Examples of treatments that slow the progress of neurological disease are numerous. A malignant cerebral glioma is almost universally fatal, but high-dose corticosteroids, neurosurgical debulking, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy may slow tumor growth and prolong survival (see Chapters 52E and 52F). The β-interferons, glatiramer, natalizumab, or mitoxantrone may reduce relapses and slow the progress of MS (see Chapter 54). Liver transplantation in familial amyloid polyneuropathy may slow or arrest disease progression (see Chapter 76). Riluzole may slow the progress of ALS (see Chapter 74). Despite many efforts to slow the progression of Parkinson disease (PD), no neuroprotective therapy has proved to be effective, although certain monoamine oxidase B inhibitors and dopamine agonists delay the onset of levodopa-related motor complications.

Relieving Symptoms

Symptomatic treatment is available for many neurological diseases. Relief of pain, although not curative, is the most important duty of the physician and can be accomplished in many ways (see Chapter 44). Baclofen and tizanidine can reduce spasticity, particularly in spinal cord disease, without affecting the disorder causing it. Injections of botulinum toxin provide marked relief in patients with dystonia, spasticity, and other disorders manifested by abnormal muscle contractions. High-dose corticosteroid therapy reduces the edema surrounding a brain tumor, temporarily relieving headache and neurological deficits without necessarily affecting tumor growth. In PD, dopaminergic drugs partly or completely relieve symptoms for a period, without affecting the progressive degeneration of substantia nigra neurons (see Chapter 71). The physician-patient relationship and the placebo response both are important tools used by the experienced neurologist in helping to relieve a patient’s symptoms.

Circumventing Functional Disability

Neurological rehabilitation is the discipline that concentrates on restoration of function (see Chapter 48). Physical and occupational therapy help the patient to strengthen weak muscles, retrain the nervous system to compensate for lost function, increase mobility, and reduce spasticity. Some authorities believe that cognitive or behavioral therapy may similarly reeducate undamaged cortical areas to compensate for the effects of brain injury and stroke. Orthopedic procedures can be beneficial for rehabilitation; transfer of the tibialis posterior tendon to the dorsum of the foot can correct a footdrop in appropriate cases. Surgical release of Achilles tendon and iliotibial contractures in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy can delay the loss of ability to walk by 2 years or more.

The range of options available to help a patient with a severe, chronic neurological disease can be illustrated by reference to ALS. In the early stages, the patient may simply need enlarged handles on tools, pens, and utensils to compensate for a weak hand grip, or a cane to help with walking. Later, the patient may need a wheelchair and home adaptation. Speech therapy, a communication board, or a computer with specialized software can help when speech is severely impaired. Weight loss and choking from dysphagia may necessitate a percutaneous gastrostomy. An incentive spirometer and an artificial cough machine can protect respiratory function (see Respiratory Failure later in the chapter). If the patient decides not to use a ventilator, end-of-life counseling and hospice care are needed.

Principles of Symptom Management

Treatment of Common Neurological Symptoms

Several symptoms, such as pain, weakness, dysphagia, and respiratory failure, are common to many different neurological diseases. This section outlines the general principles that govern management of these symptoms. Chapters 44, 45, and 48 provide more complete discussions. Specific treatment for individual diseases is found in the relevant chapters in Volume II of this book.

Pain

The first step in pain management is to diagnose the source of the pain and assess the prognosis of the disease (see Chapter 44). Consider, for example, a patient with incapacitating pain in one leg from carcinoma infiltrating the lumbosacral plexus on one side. This patient’s life expectancy may be measured in weeks or months, and progressive plexus damage will produce leg paralysis. Destructive procedures and narcotics are justified in this situation. Surgical interruption of pain pathways is considered the final choice to relieve pain from carcinomatous infiltration of the lumbosacral plexus. Such procedures include surgical or chemical posterior rhizotomy, contralateral anterolateral spinothalamic tractotomy in the midthoracic region, and stereotactic contralateral thalamotomy. Tachyphylaxis for narcotics can occur, and the oral dose of narcotics required to control pain may rise rapidly in patients who live for several months. This does not appear to occur with morphine administered by an intrathecal or epidural spinal catheter using a subcutaneous infusion pump.

Weakness

The management of weakness, considered more fully in Chapter 48, is a major component of neurological rehabilitation. Choice of treatment depends on the extent, severity, and prognosis of the patient’s weakness. For example, weakness of flexion of the ankle due to Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease may be treated with a triple arthrodesis of the foot. Such a procedure, however, would not be appropriate to overcome the footdrop caused by a more rapidly progressive condition such as ALS. For such patients, an ankle-foot orthosis is best. Most neuromuscular conditions are benefited by exercise, although fatigue limits the amount of exercise that can be tolerated. Myasthenia gravis, however, is worsened by exercise. Weakness due to upper motor neuron disease can be addressed by physical and occupational therapy to promote the use of alternative neuronal pathways. Medications such as baclofen, tizanidine, and botulinum toxin injections reduce spasticity and may improve function in upper motor neuron disorders.

Respiratory Failure

Respiratory failure may develop in several neurological diseases (Box 43.2; see also Chapter 45). Patients with chronic neuromuscular diseases often complain of respiratory distress when they are close to respiratory failure. Patients with a weak diaphragm experience dyspnea when lying supine, because the abdominal contents prolapse into the chest, thereby lowering the patient’s vital capacity and tidal volume. A neurologist or a pulmonary specialist who is relatively inexperienced in neurological problems affecting respiration may underestimate the warning signs of potentially fatal respiratory failure. This is particularly true in myasthenia gravis and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Blood gas measurements do not change until late in the development of respiratory failure in chronic neuromuscular diseases. By the time evidence of hypoxia and hypercapnia appears in the blood, the patient may be bordering on acute respiratory collapse. Reduced vital capacity, patient distress, and a good knowledge of the disease are better ways of judging impending respiratory failure. A patient with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and a vital capacity of 600 mL may survive for several years without dyspnea. A patient with myasthenia gravis who has a vital capacity of 1200 mL but is anxious, sweating, and complaining of dyspnea is at serious risk for the development of fatal respiratory paralysis. With borderline respiratory function, sleep or sedation may produce carbon dioxide retention and narcosis, leading to further respiratory suppression and death.

Box 43.2 Types of Neurological Disease Associated with Respiratory Failure

Memory Impairment and Dementia

Alzheimer disease is the most common cause of progressive impairment of memory and dementia, and only symptomatic care is possible, which includes anticholinesterase inhibitors. Some causes of progressive dementia are curable (see Chapter 66), and their recognition important. Even if no specific curative treatment is available, the experienced neurologist can provide essential advice to the family of a patient with a condition like Alzheimer disease on how to anticipate problems and minimize them. This includes helping the patient to make shopping lists and checklists of things to do before leaving the kitchen or the house and before going to bed. For a period, these measures can prevent the patient from leaving the house unlocked, or from forgetting about a pot boiling on the stove. Inevitably, the patient will have difficulty managing a checkbook, and a family member should take over money management before financial disaster occurs. The patient eventually will need either a live-in companion or must move in with a family member or into a nursing home. Much of the neurologist’s efforts are directed toward helping the patient and family circumvent problems and adjust to expected changes. Family members need access to books and publications by foundations and support groups such as the Alzheimer’s Disease Association.

Palliation and Care of the Terminally Ill Patient

Palliative care starts from the earliest stage of the doctor-patient relationship. Pain, depression, and anxiety are the three major symptoms that require palliation. The treatment of pain is considered in Chapter 44. Psychological reactions are treated with a range of pharmacological agents, including benzodiazepines for anxiety, neuroleptics for psychotic symptoms, and an ever-increasing list of medications for depression. The psychological support for the patient and family provided by the doctor, however, usually is more important than pharmacological therapy. The experienced neurologist provides help to the patient and family by drawing on lessons learned from treating many similar patients. Even though the disease and its effects cannot be arrested, the neurologist can help ease the emotional burden. When possible, the neurologist should discuss each new phase of the disease with the patient and family before it occurs. No patient likes to hear of impending deterioration, but if the neurologist clarifies the importance of anticipation, the patient is reassured that the doctor is ready to deal with change, when and if it occurs.

Genetic Counseling

Approximately 1 in 10 neurological conditions has a genetic basis. Rapid advances in molecular genetics require that the neurologist keep abreast of the many diseases that can be diagnosed by genetic testing (see Chapter 40). Genetic counseling should take into account the limitations and pitfalls of the various commercially available DNA tests, however, and the assistance of an experienced medical geneticist is invaluable. A parent with a neurological disease commonly fears that the disease will pass to the children. Hence, if a disease has no hereditary component, the parent should be reassured. If the disease has a hereditary tendency, the risk to offspring must be discussed. For instance, the chance of occurrence of MS in the offspring of a patient with MS is higher than that in the general population, but it is still only about 3%.