Chapter 165 Management of Degenerative Lumbar Stenosis and Spondylolisthesis

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Decision Making in Surgical Intervention

There is an overlap of radiologic findings between these two entities that requires further categorization. The differentiation of pure lumbar stenosis from degenerative spondylolisthesis begins with plain radiographs and dynamic lateral flexion and extension x-rays. The patient’s symptoms should correlate with the pathologic anatomy noted on all preoperative imaging studies. Greater than 4 mm of anterior translation of the superior vertebral body on the inferior body constitutes degenerative spondylolisthesis.1 Standing lateral flexion and extension x-rays can provide additional evidence of dynamic instability to supine lateral flexion and extension views. Each level of the lumbar spine can be assessed preoperatively for individual stability based on disc height, angular motion of the end plates, translation as measured on plain radiographs, or fixed or mobile translation as evaluated on dynamic radiographs. Unfortunately, the preoperative assessment of stability loses significance after destabilizing decompressive procedures are performed.

Surgical Intervention

The purpose of any surgical intervention is to decrease pain, improve function, and prevent neurologic deterioration. The goal of surgical decompression is to decompress all of the neural elements that are producing the patient’s symptoms. Degenerative changes can span multiple vertebral levels on imaging studies, but not all levels may be involved in producing the patient’s stenotic symptoms at the time of examination. Neural compression is documented well by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Increased sophistication in the technology and interpretation of MRI scans, with or without supplemental computed tomography (CT) images, has decreased the “mandatory” use of CT-myelography for all surgical patients. Some radiologic facilities supplement MRIs with selected CT cuts through the spine areas where maximal compression has occurred. A CT image better defines the bony architecture of the spinal column, whereas an MRI scan better depicts the soft neural structures. The CT scan also provides information on the extent of the neural compression due to bone involvement. Neural compression is usually due to a reduction of the spinal canal from posterior protrusion of the disc material, hypertrophy of both the facets and ligamentum flavum, and the listhesis.

The lamina, hypertrophic ligamentum flavum, and osteophytic areas of facet joints can all contribute to the stenosis and therefore require removal. The excess ligamentum flavum should be removed prior to or as a part of the facetectomy. Part of the facet joint may be removed by means of undercutting the medial aspects of both facets. Once again, fusion must be considered if greater than 50% of either facet is removed. Decompression is often performed in a caudal to cranial direction, usually to the level of the pedicle of the vertebra below the involved level. This is accomplished in three steps: First, the central canal is decompressed using a high-speed bur and a Kerrison rongeur. Second, both lateral recesses are decompressed by partially removing the medial aspect of each inferior facet, with subsequent undercutting of the respective superior facets. Third and last, a fine instrument, such as a blunt dental tool or a Frazer dural angled elevator, is used to assess the degree of foraminal stenosis as well as the adequacy of foraminal decompression. The final foraminal decompression is performed using a fine Kerrison rongeur placed just dorsal to the nerve root. The neural foramen is adequately decompressed when the nerve root can be gently retracted about 1 cm medially. Visualization of the pars interarticularis must be maintained to avoid excessive bone removal (Fig. 165-1). Constant vigilance is required during this portion of the procedure.

A limited laminectomy has also been described for treating spinal stenosis.2 In this procedure, the central portion of the neural arch is preserved. Thus, the interspinous and supraspinous ligaments remain intact, minimizing spinal instability. Hemilaminectomy is indicated for patients with unilateral stenosis and unilateral symptoms. However, this procedure potentially makes it difficult to decompress the contralateral side or to perform adequate decompression of the ipsilateral foramen. This is due, in part, to the difficulty in angling instruments laterally to enter the foramen in the presence of an intact spinous process and midline ligaments. An alternative to limited laminectomy is a hemilaminotomy procedure, where two hemilaminotomies are performed on the adjacent hemilaminae. Partial facet excision is then performed for greater lateral decompression, as described for hemilaminectomy.

Another published method is a lumbar laminoplasty, a treatment used in active manual workers.3 It is a procedure similar to cervical laminoplasty. Affected spinous processes are removed at the base, and bilateral unicortical grooves are made at the junction of the lamina and facets. The laminae are then split in the midline and the canal is opened. Spinous process or bone allograft is placed between the open laminae and held secure with suture or steel wire through previously made holes in the laminae and grafts. A body cast is mandatory postoperatively for a minimum of 2 weeks to avoid stress on the construct during ambulation.3 This procedure has very limited clinical indications.

Discectomy is generally not required in the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. True herniations are uncommon. However, the surgeon should assess each case for the possibility of a concomitant disc herniation or hard ridge that might compress the root. In the presence of a markedly bulging disc or in the case of a true soft disc herniation that is contributing to significant nerve root compression, a discectomy may be needed. This being said, a discectomy can also cause subsequent spinal instability, because both anterior and posterior elements are sacrificed. In this circumstance, some surgeons recommend arthrodesis at the time of surgery. Spinal stability should be maintained during decompression by preserving both the pars interarticularis and the facet joints. However, in many cases, much of the facet joint might need to be removed for adequate decompression of the involved nerve root.

Surgical Outcome for Spinal Stenosis

Surgical outcome for lumbar spinal stenosis is quite varied. In a prospective, nonrandomized observational cohort study of patients with spinal stenosis followed for 1 year, 55% of surgical patients reported definite improvement. This was in contrast to the nonsurgical patients, of whom only 28% reported a satisfactory outcome.4 In a prospective study of 105 consecutive patients undergoing decompressive laminectomy, a 63% to 67% rate of satisfactory results was reported at 2 years. This result deteriorated to 52% at 5-year follow-up.5 Sixteen percent of these patients underwent reoperation for severe back pain or recurrence of their stenosis (or both) during the 5-year period. Risk factor for poor outcome was correlated to a preoperative duration of symptoms of more than 4 years, significant comorbidity, and preoperative back pain. In another series of 140 patients treated surgically, at an average follow-up of 3 years, 71% reported an improvement in back pain and 82% improvement in leg pain.6 In a longer follow-up of 2.8 to 6.8 years of 88 patients with decompression laminectomy, Katz concluded that 11% of patients had poor results at 1 year.7 This poor quality results later increased to 43% with a reoperation rate of 17% at final follow-up. Again, poor outcome was correlated to preoperative comorbidities and limited decompression. Turner and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of the lumbar stenosis literature and noted a 64% mean proportion of good to excellent results over the long term.8

Most studies indicate that decompression alone is adequate in pure lumbar stenosis without significant spondylolisthesis or other deformity. In a prospective randomized study by Grob and colleagues, 45 patients underwent decompression or decompression with arthrodesis for pure stenosis. There was no significant difference in clinical outcome among patients.9 Overall satisfactory results were 78% for patient-related outcome data in all groups, including decompression without arthrodesis, decompression plus fusion of the most significant stenotic segment, and decompression with arthrodesis of all stenotic levels. They concluded that lumbar spine decompression alone changed the natural history of this disease, with improvement in quality of life. They also determined that arthrodesis is indicated when stenosis is associated with degenerative spondylolisthesis, scoliosis or kyphosis, recurrent stenosis at the same level, stenosis adjacent to a prior fusion, aggressive facetectomy, or need for a disc excision. Other prospective randomized studies have concurred on the role of fusion for stenosis associated with degenerative spondylolisthesis.10,11

Complications associated with surgical intervention for lumbar stenosis are more common in cases of increased preoperative morbidities, advancing age, and complex surgical procedures. Two studies have demonstrated a relationship between mortality rate and age. One study showed a higher mortality rate of 0.6% in patients older than 75 years (about ninefold compared with patients younger than 75 years) with a complication rate of 17.7% (compared with 9.1%).12 The second study showed similarly increased rates for patients older than 80 years.13 The most commonly cited comorbidities in the literature are osteoarthritis, cardiac disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and chronic pulmonary disease. However, the risk factors most closely correlated with a poor outcome are preoperative complaints of predominantly low back pain, followed by preoperative comorbidities. Complications of decompression procedures are postoperative neurologic deficit, dural tear, cerebrospinal fluid fistulas and pseudomeningoceles, facet fractures, infection, and vascular injury.

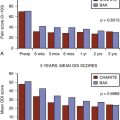

Weinstein and colleagues14 examined 1244 patients in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) and divided patients into prospective randomized (501 participants) and observational (743 participants) cohorts at 13 spine clinics in 11 U.S. states. Patients were observed at 4 years using SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) and Physical Function (PF) scales and the modified Oswestry Disability Index (ODI, AAOS/Modems version) assessed at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and annually thereafter. In the 4-year combined as-treated analysis, those receiving surgery demonstrated significantly greater improvement in all the primary outcome measures (mean change surgery versus nonoperative; treatment effect): BP (45.6 vs. 30.7; 15.0; 11.8 to 18.1), PF (44.6 vs. 29.7; 14.9;12.0 to 17.8) and ODI (−38.1 vs. −24.9; −13.2; −15.6 to −10.9). The percentage of patients working was similar between the surgery and nonoperative groups, 84.4% versus 78.4%, respectively.

Spinal Stenosis with Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

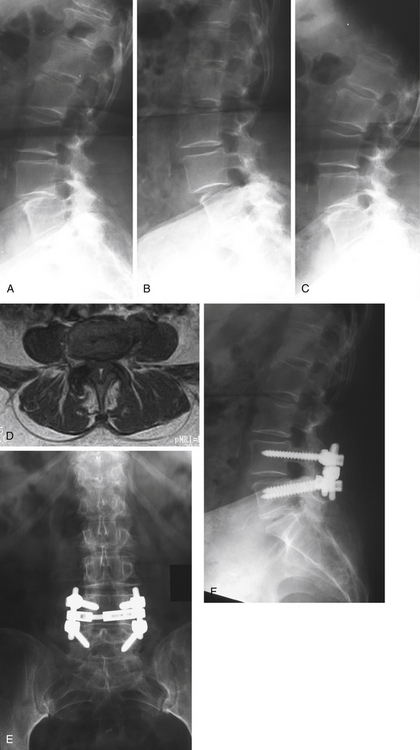

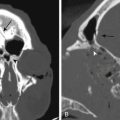

Degenerative spondylolisthesis is described as the anterior translation of one vertebral body over another adjacent vertebra in the absence of a defect of the pars interarticularis. The listhesis can cause lower back pain, radicular pain, and/or symptoms of neurogenic claudication (Fig. 165-2).

The main goal of treatment in spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis is decompression of both the exiting and traversing nerve root. The role of arthrodesis, with or without instrumentation, in the treatment of spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis is controversial. In a retrospective review of 290 patients who underwent decompression laminectomy with 10-year follow-up, the reported outcome was excellent in 69%, good in 13%, fair in 12%, and poor in 6%. Reoperation rate for pseudarthrosis was only 2.7%.15 A prospective randomized study conducted by Herkowitz and Kurz compared the results at 3 years’ follow-up of decompression alone versus decompression and intertransverse arthrodesis in patients with one level of spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis.10 Only 44% of patients with decompression without fusion reported a satisfactory outcome compared with 96% of patients reporting the same outcome who received decompression plus fusion. Patients who underwent concomitant arthrodesis had significantly better results. Moreover, despite the pseudarthrosis rate of 36% in patients who underwent decompression and in situ fusion, all had good to excellent results. The slip did not significantly progress in either group. The investigators concluded that patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis and stenosis should undergo concomitant arthrodesis at the time of decompression.

An attempted meta-analysis of the literature on degenerative spondylolisthesis was performed by Mardjetko and colleagues.16 This analysis demonstrated that patient outcome was significantly better when concomitant arthrodesis was performed (p < 0.0001). A satisfactory clinical result was found in 69% of the 260 patients who received decompression without spinal arthrodesis; progression of the spondylolisthesis occurred in 31% of these patients. Ninety percent of those who had a surgical decompression with posterolateral arthrodesis achieved a satisfactory clinical outcome, with progressive listhesis in only 17%.

An instrumented arthrodesis has been shown to produce higher fusion rates; however, the clinical outcome of decompression with instrumented spinal fusion for this entity is not completely known.17 Although a pseudarthrosis occurred in 36% of those with an in situ arthrodesis in that investigation, in the study of Herkowitz and colleagues,10 the clinical results ranged from excellent to good in all patients. The investigators concluded that at a mean follow-up of 3 years, a radiographic finding of pseudarthrosis did not preclude a successful result. Fischgrund and colleagues examined 67 patients undergoing decompression and arthrodesis with or without instrumentation.18 Patients undergoing the instrumented arthrodesis demonstrated an 87% fusion rate, whereas patients undergoing a noninstrumented arthrodesis had a 45% fusion rate. However, the higher fusion rate of the instrumented group did not improve their clinical outcome. A landmark follow-up study of longer duration by Kornblum and colleagues reviewed 47 of the original patients who had single-level symptomatic spinal stenosis and spondylolisthesis and who were treated by decompression and in situ arthrodesis.11 These patients were observed over 5 to 14 years, with an average follow-up of 7 years and 8 months. They found that long-term clinical outcome was excellent or good in 86% of patients with solid arthrodesis, but only 56% of those patients who developed a pseudarthrosis. Significant differences in residual back and lower limb pain was discovered between the two groups, with the solid fusion group performing significantly better in the symptom, severity, and physical function categories on self-administered questionnaires. Patients who achieved a solid fusion had improved clinical results, which demonstrated the benefit of a successful arthrodesis over pseudoarthrosis with respect to back and lower limb symptomatology compared with their prior short-term studies. Reviewing the current literature, one may conclude that in the short term, patients who at least have an arthrodesis attempted, even if it results in pseudarthrosis, do better than patients who have no attempt at arthrodesis. Although this “fibrous union” can benefit patients in the short term, long-term results deteriorate in patients who do not have a solid fusion. Based on the literature, one can conclude that patients who receive instrumentation at the same time as arthrodesis have a higher fusion rate.

Weinstein19 and colleagues examined 607 patients in the SPORT trial with degenerative spondylolisthesis. A decompressive laminectomy was the standard surgical protocol. If warranted, a single level fusion was also performed. Of the 607 patients enrolled in the study, 395 patients had surgery within 4 years; 345 of these patients (87%) had surgery during the first year. About one third of patients (212 patients) elected nonsurgical treatment. In the combined analysis, the treatment effects were significantly in favor of surgery for all primary and secondary outcome measures at each time point out to 4 years. Surgery was more effective in resolving neurogenic claudication than nonsurgical treatment. Approximately 85% of the patients had neurogenic claudication, and 15% had radicular symptoms with evidence of nerve root irritation. Patients with radicular symptoms had surgical outcomes similar to those of patients with neurogenic claudication. They did experience greater improvement on average with nonsurgical intervention, however. As a result, patients with radicular symptoms had a smaller relative benefit from surgery than patients with neurogenic claudication.

Combining a higher fusion rate using instrumentation with the desirable long-term clinical effect of achieving a solid fusion makes the case for using instrumentation in the treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis.10,11,16,17,20,21 Fusion performed with instruments improves the likelihood of a solid fusion, which suggests that an instrumented arthrodesis in the treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis is preferred over noninstrumented fusion.

Case Illustrations and Operative Procedures

Case 1

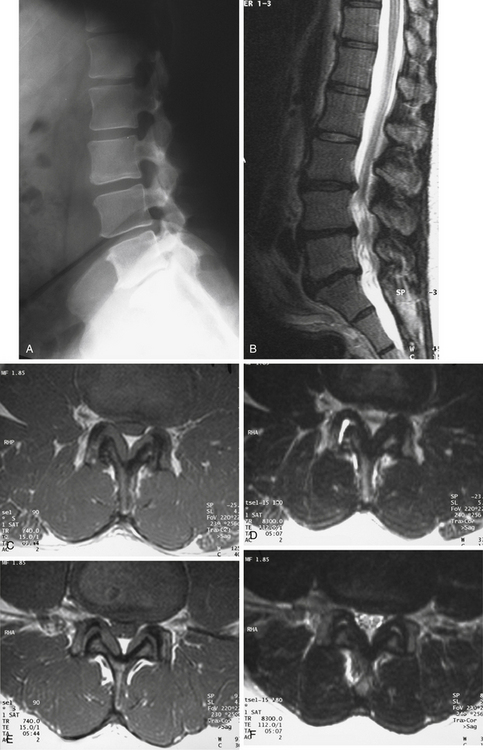

Figure 165-1 illustrates the case of a 54-year-old man presenting with bilateral neurogenic claudication. The initial standing lateral lumbar radiograph (Fig. 165-1A) did not show any evidence of spondylolisthesis. Examinations were completed by a lumbar MRI, showing on the sagittal T2-weighted view (Fig. 165-1B) evidence of L3–L5 degenerative stenosis. Central and lateral recess stenoses were confirmed on the T1 and T2 axial views on both L3–L4 (Fig. 165-1C and D) and L4-L5 (Fig. 165-1E and F). The patient was successfully treated surgically by posterior L3–4 and L4–5 laminectomies.

Case 2

A 71-year-old woman presented with a history of low back pain and bilateral neurogenic claudication (Fig. 165-2). Initial standing lateral lumbar radiograph (Fig. 165-2A) showed evidence of an L4–L5 degenerative spondylolisthesis. Dynamic lateral radiographs were prescribed and demonstrated lumbar instability. The lateral flexion radiograph (Fig. 165-2B) demonstrated increased anterior translation relative to that shown in the neutral radiograph, and the lateral extension radiograph (Fig. 165-2C) showed reduction of the anterior translation. Examinations were completed by a lumbar MRI, and axial imaging scan at L4–L5 (Fig. 165-2D) indicated central and lateral recess stenosis. The patient was successfully treated surgically by a posterior L4–L5 laminectomy associated to pedicle screw fixation plus posterolateral bone grafting using autogenous iliac crest graft. Anteroposterior (Fig. 165-2E) and lateral (Fig. 165-2F) images at 2-year follow-up show satisfactory reduction of the spondylolisthesis and posterior fusion.

Operative Procedure

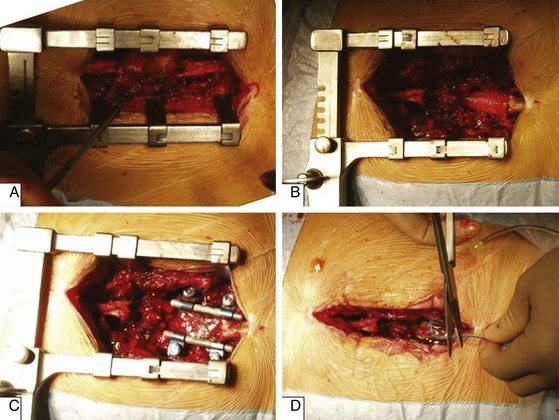

A common posterior operative procedure for lumbar degenerative disorders is shown in Figure 165-3. After spinal exposure, resection of posterior elements is started by removal of the spinous process (Fig. 165-3A), then laminectomy is performed to provide space for thecal sac and nerve roots (Fig. 165-3B). In a case of instability, spinal fusion can be performed (Fig. 165-3C) using pedicle screw fixation and bone grafting; this step is optional for stenosis. The wound is usually closed with drainage (Fig. 165-3D).

Atlas S.J., Deyo R.A., Keller R.B., et al. The Maine Lumbar Spine Study, Part III. 1-year outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1996;21(15):1787-1794.

Deyo R.A., Cherkin D.C., Loeser J.D., et al. Morbidity and mortality in association with operations on the lumbar spine. The influence of age, diagnosis, and procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(4):536-543.

Deyo R.A., Ciol M.A., Cherkin D.C., et al. Lumbar spinal fusion. A cohort study of complications, reoperations, and resource use in the Medicare population. Spine. 1993;18(11):1463-1470.

Epstein N.E. Decompression in the surgical management of degenerative spondylolisthesis: advantages of a conservative approach in 290 patients. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11(2):116-122.

Fischgrund J.S., Mackay M., Herkowitz H.N., et al. 1997 Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective randomized study comparing decompressive laminectomy and arthrodesis with and without spinal instrumentation. Spine. 1997;22:2807-2812.

Gibson J.N., Grant I.C., Waddell G. The Cochrane review of surgery for lumbar disc prolapse and degenerative lumbar spondylosis. Spine. 1999;24:1820-1832.

Grob D., Humke T., Dvorak J. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Decompression with and without arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):1036-1041.

Herkowitz H.N., Kurz L.T. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. A prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:802-807.

Herron L.D., Mangelsdorf C. Lumbar spinal stenosis. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:26-33.

Jonsson B., Annertz M., Sjoberg C., et al. A prospective and consecutive study of surgically treated lumbar spinal stenosis. Part II. Five year follow-up by an independent observer. Spine. 1997;22:2938-2944.

Katz J.N., Lipson S.J., Larson M.G., et al. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:809-813.

Kornblum M.B., Fischgrund J.S., Herkowitz H.N., et al. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective long-term study comparing fusion and pseudarthrosis. Spine. 2004;29(7):726-733.

Mardjetko S.M., Connolly P.J., Shott S. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. A meta-analysis of literature 1970–1993. Spine. 1994;19(Suppl):2257-2265.

Matsui H., Tsuji H., Sekido H., et al. Results of expansive laminoplasty for lumbar spinal stenosis in active manual workers. Spine. 1992;17(Suppl):37-40.

Postacchini F., Cinotti G., Perugia D., et al. The surgical treatment of central lumbar stenosis. Multiple laminotomy compared with total laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:386-392.

Thomsen K., Christensen F.B., Eiskjaer S.P., et al. 1997 Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. The effect of pedicle screw instrumentation on functional outcome and fusion rates in posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Spine. 1997;22(24):2813-2822.

Turner J.A., Ersek M., Herron L., et al. Surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: Attempted meta-analysis of the literature. Spine. 1992;17:1-8.

Weinstein J.N., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1295-1304.

Weinstein J.N., Tosteson T.D., Lurie J.D., et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis four-year results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial. Spine. 2010;35:1329-1338.

Wiltse L.L., Newman P.H., Macnab I. Classification of spondylolisis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:23-29.

Zdeblick T.A. A prospective, randomized study of lumbar fusion. Preliminary results. Spine. 1993;18(8):983-991.

1. Wiltse L.L., Newman P.H., Macnab I. Classification of spondylolisis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:23-29.

2. Postacchini F., Cinotti G., Perugia D., et al. The surgical treatment of central lumbar stenosis. Multiple laminotomy compared with total laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:386-392.

3. Matsui H., Tsuji H., Sekido H., et al. Results of expansive laminoplasty for lumbar spinal stenosis in active manual workers. Spine. 1992;17(Suppl):37-40.

4. Atlas S.J., Deyo R.A., Keller R.B., et al. The Maine Lumbar Spine Study, Part III. 1-year outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1996;21(15):1787-1794.

5. Jonsson B., Annertz M., Sjoberg C., et al. A prospective and consecutive study of surgically treated lumbar spinal stenosis. Part II. Five year follow-up by an independent observer. Spine. 1997;22:2938-2944.

6. Herron L.D., Mangelsdorf C. Lumbar spinal stenosis. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:26-33.

7. Katz J.N., Lipson S.J., Larson M.G., et al. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:809-813.

8. Turner J.A., Ersek M., Herron L., et al. Surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: attempted meta-analysis of the literature. Spine. 1992;17:1-8.

9. Grob D., Humke T., Dvorak J. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Decompression with and without arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):1036-1041.

10. Herkowitz H.N., Kurz L.T. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. A prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:802-807.

11. Kornblum M.B., Fischgrund J.S., Herkowitz H.N., et al. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective long-term study comparing fusion and pseudarthrosis. Spine. 2004;29(7):726-733.

12. Deyo R.A., Cherkin D.C., Loeser J.D., et al. Morbidity and mortality in association with operations on the lumbar spine. The influence of age, diagnosis, and procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(4):536-543.

13. Deyo R.A., Ciol M.A., Cherkin D.C., et al. Lumbar spinal fusion. A cohort study of complications, reoperations, and resource use in the Medicare population. Spine. 1993;18(11):1463-1470.

14. Weinstein J.N., Tosteson T.D., Lurie J.D., et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis four-year results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial. Spine. 2010;35:1329-1338.

15. Epstein N.E. Decompression in the surgical management of degenerative spondylolisthesis: advantages of a conservative approach in 290 patients. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11(2):116-122.

16. Mardjetko S.M., Connolly P.J., Shott S. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. A meta-analysis of literature 1970–1993. Spine. 1994;19(Suppl):2257-2265.

17. Gibson J.N., Grant I.C., Waddell G. The Cochrane review of surgery for lumbar disc prolapse and degenerative lumbar spondylosis. Spine. 1999;24:1820-1832.

18. Fischgrund J.S., Mackay M., Herkowitz H.N., et al. 1997 Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective randomized study comparing decompressive laminectomy and arthrodesis with and without spinal instrumentation. Spine. 1997;22:2807-2812.

19. Weinstein J.N., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1295-1304.

20. Thomsen K., Christensen F.B., Eiskjaer S.P., et al. 1997 Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. The effect of pedicle screw instrumentation on functional outcome and fusion rates in posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Spine. 1997;22(24):2813-2822.

21. Zdeblick T.A. A prospective, randomized study of lumbar fusion. Preliminary results. Spine. 1993;18(8):983-991.