3 Management and policies

Purpose of the PACU

The effects on staffing and the use of PACU beds for a multitude of services—such as cardiac catheterization, arteriography or specialized radiologic tests, electroshock therapy, other special procedures, or observation of patients who have undergone special procedures—have created special concerns in the management of the PACU. Another recent development is the use of the PACU for patients of the intensive care unit, telemetry, or emergency departments when no beds are available in those areas of the hospital. A shortage of hospital medical and surgical beds has also turned the PACU into a holding area for surgical patients awaiting inpatient bed availability. Specific policies and procedures that address any special procedures performed in the PACU and nursing care of these nonsurgical and post-PACU patients need to be developed and in place before these situations arise. A list of potential PACU policy and procedure titles can be found in Box 3-1.

BOX 3-1 Suggested Policies and Procedures for the PACU

• Purpose and structure of the unit

• Quality management and performance improvement

Adapted from Shick L, Windle PE: ASPAN’s perianesthesia core curriculum: preprocedure, phase I and phase II PACU nursing, ed 2, St. Louis, 2010, Saunders.

Organizational structure

Patient classification

Most PACUs have some type of patient classification system (PCS) either formal or informal. The most accurate PCSs are those that base the patient classification on length of stay in the PACU and intensity of the care required. The PCS can be used to justify budget for staffing and supplies as well as space requirements and charges for the PACU stay. For example, a patient with a classification of 1 has a lower charge than a patient with a classification of 3.

Visitors

The merits and benefits of visitation in the PACU are well documented. Patient visitation lowers anxiety and decreases stress for both the patient and the family. The result is an increase in patient and family satisfaction and increased adherence to the recovery plan.1,2 In the past, PACU visitation was restricted for reasons such as the lack of privacy, the acuity of the patients, and the fast turnover that is common to the PACU. Visitation may have been allowed only if staffing and the physical structure of the unit permitted. In many institutions a change in culture surrounding PACU visitation has shown that the positive outcomes from visitation have outweighed the real and perceived drawbacks. A main catalyst behind the change has been the lack of available postoperative beds, thus extending the stay in the PACU for many patients. Some patients may have a prolonged stay in the PACU while they await critical care, telemetry, or surgical beds in the nursing unit. As the frequency of morning admissions increases, the incidence rate of extended PACU stays also increases because of lack of postoperative bed availability.1,3

Part of the challenge with a change in the organizational culture to allow visitation in the PACU is that nursing care historically has concentrated on the care of the patient only. However, many family members also need nursing interventions, such as explanations of the PACU care provided to their loved ones, and require time and effort on the part of the nurses. However, PACU visitation can provide an excellent opportunity to start postoperative education with families.

Situations in which visitation should be encouraged include the following:

• Death of the patient may be imminent.

• The patient must return to surgery.

• The patient is a child whose physical and emotional well being may depend on the calming effect of the parent’s presence.

• The patient’s well being depends on the presence of a significant other. Patients in this category include persons with mental disabilities, mental illnesses, or profound sensory deficits.

• The patient needs a translator because of language differences.

Discharge of the patient from the PACU

• The patient regained consciousness and is oriented to time and place (or return to baseline cognitive function).

• The patient’s airway is clear and danger of vomiting and aspiration passed.

• The patient’s circulatory and respiratory vital signs are stabilized.

The use of a numeric scoring system for assessment of the patient’s recovery from anesthesia is common. Many institutions have incorporated the postanesthesia recovery score as part of the discharge criteria. Box 3-2 shows an example of two discharge scoring systems. The Aldrete Scoring System was introduced by Aldrete and Kroulik in 1970 and was later modified by Dr. Aldrete to reflect oxygen saturation instead of color. Clinical assessment must also be used in the determination of a patient’s readiness for discharge from the PACU. This scoring system does not include detailed observations such as urinary output, bleeding or other drainage, changing requirements for hemodynamic support, temperature trends, or patient’s pain management needs. All these criteria should be considered in the determination of readiness for discharge. The unit policy and the established PACU discharge criteria determine the appropriate postanesthesia recovery score and physical condition for discharge from the PACU. The patient must have a preestablished score to be discharged from the PACU. Scores or conditions lower than the preestablished level necessitate evaluation by the anesthesia provider or surgeon and can result in an extension of the PACU stay or possible disposition to a special care or critical care unit.

BOX 3-2 Discharge Scoring Systems

From Ead H: From Aldrete to PADSS: reviewing discharge criteria after ambulatory surgery, J Perianesth Nurs 21(4): 259–267, 2006.

When ambulatory surgical patients are discharged to home, other criteria should be assessed. These criteria may include the following: pain control to an acceptable level for the patient, control of nausea, ambulation in a manner consistent with the procedure and previous ability, and a responsible adult present to accompany the patient home. Some Phase II PACUs require the patient to void or tolerate oral fluids before discharge to home. The Post Anesthetic Discharge Scoring System is often used for assessing the readiness of the patient to be discharged home or to an extended observation area.4

Standards of care

Every profession has the responsibility to identify and define its practice to protect consumers by ensuring the delivery of quality service.1 The American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN) Perianesthesia Nursing Standards and Practice Recommendations provides a basic framework for nurses who practice in all phases of the perianesthesia care specialty.1 These standards have been devised to stand alone or be used in conjunction with other health care standards and are monitored, reviewed, revised, and updated regularly. A copy of these standards can be obtained from the ASPAN National Office, 90 Frontage Road, Cherry Hill, NJ 08034-1424, or ordered via the ASPAN website at www.aspan.org.

Quality management and performance improvement

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initiated the Surgical Care Improvement Project. This project is a multiple-year national campaign and partnership of leading public and private healthcare organizations aimed at reducing surgical complications. PACU staff members have a major role in partnering with both the surgeon and anesthesia providers to ensure that many of these measures are addressed appropriately.5 Every nurse is responsible for quality management and performance improvement. The result is an effective program that has a positive effect on the process and outcome of care where patient care problems can be prevented, or where basic operating procedures or systems can be changed and improved.

Collaborative management

The PACU setting is a multifaceted, complex area. It encompasses the PACU staff and requires close working relations with the entire perioperative team to ensure the safest care and best outcome for the patient. The anesthesia providers have a key role in the functioning of the PACU. The partnerships between PACU and the anesthesia staff members must be strong because it is the anesthesia provider who is the first line of defense for addressing patient issues in the PACU. In addition to anesthesia providers, the PACU and operating room staff, along with the surgeon and their team, must work in tandem to provide safe care. All who work in the PACU need to exhibit excellent communication skills, mutual respect, and the ability to collaborate effectively with different personalities and people of different cultures.

Role delineation

Clinical nurse specialist

Qualifications of the CNS include strong leadership skills, clinical expertise in the perianesthesia setting, excellent communication skills, the ability to share knowledge and ensure understanding, the ability to work in a collaborative manner with all members of the health care team, the capability to incorporate nursing research into practice, and the ability to multitask. The CNS usually is a master’s-prepared nurse or may be doctorally prepared (e.g., doctorate of nursing practice [DNP]). The nurse in this role should possess advanced clinical expertise in perianesthesia nursing. The CNS should also have CPAN or CAPA certification. Each institution develops role requirements for the CNS. Examples of activities that may involve the CNS are included in Box 3-3.

BOX 3-3 Examples of CNS Activities

• Education of PACU clinical staff (RNs, LPNs, UAPs)

• Education of hospital and facility staff who receive patients from the PACU

• Development and implementation of new programs and services

• Development and implementation of patient and family education programs

• Quality improvement activities

• Liaison between management and staff nurses

• Liaison between departments (e.g., anesthesia, operating room, surgical units, critical care units)

• Evaluation of clinical staff members outside the PACU (e.g., surgical units, critical care units)

The CNS works closely with the nurse manager to achieve the mission and goals of the PACU. In addition, the CNS is involved in ensuring the clinical competencies of each perianesthesia nurse and provides in-service training and education to the staff on health care regulatory requirements and standards.

Staff nurses

The following qualifications should be considered in establishing selection criteria. The nurse who considers employment in the PACU must have an interest in perianesthesia nursing. The nurse needs a solid foundation in the care required for preanesthesia and postanesthesia patients1 and should be committed to providing high-quality, individualized patient care. The candidate should also demonstrate exceptional communications skills and communicate in a positive manner with all members of the health care team. The nurse should have the ability to form good working relationships and be a positive team player. The perianesthesia nurse should be capable of making intelligent independent decisions and initiating appropriate action as necessary, and willing to accept the responsibility that accompanies working in a critical care unit. In addition, the nurse must have excellent patient teaching skills, the ability to coordinate care being rendered by a variety of health care team members, and the ability to function effectively in a crisis situation. The ability to be flexible is of the utmost importance for nurses working in the PACU.

The cross-training of nurses to the PACU may be a feasible solution in hospitals or facilities where staffing is a concern. The nurse who is cross-trained to the PACU should fulfill the required competencies of competent support staff as outlined in the ASPAN Perianesthesia Nursing Standards and Practice Recommendations.1

Membership in professional organizations as well as national certification by one of the professional nursing associations (Table 3-1) shows commitment to professional excellence and should be considered positively in the selection of perianesthesia nurses. If everything else is equal, ideally, candidates for PACU positions who have attained a CPAN or CAPA credential should be given preference in hiring. Commitments to other professional nursing organizations should also help the candidate to be considered for a PACU position.

Table 3-1 Certification by Professional Nursing Associations

| PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATION | CREDENTIAL |

|---|---|

| American Nurses Association | Medical-surgical certification |

| American Association of Critical Care Nurses | CCRN |

| American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses | CPAN or CAPA |

| Association of peri-Operative Registered Nurses | CNOR |

| Emergency Nurses Association | CEN |

CPAN, Certified Post Anesthesia Nurse; CAPA, Certified Ambulatory Perianesthesia Nurse; CEN, Certified Emergency Nurse; CCRN, Critical Care Registered Nurse; CNOR, a certification of competency in the field of perioperative nursing.

Certification in basic cardiac life support (BCLS) and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) is required of all nurses who work in the PACU.1 For units with a high volume of pediatric patients, certification in pediatric advanced life support (PALS) is also required. Application of BCLS in the PACU or ambulatory surgical unit helps to sustain a patient’s condition in a crisis until ACLS techniques can be instituted. ACLS includes training in dysrhythmia recognition, intravenous infusion, blood gas interpretation, defibrillation, intubation, and emergency drug administration. If the perianesthesia nurse responds quickly and efficiently during crisis situations, the patient’s chance of survival increases.

Ancillary personnel

Minimal numbers of ancillary personnel should be assigned to the unit to support the registered nurses. Licensed practical nurses (LPNs) or licensed vocational nurses (LVNs) assigned to the PACU are restricted in their roles. A registered nurse must be the primary nursing care provider in the PACU, thereby limiting the role of the practical nurse in the PACU setting to one that does not allow functioning at their fullest capacity. This situation often causes dissatisfaction for the LPN/LVN and is not a cost effective use of limited budget dollars. Some PACUs have effectively used the LPN/LVN as a transport nurse to deliver appropriate patients safely to the unit after discharge. The PACU may employ unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP). When working with UAPs, the registered nurse (RN) is responsible for knowing the policies and procedures as set forth by the individual institution. UAPs can be a valuable asset to the PACU, but the RN should remain cognizant of the fact that nursing assessment, diagnosis, outcome identification, planning, implementation and evaluation cannot be delegated to UAPs. UAPs can assist the nurse by performing tasks that the perianesthesia RN supervises and determine the appropriate use of UAP providing direct patient care in accordance with state regulations.1 Ultimately, the RN is responsible and accountable for the safe delivery of nursing care.

Talent recruitment, retention, and review considerations

Retaining nursing staff in the PACU

As demand continues to outweigh supply, the existing nursing shortage only worsens over time. Regrettably, perianesthesia nursing is not immune to this shortage. Many nurses have found the perianesthesia specialty to be where they want to focus their careers. This group of experienced, dedicated staff members is an exceptional bonus to institutions lucky enough to have them. Unfortunately, many of these nurses are from the baby boomer generation and are looking to retire in the near future. At the same time, fewer nurses are graduating and demand for nurses is growing. Simultaneously, many colleges and universities have seen the recent number of nursing applicants increase, only to be turned away because of the lack of qualified nursing educators.6

In order to recruit and retain the dedicated and talented nurses needed in the perianesthesia setting, institutions must look at factors that influence job satisfaction and retainability. Recruitment into nursing and into specific hospitals is a widely discussed topic. After nurses are recruited into the perianesthesia setting, retention of these experienced staff members becomes a major challenge. Although salary is a factor, studies show that it is not the top reason for dissatisfaction and turnover.7 Items such as a workplace environment free from ongoing conflict, where staff has autonomy and where their ideas and opinions are valued, play a big role in job satisfaction. Other issues such as inflexible working hours and mandatory overtime are also major causes of dissatisfaction. Some research has defined that the nurse manager leadership behaviors and relations with staff members had the most influence on retention of hospital staff nurses (Box 3-4).

BOX 3-4 Retention Practices for Nurse Managers

• Use of preceptors for new hires

• High-risk retention monitoring

• Supplies and resources available to do the job

Modified from The Advisory Board Company: Becoming a chief retention officer, Washington, DC, 2001, The Advisory Board Company: Nursing Executive Center.

Retention of qualified nurses is fast becoming a priority for nursing administration. In exit interviews, nurses cite an unhealthy work environment as the reason they leave the workplace. The treatment of nurses toward each other continues to be challenge. Some reasons given for nurses who leave the workplace include lack of support, mentoring, and clear direction.8 Nurses are not exempt from conflict in the workplace. As trite as it may seem, women are generally expected to work harmoniously together in a sisterlike fashion. This belief could not be farther from the truth. When issues of conflict arise, some individuals may find it difficult to confront the situation and establish a resolution. As a result, an ongoing underlying current of tension may exist on the unit. Box 3-5 identifies some strategies that the nurse manager may use to build a supportive workplace.

BOX 3-5 Management Strategies to Build a Supportive Workplace

• Forge honest and open relationships.

• Demonstrate how to deal effectively with colleagues who disagree or disapprove.

• Recognize when being “nice” prevents discussion and resolution of issues.

• Acknowledge conflicts and find solutions.

• Recognize that some competitive tensions will always exist and talk them through.

• Openly discuss how dealing with the issues can lead to optimism, movement, and growth.

• Lead with respect for each person and empathy for the inevitable workplace tensions that will arise.

From Vestal K: Conflict and competition in the workplace, Nurs Leader 4(6):6–7, 2006.

Creation of an environment conducive to staff growth and development is the manager’s responsibility. A survey conducted by the American Academy of Nursing in 1982 identified variables in nursing that attracted and retained quality nurses. These variables include nursing autonomy and personal and job satisfaction, and nursing practice that resulted in excellence. As a result of this survey, the Magnet Recognition Program was established for recognizing health care organizations that provide nursing excellence.9 Facilities that strive for recognition as a Magnet facility have identified that the nurses employed at the facility provide quality patient care. Nurses who believe they have the support and resources needed to provide quality patient care are more likely to be satisfied in the workplace.

Basic staff orientation program

Each nurse who undergoes orientation to the PACU should have an individually assigned preceptor. The preceptor works closely with the CNS and orientee to ensure that individual needs are met and deficiencies are addressed promptly. In addition, anesthesia providers, surgeons, the CNS, and other nurses in the PACU should be involved in the orientation program. Fostering of seasoned nurses to prepare and present short lectures or skill demonstrations not only recognizes the nurse for individual expertise but also displays the manager’s confidence in the individual’s ability to provide quality patient care. Lectures and presentations should be geared toward the specific needs of the orientee.

Content of the orientation program

The length of the orientation program should be tailored to meet the individual needs and previous experience of the orientee. Consideration should be given to the expectations placed on the orientee. Will they be expected to perform in a “call” situation at the conclusion of the orientation period, or will an experienced perianesthesia nurse be working with them for an indefinite period? The orientation period should be customized and adjusted as needed based on the orientee’s ability to grasp, understand, and process the information and situations encountered. During the orientation time, the orientee should work full time. An experienced perianesthesia nurse will require a much shorter orientation phase than an inexperienced PACU nurse. Suggested topics and content of the PACU orientation program are presented in Box 3-6. Additional material, as appropriate to the practice setting, should also be included.

BOX 3-6 Suggested Topics for a PACU Orientation Program

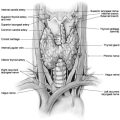

Review of the anatomy and physiology of the cardiorespiratory system

• Pathophysiologic processes of the cardiorespiratory system

• Factors that alter circulatory or respiratory function after surgery and anesthesia

• Blood loss and replacement; intake and output

• Identification and treatment

• Airway maintenance, equipment, and techniques, pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic

• Ventilatory support, equipment, and procedures

• Cardiorespiratory arrest and its management

• Treatment of hypotension or hypertension

Care of the patient in the PACU

• Consent (surgical and anesthesia)

• Correct site policy (facility specific)

• Intravenous therapy and blood transfusion

• General comfort and safety measures

From American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses: Perianesthesia nursing standards and practice recommendations 2010–2012, Cherry Hill, NJ, 2010, ASPAN.

During the orientation period, careful and constant communication must be maintained between the nurse manager, the orientee, the preceptor, and the CNS. Evaluation by the nurse manager and preceptor should be ongoing, and the orientee should receive a formal written evaluation at the end of the orientation. The orientee should clearly understand the expectations as set forth by the perianesthesia nurse manager, and the orientee and preceptor should discuss progress daily. If issues arise, the manager or the CNS may need to step in and clearly review progress and expectations with the orientee. In some cases, an orientee might clearly not fit into the perianesthesia environment. In these circumstances, the best solution is to assist the orientee in gaining the required prerequisite skills or explore employment opportunities in another area rather than allowing the orientee to flounder in an environment in which success is not possible.

Development of expertise

Expertise in nursing involves the overlapping of the following three basic components of nursing: knowledge, skill, and experience. Mastering any one or two of these components never equates with expertise. The expert nurse uses a complex linkage of knowledge, experience, skill, clue identification, gut feelings, logic, and intuition in problem-solving and the nursing process. As the nurse gains knowledge and experience through formal and informal programs, nursing intuition begins to develop. Intuition may be thought of as identification of a deviation from the expected or the feeling that “something just doesn’t seem right.” Over time, with experience and practice, the nurse becomes proficient. The accumulation of knowledge, along with the chance to practice the skills acquired, leads to competence.10

Competency assessment

• Unit-specific administrative policies and procedures

• Patient confidentiality and patient rights

• Fire safety and patient safety issues, including The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals11

• Thermoregulation, including normothermia1 and hyperthermia

• Variance and occurrence reporting

• Medications commonly administered in the practice setting, including intravenous moderate sedation, anesthetic agents, antiemetics, and analgesics

• Age-specific competencies (pediatric, adolescent, adult, geriatric)

A complete list of Recommended Competencies for the Perianesthesia Nurse can be found in the ASPAN Perianesthesia Nursing Standards and Practice Recommendations.1

• Monitors, including electrocardiography, pulse oximetry, capnography, and noninvasive blood pressure

• Defibrillator (defibrillation, cardioversion, external pacing)

Managers should develop processes to assess the previously named activities. For assessment of equipment competence, employees must be able to appropriately demonstrate proper use of the specific piece of equipment. Unit-specific tests can be developed to assess competence of policies and procedures.

Staffing

Assignment of nursing personnel to the PACU should be permanent, and staff members should not be routinely rotated to other units. Staffing in the PACU is dependent on volume, patient acuity, patient flow processes, and the physical layout of the unit. Two registered nurses, one of whom is competent in perianesthesia nursing, should be in attendance at all times when a patient is receiving care. ASPAN provides detailed information concerning staffing requirements for phase I, phase II, and extended observation.1

Summary

All management procedures, clinical practices, and policies of the PACU should be established through joint efforts of the PACU staff, the nurse manager, CNS, and the medical director of the unit. These procedures and policies should be written and readily available to all staff members working in the PACU and all physicians using the area for care of patients. Changes in the clinical situation of the facility and advances in science and technology make revision of policies and procedures a continuous challenge.

1. American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses: Perianesthesia nursing standards and practice recommendations. Cherry Hill, NJ: ASPAN; 2010:2010–2012.

2. Dewitt L, Albert N. Preferences for visitation in the PACU. J Perianesth Nurs. 2010;25(5):296–301.

3. Price C, et al. Reducing boarding in a post-anesthesia care unit. Production and Operations Management. 2011;20(3):431–441.

4. Chung F, et al. A post-anesthetic discharge scoring system for home readiness after ambulatory surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7(6):500–506.

5. Anesthesia Business Consultants: Using post-anesthesia data to improve and demonstrate value. available at: www.anesthesiallc.com/about-abc/ealerts/194-using-post-anesthesia-data-to-improve-and-demonstrate-value, 2011. Accessed April 5

6. American Association of Colleges of Nursing: Nursing shortage fact sheet. available at: www.centerfornursing.org/nursemanpower/NursingShortageFactSheet.pdf, April 10, 2011. Accessed

7. Simmons B. Does pay level affect job satisfaction. Available at www.bretlsimmons.com/2010-09/does-pay-level-affect-job-satisfaction, April 10, 2011. Accessed

8. The College Network Blog: Five reasons why new nurses quit. available at: http://blog.collegenetwork.com/blog/the-future-of-distance-education/five-reasons-why-new-nurses-quit, April 15, 2011. Accessed

9. American Nurses Credentialing Center: ANCC magnet recognition program. available at: http://nursingworld.org/ancc/magnet/index.html, April 15, 2011. Accessed

10. Dracup K, Bryan-Brown C. From novice to expert to mentor: shaping the future. Am J Crit Care.2004;13(6):448–450.

11. The Joint Commission: National patient safety goals. available at: www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/npsgs.aspx, April 15, 2011. Accessed