Chapter 16 Male Genitalia, Hernias, and Rectal Exam

“God gave Man the penis and the brain as His two greatest gifts.

Unfortunately, He made it so that Man could only use one at a time.”

A. Male Genitalia

1 What are the main components of the male reproductive system?

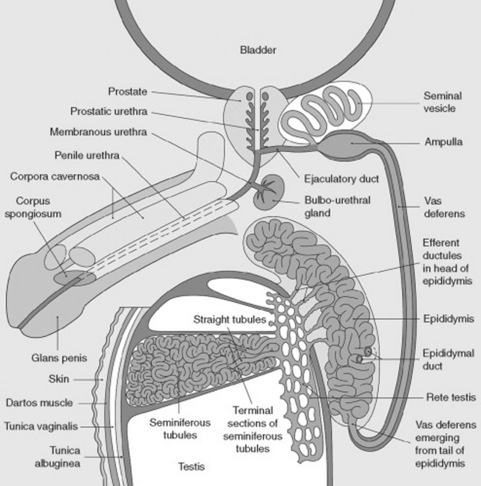

The penis, the scrotum (with testicle, epididymis, and deferens), the seminal vesicles, and the prostate (Fig. 16-1).

(1) Penis

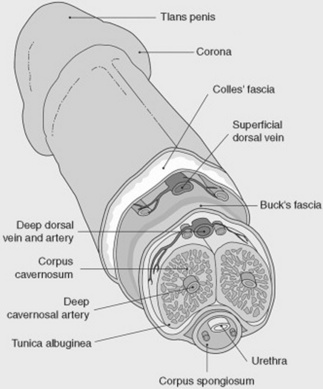

4 Describe the anatomy of the penis.

The penis consists of a shaft, formed by three juxtaposed columns of spongy and vascular tissue: the corpora cavernosa. These can be temporarily filled with blood, thus providing a unique erectile capacity to the organ. The distal tip of the penis consists of a cone-shaped structure called the glans (“acorn” in Latin), which contains the vertical slit-like opening of the urethra (urethral meatus). The glans is separated from the shaft by a circular sulcus called the corona (“crown” in Latin), which in uncircumcised men is covered in a hood-like fashion by the prepuce or foreskin, a fold surgically removed during circumcision. All areas must be examined (see Fig. 16-2).

5 What steps should I take to properly examine the penis?

The first, of course, is precautionary: put on a pair of gloves because some sexually transmitted diseases (including syphilis) can be acquired through simple skin abrasions. With gloves on, examine the penis by first palpating the shaft, and then by carefully looking for areas of induration or tenderness. Then, look for unusual curvatures (see Peyronie’s disease, question 47). Retract the prepuce to gain access to the glans, and inspect it for abnormalities. After completing the exam, return the foreskin to its original position since failure to do so may cause severe edema in unconscious patients. Finally, gently compress the glans between your thumb and forefinger to visualize the urethral meatus, and possibly express secretions. Note that this maneuver may be unyielding even in patients with a history of penile discharge. In this case, milk the shaft of the penis (from its base to the glans), since this may produce a few precious drops for analysis. Finally, examine the base of the penis for hair or skin abnormalities.

9 What is the cause of priapism?

Often idiopathic. Yet, priapism also may reflect systemic or local abnormalities:

Local conditions are usually neoplastic or inflammatory diseases of the shaft, but also thrombotic and/or hemorrhagic processes of the penile vasculature (i.e., arterial high-flow priapism).

Local conditions are usually neoplastic or inflammatory diseases of the shaft, but also thrombotic and/or hemorrhagic processes of the penile vasculature (i.e., arterial high-flow priapism).

Systemic conditions are instead either neurologic lesions (spinal cord injury and spinal anesthesia) or various hematologic disorders that predispose to thrombosis, like leukemia or sickle cell anemia (which are therefore responsible for veno-occlusive priapism). In one study, close to one half of sickle cell patients reported at least one episode of priapism. Finally, the condition also has been reported after recent infection by Mycoplasma pneumoniae, possibly because of secondary hypercoagulability.

Systemic conditions are instead either neurologic lesions (spinal cord injury and spinal anesthesia) or various hematologic disorders that predispose to thrombosis, like leukemia or sickle cell anemia (which are therefore responsible for veno-occlusive priapism). In one study, close to one half of sickle cell patients reported at least one episode of priapism. Finally, the condition also has been reported after recent infection by Mycoplasma pneumoniae, possibly because of secondary hypercoagulability.

10 And what about drugs?

Psychotropics (chlorpromazine, trazodone, and thioridazine, and even serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as citalopram)

Psychotropics (chlorpromazine, trazodone, and thioridazine, and even serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as citalopram)

Anticoagulants (both warfarin and heparin)

Anticoagulants (both warfarin and heparin)

Vasodilators (hydralazine and prazosin, especially in patients with renal failure)

Vasodilators (hydralazine and prazosin, especially in patients with renal failure)

Various others (metoclopramide, omeprazole, hydroxyzine, tamoxifen, testosterone, and androstenedione in athletes)

Various others (metoclopramide, omeprazole, hydroxyzine, tamoxifen, testosterone, and androstenedione in athletes)

“Recreational” drugs such as cocaine, marijuana, ecstasy, and alcohol (which should instead be called destructive drugs, since they kill you, make you destitute, or both)

“Recreational” drugs such as cocaine, marijuana, ecstasy, and alcohol (which should instead be called destructive drugs, since they kill you, make you destitute, or both)

11 What is phimosis?

From the Greek phimos (muzzle or snout), this is a narrowed opening of the prepuce, so that the foreskin cannot be retracted over the glans penis (Fig. 16-3). Usually congenital (from membranes binding the prepuce to the glans), phimosis also may result from acquired adhesions, often the sequela of poor hygiene, previous infections (chronic balanoposthitis), or a too-forceful retraction of a congenital phimosis. If untreated, it can degenerate into squamous intraepithelial cancer of the penis.

13 What is paraphimosis?

A condition related to, but actually different from, a phimosis. Once a phimotic prepuce is forcibly retracted over the glans, the edematous foreskin cannot be brought forward again, thus resulting in paraphimosis, a tight band of retracted foreskin behind the coronal sulcus (see Fig. 16-3). This is a very painful condition, which, if unrelieved, can cause urinary tract obstruction, venous engorgement, edema, and even necrosis of the foreskin and glans.

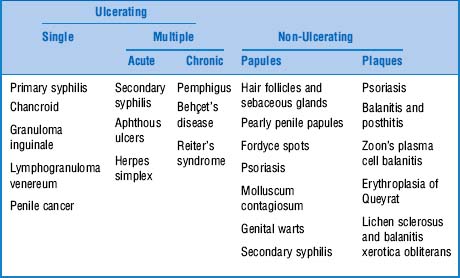

21 What kind of skin lesions can be seen on the penis?

The most common are classified on the basis of appearance (Table 16-1):

24 Describe the ulcerating lesion of chancroid

It is a painful, single ulcer, at times multiple, with lymphadenopathy.

26 Describe the ulcerating lesion of lymphogranuloma venereum

It is a small, nontender ulcer with unilateral tender lymphadenopathy.

34 What are the most important chronic multiple ulcerating lesions?

Pemphigus: These are fragile, thin-walled blisters that eventually break down to form ulcers. Often painful and itchy. Note that pemphigus usually affects other parts of the body (frequently starting in the mouth) but also may involve only the penis.

Pemphigus: These are fragile, thin-walled blisters that eventually break down to form ulcers. Often painful and itchy. Note that pemphigus usually affects other parts of the body (frequently starting in the mouth) but also may involve only the penis.

Behçet’s disease: An inflammatory and noninfectious multisystem disease that involves the skin, joints, nerves, and eyes. Genital lesions present as large, deep, and painful penile/scrotal ulcers, always accompanied by mouth ulcers.

Behçet’s disease: An inflammatory and noninfectious multisystem disease that involves the skin, joints, nerves, and eyes. Genital lesions present as large, deep, and painful penile/scrotal ulcers, always accompanied by mouth ulcers.

36 Describe penile papules. What are the most important lesions of this sort?

Hair follicles and sebaceous glands are completely normal and frequently found on the penile shaft, particularly its ventral surface. Sebaceous glands can be either seen (as small and yellowish nodules, homogenous, and rather symmetrically distributed) or palpated (as small skin lumps). They are often referred to as Fordyce spots (see question 53). Hair follicles, on the other hand, typically contain hair. Neither should be confused with genital warts (which are asymmetric and heterogeneous, with a cauliflower-like presentation) or molluscum contagiosum (which presents as fleshy, rounded, and umbilicated lesions).

Hair follicles and sebaceous glands are completely normal and frequently found on the penile shaft, particularly its ventral surface. Sebaceous glands can be either seen (as small and yellowish nodules, homogenous, and rather symmetrically distributed) or palpated (as small skin lumps). They are often referred to as Fordyce spots (see question 53). Hair follicles, on the other hand, typically contain hair. Neither should be confused with genital warts (which are asymmetric and heterogeneous, with a cauliflower-like presentation) or molluscum contagiosum (which presents as fleshy, rounded, and umbilicated lesions).

Pearly penile papules are multiple, tiny (1–3 mm), pearly appearing, and skin-colored papules around the circumference of the glans’ crown. They typically develop in men ages 20 to 40, with 10% of all subjects being affected, especially if uncircumcised. Although often mistaken for warts (which instead are asymmetric, heterogeneous, and with a cauliflower-like presentation), pearly papules are neither infectious nor symptomatic. Hence, their only “treatment” is reassurance. They are still referred to as preputial or Tyson’s glands, since initially they were believed to be smegma-producing glands.

Pearly penile papules are multiple, tiny (1–3 mm), pearly appearing, and skin-colored papules around the circumference of the glans’ crown. They typically develop in men ages 20 to 40, with 10% of all subjects being affected, especially if uncircumcised. Although often mistaken for warts (which instead are asymmetric, heterogeneous, and with a cauliflower-like presentation), pearly papules are neither infectious nor symptomatic. Hence, their only “treatment” is reassurance. They are still referred to as preputial or Tyson’s glands, since initially they were believed to be smegma-producing glands.

40 And what about genital warts?

These also are quite common, and in fact increasing in prevalence, especially in young and sexually active people. Condylomata acuminata are arbor-like (acuminata) lesions caused by the human papillomavirus virus (the condylomata lata of syphilis are instead flat—see question 41). Usually more wart-like than ulcerating, condylomata acuminata usually occur in moist areas (such as the corona or sulcus), but also may affect the penis’s tip and shaft, plus scrotum, anus, and mouth. They appear as tiny and skin-colored genital warts, isolated or in clusters, and with a shiny surface. These may become fleshy and cauliflower-like. Highly infectious, genital warts can be latent, subclinical, and clinical—very much like herpes. Hence, asymptomatic infection (and shedding) is frequent. The most common agents are low-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) 6 and 11; high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 are less common but are associated with premalignant and malignant degeneration (i.e., squamous cell carcinoma of the penis, anus, and cervix). They may be confused with pearly penile papules.

42 What about penile plaques?

They are usually benign (like psoriasis and Zoon’s plasma cell balanitis) and often infectious (balanitis and posthitis, see questions 15–17). Still, three of these lesions (erythroplasia of Queyrat, lichen sclerosus, and balanitis xerotica obliterans) are quite serious since they may degenerate into penile cancer. Finally, diffuse red plaques with a poorly defined edge and finely scaled surface (eczema-like) may be due to allergic contact dermatitis. Although often the result of lubricants, condoms, spermicides, and feminine deodorant sprays, they are more frequently caused by poor hygiene, with persistent moisture and maceration. They are quite irritating and usually respond to topical steroids.

49 Define hypospadias and epispadias

Hypospadias is a developmental anomaly characterized by a defect on the lower (ventral) surface of the penis. Consequently, the urethral meatus is more proximal than normal, opening on the ventral aspect of the penis rather than on the glans.

Hypospadias is a developmental anomaly characterized by a defect on the lower (ventral) surface of the penis. Consequently, the urethral meatus is more proximal than normal, opening on the ventral aspect of the penis rather than on the glans.

Epispadias is a defect on the upper (dorsal) surface of the penis. Hence, the urethral meatus opens dorsally.

Epispadias is a defect on the upper (dorsal) surface of the penis. Hence, the urethral meatus opens dorsally.

Both these congenital malformations (Fig. 16-4) may lead to fertility problems. They also represent a clue to other underlying abnormalities, such as undescended testis (cryptorchidism), Klinefelter’s syndrome, or other chromosomal disorders. Hypospadias may be induced by the mother’s ingestion of estrogens or progesterone or congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

54 What are the causes of scrotal swelling?

It depends on whether the swelling is bilateral or unilateral:

Bilateral scrotal edema, diffuse and painless, is usually a feature of systemic disease, most commonly anasarca. Ascites, pleural effusion, and scrotal edema are commonly seen in severe congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, or cirrhosis.

Bilateral scrotal edema, diffuse and painless, is usually a feature of systemic disease, most commonly anasarca. Ascites, pleural effusion, and scrotal edema are commonly seen in severe congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, or cirrhosis.

Unilateral scrotal edema, on the other hand, is a sign of local pathology. The most common is a varicocele, from the Latin varix (dilated vein) and Greek kele (tumor).

Unilateral scrotal edema, on the other hand, is a sign of local pathology. The most common is a varicocele, from the Latin varix (dilated vein) and Greek kele (tumor).

55 What is a varicocele?

A condition caused by incompetent valves in the internal spermatic veins, resulting in engorgement along the spermatic cord. Hence, a varicocele resembles a nest of worms, which only presents upon standing and resolves with either a supine position or scrotal elevation. Easily identifiable on exam, a varicocele is quite common, occurring in 15% of the general male population and 40% of men evaluated for infertility. It is, in fact, a common cause of reversible sterility (due to the increased testicular temperature of the affected testis). This was intuited by the first century A.D. Roman physician Celsus, who described the condition as “veins that are swollen and twisted over the testicle, which thus becomes smaller than its fellow inasmuch as its nutrition has become defective.” Note that because of the drainage characteristics of the testicular veins, a varicocele is much more common on the left than on the right. Accordingly, a right varicocele should prompt investigation to exclude either anatomic abnormalities or an alternative diagnosis. Other than a varicocele, localized and painless scrotal swelling usually reflects pathology of the testis or epididymis (see questions 63 and 64). Conversely, painful and tender scrotal swelling usually indicates a much more acute process, such as torsion of the spermatic cord, strangulated inguinal hernia, acute orchitis, or acute epididymitis.

56 What are the normal characteristics of testes and epididymides?

Testes are paired organs, 2–3 cm in thickness, and 3.5–5.5 cm in length. They have the shape of an egg, with the vertical axis being the longest. All but the posterior surfaces are wrapped by a folded serous sheath with a potential cavity: the tunica vaginalis.

Testes are paired organs, 2–3 cm in thickness, and 3.5–5.5 cm in length. They have the shape of an egg, with the vertical axis being the longest. All but the posterior surfaces are wrapped by a folded serous sheath with a potential cavity: the tunica vaginalis.

Epididymides (in Greek, “the ones on top of the testicles”) are two elongated structures attached to the posterior surface of the testes (even though in 7–10% of normal adults the epididymides are located anteriorly to the testicles). Each structure consists of a head (caput epididymidis), body (corpus epididymidis), and tail (cauda epididymidis). The tail turns sharply upon itself to become the ductus (or vas) deferens. Both the tail and the beginning of the ductus deferens serve as reservoir for spermatozoa. Secretions from the ductus deferens, seminal vesicles, and prostate form the semen.

Epididymides (in Greek, “the ones on top of the testicles”) are two elongated structures attached to the posterior surface of the testes (even though in 7–10% of normal adults the epididymides are located anteriorly to the testicles). Each structure consists of a head (caput epididymidis), body (corpus epididymidis), and tail (cauda epididymidis). The tail turns sharply upon itself to become the ductus (or vas) deferens. Both the tail and the beginning of the ductus deferens serve as reservoir for spermatozoa. Secretions from the ductus deferens, seminal vesicles, and prostate form the semen.

57 How should the testes and epididymides be examined?

With great care, since these organs (especially the testes) are exquisitely sensitive, not only to touch but also to temperature. In fact, in a cold room they may even retract toward the inguinal canal. Hence, to best palpate them, use your thumb plus index finger, or thumb plus index and medium fingers. This also allows you to gauge the length and thickness of each testicle, although for more accurate measurements, you will need a caliper. Note any discrepancy in consistency or size, and, if present, ask how long this has been so. If ruling out a congenitally undescended testis, examine the inguinal canal for localized swelling. Search for testicular lumps or bumps, which, if present, should be considered neoplastic until proven otherwise. Still, keep in mind that diffuse testicular enlargement usually reflects either a hydrocele (see question 59) or a varicocele (previously discussed, see question 55). Note that the left testis lies a bit lower in the scrotum than its counterpart (the reverse would suggests situs inversus). Also note that, although the testicles can be examined in either the standing or supine position, a search for hernias or varicoceles requires the patient to stand. Finally, move cephalad and gently assess the upper and posterior poles of the testes and adjacent heads of the epididymides. Examine the spermatic cord, which goes from the epididymis all the way up into the inguinal canal. This contains the vas deferens, the testicular artery/vein, the ilioinguinal nerve, plus lymphatic vessels and fat tissue. Of all these structures, only the vas can be easily recognized, based on its firm and wire-like feel and the location along the posterior aspect of the bundle. Identify any lumps or bumps in the cord, and then note their relationship to the testes and inguinal canal. Note that a varicocele will be palpable not only in the testes, but also throughout the length of the cord, since it represents a varicose dilation of the spermatic vein.

B. Hernia Examination

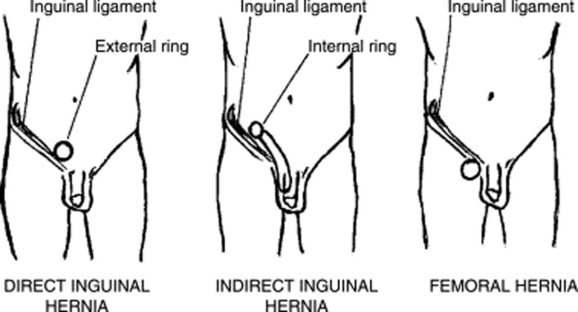

65 What are the two possible sites of groin hernias?

Inguinal hernias: More common than femoral hernias and the most frequent of all abdominal hernias. They may occur medially (direct hernias) or laterally (indirect hernias). Both present as a bulge in the inguinal crease. Indirect hernias are the most frequent, affecting patients of both sexes and all ages, although typically more common in children. They originate above the inguinal ligament (near its midpoint [i.e., the internal inguinal ring]) and are due to a defect in the abdominal ring, through which the spermatic cord exits the scrotum and enters the pelvis. Hence, they follow the testicular embryologic pathway, descending from the abdomen into the scrotum. Direct hernias also originate above the inguinal ligament, but in a congenital defect near the external inguinal ring and pubis tubercle. They usually affect men 40 years of age or older (since the abdominal wall weakens with age), rarely progress into the scrotum, and on examination bulge anteriorly, pushing the side of the finger forward.

Inguinal hernias: More common than femoral hernias and the most frequent of all abdominal hernias. They may occur medially (direct hernias) or laterally (indirect hernias). Both present as a bulge in the inguinal crease. Indirect hernias are the most frequent, affecting patients of both sexes and all ages, although typically more common in children. They originate above the inguinal ligament (near its midpoint [i.e., the internal inguinal ring]) and are due to a defect in the abdominal ring, through which the spermatic cord exits the scrotum and enters the pelvis. Hence, they follow the testicular embryologic pathway, descending from the abdomen into the scrotum. Direct hernias also originate above the inguinal ligament, but in a congenital defect near the external inguinal ring and pubis tubercle. They usually affect men 40 years of age or older (since the abdominal wall weakens with age), rarely progress into the scrotum, and on examination bulge anteriorly, pushing the side of the finger forward.

Femoral hernias are less common, especially in males. They originate below the inguinal ligament and are located laterally to the site of inguinal hernias. They often are confused with femoral lymph nodes. They do not progress into the scrotum and on examination are associated with an empty inguinal canal (Fig. 16-5).

Femoral hernias are less common, especially in males. They originate below the inguinal ligament and are located laterally to the site of inguinal hernias. They often are confused with femoral lymph nodes. They do not progress into the scrotum and on examination are associated with an empty inguinal canal (Fig. 16-5).

66 What is the best way to detect a hernia?

Start with inspection. Ask the patient to stand while you comfortably sit in a chair. Observe the external inguinal ring, looking for a localized bulge. If not visible, elicit the bulge by asking the patient to either cough or perform a Valsalva maneuver. After inspection, palpate the patient’s right inguinal region with your right index finger and the patient’s left inguinal region with your left index finger. Gently insert the finger along the spermatic cord, through the invaginated scrotum (Fig. 16-6), aiming for the external ring of the inguinal canal (from where the cord emerges). As your fingertip reaches into the external ring, put the fingers of your opposite hand over the inguinal canal, or over any noticeably swollen area. Ask the patient to cough or strain and see whether you can feel, with either hand, any bulging/impulse suggestive of hernia.

A strong palpable impulse that pushes your finger out argues for a direct inguinal hernia

A strong palpable impulse that pushes your finger out argues for a direct inguinal hernia

A soft impulse without any bulging suggests instead an indirect inguinal hernia, gently descending the inguinal canal

A soft impulse without any bulging suggests instead an indirect inguinal hernia, gently descending the inguinal canal

Finally, an empty inguinal canal argues for a femoral hernia. This can be substantiated by placing the index and middle fingers into the triangle lying medially to the femoral artery. A palpable bulge in this area after straining or coughing confirms a femoral hernia.

Finally, an empty inguinal canal argues for a femoral hernia. This can be substantiated by placing the index and middle fingers into the triangle lying medially to the femoral artery. A palpable bulge in this area after straining or coughing confirms a femoral hernia.

68 Should one auscultate over a hernia?

Yes, since presence of bowel sounds would confirm bowel herniation.

C. Digital Rectal Examination (DRE)

82 What does the normal prostate look like?

It has the shape of a heart (which makes it especially endearing to those of us who are romantically inclined) and the size of a walnut. Enlargement does not necessarily indicate cancer but is instead a common sign of benign prostatic hypertrophy—a frequent by-product of aging. Nodules, on the other hand, are invariably suspicious and thus should always be biopsied. Still, only 50% of all nodules eventually turn out to be neoplastic, with the rest usually reflecting benign prostatic hypertrophy (hence, the low positive predictive value for cancer—see questions 83 and 84). Also, a localized area of induration is not necessarily typical of early cancer, but more of a late neoplastic process.

1 Akhtar AJ, Moran D, Ganeson K, et al. Safety and efficacy of digital rectal examination in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1463-1465.

2 Buechner SA. Common skin disorders of the penis. BJU Int. 2002;90:498-506.

3 DeGowin RL. DeGowin and DeGowin’s Bedside Diagnostic Examination, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

4 Edwards S. Balanitis and balanoposthitis: A review. Genitourin Med. 1996;72:155-159.

5 Gairdner D. The fate of the foreskin: A study of circumcision. BMJ. 1949;2:1433-1437.

6 Gerber GS. Carcinoma in situ of the penis. J Urol. 1994;151:829-833.

7 Guinan P, Bush I, Ray, V, et al. The accuracy of the rectal examination in the diagnosis of prostatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:499-583.

8 Hennigan TW, Franks PJ, Hocken DB, Allen-Mersh TG. Rectal examination in general practice. BMJ. 1990;301:478-480.

9 Hoogendam A, Buntinx F, de Vet HC. The diagnostic value of digital rectal examination in primary care screening for prostate cancer: A meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 1999;16:621-626.

10 Imamura E. Phimosis of infants and young children in Japan. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1997;39:403-405.

11 Oster J. Further fate of the foreskin: Incidence of preputial adhesions, phimosis, and smegma among Danish schoolboys. Arch Dis Child. 1968;43:200-203.

12 Sapira JD. The Art and Science of Bedside Diagnosis. Baltimore: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1990.

13 Singhal VK, Razdan JL, Gupta, SN, et al. Carcinoma of the penis. J Ind Med Assoc. 1991;89:120-123.

14 Willms JL, Schneidermann H, Algranati PS. Physical Diagnosis. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1994.