Chapter 9 Management of Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia may be defined as enlargement of the male breast. However, from a surgical point of view, it may be more helpful to view the condition as a persistent enlargement of the breast as transient breast enlargement during puberty is actually a normal finding occurring in up to 65% of normally developing adolescent boys. It is this persistence that generally motivates patients to seek treatment as the enlarged breast can create a significant contour deformity when compared to the appearance of a normal male chest contour. From a therapy standpoint, there are three main presentations of gynecomastia that require slightly different approaches when it comes to designing an appropriate course of treatment.

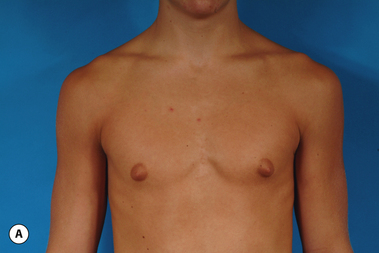

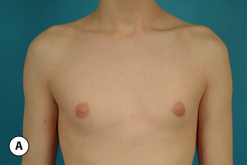

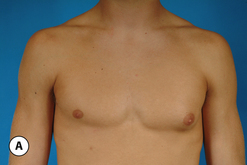

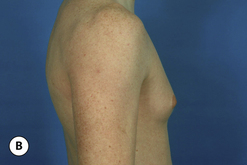

The hallmark finding in patients with adolescent gynecomastia is a firm, fibrous mass of tissue that develops directly under the areola (Figure 9.1). This mass can be variable in size and can herniate through the elastic areolar skin, resulting in a very obvious contour abnormality. In addition, it is not uncommon for a surrounding fibrofatty stroma of varying volume to develop in concert with the subareolar mass. The magnitude of this fatty overgrowth is directly related to the body habitus of the patient with more obese patients tending to demonstrate a more dramatic increase in the size of the breast (Figure 9.2). Along with the general breast overgrowth can be noted an excess of skin to the point that actual ptosis of the breast mound can be noted (Figure 9.3). Finally, as a result of the enlarged subareolar breast bud along with the general increase in the volume of the breast, the diameter of the areola can increase significantly, all of which combines to create a decidedly abnormal breast contour for a young adolescent male (Figure 9.4).

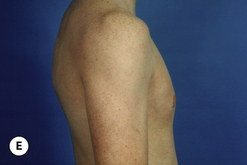

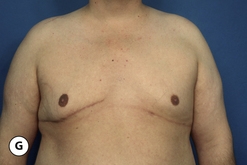

Senescent gynecomastia – Alternatively, persistent gynecomastia can develop later in life, generally after the age of 50. Here the nature of the enlarged breast is slightly different as the fibrofatty component of the breast tends to be more predominant (Figure 9.5). Generally, the patient will experience a gradual enlargement of the breast that develops over the course of a year or more and this enlargement will often be tied to an overall gain in weight. A subareolar thickening may be noted but the enlargement of the breast is more diffuse in the older male and often there will be associated fatty deposition under the arm and higher up onto the chest wall toward the clavicle. Again, a change in the ratio of the sex hormones may be responsible for this change in body habitus with the natural decline in circulating levels of testosterone that is noted with advancing age being the likely etiologic factor. These patients generally seek treatment in an effort to restore a more normal overall male chest wall contour.

One specific variant of pathologic gynecomastia is that which occurs as a result of exogenous hormone administration. Gynecomastia has been noted to develop as a result of recreational drug use with marijuana being widely recognized as a common cause of the condition. Also, young males involved in the sport of bodybuilding will sometimes develop a very discrete and fibrous subareolar type of gynecomastia secondary to the use of either injectable or oral testosterone or testosterone precursor-like drugs, along with a whole host of other anabolic steroid type substances. Screening for any history of drug use becomes particularly important in these types of patients in order to clarify the etiology of the condition and, as well, to develop an appropriately targeted treatment plan. Specifically, it is highly advisable that such patients discontinue all exogenous drug use prior to undergoing any form of surgical treatment.

Indications for Treatment

Although pain may occasionally be noted in patients with gynecomastia, it is most certainly the altered chest contour along with the emotional sequelae of the condition that motivates nearly all patients to seek treatment. This is particularly true in adolescent males. It must be recognized that the teenage years are a vitally important time period during which significant social and emotional growth occurs. In these patients, even modest cases of gynecomastia can result in social withdrawal and avoidance of any situation that will require the patient to take his shirt off. As a result, important social activities including participation on athletic teams, swimming and even casual interaction with other peers are avoided secondary to the embarrassment the patient feels about his appearance. Once gynecomastia is recognized, it is reasonable to delay definitive surgical excision for up to 2 years or more, as some patients will spontaneously regress on their own as their internal hormonal environment stabilizes. Typically, this will occur by the age of 15. However, should any degree of social withdrawal become noticeable as a result of the condition, it is entirely reasonable and recommended to proceed with surgical treatment.

Special mention must be made concerning those patients who present with gynecomastia in association with significant obesity. Certainly, in these patients, the major cause of the enlarged breast contour is the excess general fatty accumulation. Although some stromal overgrowth in the subareolar region may be present, it is generally overwhelmed by the significant amount of fat present in the breast. This combination can often lead to surprising levels of breast development that can result in significant breast ptosis (Figure 9.6). Therefore, while any first line therapy would best be directed primarily at weight loss, the adverse effect such breast development can have on a patient who is likely already struggling with body image issues can be quite damaging. For this reason, it is very reasonable and even advisable to proceed with surgical correction of gynecomastia in the obese. Normalizing the contour of the chest wall may well allow the patient to make appropriate lifestyle changes later in life as he matures that will lead to a healthier body composition.

Surgical Technique – General Concepts

Volume Reduction

Direct excision

The procedure can be performed under local anesthesia with intravenous sedation or, conversely, general anesthesia can be used. The proposed incision as well as the surrounding breast flaps are infiltrated with a dilute solution of lidocaine with epinephrine to aid in hemostasis and, as well, allow clearer identification of tissue planes and, in particular, the plane between the fibrous breast bud and the overlying fat associated with the breast flaps. An incision is made along the lower border of the areola just at the junction of the pigmented areolar skin with the non-pigmented skin of the lower breast. Typically, this incision heals in an imperceptible fashion and is well tolerated by most patients. The incision extends along the entire lower half of the areolar border to allow adequate exposure for removal of the fibrous subareolar tissue. Around the inferior lower half of the breast, the fibrous button of tissue is dissected free from the surrounding breast flaps until the limits of the fibrous mass that were marked preoperatively are reached. Every effort is made to leave behind any fat that may be associated with the flaps as this fat can soften the resulting breast contour and help guard against the creation of a central depression after removal of the fibrous component. Centrally, the fibrous bud is then sharply transected such that approximately 5–10 mm of evenly layered fibrous tissue remains attached to the underside of the areola. This is a sculpting maneuver designed to prevent over thinning of the areola resulting in a central depression. It must be smoothly performed and may extend slightly past the margins of the areola on all sides. It is generally necessary to do this because there is no fat directly under the areola and, if the subareolar breast bud is removed at the dermal level, a step off will be created at the junction of the areola with the surrounding thicker breast flaps creating a postoperative contour deformity. Once the fibrous mass has been smoothly dissected free from the areola, dissection is resumed superiorly again leaving behind any fat that might remain on the breast flap. Finally, the fibrous mass is freed from any attachments that remain to the pectoralis major muscle and removed. If any irregularities in the contour of the breast persist, scissor dissection can be used further to thin the peripheral flaps to create a smooth contour. With removal of the subareolar tissue, it can commonly be observed that the areola retracts to a more normal diameter now that the mass effect of the underlying breast bud has been removed. Hemostasis is assured and the wound closed in layers with interrupted inverted 4-0 absorbable monofilament sutures followed by a running subcuticular of the same material. At this point, the contour of the breast should be smooth with no high points or depressions. Dermabond is applied to the skin incision followed by an Opsite dressing. A support vest is worn for several weeks to assist in smoothly and gently compressing the breast flaps against the chest wall. Suture ends are clipped at 1 week and full return to activity is allowed at 4–6 weeks. With careful attention to dissection planes and, in particular, accurate and even thinning of the subareolar fibrous layer, complete correction can be achieved on a consistent and reliable basis (Figures 9.7, 9.8).

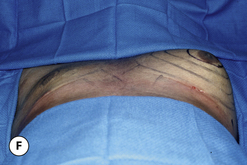

Liposuction

As noted with direct excision, the procedure can be performed either under local tumescent anesthesia with intravenous sedation or, conversely, under general anesthesia. Although there are many options for incision placement, it is my preference once again to utilize the junction of the pigmented areolar skin with the non-pigmented chest wall skin as a camouflage that hides the subsequent scar very well. Conversely, additional incisions can be made anywhere along the inframammary fold, or laterally along the chest wall. These incisions can be useful in thinning the central quadrant of the breast due to the fact that a better mechanical advantage is afforded to the passage of the cannula from an area remote to the area to be treated. Once incision placement has been finalized, small stab incisions are made and tumescent fluid is added to the breast. It is helpful to mark this area preoperatively to ensure that the removal of fat is feathered appropriately with an eye toward creating smooth contours under the arm, superiorly along the upper chest and inferiorly below the fold. A usual tumescent fluid mixture is utilized consisting of 40–60 cc of 1% lidocaine with a 1:100 000 epinephrine concentration added to one liter of normal saline. Typically, one liter of fluid is added to each breast or until the consistency of the tumesced tissues becomes firm. Then, using a 3–4 mm cannula, standard liposuction is performed evenly removing tissue from the area that was marked preoperatively. Particular attention is directed in the subareolar area where external pinching compression with the fingers of the opposite hand can be used to help drive the dense fat interspersed within the subareolar fibrous network into the tip of the cannula. This can help adequately debulk this area and ensure that a residual subareolar bulge will not be present postoperatively. In difficult cases, it can be advantageous to approach the breast from two different directions, to maximize the removal of fat in an even and controlled fashion. Note is made of the amount of tumescent fluid instilled and the amount of liposuction aspirate removed from each side to ensure symmetry. Each incision is closed in a standard fashion and dressed with Dermabond and Opsite. A support vest is worn for 2 weeks and return to full activity is allowed at 4–6 weeks (Figure 9.9).

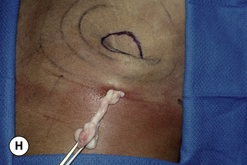

Combination approach

Typically, most gynecomastia patients will present with a firm subareolar fibrous breast bud in combination with a peripherally located supporting fibrofatty stroma. To recontour both the breast and the chest wall appropriately, it is necessary to address each of these anatomic features. A common error is to rely simply on liposuction to recontour the breast and leave the subareolar fibrous component intact. If the fibrous portion is of sufficient size, it will cause a persistent areolar protrusion that can become noticeable once the swelling associated with the procedure resolves and this persistent contour deformity can be a source of patient dissatisfaction.

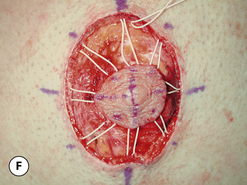

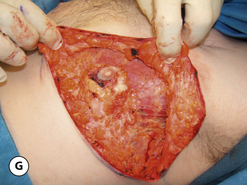

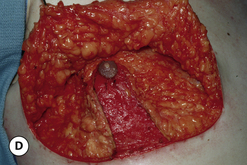

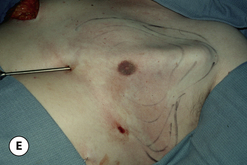

The operative planning and execution proceed quite simply as described. Initially, the breast is tumesced through stab incisions located around the areola or peripherally through the fold or lateral chest wall. Liposuction is used to definitively recontour the peripheral margins of the breast up to the area centrally where the fibrous component is located. Every effort is made to honeycomb through the dense subareolar area as much as possible to remove any fat that may be dispersed within. Once the peripheral margins have been appropriately treated and no further fat can be easily removed from the subareolar area, the mass effect of this remaining fibrous portion must be assessed, not only visually but also via palpation. If any suggestion of a mass effect is noted under the areola, it is highly recommended that the remaining fibrous tissue be thinned to prevent a persistent contour deformity from developing. While it is possible to open up the inferior portion of the areola as described previously to allow direct removal of the fibrous component, it is also possible to use a scar limiting approach called the ‘pull through’ technique. Here, a small 1 cm incision is made at the junction of the inferior areola with the chest wall skin in a way that exposes the glistening white fibrous component underneath. By grasping this tissue with a heavy clamp, it can be pulled through the incision and debrided until the desired contour correction has been achieved. This maneuver is facilitated by the previously performed liposuction as the honeycomb effect created by the passage of the cannula through the fibrous mass assists in breaking up the architectural integrity of the mass, allowing it to be pulled out in strands. Debridement is continued until a smooth subareolar contour has been obtained (Figures 9.10, 9.11). It is also possible to approach the fibrous breast bud from a remote incision location laterally or inferiorly along the inframammary fold. Using an incision located away from the area of the areola can at times assist in more smoothly contouring the subareolar area than when the incision is located at the areolar junction (Figure 9.12). Whatever approach is used, the pull through technique offers advantage not only in limiting the scar, but also has been quite useful in preventing inadvertent over-resection in the subareolar area with the creation of the classic ‘saucer’ deformity. It is a very useful approach in treating patients who require a combination procedure.

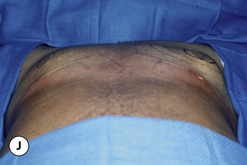

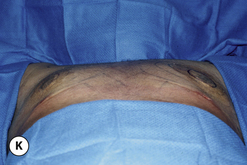

Skin Retailoring

As a general rule, most patients who undergo treatment for gynecomastia will not require any reduction at all in the remaining skin envelope of the breast as the propensity of the breast and chest wall skin to retract is significant. It is only in the minority of patients that this retraction is insufficient to create a normal chest wall contour. It is for this reason that many surgeons are reluctant to proceed with a primary skin envelope reduction at the same time that the volume is reduced and instead apply a staged strategy to allow the skin retraction to proceed and then later reassess the need for skin envelope reduction (Figure 9.13). Using this strategy, an aesthetic result can very often be achieved using a less aggressive skin envelope reducing technique with fewer scars than was initially thought. This staged approach is recommended for patients who present with mild skin redundancy as the reduction in scar burden that occurs when no skin envelope reducing procedure is required is a very significant advantage.

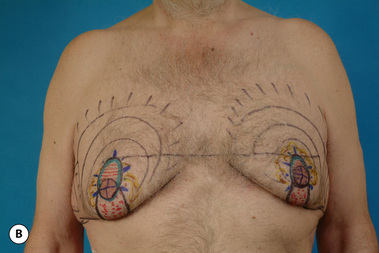

In those patients who present with extreme skin laxity, skin with poor elasticity or in those patients who present with a redundant skin envelope after primary volume reduction, a skin reducing procedure is indicated. The operative planning for these patients proceeds in a fashion very similar to the approach used for women seeking mastopexy with the major goals of the procedure being the removal of the excess skin, lifting of the NAC position, reshaping of the breast and chest wall contour and the creation of the least amount of cutaneous scar possible.

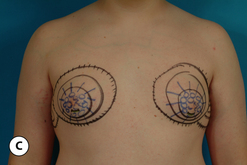

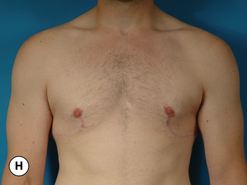

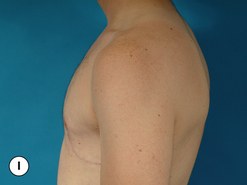

Periareolar pattern

The periareolar pattern is indicated in those patients who will require a lifting of the position of the NAC, a small reduction in the skin envelope, or both. The pattern is applied as in any mastopexy with the top of the periareolar incision planned to extend no more than 2–3 cm above the inframammary fold as, in a male, the position of the NAC is naturally located slightly lower than it is in a female. The remainder of the pattern is drawn in a circular pattern around the areola, removing as much skin as necessary to tighten the skin envelope and create a smooth chest wall contour. Note that the usual practice used in females of limiting the amount of skin removed medially and laterally is suspended as nearly all of the breast volume will be removed and no accommodation is needed for creating an aesthetic breast shape. At the time of surgery, the incision in the areola is drawn in a circular fashion with the areola under stretch at a maximum diameter of 3 cm, a measurement much less than that commonly used in women. In primary cases of skin envelope reduction, the lower portion of the periareolar incision can be used to access the breast to allow excision of the fibrous component to be performed as needed. Once completed, the intervening skin is de-epithelialized and the resulting defect is managed with a periareolar purse string suture. It is my practice to use the interlocking Gore-Tex technique to limit the amount of postoperative areolar spreading that occurs. The dermis of the periareolar defect is not divided as it is in traditional mastopexy technique in females because the subareolar area is typically thinned significantly in males and dividing the dermis could cause vascular embarrassment to the NAC with possible ischemia and necrosis being the result. In cases of delayed periareolar skin envelope reduction, the dermis can be divided and a dermal shelf created as is done in standard periareolar purse string technique due to the fact that revascularization of the supporting tissues under the NAC has occurred and the potential for creating ischemia by dividing the dermis is significantly reduced. By dividing the dermis, less stress is placed on the periareolar closure due to less tissue bunching and the tendency for the areolar diameter to spread postoperatively is reduced. In cases of modest skin excess, the periareolar technique can allow a contoured chest wall to be created with only a minimum of scar that tends to be well accepted by many patients. Should the patient have any tendency toward hair growth in the chest area, a significant camouflage effect can be the result, making the procedure all the more acceptable (Figure 9.14).

Circumvertical pattern

While the periareolar approach can be quite useful in elevating the position of the NAC and mildly reducing the skin envelope, it does become somewhat limited as an effective skin envelope reducing technique in patients with a pronounced skin excess. Typically, such patients will not only require reduction of the skin envelope in the vertical direction, but will also need reduction in the horizontal direction. This narrowing of the base diameter of the skin envelope is often required to tighten the skin envelope sufficiently and create a normal male chest wall contour. The application of the vertical component proceeds very similarly in males as compared to females. After the majority of the excess breast volume has been reduced using liposuction, the redundant lower pole skin is plicated with staples intraoperatively in conjunction with the application of the periareolar pattern and the patient is placed in the upright position to assess the effect. Additional revision using the tailor stapling technique is used to create the desired result. The staple line is marked, the staples removed and the intervening skin is de-epithelialized. The lateral portion of the vertical incision line can be divided just through the dermis to ease the tension on the vertical closure. This incision can also be used as an access portal to the breast to facilitate internal dissection as needed, and any remaining fibrous tissue present under the areola can then be excised as in the direct excision technique described previously. The pedicle supporting the NAC can be thinned as needed, being certain to leave at least 1 cm of tissue attached to the underside of the NAC as well as the pedicle itself. Near the inframammary fold (IMF), the pedicle can be left a bit thicker to avoid inadvertently diminishing the blood supply to the NAC. After the breast volume has been appropriately reduced, the vertical incision is closed with interrupted and running 4-0 absorbable monofilament sutures. The periareolar portion is re-de-epithelialized as needed to create a perfectly round areolar closure and the interlocking Gore-Tex technique is applied as before. In cases of delayed skin envelope reduction, no additional internal dissection is required and the application of the circumvertical pattern involves simple tailor staple reshaping of the chest wall contour, de-epithelialization of the redundant skin, release of the dermis as needed to allow tension free closure and application of the interlocking Gore-Tex suture. As before, the dermis can be released with confidence as the skin flaps and NAC will demonstrate adequate vascularity secondary to revascularization from the underlying pectoralis major muscle. The circumvertical skin pattern is a powerful short scar technique for restoring a normal chest wall contour in patients with gynecomastia who present with significant redundancy or laxity in the skin envelope (Figures 9.15, 9.16).

Horizontal pattern

In cases of significant skin redundancy, a horizontally oriented pattern with no vertical component can be used to remove the excess skin and reshape the breast. Using this strategy, the blood supply to the NAC is provided using an inferior pedicle and the surrounding tissues are smoothly excised to debulk the breast. The pedicle itself can be mildly undermined as desired to ensure a smooth chest wall contour. After the breast volume has been reduced, the horizontal incision is closed and the location for the NAC determined, again keeping in mind that the ideal location in a male is somewhat more inferiorly located than in a female. A circular cutout is made and the NAC is inset into the defect. By placing the resulting scar in the inframammary fold, it becomes less conspicuous as compared to a vertical scar that can be more easily seen running directly down the center of the breast (Figure 9.17).

Complication Management

Residual contour deformity

In patients with gynecomastia, removing the fibrous and fatty components of the breast in such a way that even and contoured flaps are left behind can be a technical challenge. Over-resection of the subareolar fibrous mass can create a central depression under the areola, resulting in an uneven chest wall contour. Also, uneven application of liposuction can create contour irregularities in the periphery of the chest wall. One common area for persistent fatty accumulation, particularly in the obese, is under the arm along the lateral chest wall. Whatever the cause, anything less than a smooth chest contour causes concern for the patient and usually results in revisionary surgery. When planning a revision, it is best to treat the high areas first with specifically targeted liposuction using small cannulas to reduce the magnitude of the deformity. Then should any residual depression be noted, lipofilling is indicated to fill in the contour defect. Standard technique using small aliquots of transplanted fat harvested from the abdomen can be very effective in smoothing out postoperative surface irregularities. Judicious use of these modalities can help restore a smooth chest wall contour when contour irregularities occur after first stage gynecomastia excision.