111 Male Genitourinary Emergencies

• The five major male genitourinary emergencies are testicular torsion, Fournier gangrene (necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum), priapism, paraphimosis, and genitourinary tract trauma. An associated emergent condition is an incarcerated or strangulated inguinal hernia.

• Ultrasound examination is the primary diagnostic tool for differentiation of causes of acute scrotal pain.

• Urology services should be consulted immediately after initial patient evaluation when testicular torsion is suspected.

• Pain out of proportion to the findings on physical examination is the hallmark of early Fournier gangrene.

• In the setting of severe scrotal pain, a necrotic or ischemic cause should be suspected. Testicular torsion, Fournier gangrene, and an incarcerated or strangulated inguinal hernia are surgical emergencies.

• A trial of oral terbutaline, a β-adrenergic agonist, is the least invasive initial treatment of priapism. Corporal blood aspiration with or without irrigation or injection of an α-adrenergic receptor agonist (e.g., phenylephrine) may be necessary if the condition is not reversed rapidly.

• Successful reduction of paraphimosis can often be performed at the bedside without specialty consultation.

• A urologist should be engaged in the care of all but the most minor cases of genitourinary trauma.

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

Priapism is a pathologic condition defined as the presence of a persistent erection lasting longer than 4 hours in the absence of sexual desire or stimulation. It most frequently results from engorgement of the corpora cavernosa with stagnant blood (termed low-flow priapism). Box 111.1 lists several causes of low-flow priapism.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Acute Scrotal Pain

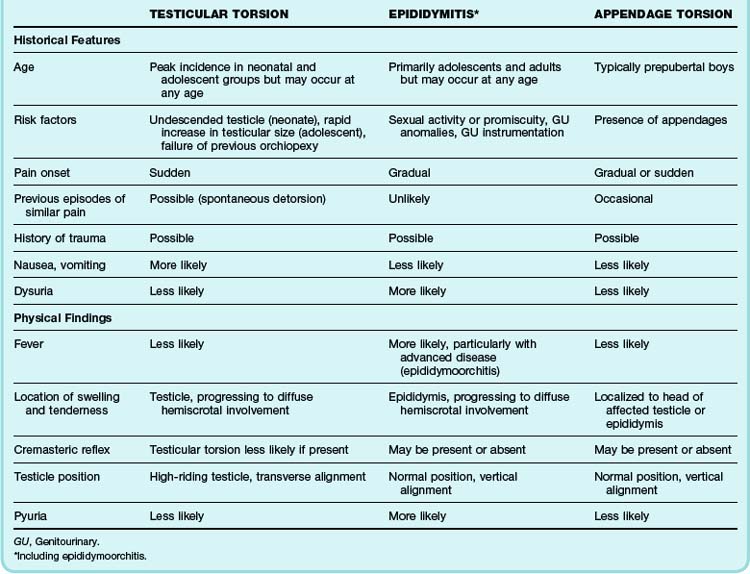

One of the most challenging aspects of male genitourinary complaints is that a wide variety of clinical conditions may all be manifested as acute, unilateral (or bilateral) pain and swelling of the scrotum. Although the differential diagnosis for such symptoms is extensive, threats to life and fertility need to be excluded. Testicular torsion, Fournier gangrene, and an incarcerated or strangulated inguinal hernia are surgical emergencies. The vast majority of acute testicular pain, however, can be attributed to one of three diagnostic entities: testicular torsion, epididymitis, or appendage torsion (Table 111.1).1

Onset of Symptoms

Pain that begins abruptly and is severe suggests testicular torsion.2 Intermittent severe pain can signal intermittent torsion. Twisting of the spermatic cord leads to rapid diminution of blood supply to the affected testicle and resultant ischemic pain. This is in contrast to the more indolent pain of epididymitis, a gradually progressive inflammatory process. Patients with long-standing inguinal hernias often complain of isolated genital pain of prolonged duration. However, patients with an incarcerated (cannot be reduced) or strangulated hernia (with ischemic or infarcted, herniated bowel) may experience more acute pain.

Testicular torsion may accompany a report of minor scrotal trauma.3 Testicular torsion can also take place in the absence of such events and may even occur during sleep.

Associated Symptoms

Patients with nausea or emesis are less likely to have torsion of an appendage or simple, uncomplicated epididymitis. It is more likely that substantial pathology is present. Patients with abdominal pain, nausea, or constitutional symptoms may have testicular torsion, an incarcerated hernia, or another process.2,4,5 Patients with epididymitis may have a low-grade fever, nausea, and malaise; those with advanced infection (e.g., epididymoorchitis) may demonstrate more pronounced constitutional symptoms.6

Physical Examination

Genital Examination

Visual examination of the genitals may reveal cutaneous rashes or lesions, abnormal testicular symmetry or position, edema evident by loss of the scrotal skin folds, and masses. Key visual features of testicular torsion include a high-riding and transverse lie of the affected testicle.2,4,7

Acute Penile Pain

Patients with low-flow priapism often complain of an exquisitely painful and prolonged erection. Stagnant, oxygen-poor, acidic blood accumulates in the corpora and results in ischemic pain. Ischemia may lead to irreversible cellular damage, permanent fibrosis, and impotence if the duration of the pathologic erection is prolonged. Of note, the use of oral erectile dysfunction treatments such as sildenafil (Viagra) have only rarely been associated with priapism.8 Patients with high-flow priapism often complain of a persistent, yet painless erection that is caused by continuous inflow of well-oxygenated blood through traumatic arterial-cavernosal fistulas.

Penile constriction analogous to paraphimosis can also occur. Objects constricting the penile shaft lead to the same pathophysiologic derangements seen with paraphimosis. These objects may be placed intentionally (e.g., string, metal, rubber rings), or the constriction may occur sporadically, as in the case of a hair tourniquet in infants. Hair tourniquets may be very difficult to diagnose because the offending hair is nearly invisible within an edematous coronal sulcus. An occult hair tourniquet should be considered along with testicular torsion in a male infant with inconsolable crying. Removal of the offending hair from the coronal sulcus can be difficult. It has been reported that over-the-counter hair removal products, including depilatories such as Nair, have been used successfully for the removal of digital (finger, toe) hair tourniquets, thus suggesting its utility for penile hair tourniquets as well.9

Genitourinary Trauma

All but the most superficial penetrating scrotal injuries require specialty consultation for possible exploration.10

Penetrating penile injuries require specialty consultation in virtually all cases.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Among the many infections that can cause genital ulceration, genital herpes, syphilis, and chancroid are the most common in the United States; genital herpes is the most prevalent.11

Diagnosis of any of these ulcerative infections is frequently inaccurate when based on the history and physical examination alone.11 Therefore, evaluation of all patients with genital ulcers should include a serologic test for syphilis and a diagnostic evaluation for genital herpes. Testing for H. ducreyi should be performed in settings where chancroid is prevalent.

Special Signs and Techniques

An intact ipsilateral cremasteric reflex is frequently used, though imperfect, for excluding the diagnosis of testicular torsion.12–14 This reflex is elicited by stroking the ipsilateral inner aspect of the thigh, which results in a reflexive elevation of the testicle through contraction of the cremaster muscle. Absence of this reflex is nonspecific in that healthy individuals may lack the reflex altogether, particularly boys in the first few years of life.15 Of note, there have been several published reports of testicular torsion with an intact cremasteric reflex.16–18

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

In cases of Fournier disease, a delay in recognition and surgical débridement can be life-threatening. Early consultation plus administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics is indicated in all suspected cases. However, prompt surgical débridement remains the definitive treatment.19,20

Laboratory Testing

Any patient encountered in the emergency department (ED) with penile discharge should be assumed to have infectious urethritis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend testing to determine the specific cause.11 Urine polymerase chain reaction testing for N. gonorrhea and Chlamydia infection is available at most institutions. Urine samples to test for urethritis should be collected at the initiation of the urine stream without cleansing of the glans; midstream collection and glans cleansing are necessary for urine culture in patients with suspected cystitis or pyelonephritis. If polymerase chain reaction testing is unavailable, swabs of the lining of the distal 1 to 2 cm of the penile urethra are necessary for testing.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound visualization is the most useful diagnostic modality for the evaluation of genitourinary complaints. Color flow duplex Doppler ultrasound is generally helpful in distinguishing potential causes of acute scrotal pain. The classic finding suggestive of testicular torsion is diminished intratesticular blood flow. In addition, examination of the spermatic cord with high-resolution gray-scale sonography may reveal kinking of the spermatic cord.21 In epididymitis, perfusion is normal or increased because of the effects of inflammatory mediators on local vascular beds.

Ultrasound evaluation of acute scrotal problems has its limitations. Surgical scrotal exploration remains the only definitive diagnostic modality in assessing for testicular torsion. When is the risk low enough to safely send a patient home following “normal” ultrasound findings? Even though some series have found ultrasound to be unreliable, other larger series have reported a negative predictive value approaching 97%.22 However, if ultrasound is nondiagnostic of testicular torsion and the clinical picture is still concerning, emergency surgical consultation is prudent.

Treatment

Manual Testicular Detorsion

In the case of prolonged time until definitive treatment, manual testicular repositioning may be attempted. Because testicular torsion usually occurs in a lateral to medial fashion, detorsion is often accomplished by rotation of the affected testicle from medial to lateral. However, medial to lateral torsion occurs up to a third of the time.23 The end point of the detorsion procedure is relief of pain.

Emergency Surgery for Testicular Torsion

Testicular salvage rates are time dependent; more than 90% of testicles are salvaged if detorsion occurs within 6 hours after the onset of symptoms, whereas the salvage rate is less than 20% when treatment is delayed by more than 24 hours.24 Immediate surgical consultation is important when testicular torsion is likely.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antimicrobial agents are indicated in cases of suspected or proven infection. Early broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is imperative in any patient with suspected Fournier disease. Recommended empiric intravenous antimicrobials include ampicillin-sulbactam plus clindamycin and ciprofloxacin or clindamycin plus an aminoglycoside in individuals with known penicillin hypersensitivity.25 The addition of vancomycin to either regimen for expanded gram-positive coverage is reasonable.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Because timely follow-up counseling and treatment of patients with abnormal test results are impractical in the ED setting, empiric antimicrobial treatment of the probable pathogens should be initiated (Table 111.2), and counseling regarding notification of the patient’s sexual contacts should be underscored. Patients should wear a condom during intercourse following treatment for at least 1 week after the symptoms have resolved, although the CDC recommends consistent use of latex condoms to reduce the risk for many sexually transmitted diseases, including human immunodeficiency virus.26

Table 111.2 Medication Dosages for Sexually Transmitted Diseases

| RECOMMENDED TREATMENT | ALTERNATIVE | |

|---|---|---|

| Ulcerative Disease | ||

| Genital herpes | ||

| Primary | Acyclovir, 400 mg tid × 7-10 days | Valacyclovir, 1 g bid × 7-10 days |

| Recurrent | Acyclovir, 400 mg tid × 5 days | Valacyclovir, 1 g once daily × 5 days |

| Syphilis | Benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units IM × 1 dose | Doxycycline, 100 mg bid × 14 days |

| Chancroid | Azithromycin, 1 g PO × 1 dose | Ceftriaxone, 250 mg IM × 1 dose |

| Urethritis | ||

| Gonorrhea | Ceftriaxone, 250 mg IM × 1 dose | Cefixime, 400 mg PO × 1 dose |

| Chlamydia | Azithromycin, 1 g PO × 1 dose | Doxycycline, 100 PO bid × 7 days |

Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59(RR-12):18-55.

Epididymitis may also occur in prepubescent boys as a result of reflux of sterile urine into the epididymis; it often results from minor congenital genitourinary anomalies that need diagnostic evaluation. Treatment typically includes prophylactic antimicrobials to cover the common urinary pathogens.27

Priapism

A urologist usually manages the treatment of priapism; however, in certain circumstances the emergency physician may have to initiate treatment of low-flow priapism. The classic teaching is that the initial treatment—oral (or subcutaneous) terbutaline—is the same regardless of the inciting etiology, although its utility is debated.28–30 It is thought that terbutaline, a β2-adrenergic agonist, increases venous outflow from the engorged corpora by way of relaxation of venous sinusoidal smooth muscle. Terbutaline is of unproved benefit; however, given its limited propensity for adverse effects, a trial is reasonable in selected circumstances while awaiting urology consultation.31

If terbutaline fails to work rapidly, the next step in the treatment of priapism is corporal blood aspiration with or without irrigation and injection of an α-adrenergic receptor agonist such as dilute phenylephrine. Phenylephrine should be diluted in normal saline to a concentration of 0.1 to 0.5 mg/mL and 1-mL injections made intermittently for upward of 1 hour. Lower concentrations in smaller volumes should be used in children and patients with severe cardiovascular disease.30

Paraphimosis

Paraphimosis can frequently be managed in the ED without the need for emergency specialty consultation. Many methods for successful reduction of paraphimosis have been reported; however, the most commonly used initial maneuver involves manual compression of the distal glans penis to decrease edema, followed by reduction of the glans penis back through the proximal constricting band of foreskin.32

Testicular Trauma

Patients with penetrating injury to the scrotum generally undergo exploration in the operating room. Patients with blunt testicular trauma and ultrasonographic evidence of significant testicular injury also generally undergo surgical exploration for débridement of devitalized tissue, treatment of an acute hematocele larger than 5 cm, or repair of the tunica albuginea.33 Documented testicular injury requires early repair to minimize the potential for infection, infarction, necrosis, abscess, infertility, atrophy, and testicular loss.

Beni-Israel T, Goldman M, Bar Chaim S. Clinical predictors of testicular torsion as seen in the pediatric ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:786–789.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):67–69.

Choe JM. Paraphimosis: current treatment options. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:2623–2626.

Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel. The management of priapism. Baltimore: American Urological Association; 2003. [Reaffirmed September 28, 2009]. Available at http://guidelines.gov/content.aspx?id=3741 Accessed January 29, 2012

Roberts JR, Price C, Mazzeo T. Intracavernous epinephrine: a minimally invasive treatment for priapism in the emergency department. J Emerg Med.. 2009;3:285–289. 36

Van Der Horst C, Martinez Portillo FJ, Seif C, et al. Male genital injury: diagnostics and treatment. BJU Int. 2004;93:927–930.

1 Ben-Chaim J, Leibovitch I, Ramon J, et al. Etiology of acute scrotum at surgical exploration in children, adolescents and adults. Eur Urol. 1992;21:45–47.

2 Ciftci AO, Senocak ME, Tanyel FC, et al. Clinical predictors for differential diagnosis of acute scrotum. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004;14:333–338.

3 Seng YJ, Moissinac K. Trauma induced testicular torsion: a reminder for the unwary. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000;17:381–382.

4 Beni-Israel T, Goldman M, Bar Chaim S. Clinical predictors of testicular torsion as seen in the pediatric ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:786–789.

5 Jefferson RH, Perez LM, Joseph DB. Critical analysis of the clinical presentation of acute scrotum: a 9-year experience at a single institution. J Urol. 1997;158:1198–1200.

6 Likitnukul S, McCracken GH, Jr., Nelson JD, et al. Epididymitis in children and adolescents. A 20-year retrospective study. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141:41–44.

7 Kadish HA, Bolte RG. A retrospective review of pediatric patients with epididymitis, testicular torsion, and torsion of testicular appendages. Pediatrics. 1998;102:73–76.

8 Goldmeier D, Lamba H. Prolonged erections produced by dihydrocodeine and sildenafil. BMJ. 2002;324:1555.

9 Barton DJ, Sloan GM, Nichter LS, et al. Hair-thread tourniquet syndrome. Pediatrics. 1998;82:925–928.

10 Van Der Horst C, Martinez Portillo FJ, Seif C, et al. Male genital injury: diagnostics and treatment. BJU Int. 2004;93:927–930.

11 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):67–69.

12 Rabinowitz R. The importance of the cremasteric reflex in acute scrotal swelling in children. J Urol. 1984;132:89–90.

13 Caldamome AA, Valvo JR, Altebarmakian VK, et al. Acute scrotal swelling in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1984;19:581–584.

14 Melekos MD, Asbach HW, Markou SA. Etiology of acute scrotum in 100 boys with regard to age distribution. J Urol. 1988;139:1023–1025.

15 Caesar RE, Kaplan GW. The incidence of the cremasteric reflex in normal boys. J Urol. 1994;152:779–780.

16 Feldstein MS. Re: the importance of the cremasteric reflex in acute scrotal swelling in children. J Urol. 1985;133:488.

17 Hughes ME, Currier SJ, Della-Giustina D. Normal cremasteric reflex in a case of testicular torsion. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:241–242.

18 Nelson CP, Williams JF, Bloom DA. The cremasteric reflex: a useful but imperfect sign in testicular torsion. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1248–1249.

19 Corman JM, Moody JA, Aronson W. Fournier’s gangrene in a modern surgical setting: improved survival with aggressive management. BJU Int. 1999;84:85–88.

20 Basoglu M, Ozbey I, Selcuk Atamanalp S, et al. Management of Fournier’s gangrene: review of 45 cases. Surg Today. 2007;37:558–563.

21 Kalfa N, Veyrac C, Lopez M, et al. Multicenter assessment of ultrasound of the spermatic cord in children with acute scrotum. J Urol. 2007;177:297–301.

22 Lam WW, Yap T, Jacobsen AS, et al. Colour Doppler ultrasonography replacing surgical exploration for acute scrotum: myth or reality? Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:597–600.

23 Sessions AE, Rabinowitz R, Hulbert WC, et al. Testicular torsion: direction, degree, duration, and disinformation. J Urol. 2003;169:663–665.

24 Visser AJ, Heyns CF. Testicular function after torsion of the spermatic cord. BJU Int. 2003;92:201.

25 Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1373–1406.

26 Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Male latex condoms and sexually transmitted diseases, condom fact sheet in brief. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/brief.html#Consistent Accessed January 24, 2012

27 McAndrew HF, Pemberton R, Kikiros CS, et al. The incidence and investigation of acute scrotal problems in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:435–437.

28 Lowe JC, Jarow JP. Placebo-controlled study of oral terbutaline and pseudoephedrine in management of prostaglandin E1–induced prolonged erections. Urology. 1993;42:51–54.

29 Govier FE, Jonsson E, Kramer-Levin D. Oral terbutaline for the treatment of priapism. J Urol. 1994;151:878–879.

30 Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel. The management of priapism. Baltimore: American Urological Association; 2003. [Reaffirmed September 28, 2009]. Available at http://guidelines.gov/content.aspx?id=3741 Accessed January 24, 2012

31 Priyadarshi S. Oral terbutaline in the management of pharmacologically induced prolonged erection. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16:424–426.

32 Choe JM. Paraphimosis: current treatment options. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:2623–2626.

33 Buckley JC, McAninch JW. Diagnosis and management of testicular ruptures. Urol Clin North Am. 2006;33:111–116.